Spoilers for the entire run of Death Note in manga and anime, the Netflix live-action adaptation and the first two movies in the Japanese series of live-action adaptations.

Content warning for discussions of racism, ableism, death, murder and suicide as depicted in the various media.

Netflix’s controversial adaptation of Death Note was released on August 25th to generally mediocre reviews and a solid 40% on Rotten Tomatoes. This latest installment in a string of questionable western adaptations of acclaimed Japanese anime has something that Ghost In The Shell and Dragonball Evolution didn’t: a pre-existing, critically acclaimed Japanese live-action adaptation to stand up to. Nippon TV’s first Death Note movie was released in 2006 to very positive fan and critical reception and spawned a whole franchise of live-action movies and TV shows that are still being produced. With improvements in filmmaking technology over the past eleven years and with Netflix providing far fewer creative restrictions than Nippon TV, Netflix’s adaptation had plenty of opportunity to improve on the work of its predecessor and…did not.

Why did Nippon TV’s adaptation of Death Note hold up so well while Netflix’s work is struggling? The transplanted setting has definitely drawn a great deal of criticism, but the two adaptations also approach the work as a whole in very different ways. Changing aspects of a work when adapting it into another medium is not inherently wrong. However, those changes must always serve a purpose.

To that end, I want to look at both movies by comparing them in several crucial areas over three articles: character and action, story and themes, script and imagery. The adaptors’ choices in each of these areas—and which area the adaptors have prioritized in terms of fidelity—are key to understanding which (if either) adaptation was more effective and why.

To avoid confusion, the original manga and the extremely faithful anime will be referred to as Death Note; the Netflix adaptation will be referred to as Death Netflix; Nippon TV’s adaptations will be referred to as Death Nippon; and the titular piece of murder stationary itself will be referred to as the Notebook. While Nippon TV has produced multiple movies and TV shows, in the interests of fairness, only the first Death Nippon movie will be explored for the purposes of this article.

Characters

Death Netflix

Likely as a result of its short runtime, a relatively brief 100 minutes, this adaptation has an extremely minimal cast. The story was reduced to only six significant on-screen characters: Light Turner (the Americanized version of Light Yagami), his father James Turner (counterpart to Soichiro Yagami), Mia Sutton (loose counterpart to Misa Amane), L, Watari, and Ryuk. Of the early cast in the manga, Light’s sister is nonexistent and his mother was killed offscreen, something that becomes a plot point. There’s no Rem because there’s only one Notebook, and there is no counterpart to Naomi Misora or the entire Kira Task Force. As a result, Light’s father has nobody to work with to catch Kira except for L and Watari.

Light’s mother and sister are actually very significant omissions. Light’s affection for his sister Sayu was, early on, one of his most sympathetic traits. His slide from wanting to make the world better for people like her, to being afraid that he might have to kill her, to coldly calculating when to kill her for Kira’s benefit, is an effective marker of his slide down the slippery slope. That said, the addition of a Sarah Turner to Death Netflix might have been useless, as Light doesn’t go down a slippery slope at all. In fact, there’s very little shift in his moral stance from the beginning to almost the end of the movie, and a lot of that is to do with his mother’s death.

Mrs. Turner died by being run down by a criminal, though whether by accident or on purpose is unclear. Nevertheless, both Light and his father are tortured by the fact that the man walks free of any punishment through implicitly illegal connections. This recontextualizes Light’s entire approach to the Notebook.

It’s a very long time in Death Note before Light Yagami kills anybody who isn’t a criminal or a law enforcement official trying to capture him, but Light Turner’s first two kills are both extremely personal. Rather than testing the Notebook on a random thug in the street, he tests it on a bully was a victim of. Before starting to mass-murder criminals, he kills the man who killed his mother. Moreover, Light Turner only commits one murder in the entire movie without prompting, and that’s when he kills his mother’s murderer. Every other killing is prompted by either Ryuk or Mia.

