Content warning: discussions of domestic violence and sexual assault; (mild) Spoiler warning for Cats (2019)

A Quick Summary:

While Demeter was originally the focus of my pitch, no analysis of her would be complete without addressing her best friend, Bombalurina. They’re a packaged set. Yesterday, I detailed Demeter’s history as an abuse survivor and how it shaped her character as we see in the theatre production. Macavity, the story’s antagonist, was abusive to her, going so far as to rape her. In the show, he appears partially to kidnap her as he still desires to dominate her. Demeter sings ‘Macavity: the Mystery Cat’ with Bombalurina, her best friend. Their dynamic in the song and within the greater production reveal the duality within the latter cat, because though Bombalurina appears to be a shallow and sexual trope, she refuses to be pinned down like that. This article will address her character, the necessity of her friendship with Demeter, and its feminist implications, especially when contrasted against certain cinematic decisions evident in the marketing. As I did in yesterday’s article, two of my sources will be the Omnibus documentary on Cats choreographer Gillian Lynne and Dr. Dorothy Dodge Robbin’s article on T.S. Eliot’s cat names. For further reference, in 1981 Sharon Lee-Hill and Geraldine Gardner originated Demeter and Bombalurina respectively.

Bombalurina’s Relationship to Life:

In terms of animal archetypes, if Demeter falls more alongside the nurturing mother figure, then Bombalurina comes from the sexually liberated, independent woman, one seen as having no ties to society. Bombalurina diverges from this archetype, her friendship with Demeter the best evidence for her complexity. Her treatment of Demeter speaks volumes. So often archetypes of sexualized women; like the witch, man-eater, and femme fatale; are portrayed as solitary, disavowed from social connections. Or depictions of friendships with other women are toxic. Bombalurina is the protector, the big sister. Her intense sexuality and independence are rooted in a general intensity and passion for life, which she directs just as much into her non-romantic relationships.

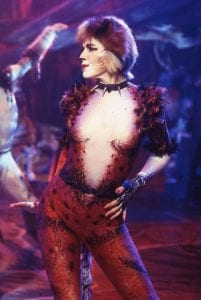

She is always portrayed as having red fur, and casting typically calls for a tall, supple woman. She wears gloves similar to Demeter. Hers though only connote elegance rather than elegance and armor, as Bombalurina was able to move past her trauma and never internalized it the way that Demeter did. In Omnibus, Lynne discussed the women’s friendship and mentioned them as “hav[ing] known intimately the same dangerous man,” implying that Bombalurina had also been involved with Macavity (t. 12:54-12:59). Their old character page on the musical’s website also states that they “both share a stirring hatred towards Macavity[.]” Bombalurina likely endured a level of domestic violence, just not at the level that Demeter had.

She is always portrayed as having red fur, and casting typically calls for a tall, supple woman. She wears gloves similar to Demeter. Hers though only connote elegance rather than elegance and armor, as Bombalurina was able to move past her trauma and never internalized it the way that Demeter did. In Omnibus, Lynne discussed the women’s friendship and mentioned them as “hav[ing] known intimately the same dangerous man,” implying that Bombalurina had also been involved with Macavity (t. 12:54-12:59). Their old character page on the musical’s website also states that they “both share a stirring hatred towards Macavity[.]” Bombalurina likely endured a level of domestic violence, just not at the level that Demeter had.

So often Bombalurina is presented as the slinky, flirty queen in articles, something I noticed as I read the news on the upcoming film. This assessment isn’t wrong, but it’s not wholly accurate either. Similar to Demeter, information from actors and official organizations affirm general fan interpretations about her character, revealing the layers. In this case, Bombalurina’s good-hearted nature. Little Acorn Productions listed Bombalurina’s character description as “generous, confident, [and] frank”, before elaborating that she’s also “kind and touching.” (The latter information came directly from her character page.) For its audition instructions, the Xclaim! theatre company summarized her as “protective and loyal.”

