Welcome all, to another thrilling installment of A Song of Pins and Needles! As promised in my last piece — written in 2017 — I am producing this article “sometime after season seven ends.” I am delivering on my very explicit promise!

We start our adventure with Sansa Stark, looking back at costumes from season 6-8. Check out the first Sansa Stark piece if you haven’t already. Since Sansa goes through several iterations of personalities throughout these seasons — which you can read about in the Book Snob glossary — I will be just referring to her as Sansa, and differentiating for when we discuss the books. Also, recall a few important definitions:

Watsonian: how a fact or design works within the confines of the story; and

Doylist: the real-world explanation for a fact or design within the story.

“D&D” refers to the entire Game of Thrones production team, while “Clapton & Co.” refers specifically to the costume designers. And remember that if a dress is pretty, I am likely to forgive more of its sins. Likely.

A Seemingly Innocuous Piece in the Pattern (pun fully intended)

We jump off with a look at Sansa’s season 6 green (black?) velvet dress, which she wears throughout the season. The dress itself is basic, and I actually like a lot of the components, though the final product is blech. Velvet is a lovely fabric, and does make Watsonian sense (it can be warm), and it would likely be available from the ships that trade with Eastwatch and the North generally. The embroidery, too, makes sense — Sansa made her own dress, and she’s going to put her own house sigil on it, especially given the harrowing experience she recently had with House Bolton. So it survives Watsonian analysis, neat! Then why do we care? Do we need to move on to Doylist analysis if the garment makes sense in-verse? Indeed we do, to an extent. I question the velvet dress’s Doylist motives not because there’s anything wrong with this dress itself, but rather because it is a piece in a pattern. Recall Sansa’s Empowered ™ warlock costume:

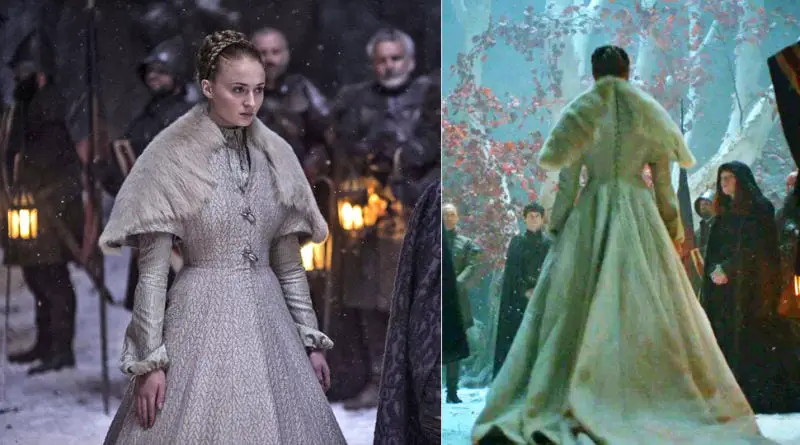

And a few additional similar black dresses that appeared in season five. Now compare those to her wedding dress:

Notice a difference? We’ve already explored how Sansa’s wedding dress is white and virginal, and part of that is that she is covered up to her neck — even while other ladies at the wedding bared their cleavage. Every dress since Sansa’s wedding follows this pattern: buttoned-up to her neck. The velvet dress is part of that pattern. So what does it mean?

It is possible to interpret this costume change as a choice by Sansa the character in reaction to being “exposed” by Ramsey’s sexual abuse. Indeed, this is a nuanced change, where a clothing decision — something Sansa Stark is hyper aware of — does, in fact, reflect a change in the character. I think this is a fair interpretation on its own.

But continuing to explore the pattern reveals some unfortunate implications and, at the end, undermines that subtle reading of the material.