This change of motives helps to explain why Light Turner does not go through Light Yagami’s moral decline. Changing the world isn’t his initial plan for the Notebook, it’s something he goes for (with some pushing from Mia) after achieving personal revenge. Because changing the world isn’t his idea, he’s never committed to it the way Light Yagami was. Light Yagami decides that he is a good guy and therefore whatever he does is good; Light Turner wants to be a good guy and, later in the movie, expresses a fear of becoming a bad guy by killing police officers and FBI agents. This is a completely different evolution from Light Yagami, who continually shifted his definition of “bad guy” to justify his own actions.

Light Turner, in another contrast to Light Yagami, is not portrayed as a genius. A part of this is due to the setting; the average American high school does not track and rank students’ academic success the way that Japanese high schools do, and reaching university in America is far less dependent on exam scores. But rather than figure out what would be the American equivalent to Light Yagami’s status as a brilliant student, something that makes him an ideal example of a teenager in his society with an array of options in terms of his future, Death Netflix went in the opposite direction. They made Light Turner a loner outcast.

He has less in common with a paragon of society and more with the kind of kid a lot of people, in America, would half-expect to turn up to school with an automatic rifle someday. He’s a sullen loner who wears a lot of dark clothes, has ugly frosted tips, comes from a broken home, and has major issues with authority.

The writers chose to sell that stereotype—a very unpleasant one at that, to suggest that ’emo kids’ are more likely to be dangerous murderers—instead of exploring the uncomfortable truth that the mass-murderer in the class is just as likely to be the friendly, smart, attractive boy from a good home two desks over. All of this seems designed to make his transformation into a mass-murderer simpler to follow, but it also makes him less compelling and interesting as a character. Light Turner has none of Light Yagami’s charisma and displays nothing resembling his manipulative genius until the very end of the movie. Instead, he spends a good deal of the movie being jerked around by L, Ryuk, and Mia.

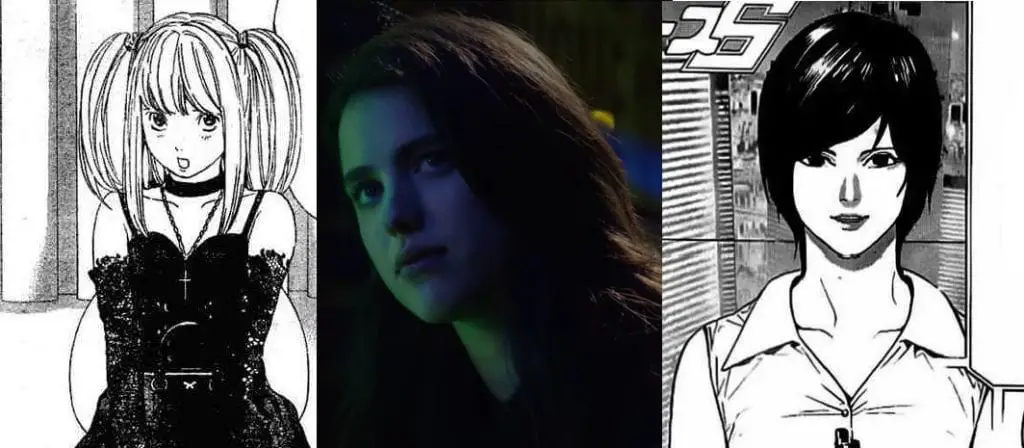

While Misa Amane’s love for Light Yagami was the reason she started to commit murder, Mia Sutton’s ladyboner for murder is the reason she gets involved with Light Turner. The reversal is so complete that really, vaguely similar first names and position as Light’s love interest aside, there’s nothing to connect her to Misa. In fact, Mia has a lot more in common with Kiyomi Takada, a character who appears in the second half of Death Note. Kiyomi is a dark-haired woman whose admiration for the murders that Kira commits leads to her having a relationship with Light. She takes part in several of his gambits to hide his identity from the police and, ultimately, dies when Light writes her name in his Notebook as part of an extremely complicated plan to save himself.