BirminghamLive interviewed actress Charlene Ford in 2014 about Cats, revealing similar characterizations: “When Charlene took on Bombalurina, she was given three character words to work on – generous, voluptuous and frank. […] “I like to think of her as a sassy cat,” says Charlene. “She’s flirtatious and laid-back, nothing really fazes her.”” Then in 2016, Christine Cornish Smith debuted as Bombalurina on Broadway. She raved about the character, as well as provided information on Bombalurina’s psychology:

[Bombalurina] is generous, sexy, authentic. She can be a bit wild and out there, and almost fell into a rough and hard life, but when it comes down to it, she is there for her tribe and knows when to step up in order to protect her family. She is also just no-nonsense. I think that’s what I love about her the most. I strive more and more in my own life to strip away the excess and get down to the truth and delving into a character like this almost helps me notice chances to be very honest in my own life.

Fans had speculated that Demeter and Bombalurina encountered the criminal underworld through Macavity, possibly being members of his gang. As far as I could find, this tidbit about Bombalurina’s past — the near fall from grace — has never appeared elsewhere. (It’s also refreshing that a fun-loving character can also be no-nonsense, because fun and responsibility are not mutually exclusive, even though pop culture would have us think differently.) This backstory also partially explains Bombalurina’s initial hostility to Grizabella, the latter the embodiment of Bombalurina’s fears about the future and possible failings.

Several years ago, writer Kaci Diane posted, “I love the person I’ve become, because I fought to become her.” That captures Bombalurina and her self-actualization to me, and her harmonious contradictions begin with her name. In her article on Eliot and names, Robbins analyzed “Bombalurina”, noting,

Eliot’s second category involves the selection of a “name that’s particular” […] to each cat, one he further characterizes as possessing the oppositional qualities of peculiarity and dignity. […] Bombalurina combines bomb with ballerina, certainly oppositional images that inspire readers to imagine a once lithe feline grown weighty or perhaps a cat that is balletic despite its girth. (p. 24)

Eliot’s text came without any visual reference, so I can’t say what I would picture if I hadn’t been influenced by Cats. But I know that when I hear “Bombalurina” I picture an elegant explosion (fireworks included), reinforced by her svelte, scarlet design. Since the 1930s, the term “bombshell” as a term for an attractive woman has also become more popular. With her name conjuring imagery of fire, Bombalurina’s character contrasts and compliments Demeter’s even more, as her element fits alongside Demeter’s earth-associations, which I will discuss in a bit.

When it comes to adapting Cats, whether for another stage production or for the cinema, Demeter and Bombalurina have been designed as necessary foils and friends. To authentically interpret one of their characters requires the other. We see Demeter in vulnerability, since she leans on Bombalurina the most. Thus we see Bombalurina offer compassion to another woman, contrasted against her aggressive feelings toward Grizabella. As Demeter sings “Grizabella the Glamour Cat”, Bombalurina walks over and puts her arm over Demeter’s shoulder, joining in the singing. But she does so with restrained anger and distrust. Contradictions, complications, and cats.

Bombalurina checks in with Demeter throughout the play, as evident by shots of the actresses’ interactions in background shots. In the 1998 film, when the disguised Macavity enters the Junkyard, the camera zooms in on her face as she turns to look at an agitated Demeter. The shot highlights Bombalurina’s concern and attentiveness, following her as she reaches out to her friend.

An Elegant Pair:

Going by screenshots on the WayBack Machine, Demeter and Bombalurina’s page disappeared between March 30th and June 4th, likely in anticipation of the summer trailer. The whole website was redesigned, and its many changes included removing its ‘Meet the Cats’ gallery. Demeter and Bombalurina are the only characters to share a page, besides Mungojerrie and Rumpleteazer, the latter being a set of siblings introduced together in a song. (There’s also a page for “Gus/Growltiger”, but that’s separate, as the same actor plays both characters because the former becomes the latter, reminiscing about a past stage role.) Rooted in the actresses’ nuanced performances and interrelated backstories, the two cat queens are presented as a necessary pair. The ‘Macavity’ duet then binds them in the production and in pop culture.