Virginity Belts and Other Poor Metaphors

The first hint I got that something strange was going on with Sansa’s costumes came during season 7, with this black dress with a belt:

Doylist-wise, it’s a perfectly fine dress. And Michele Clapton spoke multiple coherent words about it, actually, where she explained that the pattern on the dress reminded her of fish, which is of course Sansa’s mother’s house sigil. Now that is using design elements in a unique way! Unfortunately, Clapton & Co. went on with one of their notorious word-salads to explain more details that, as per usual, did not need explanation:

“With one of the key pieces this year, I wanted it to look as if she was actually sewn or laced into her dress—like there was no way in. So I designed a belt that comes around the neck, across the chest and around the waist. She’s trying to protect herself from all the awfulness that’s happened. It’s a form of armor. It will be interesting to see how that moves forward.” — Michele Clapton

“She is almost [inaccessible] to anyone; she’s almost strapped down. It’s this idea of being wrapped and unavailable and not feminine. It’s sort of halfway, not masculine and not feminine, it’s just Sansa,” says Clapton.

Let me take a moment to explain why I care about these explanations. I’m not just being nitpicky (I swear!) — the fact is, these costumes don’t need an additional explanation besides “it’s cold and so the character is wearing a dress with a belt and a cloak”. Clothing and design need not always be significant; and indeed, if you try to make EVERYTHING significant, then really nothing is significant. That said, if you decide to imbue something with additional meaning — a dress, a hair style, a piece of jewelry, a house sigil — then you must think through the implications of that meaning. If your intended meaning reveals inherent problems (ie, sexism), it is perfectly fair for an audience to criticize it, and to be concerned.

By way of example, consider the house sigils in A Song of Ice and Fire. Some of them are just sigils that generally don’t come into play in any meaningful way. Some of them do — the Targaryen dragon having three heads is a device the characters discuss in-verse in relation to dragons, and has quite an influence on Daenerys. But there are other ones that are more subtle: the Frey sigil, for instance, is a literal double crossing.

And so that sigil is a literary device, used as part of the foreshadowing for the Red Wedding. Naming a chapter The Princess in the Tower is a direct critique of the usual trapped princess trope, and speaks directly to the readers (I mean, Martin my as well have been looking directly at the camera when he wrote that one). These details are interesting and add value to the text as a literary piece. There is nothing innately wrong with trying to mimic the same significance in a visual adaptation.

That said, when you do try to imbue something with additional significance, and you mess it up royally, then it calls into question the Watsonian purpose behind the design. Analyzing these extraneous, unnecessary details can shine a light on bigger problems (read: sexism), and give us another avenue to understand issues with a piece of media. Additionally, as humans depend largely on visuals, it is important to understand what we are seeing and why we are seeing it.

So strap yourselves in — just like Sansa! — and get ready to take this quote one line at a time.

“I wanted it to look as if she was actually sewn or laced into her dress—like there was no way in.”

Alright, at the outset, it isn’t totally stupid to think that Sansa — a survivor of violent sexual trauma — may not want to appear sexy or sensual. It is reasonable that someone may react to such a trauma by avoiding the appearance of sexuality all together, as their experience with sex was violent and forced. That’s an explanation for this design that I can get behind.

Note that this is not the explanation we are given! It takes a bit of piecing together to get the whole picture, so bare with me, my darling friends.

The idea of Sansa being “sewn” or “laced” into her dress as if “there was no way in” begins to substantiate the acceptable explanation of the costume: in that she wants to keep people out. Note, though, that on the flip side, this also means Sansa is trapped in the garment. Perhaps deep and meaningful? I’ll leave that to you.

It took me all of 30 seconds of thought to realize, though, that no matter how “sewn” or “laced” in Sansa is, that form of “protection” wouldn’t have stopped her sexual abuse. If you recall the rape scene in Unbowed, Unbent, Unbroken, Ramsey specifically rips Sansa out of her wedding dress — we see him grabbing at the back and we hear the ripping noises. It’s not like he was bamboozled by all those buttons.