Mia, however lacks the development of Misa or Kiyomi. Death Netflix attempts to give her an arc wherein she’s so consumed by her lust for power that she’s willing to betray Light for the Notebook, but her betrayal feels hollow when there was nothing between then from the beginning but the Notebook. They’d never even spoken before Mia approaches Light about witnessing the bully’s death. This makes it all the more jarring that Light’s idea of flirting is to show off his ability to murder at will with the Death Note. And that Mia’s response to this isn’t to immediately run, but to jump his bones.

Her true interest being the Notebook is obvious from the start, so there’s no emotional investment in them trying to kill each other. Her telling Light that she loves him after they fell out because she tried to murder his father comes off less like a genuine confession and more like an act of manipulation that she knew would work on a guy who was so affection-starved that he told her his deepest, most dangerous secret just for starting a conversation with him.

In this, Mia is far more like Light Yagami, who used Misa Amane and Kiyomi Takada in this exact way, than Light Turner is. In fact, Mia has far more in common with Light Yagami than Light Turner does overall. She pushes him into committing the mass murder of criminals, and is the one who wants to take the step to killing police officers hunting Kira. She’s even willing to murder Light’s father when he challenges Kira to kill him on live TV. But the way the movie frames their relationship seems to jerk back and forth at random between Mia as a manipulative psychopath and their relationship as a fun case of Mad Love that’s ruined by the Notebook’s power.

Like Light and Mia, Ryuk has also undergone a motive flip for Death Netflix. He isn’t curious about what Light will do with the Notebook because he’s bored. He is actually shown to be involved in the murders directed by the Notebook and seems to find them great fun to carry out. Unlike Ryuk’s pointedly neutral stance in Death Note, the Ryuk of Death Netflix seems very invested in Kira killing as many people as possible.

This change is likely a result of the cultural shift. The Ryuk of Death Netflix is not really a Shinigami, who only kill humans to steal their un-lived years for themselves; he’s more like a western idea of a demon trying to lead a person to sin. In fact the Netflix description of the film directly refers to him as a demon. He constantly tempts Light and Mia into committing evil for no apparent reason other than that he is evil and delights in suffering and corruption. This shift also serves to make him much more villainous than he originally was and Light Turner, the guy who kills over 400 people in the course of the movie, more sympathetic.

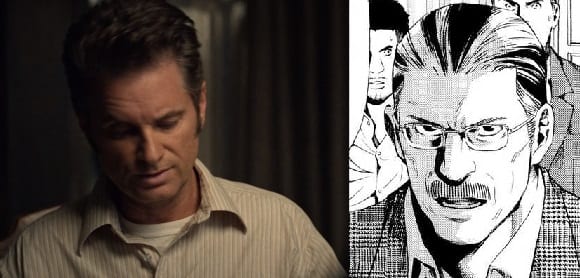

Probably the most faithfully adapted character is Light’s father, James Turner. Like Soichiro Yagami of Death Note, he has strong moral convictions, enough to hunt Kira alone if he has to. The most notable difference is that, unlike Soichiro, James is a widower. Yet despite the personal stakes in what Kira does and the relief that his wife’s killer is dead, James still believes that Kira’s killings are wrong and deserving of punishment. This steadfast morality was a key aspect of Light’s father in the manga, who was positioned as the top of the moral scale his son fell to the bottom of.