Going by screenshots on the WayBack Machine, Demeter and Bombalurina’s page disappeared between March 30th and June 4th, likely in anticipation of the summer trailer. The whole website was redesigned, and its many changes included removing its ‘Meet the Cats’ gallery. Demeter and Bombalurina are the only characters to share a page, besides Mungojerrie and Rumpleteazer, the latter being a set of siblings introduced together in a song. (There’s also a page for “Gus/Growltiger”, but that’s separate, as the same actor plays both characters because the former becomes the latter, reminiscing about a past stage role.) Rooted in the actresses’ nuanced performances and interrelated backstories, the two cat queens are presented as a necessary pair. The ‘Macavity’ duet then binds them in the production and in pop culture.

When Demeter and Bombalurina sing ‘Macavity’, outlining his various crimes and misdeeds, they sing a call-and-response in one verse. They list out examples of more normal disturbances, contrasted against the other lyrics about Macavity’s apparent supernatural powers and “depravity”, such as a looted larder and missing milk. They conclude, “Or [when] the greenhouse glass is broken/And the trellis past repair[…]” Bombalurina sings the former line, while Demeter sings the latter; the couplet summarizes Macavity’s destructive nature. The imagery contains elementals associations related to their specific characters.

The cats’ names go deeper into Pagan aesthetic and philosophies. As I mentioned earlier, Bombalurina’s name conjures images of fire. Glass occurs in nature when lightning strikes sand, causing a chemical reaction that produces the fragile, translucent substance. Humans have produced glass for thousands of years through controlling and manipulating fire — the glassmaker’s roaring furnace. When glass is broken, you repair it and/or replace it, moving forward. Greenhouses also function to nurture plants, fitting as Bombalurina protects and cares for Demeter. In regards to the trellis, it represents her role as a nurturer and her damaged self. She can not move past her trauma as easily or as smoothly as Bombalurina can, likely due to their temperaments and differences in severity of abuse, and her emphasis on “past repair” hints at her “tortured soul” as described by her character page. She likely views herself in this way, but she subsumes it in order to be a better member of her tribe.

Tumblr user bethgreenewarriorprincess, a meta writer and Wiccan, once analyzed The Walking Dead in terms of earth astrology. She writes, “Going back to ancient times on a metaphysical level[,] I am reminded of the four sacred directions or the four winds. They also line up with the four elements: Earth, Water Fire and Air.” She frames these directions as an elemental wheel. Earth and fire are necessary opposites: Earth associated with stability, the feminine, and the North; fire with catharsis and change, the masculine, and the South. When I consider Demeter and Bombalurina, they fit relatively speaking into these associations.

For example, Demeter is the more feminine of the two, in my opinion, reinforced by the various character descriptions that reference her “ladylike” nature. Bombalurina has an aggressive edge, such as her dedication to flirting and chasing tomcats. And though ambition isn’t strictly masculine, our culture associates the trait with men because of its relation to aggression and dominance. Bombalurina also has the clearest character arc between the two, growing to accept Grizabella once she acknowledges the old cat’s pain and sees Old Deuteronomy’s acceptance. On the flip side of these associations, Bombalurina provides the support, her being the more emotionally stable of the two. From an elemental perspective, Bombalurina’s fire (related to her disposition) makes it easier for her to purify herself, burning away the past for her health. Demeter’s interpersonal trauma, on the other hand, infects her like pollution, a toxin she manages every day with grace. (Wouldn’t that be an interesting interpretation and/or adaptation of the Macavity-Demeter relationship — an ecofeminist allegory that addressed the intersections of gender violence and environmental toxins?)