Indeed, any dress or skirt could be kept on while a sexual assault is occurring. So in practicality — if there is a practical concern here at all — Sansa’s strappy belt does nothing to protect her. Which makes the next part of the explanation moot:

“She’s trying to protect herself from all the awfulness that’s happened. It’s a form of armor. It will be interesting to see how that moves forward.”

Much like the needle necklace, that is in fact not a weapon, this strappy belt is in fact not a form of armor and offers literally no protection. Does it offer metaphorical protection? Is it symbolic, at least? If we look to more details provided by Clapton & Co., the true nature of the design begins to reveal itself:

“She is almost [inaccessible] to anyone; she’s almost strapped down. It’s this idea of being wrapped and unavailable and not feminine. It’s sort of halfway, not masculine and not feminine, it’s just Sansa,”

And again, per their own words, the D&D gang betray their actual motivation: sexism.

Note the words Clapton & Co. use as synonyms: strapped down, wrapped, unavailable, and not feminine. The costume is recognizing that Sansa Stark is now no longer feminine because she is covered and unavailable, directly linking her sexual availability to her womanhood. My dudes, this is sexism 101; this is as bad as reducing Catelyn Stark to Motherhood, or Loras Tyrell to a Gay. Sansa is now Not Like Other Girls because she has zero sexuality.

But wait — don’t we want Sansa to stop being objectified? Aren’t we glad she isn’t a sexual object? Don’t we hate her hymen being traded around like a baseball card?? The answer is YES, yes we do hate all of that. But there is a difference between a female character gaining agency which she uses to control her sexual destiny, and a female character being written as “empowered” and therefore, as a foregone conclusion, not having any sexual desire. It’s as if Sansa has gone to the opposite end of the spectrum as Margeary in previous seasons. While Marg was the scheming sexual manipulator, only present on our screens to be sexy and use her sexiness to be Empowered ™, Sansa is now stripped of any sexual agency so she doesn’t have weak “feminine” qualities and is now, too, Empowered ™. In neither situation does either character actually have agency, and neither situation is good female representation. It is just two different ends of the same sexism spectrum.

And don’t get me started on Sansa not being “masculine or feminine”; my heart weeps for Alayne.

It’s a Statement!

The armor was made of leather rather than metal, but that was by design. Clapton told me, “It’s not about protection, it’s a statement! Sansa’s armor is a direct reaction to Dany’s assertion of power.” — Michele Clapton

I am not going to spend anymore time on the needle necklace bullshittery, as that analysis remains consistent. Instead, let’s consider this outfit based on how Clapton explains it.

Say nice things: I don’t hate this idea. Sansa Stark making a statement with a garment is reasonable in a Doylist way. And I actually find this armor piece quite beautiful and visually interesting, which is of course a key component in all costume design. So I think this one survives most critique.

It did make me recall Cersei’s armor corsets back in the earlier seasons, which I greatly disparaged at the time. For me, the different is in the presentation: Cersei’s corsets are gaudy, ugly, and fit the trope of “boob armor”, while Sansa’s leather breastplate is more akin to real armor. The purpose of Sansa’s isn’t to accentuate her femininity and literally outline her boobs in metal — so why the difference in “armor” styles between the characters?

I think part of this difference comes down to an understanding of how “feminine” Cersei was in the earlier seasons versus the perceived lack of femininity about Sansa in season eight; and all the negative connotations from that are present with due force. The other part, it seems, is simply Michele Clapton’s taste. Clapton expressed before that Sansa’s style is most akin to her own, even wearing the needle necklace in her daily life, and is one of the reasons she loves designing for Sansa. This could explain the seemingly anachronistic (for lack of a better term) aspects of Sansa’s outfits — the turn to black sooner than others, the variety of necklines, the use of leather, chains, furs — that amount to a look that is at times out-of-place.

Sansa’s season eight armor suffers from that problem; I like it, my eyes like it, and my Doylist senses are mostly satisfied, but it looks oddly futuristic. Though I will not begrudge Clapton for designing something to her taste. As an anecdote, I tend to design or select costumes that are only 2 colors (sometimes 3), and basically have no ability to design outside of that. That’s just what my brain likes — so you can be sure if a costume exists that is one or two colors, I’ll be in it at some point!