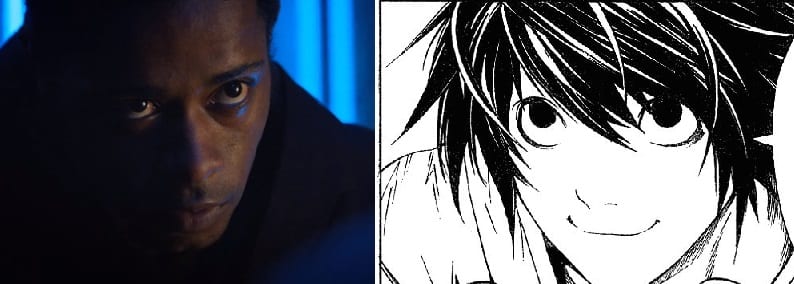

L is another character who, for the first half of the film at least, is adapted quite faithfully. Lakeith Stanfield puts on an excellent performance as the eccentric detective. The odd way that he moves and holds himself, along with the rapid yet precise way that he talks, is an effective adaptation of the L of Death Note, though one that seems designed to make him a good deal more jittery than the original.

However, there’s a significant shift around the time that Light, in a move original to Death Netflix, takes control of L’s assistant/handler Watari. L becomes much more aggressive and desperate in response to losing Watari, ultimately chasing after Light with a gun and, in the end, potentially writing Light’s name in the Notebook. The L of Death Note does get upset when faced with Kira killing people and Watari’s death. But in the time between Watari’s death and his own, he regains his composure enough to realize the implications of what just happened before Rem can kill him. He dies content in the knowledge that he was right about Light being Kira.

Death Netflix’s L shows none of his originator’s calm composure under pressure, instead becoming a needy, angry child without Watari. This character shift is entirely in service of a more “action-packed” finale. The L of Death Note does not handle guns and, aside from one brief display of capoeira, never engages in physical combat. His battles with Kira are entirely intellectual and breathtaking in their complexity. But as neither Light Turner nor Mia Sutton are as intelligent as Light Yagami, none of those stunning mental battles are on display. Instead, there is a fairly generic chase scene where L hunts Light down with a gun, before being unceremoniously knocked out before the climax. Ultimately, he seems to be within inches of actually using the Notebook on Light, something that L joked about in Death Note but would never have done.

I feel like this is an important time to mention that, when assessing these characters as adaptations, I am trying to avoid the issue of race, specifically of whitewashing and ‘racebending’. Not that I don’t think that there are serious issues with taking this story out of its cultural context, nor that there are major problems with the lack of Asian-American representation in American media. I am just a white girl who is under-qualified to talk about the problem with race in western cinema, and a great deal has already been written on the subject by better and more informed writers than I.

But I really do feel that there are some exceptionally unpleasant implications to making L much more aggressive when casting him as a black man. And, there are equally unpleasant implications to downplaying his intellect in favor of making him jittery, needy, and socially troubled in ways that are unlike his manga portrayal but very suggestive of mental illness stereotypes. Death Note’s L was assumed by many fans to be somewhere on the autistic spectrum, but his behavior never caused him to lash out or become dangerous to other people the way he does in Death Netflix. This carries its own set of extremely unfortunate implications when combined with our cultural narrative of people with autism and mental illness being inherently dangerous.

As much as I think Lakeith Stanfield gave a great performance with what he was given, what he was given was unpleasant on multiple levels. It’s a more isolated problem than the movie’s whitewashing and the complex issue of racism in the US, but it’s still a problem that sticks out when assessing the way these characters have changed in the journey from source material to Netflix..

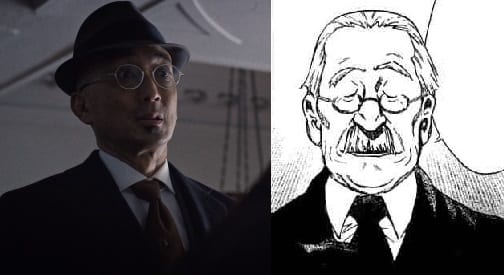

The final character of importance in Death Netflix is Watari, the only character to have been race-shifted in the opposite direction. Death Note’s Watari was an elderly white Englishman. Paul Nakauchi is significantly younger, though he plays the role with the seriousness of an older man. A surprising change is that his name actually is Watari (and only Watari). In Death Note Watari is very obviously a fake name, one that protects him from Kira for half of the manga. That Watari uses his real name and lacks a mask, while L uses both a mask and an alias, is a bizarre oversight given that L figures out very quickly that Kira needs a name and a face to kill, and especially given how important Watari is to L. However, Watari has very little character outside of his place in L’s orbit, serving basically as a servant/handler, and resisting the Notebook’s control enough to delay giving Light L’s name.