In one of her concluding thoughts, bethgreenewarriorprincess notes, “[T]he Earth [is] the foundation for all the other elements.” The earth in its essentialness recalls Xclaim!’s audition list that describes Demeter as “in the middle of all the action.” A genuine Cats adaptation, in order to honor and enrich the material as realized by Andrew Lloyd Webber and his original collaborators, like Gillian Lynne, should honor these two characters’ friendship and recognize Demeter as a worthwhile figure in the story.

Our Cats at the Cinema:

News of this film adaptation date back to February 2016 when The Sun first reported rumors of an adaptation with director Tom Hooper in the works. Variety then confirmed everything that May. Hooper, known for his Oscar-primed epics like Les Mis and The King’s Speech, Hooper adapted the screenplay with co-writer Lee Hall. The latter has writing credits on films like War Horse and Rocketman; he also made uncredited revisions to the 2005 Pride and Prejudice film. Hooper first conceived of the adaptation back in 2012 as he was finishing up Les Mis, and seven years later, it has come to fruition.

When it comes to shifting mediums, the storyline has to be restructured — in this case, from theatre to film. In Lindsay Ellis’s video essay on the 2004 film adaptation of The Phantom of the Opera, one of her concluding thoughts focused on the tension between honoring the source material and acknowledging the medium of film:

This movie needed to be ripped violently out of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s hand and shoved to a studio with a big budget who would actually change some stuff and make the awards-baity movie that they wanted instead of a no-man’s land of a movie that they got.” (t. 40:20-40:35)

It appears that Lloyd Webber learned from his mistakes as he has allowed for the studio to make significant changes. For example, Cats now has a clear protagonist in the white kitten Victoria; Webber went so far as to compose new music for her, which Swift later wrote the lyrics for. It’s now the song ‘Beautiful Ghosts’. Some of these changes, however, deviate too far from the source material, going for a more traditional route in depicting women.

I had my misgivings about film!Demeter early on, as well as about film!Bombalurina. With Demeter, my concerns surfaced after initial cast announcements came out, as Demeter was never mentioned. It appeared that she wouldn’t be played by a Hollywood megastar — and while that isn’t a bad thing or necessarily indicative of a reduced role — it still worried me. A few weeks ago, the film’s Wikipedia page updated and credited Daniela Norman, an up-and-coming British actress and dancer, for the role. Her social media was relatively silent about this role, the movie press focused on the big names and newcomer Frankie Haywood, who plays Victoria.

When a behind-the-scenes (BTS) video dropped, Norman appeared in only one clip, as part of an entourage led by Swift (t. 00:10). It was clear that Hooper and Hall had changed the character dynamic: Demeter no longer stood beside her best friend. She followed. In the second official trailer, fans pointed Norman out as the gray cat who taunts Victoria, Norman’s character asking, “Cat got your tongue?” (t. 00:55). Her first appearance already signals a radical departure from a characterization that spans decades. Hints of her devolved friendship with Bombalurina also had early warning signs. Swift has never mentioned Norman in an interview. Marketing around her has connected Swift to Idris Elba, who plays Macavity. Earlier this year, they presented an award together at the Golden Globes, and in the BTS video, they are seen practicing a dance together (t. 1:41). The final nail in the coffin for the characters’ friendship, in my opinion, hit when verified-Twitter announced the soundtrack. Swift has main singing credit on ‘Macavity’, with Elba listed as a feature. In a recent interview, Hooper implicitly confirmed this too, mentioning, “a number for Taylor and Idris,” (t. 25:27).