Which brings me to my next question: why is everything black?

Where’s the Color Gone?

Fortunately Clapton & Co. have finally solved this mystery for us. Spoiler alert: it starts with an S and ends in an EXISM!

“People say ‘Where’s the color gone?’ Well, there is color in there, but it’s very subdued. If the end of the world was coming as you know it, you wouldn’t actually be colorful and bright. You’d start being incredibly practical. And, actually, you’d be hiding your femininity. I think that’s really important. I wanted the strength in them.” — Michele Clapton

I’m on board with the idea that clothing choice is a form of expression, and that one may not feel like wearing “colorful and bright” clothing during an apocalyptic event; that’s fine. I’m more sold on the idea that fashion goes by the wayside in favor of practicality, especially in a cold northern climate where proper warm clothing literally makes the different between life and death.

You all know my problem with this quote comes at the mention of femininity. Clapton & Co. assert that, in an apocalyptic time, a woman would be “hiding” her femininity. Why? Because femininity is weak. As she says, “I wanted the strength in them.” In order order to be Strong ™, Sansa and the other female characters had to hide their femininity, because only masculinity is appropriate in the apocalypse. And consider that Sansa — only after successfully hiding her femininity — is rewarded by the narrative with queenship in the north; the only female character in power at the end of the series.

The horrible implications are apparent. I’ll expand on it only to this extent: taking the character of Sansa Stark, whose entire book story arch is about finding strength by achieving agency using her social standing- courtesy is a lady’s armor, and recall, her skin turned from porcelain to ivory to steel- a social standing that not only includes but is reliant upon her position as a woman, as the oldest daughter of a noble house, and instead having her “hide” her femininity so that she can be “strong”, reveals not only a complete lack of understanding of the source material, but also an inability to understand complex social situations. Simplifying this character in this way reveals that D&D’s mindset is extremely narrow, simple, and all-around basic.

I say D&D’s, and not Clapton & Co.’s, because the problem goes well beyond the costume design. These issues permeate from the bad writing, as we’ve discovered in articles past. I don’t think it is fair to rest these massive sexist laurels on Clapton & Co., as it is obviously a problem of the show creators.

In a steel-manning defense, in a better show, this could be reflective of Sansa realizing she needs to hide her femininity to be strong or taken seriously by the men around her. However, none of that groundwork is laid, the source material tends to contradict that idea, and the pattern of writing pretty much puts the kabash on that one. Don’t say I didn’t try to make it work.

Queen of the North! …and south…?

Our last look at Sansa concerns her Queen of the North coronation gown, which appears on our screens for maybe like 17 seconds in the finale of Game of Thrones. Let me start with the positive: gosh this is so pretty!!! This is the first costume I’ve seen in a lonnggg time that I would actually spend the time replicating. And, to her credit, Clapton included a lot of details that make solid Watsonian and Doylist sense; and for once, the slip-ups that do occur are not, I believe, sexist in nature. But we’ll get there.

Luckily we don’t have to do much digging to know what the dress was supposed to represent. Michele Clapton explained the biggest things in an Instagram post, and the other things are relatively obvious, as discussed by others before me. Let’s start with the good things:

- Color! The color of the dress is grey. This is a Stark house color. Good job! Yay! And whether it was intentional or just lucky coincidence, Sophie Turner wearing light grey with her red hair is indeed evocative of the weirwood tree, recalling a powerful part of northern mysticism, which makes the look all the more striking. In addition, the grey tones of the gown highlight her red hair, which is a distinctly Tully trait: the beauty of this color combination is that it both reinforces northern identity while also merging Sansa’s Tully identity. It’s like a theme!