All in all, I feel like the only character to have been adapted with respect to their core values is Light’s father. Light, Mia and Ryuk have all received complete reversals in terms of their backgrounds and motivations. Ryuk, at least, is consistently entertaining, but he doesn’t get anywhere near enough screentime to balance out the blandness of the rest of the cast. The lack of any actual relationship with Light makes his apparent betrayals ring just as hollow as Mia’s. L seems to have been scripted with only a superficial understanding of him as a weird genius without examining his underlying commitment to justice, his quite lighthearted sense of humor, or his general fondness for people. He has more in common with the asshole geniuses of western media like Moffat’s Sherlock than he does with Death Note’s L.

The core of the problem is that the writers were unwilling to find an American equivalent to Light: a successful, popular young man with the world at his feet and the capability to do great things in the world. The tragedy of Death Note is that boy, with infinite potential, becoming history’s greatest murderer. Instead, when designing the characters, the creators seem to have looked at the Harajuku Goth aesthetics that made the series so beloved by Hot Topic merch and ran with it. Basing characterization on aesthetics shows a truly fundamental misunderstanding of Death Note, where the very worst people were normal and successful on the surface, while one of the most heroic characters was L, the genuine loner who defied social convention.

Even considering the characters independently of what they’re adaptations of, Light Turner and Mia Sutton are not particularly interesting or compelling people. Angry white kids wanting to kill people is, let’s be honest, neither original nor interesting. The movie does not put in the work to depict them as normal, if troubled, kids who still had the potential to have good lives before the Notebook corrupted them. Instead, it sticks with the lazy, easy story that they were already corrupted, already inherently susceptible to murder because of how edgy and antisocial they are.

In a nutshell, the characters in this adaptation are all looks and very little actual character, which is uninteresting as an independent piece of work and downright tragic as an adaptation of a piece of media with famously compelling characters.

So, how did the Japanese adaptation do it?

Death Nippon

A brief glance at the cast list shows more than twice the number of characters in Death Nippon as there are in Death Note. Light’s whole family is present, including his mother and sister. Several police officers are on the Task Force with Light’s father, as well as Raye Penber (renamed Raye Iwamatsu to make him Japanese instead of American) getting the spotlight among the FBI agents and his fiancee Naomi Misora getting a spotlight role after his death. There are even couple of entirely original characters in Light’s girlfriend Shiori and the massively expanded character of Takuo Shibuimaru. At 125 minutes, it’s a fairly sizable movie with plenty of room for such a large cast, with no notable omissions among the key characters of Death Note’s first arc.

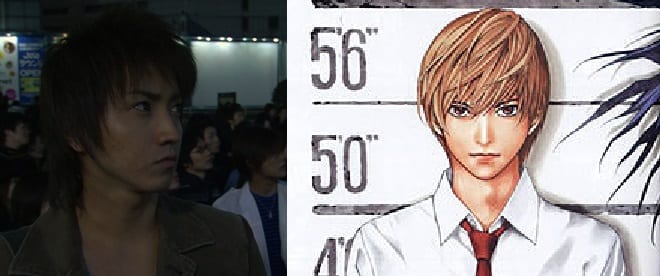

The protagonist, Light Yagami, has been shifted in age slightly, in university rather than in high school. He’s a prodigy, though, excelling at law school, attractive, and athletic; he’s popular with his classmates, has an attentive, loving family, and is in a stable, happy, and undeniably sweet relationship with Shiori. To those unfamiliar with Death Note, it’s a shock to discover that this is the young man responsible for the several ugly, visceral deaths the movie opens with.