Swift’s involvement in the marketing also hinted at a role more prominent than Norman’s. Swift appeared heavily throughout the BTS video, and she was one of the first people to announce something about the trailer, posting a tease to her Tumblr. Unlike Norman, her name appears on the main cast list, per the film’s website. Since this spring, I suspected that Macavity and Bombalurina would be written as an evil duo of some sort, possibly romantic. In May, Swift appeared on The Graham Norton Show and said, “[Bombalurina is] like a manipulative sociopath cat,” (t. 8:58). Then, as I was writing this article, last week Mulderville released an interview with Swift. She explained her character:

Then you have the bad cats which is Macavity and Griddlebone, Rumpelteazer, Mungojerrie, and Bombalurina. Macavity is the baddest bad cat. We kind of are mobsters in this world, where we sort of… we’ll take what we want. We’re not abiding by any cat laws. And just sort of lying, stealing, cheating our way through life. And Bombalurina is sort of this right-hand man for Macavity. (t. 00:44-1:21)

And so, she confirmed months of personal speculation. The film people reworked Bombalurina from her core. They began with little known backstory, and followed a different course, exploring the character that Bombularina could have become if that “rough and hard life” had gotten to her.

Besides its New York premiere earlier this week, the movie hasn’t been released and thus I can’t fully judge it and its characterizations. That being said, official statements and marketing point in a clear direction. Diminishing Demeter’s role troubles me because of all the characters, Hooper and Hall chose to downgrade the feminine women who quietly suffers and quietly endures. It also troubles me that between the two characters, they choose to make the more sexual and sexualized one a villain. It reinforces the message that a sexually liberalized woman threatens the world around her. In addition, the film people then altered a song about women processing abuse from their mutual ex-partner, and instead, they have likely made it into a song where the man is praised by one of these women. Yes, Bombalurina is in a place of power as his right-hand man, but how often have we seen the dastardly villain with the sexy woman as his second-in-command? Even if the relationship was portrayed as toxic, media history shows that too easily general audiences can romanticize such pairings, like the Joker and Harley Quinn.

Making Bombalurina into an antagonist is the easy way out of a story that could have been further developed to better resonate in a post-#MeToo world. Especially since Elba is significantly older than Swift. If the film kept the play’s characterizations and some of the backstories, Bombalurina and Demeter could have discussed being taken advantage of by an older man. Macavity could have been their old boss too if they were once part of his gang.

Overall, when considering sociopolitical factors and implications, abuse is best understood outside the self.

Abuse & Society:

When a person begins to realize that they’re in an abusive relationship, don’t be surprised if they dive into the trenches of the Internet, searching for answers. I know that’s how processing my family’s abuse really kicked off. I waded into Tumblr posts, YouTube videos, scholarly books, and professional articles, desperate for answers and spiraling from the eerie similarities that I would read. This online sub-community is dominated by the most common, interrelated targets of narcissistic abuse — survivors of domestic violence and ACoN’s (adult children of narcissists). One piece of jargon that I always liked was the term “flying monkey”. Inspired by the Wicked Witch’s minions who wreaked havoc for Dorothy, flying monkeys are the perpetrator’s enablers. They’re often narcissistic and predatory themselves, though more covertly, and are sometimes victimized by the perpetrator too. They do the perpetrator’s bidding such as spying on the target and trying to convince them to come back.

When a person leaves an abusive relationship and opens up about it, they will not only lose their loved one. They will likely lose friends, sometimes family, scorch their reputation, and maybe even have to disappear in the middle of the night. It’s a series of tidal waves that no Psychology Today article can prepare you for.

Abusers run their smear campaigns, usually starting before the target has even left, to gain sympathy and to socially gaslight and isolate the target. Flying monkeys, of course, join in, feasting on the drama or squelching any conflict, not wanting to disrupt the group. Lilly Hope Lucario, a writer and blogger on complex post-traumatic stress order (C-PTSD), cites four elements rooted in this gaslighting and abandonment. She organizes it as a series of repeated traumatization.