- Embroidery! Yay! Both major pieces of embroidery on the dress are great. The first is the direwolf head on Sansa’s left shoulder. This is (a) literally the symbol of House Stark, and (b) the “feminine” version of wearing an actual wolf skin, which we’ve seen in the show before. I say “feminine” because it required a high-level skill of sewing — as opposed to hunting — to create this direwolf head, and sewing is a “traditionally feminine” activity in Westeros (and Weisserof). The second piece of embroidery are the weirwood leaves on the inside of Sansa’s right sleeve, which again are evocative of northern mysticism while looking badass as hell.

3. Metal bodice — Clapton told us specifically that this is designed to look like the branches of weirwood trees. Yes! Fantastic! It’s clearly a bodice (it ties on), which makes more sense for Sansa than “armor”, and it does not suffer from boob armor problems. It is beautifully crafted, fits great, and looks striking. And the call to the weirwoods is appropriate from all angles.

See, I can like stuff! And overall I do like this costume. But I wouldn’t be me if I didn’t have complaints; and Clapton wouldn’t be our girl Clapton if she didn’t have some weirdo ideas that she expressed in her classic word-salads.

“The dress was made in the same fabric as the dark Sansa dress, which was the same fabric dyed that was used in Margaey’s wedding dress to Joffrey. Sansa had a bond with her. It has falling leaves as its pattern.” — Michele Clapton

I’m sorry, come again? Sansa had a bond with Margeary? Please cite your sources before you come at me with your weird honeypots. Sansa and Margeary in the show had no such bond — in fact it’s pretty clearly implied that the Tyrells were trying to use her to get the North — and they definitely were doing that in the books. Unless the bond Clapton is referring to is the queer baiting scene, I don’t know where she got this from.

And even if they did have a bond, Sansa Stark is going to pay respect to her dead friend with whom she had this great bond, her friend who literally got blown up, by… using the same fabric in another dress? What? And a fabric that doesn’t even contain the sigil of the demolished house that her greatly bonded friend belonged to? Or the colors?? I don’t understand???

“The pattern is of falling leaves.” Okay, and?? Stating facts doesn’t make it a metaphor. At least on Marg it made a little sense, since her house sigil is a plant, and plants have… leaves. How does this fit into the Queen of the North’s coronation gown? It’s not like they’re falling weirwood leaves, which Clapton & Co. managed to EMBROIDER on the SAME DRESS literally ONTO THE FABRIC that we’re discussing. Do Clapton & Co. have any understanding of what symbolism actually is?

Not to beat a dead horse, but this doesn’t make Watsonian sense for a much simpler reason: where the hell did Sansa get this fabric? Like, legit, Marg’s wedding dress must’ve been made in King’s Landing. Literally four-ish years before this gown. The metacademy of the arts isn’t that good, folks.

Additionally, I’m bothered by the feathers on this dress. Not that it couldn’t possibly have meaning — she is the “little bird” after all — but more because it’s just too much. The costume needs a little editing; sometimes there are too many ideas happening. This same complain applies to the chain, which is barely visible, but is her infamous needle-necklace. Seven save us all.

Last, we need to talk about this crown. We know from the text that the ancient Kings of Winter, who ruled in Winterfell before Aegon’s conquest, wore hammered bronze sword crowns, as depicted here.

It’s obvious that the show’s design is not the crown of winter. This is disappointing, because it would’ve been totally badass and actually empowering to see Sansa wear a truly northern crown. It is curious — given that we have a direct description of the crown worn by northern rulers in the text — that it would be completely ignored. Though I wouldn’t say I’m surprised.

Clapton & Co. did not directly comment on the inspiration of the crown design, though others have pointed out its obvious symbolism with the two direwolves. There is also the blatant similarity to Cersei’s lion crown. It’s the latter design that gives me pause.