He’s actually noticeably less sociopathic than Death Note’s Light Yagami, both in how genuinely tender his relationship with Shiori is and how one of his first murders is personally motivated. As mentioned above, Death Note’s Light doesn’t kill for personal reasons for a long time. Death Nippon shows a number of original scenes of Light taking a personal interest in Shibuimaru’s faked insanity defense, at one point following him to a club and confronting him before breaking down in rage that there’s nothing he can legally do to stop this man from killing again. Light’s hatred of the criminals of the world is much less clinical than Death Note’s Light, and he seems to feel the suffering of the victims of violent crime much more deeply.

This tenderness is far more than Death Note’s Light ever displays, but it also serves to make his full transformation into Kira at the end of the movie that much more chilling. Yet the busjacking sequence still manages to foreshadow this transition. Light brings Shiori into a situation that he’s designed to be dangerous and, though his plan does preclude her getting shot, it terrifies her enough to require a trip to the hospital. Though he still treats her with care throughout this sequence, he shows no regret.

After Naomi kidnaps Shiori, Light’s desperate pleas for Shiori’s life, last kiss with her, and his wailing over her body are all utterly heartbreaking. Until the moment where, alone with Ryuk, Light admits that he orchestrated everything, including coldly calculating how to circumvent the Death Note’s rules to make Naomi kill Shiori and then herself, all to make himself seem more innocent. Light sacrificed Shiori, who believed in him and defended him against Naomi, just to make himself safer. This is unambiguously an act of true evil and ends the film with Light becoming the most iconic version of himself—the remorseless chessmaster Kira, who stands toe-to-toe with L in a war that could shape society’s future. Tatsuya Fujiwara pulls off an impressive performance, heartrending and terrifying in turns.

Shiori, though an original character, is decently developed during the movie outside of her relationship with Light. She’s a law student who expresses strong convictions, speaking passionately against what Kira’s doing because there’s neither due process nor accountability to it. She seems very fond of, and beloved by, Light’s family as well as Light himself, though we don’t see her with any friends or family aside from Light. She’s shy about affection in public places but truly loves Light, even defending him against Naomi’s accusations. Though her actions in the final museum scene are influenced to a certain degree by the Notebook, she seems to get shot while moving to protect Light. Shiori’s innocence and genuine love are such a direct contrast to what Light becomes that she supplants Sayu as Light’s most sympathetic counterpart, one that he willingly chooses to kill off in order to become Kira.

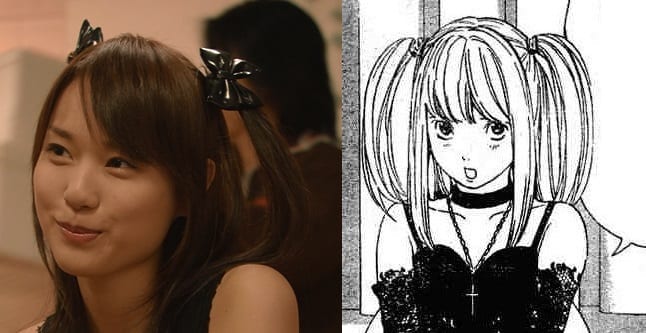

While Shiori is an original love interest , she doesn’t completely replace Misa Amane. Misa’s first appearance is as a poster on the side of the bus that Light arranges to be hijacked, and later we see some of her cooking show, which Ryuk seems particularly interested in. It’s never entirely clear why Ryuk is so amused to see Misa; she doesn’t have a Notebook until the end of the movie, so when Ryuk sees her on television she doesn’t yet have Shinigami Eyes, Rem, or a missing life-number. She’s not cooking with apples or anything else that Ryuk would be interested in, so his entertainment is somewhat inexplicable. It seems to be intended to foreshadow her importance to the second movie, though it potentially undermines, for a viewer unfamiliar with Death Note, the surprise of Misa receiving a second Notebook in the last scene.