In addition, Lundy Bancroft is an abuser-rehabilitation specialist with over twenty years of experience. Though he primarily treats men charged with domestic violence, Bancroft sees the abused women and their children as his true clients, as he hopes that by working with perpetrators and by communicating with the targets, he can help the latter lead better lives. In his 2002 book, Why Does He Do That?: Inside the Minds of Angry and Controlling Men, Bancroft discusses the social traumas caused by the perpetrator’s allies. One particularly powerful and vindictive ally can be the perpetrator’s new partner, a woman manipulated and love-bombed herself (p. 282-284). He writes, “[The abuser] maneuvers the woman into hating his ex-partner and may succeed in enlisting her in a campaign of harassment, rumor spreading, or battling for custody,” (p. 96). In some ways, the harassment from the new partner hurts more than the familiar abuse from the perpetrator, an unforeseen betrayal of sisterhood.

Besides the perpetrator’s charms and manipulations, the just world fallacy helps to explain why so many people disavow the target and join in on the shaming. Melissa V. Harris-Perry, whose career spans many areas of politics from academia to editor-at-large for Elle.com, examines this fallacy. In her 2011 book, Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, Harris-Perry discusses the strong black woman archetype and connects it to the stubborn just-worlders, writing:

Psychologists have found that people’s belief in a just world helps explain how they react to innocent victims of negative life circumstances. People become cognitively frustrated when presented with stories of victims who suffer through little fault of their own. They can deal with this frustration in two ways: they can conclude that the world is an unjust place, or they can decide that the victim is somehow to blame. Most people reconcile their psychological distress by blaming the victim. Even when we know that suffering is undeserved, it is psychologically easier to blame the victim rather than give up the idea that the world is basically fair. In some studies, respondents were given a way to compensate the victim, in which case they were happy to make the world seem fair again through their actions. But when they had no chance to make things right and were faced with the knowledge that the innocent victim would continue to suffer, many people tried to find a way to understand this suffering by denigrating the victim. (p. 188)

This is the externalized, social version of targets blaming themselves. So often targets wrack their brains, trying to find a reason to justify the perpetrator’s abuse. It’s about wanting to maintain a sense of control, because if the target caused the abuse, then, in theory, they can stop it from happening again.

For women in relationships with men, there is also the expectation that she handle, if not all, then the bulk of the emotional labor, functioning as a second mother and free therapist. If caring for her partner is her social role and he abuses her, then she must have failed in some capacity, having not rehabilitated him enough. Outsiders will cling to their non-survivor privilege and to social and gender myths, because to face the truth means they must confront an indifferent universe and the fact that it could have been them. A wrathful, moralistic god is easier to swallow than empty winds of chance, after all.

Last year, Katie Presley reviewed Kesha’s song “Praying” for NPR’s ‘The 200 Greatest Songs By 21st Century Women+”, ranking it at twenty-seven. “Praying” was the lead single of Kesha’s first album since her legal struggles began, as she tried to explicate herself from her abusive producer. Presley writes,

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk changed neurophysiology when he argued that “the body keeps the score” — that is, it remembers traumas the mind buries. Kesha changed pop music when she proved it. […] That high note seems summoned by the struggle, possible only because of what her body now knows. In just under four minutes: both wound and recovery.

Her comments get at the primal, visceral power that music holds, how it reaffirms the natural connection between mind and body that becomes disrupted by societal forces. Music allows humanity to feel with its entire being. Her reference to van der Kolk’s work, contextualizing it in relation to music’s cathartic abilities, applies to Demeter and Bombalurina’s ‘Macavity’ performance. By introducing the villain, they control the narrative of what happened to them and who was responsible, as they get to frame him as how they saw him. They draw on dancing and singing to express the interpersonal trauma and the complicated memories that linger beneath the skin.