We’ve been told by the script that Sansa learned a lot from Cersei, and we’ve been told by D&D in various interviews. It is an understood aspect of show!Sansa’s character that she learned from Cersei — and what she learned was to be more manipulative, ruthless, and Empowered ™. This is in direct contradiction to book Sansa, who feels the exact opposite about ruling as Cersei does: when Cersei instructs Sansa to rule with fear, Sansa — a 13-year-old girl — immediately thinks: “When I am queen, I will make them love me.” (CITE BOOK).

This is a deliberate contrast made in the text to differentiate these characters. If anything, book Sansa learns from Cersei how not to rule. Consequently, the idea that Sansa would incorporate any decoration into her own presentation as Queen in the North — especially something as significant as a crown — that at all reflects Cersei Lannister is preposterous. And it’s missing the point. Again.

Honestly, I don’t know if Sansa mimicking her crown after Cersei’s crown is sexist — it feels like it has a sexist undertone, in that there is one way to be a stock Empowered Woman ™, but it isn’t clear. I leave that bit to you, dear reader.

Sansa’s Costumes as part of the “Pattern”

I think it is important to consider, now at the end of this terrible journey that was Game of Thrones, why costuming is a vital piece to analyze in a visual medium with each character. Sansa Stark is a good place to start because the pattern with her treatment is relatively obvious: masculinity is strong, femininity is weak. And all the bad implications therein.

I mentioned in the beginning that Sansa’s velvet dress is not independently offensive, nor does it break a doylist lens. However, it is part of a pattern of costuming Sansa throughout the series to code her as certain tropes: the “innocent” or “naive” girl in the beginning, who wears pastels and pinks and flowers; the “feminine” and “powerless” and “weak” woman in King’s landing, wearing clothing that mostly covered her (especially in contrast to Margeary), with slightly darker purple gowns; the “dark” and “sexy” Darth Sansa, who is now “empowered” and “strong” as she becomes “a true player in the game of thrones” with her plunging necklines; the sudden turn to “virginal” and “pure” in her white wedding dress buttoned up to her neck; and the subsequent covering of Sansa’s entire body for the remainder of the series as she becomes “strong” and “not feminine” and “unavailable”.

The coding with Sansa could not be clearer: feminine things are weak, masculine things are strong. And more to the point, sexuality is linked with strength on both extremes — when she is feminine, Sansa gains strength from being hyper-sexual; when she is masculine, Sansa gains strength from being non-sexual. It is a fascinating dichotomy that is visually qualified by the costume design. And it is a dichotomy that is concerning.

The crux of the issue is that these iterations of Sansa Stark are based on gendered stereotypes, and not on the complex character in the source material. It is a stereotype that femininity is weak — in fact, it is a sexist opinion. It is a stereotype that women use sex to manipulate men. It is a stereotype that women who cover their bodies are prudes or virginal, while women who do not are sexually available. These are all sexist ideas that, within the confines of the television show, undergo zero critique or analysis. In the books, Sansa Stark is able to use these stereotypes to her own benefit as she truly does learn how to play the social-political game in Westeros. Her ability to tease out agency within this restrictive system is the commentary on the feudal order and the importance of women in the world. The show, by contrast, simply plays the stereotypes straight. It is this straight-forward application of sexist stereotypes to Sansa’s character and design that rob her entirely of her character arch, undermine the purpose of the source material, and, frankly, reveal that D&D are intellectually unable to understand these complex ideas.

And so I bitch about costumes because the visuals are a huge part of their storytelling, and their storytelling needs to be understood as fundamentally flawed.

Conclusion

In sum, Sansa’s costumes for the series have had serious ups and downs, but consistently betray the creator’s misunderstanding of the source material, in both their conception of the world and of Sansa Stark.

Next on tap will be our girl, Daenerys Stormborn. Join me “soon” for another installment of A Song of Pins and Needles.

P.S. I suggest that everyone who enjoys Unabashed Book Snobbery also listen to Postgame of Thrones, which is another book snob podcast I discovered after season 8 (unfortunately). If you like UBS you will also like PGOT! (But disregard their incorrect opinions on my boy Davos Seaworth)