Admittedly, Misa doesn’t yet have much of a characterization. She’s an orphan, a Kira worshipper, and an idol with an aesthetic very distinctive to the Japanese idol scene of the early noughties. To Death Note fans, she’s a faithful adaptation with a lot of potential in the second movie, but to movie-only viewers she’s likely a very random (if interesting) little sequel hook.

Of the main Kira trio, Ryuk is definitely the most faithful to the source material. While the CGI has not aged well and the way he moves is downright janky, it’s not utterly unwatchable; Shidou Nakamura’s very entertainingly hammy in how he cackles out Ryuk’s lines. His visual design, lines and behavior are all lifted almost verbatim from the manga. He also persistently refuses to go out of his way to help Light. He is, for the most part, just funny, floating around in the background and being weird with occasional spouts of exposition, which is pretty faithful to the source material. Ryuk was never that deep to begin with; he’s largely popular for his alien morality and values, as well as sheer entertainment value.

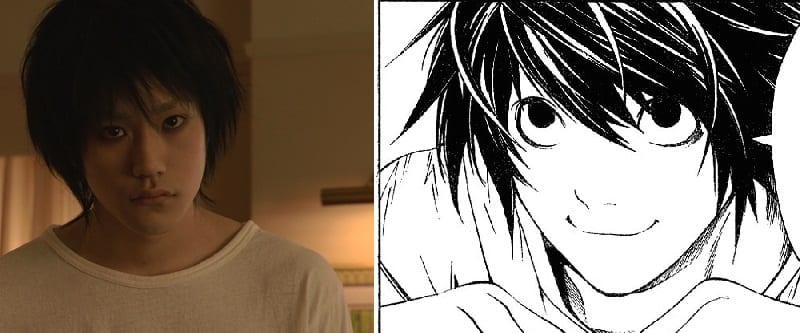

L is another character that seems straight off the manga pages. Kenichi Matsuyama looks like he was grown in a vat for this role. He’s lazy, ponderous, and completely self-assured in his own logic and conclusions. L’s introduction, in each of its stages, is identical to the manga—appearing first as a voice over, then behind a condemned convict pretending to be him in order to trap Kira, and finally revealing himself as an odd but brilliant young man to the police officers willing to risk their lives to stop Kira.

He takes great care at every stage to protect his and Watari’s identities from Kira. He also homes in on Light as his primary suspect extremely rapidly and from there stays very focused on him. Death Nippon establishes him well as Light’s equal and rival before we’ve even seen his face. He’s persistently focused and brilliant, and sometimes seems unfeeling about those who are killed by Kira. But, he’s never condescending towards the police and expresses a genuine belief in justice. His fondness for trolling Light also finds representation and is precisely in keeping with L’s behavior throughout his and Light’s “partnership” in the Kira Task Force in the manga.

As with Death Netflix, Watari is not played by a white Englishman; this time he is portrayed by the stately Shunji Fujimura. He has no role outside of his job as L’s assistant and his true name, like L’s, is kept extremely secret to protect both of them from Kira. There’s really not a lot to say about his presence, honestly, except that as with Death Netflix it’s both accurate and a necessity to keep L a mystery.

Light’s father, Soichiro Yagami, is another well-adapted central character, as is the whole Yagami family. Sayu and Sachiko aren’t really characters so much as set dressing to showcase what a happy, wholesome home Light comes from. Soichiro is interesting in that, as in Death Note, he is first introduced as a senior police officer taking charge of the investigation into Kira. He remains on the Kira Task Force even after discovering that Kira is willing to kill law enforcement officials and dedicates himself full-time to capturing the mass murderer. He refuses to suspect his son, but allows him to be investigated because he believes the investigation will exonerate Light. Takeshi Kaga is very paternal in the role, which is a delight to watch, and Soichiro’s determination to do the right thing and his kind nature make him a very likable character.