In the Omnibus ‘Macavity’ rehearsals, Gillian Lynne shows Gardner and Lee-Hill a particular dance move that she wants them to do (t. 14:50-15:18). She sings ‘Macavity’ and as she twirls, she explains, “There’s no one like a stomach ache,” leaning forward, her arms curved as if she were clutching her abdomen. “There’s no one like Macavity” is a central line in the song, so she is equating Macavity to the stomach ache. As I mentioned in my Captain Marvel article, professional research and anecdotal evidence have shown that the gut mirrors our emotional states. Counselor Kris Godinez has likened it to a second brain. Gastrointestinal distress and abdominal pain are common for targets of abuse as their bodies struggle with internalized stress. The motion also reflects Lynne’s earlier comment to Lee-Hill about her character’s relationship with Macavity: “She’s [Demeter] saying, “The man was wonderful when he made love to me, but I hated him!” […] I’d actually like your hands [as Demeter] to feel your own body, as he once did,” (t. 11:36). In that rehearsal, Lynne had ran her hands over her stomach and torso, the abdomen the resting place for a love that soured into hate.

The song-and-dance structure of musicals provides an ideal vehicle to express this interconnection between the emotionality and physicality of trauma. Musicals are theatrical, the numbers hyperbolic expressions of the character’s inner desires, fears, and general worldview; that melodrama is cathartic. Notably, Demeter and Bombalurina still deal with the rippling effects of Macavity’s toxicity, but they commiserate together. Solidarity between women, forged from mutual abuse and kinship, rarely appears in media. Targets often appear as lone survivors in an emotional wasteland, and if they encounter another person victimized by the perpetrator, the person only provides exposition or has villainous intentions. We don’t see a connection develop and stay intact by the story’s conclusion. The movie adaptation will continue the perpetuation of this narrative absence, removing the catharsis of the ‘Macavity’ song in exchange for a sexy villain number.

And in Omnibus, we can see the implication that Lynne intended, to a degree, for their friendship to work as a feminist camaraderie in the face of domestic violence. She discusses the performance with Gardner and Lee-Hill, highlighting the chemistry and nuance that develops due to the many shows that the actresses had performed together:

One of the things that has gone [on] a little bit […] is that moment between these two women who have known intimately the same dangerous man. But I want those moments where you just exchange looks, which is a moment of collusion between you not to go[.] […] Just by a turn of the head. (t. 12:44-13:23).

Audience members see this collusive tilt of the head when Demeter sings, “He’s outwardly respectable.” Bombalurina sashays by, replying, “I know, he cheats at cards,” and Demeter glances up at her. Lynne’s word choice — “collusion” — stands out within the context of the ‘Macavity’ song. The word has connotations of criminal activity, relating to Macavity’s title as the “Napoleon of Crime”. Targets become survivors because they learn to manipulate the game and pick up some of the perpetrator’s tricks. It’s a situation of spiritual life and death. It’s survival, but instead of spears, it’s lies turned back around, secret phone calls with a best friend, and the packed bags hidden away.

The detail at card-cheating and subsequent moment between them is also so relatable and common for targets and survivors. It’s cathartic when a person can vent to someone who experienced the same infuriating quirks and suffocating tactics. These conversations reduce feelings of isolation and recenter the problem, making it clear that the perpetrator, the source of connection, is the actual problem.

Later, the documentary cuts to a conversation between all three women (t. 13:55-14:30). Lee-Hill and Lynne zero in on the significance of two women singing together:

Sharon Lee-Hill: “We had a bit of trouble at the beginning trying to find that rapport, ‘cause when you got two strong ladies together doing a duet… It was quite a long time, wasn’t it? Getting that rapport? We’ve got it together now. And it feels really good.” […]

Gillian Lynne: “At the same time, two women singing together, when you get it right, I think is terribly exciting.”

And it was exciting to watch, for me at least. Though we never see Demeter or Bombalurina come forward about their abuse, everything relegated to backstory, we can assume that they were believed by the tribe. That they believed one another. Rather than be manipulated somehow by Macavity into turning against the world and against their fellow women, they took his darkness that burned hate into their hearts and as their character page stated, “create[d] an even stronger bond between them.” When it comes to Demeter and Bombalurina, their friendship and their shared story offer an alternative look at recovery from abuse. And it’s been that way for almost forty years. The significance of their friendship grows when considering the social ramifications of leaving and outing an abuser. The Jellicle tribe rejected Grizabella for her perceived impurity, her contamination, yet nothing in Demeter’s backstory indicates that she experienced rejection. Her loved one supports her fully when it comes to freeing herself from Macavity.

The Cats film adaptation could have done so much more to develop Lynne, Gardner, and Lee-Hill’s feminist elements, as plot and dialogue could be filtered through a film’s three-act structure and need for exposition. These adaptational changes become more frustrating since Hooper already seeded a connection between women related to trauma: Grizabella and Victoria. The film centers Victoria as the protagonist, the point of view character for the audience, and she stands in contrast to Grizabella. In this retelling, The Hollywood Reporter writes, “The demure Victoria, who makes an entrance at the movie’s beginning as an abandoned kitten carelessly tossed from a car, is as much of an outsider as Grizabella and as eager for an invite to the exclusive Jellicle Ball.”

The song ‘Beautiful Ghosts’ reflects Victoria’s trauma-rooted anxiety and trust issues. She sings about the fear that she will never have good memories to lean on in her old age, as Grizabella does. That the trauma she experienced as a young person will be what defines her life. In terms of trauma disorders, this symptom is known as a ‘sense of foreshortened future’, which is essentially a disruption of how a person perceives time. It’s the belief and experience that one’s life has spiritually ended, that no meaningful events like professional success, marriage, or even a normal lifespan are possible. In a review of ‘Beautiful Ghosts’, Aja Romano pointed out that Victoria went from a silent character “creepily portrayed mainly through her dawning sexual awakening,” to a young woman with a voice, her coming-of-age greater than her body. If Hooper adapted Demeter and Bombalurina faithfully, using the medium of film to delve into their backstories, their friendship could work alongside Grizabella and Victoria’s connection as a possible foil, Demeter a nurturing presence for Victoria and proof of life beyond abuse and abandonment.

Conclusion:

In 2000, one writer summarized the play’s mark on culture: “[M]ore than a financial juggernaut, “Cats”’ fundamentally reshaped the Broadway landscape by ushering in the era of the megamusicals: big, flashy spectacles that required little theatrical sophistication or knowledge of the English language to appreciate.” Cats taps into the emotionality rooted in rich aesthetics, condensed through the universal language of desire and fear, and as a concept is whimsical and weird, two things that our corporate-funded culture sorely needs. We cannot say at the moment if the movie will speak that same primordial language with its marriage of visuals and music, though the retooling of Victoria is promising. Still, my mind keeps wandering back to Demeter and Bombalurina and the lost potential. In a 2012 personal essay on grief and supportive women, Emily Rapp Black wrote, “[F]riendships between women are often the deepest and most profound love stories.” The poignancy of her statement sharpens with a bittersweetness when abuse filters through a friendship, the righteous indignation and feral protectiveness burning between two women. The shared humor from the f*ucked-up absurdity of the whole thing.

Last year, animation student Ilyssa Levy (as ilymation) went viral after she posted the first video in a series about her experience with interpersonal trauma. In two videos, she details how she met and later left her abusive ex-boyfriend, an older man who she met online when she was just thirteen. The third video series plays out as a documentary, following her as she flies along the California coast to meet a woman that he had stalked. Levy had known about the woman beforehand, as her ex had presented the woman as this terrible person who broke his heart. Years later, they laugh over this man’s pathetic quirks; they validate one another’s surreal experience with humanity’s capacity for evil.

The experience though is also a trip for Levy, an opportunity that has her eating crêpes for the first time. Proof that life goes on after trauma, that people will accept and love you. And that they will love you, not regardless of your past, but because of it. So maybe the contradictions that run throughout Cats, that run throughout Demeter and Bombalurina, also represent that the characters survived their backstories. That we all can survive our messy selves, whatever that mess might be, and that we don’t have to survive alone. Because survival is loneliness, it’s a moment. Thriving is looking to the future with someone by our side.