A tertiary but extremely popular character who I personally was utterly delighted to see in Death Nippon is Naomi Misora, portrayed stunningly by Asaka Seto. Her short manga appearance was expanded into the driving force of the third act. After her fiancee, Raye Iwamatsu (name changed from Raye Penber, presumably to allow them to cast a Japanese actor instead of an American) is murdered by Kira, she starts her own investigation. She’s a bit of a wildcard in the conflict between Light and L, as it’s some time before either of them have any idea that she’s involved; she’s extremely intelligent and competent, enough to hone in on Light almost as fast as L does. Unlike Death Note, though, where Naomi does not survive her first encounter with Light Yagami, the Naomi of Death Nippon is much more careful.

While her actions throughout the museum sequence cannot necessarily be called her own due to the Notebook’s influence, they are convincingly sold as her own actions until the reveal that Light manipulated the whole setup. Taking Shiori hostage to pressure Light into revealing himself, accidentally hitting Shiori with a warning shot and killing herself out of the horror of having murdered an innocent young woman are all in-character for the grieving but determined woman, as is the fact that she’s careful enough that only a stroke of pure bad luck gets her killed. She’s depicted as having a genius level intellect, which is consistent with her character in the manga. In fact, creator Tsugumi Ohba has explained that while Naomi had been planned to be a long-term enemy of Kira in Death Note, he wound up having to kill her off quickly because she figured out the whole plot much faster than he’d planned.

Also present and named in Death Nippon are FBI agent Raye Iwamatsu, excitable young police officer Matsuda, the more senior and quiet officer Mogi, the suspicious police officer Aizawa, Lind L. Tailor, the death row convict who L uses as a stand-in, and Takuo Shibuimaru, Kira’s first victim. Matsuda, Aizawa and Mogi, however, exist in Death Nippon in a somewhat reduced capacity compared to Death Note.

Takuo Shibuimaru, by contrast, has a greatly expanded role. In Death Note, he’s a random street thug who Light selects as his first victim simply because he and his gang are harassing a woman outside of the convenience store and Takuo’s the only one to state his full name aloud. In Death Nippon, he faked an insanity defense to escape murder charges and then laughed about it with his friends, which is overheard by Light. Light takes up a personal hatred for Shibuimaru and, after testing the Notebook on a random criminal on television and confirming its power, Light deliberately uses the Notebook to murder Shibuimaru.

Overall, the cast and characters are mostly quite close to what they were in Death Note. What changes are present are there to make Light gentler and more sympathetic, which in turn makes his final reveal—that he planned out Shiori’s death—a gut punch, even for those who knew what he would ultimately turn into. Hell, I’ve watched this movie five or six times and I still feel a shiver down my spine when Light looks up from his “crying” to explain what he did to Ryuk.

How do they compare?

As you can probably tell, I’m far more approving of the character changes in Death Nippon than Death Netflix. In Death Nippon, the changes primarily exist to make Light’s transformation into Kira more crushing, and all other character changes bounce off of that. In Death Netflix, every effort seems to have been made to make Light (and Mia) unsympathetic in order to make them closer to the American stereotype of teenage ‘antisocial killers’. Where making Light in Death Nippon more sympathetic has the ripple effect of making the whole cast more likable, making Light in Death Netflix more sympathetic involves making the whole cast unlikeable so that he’s not the lowest of the low.

Death Nippon is also much more faithful to the source material, which is by no means the be-all and end-all of an adaptation’s quality, but is definitely the fast way to the hearts of the built-in viewership of fans of the source material. Indeed, Death Nippon could be accused of pandering to those fans in massively expanding Naomi Misora’s role, but they did so in a way that remained respectful of her intellect and position as one of Light’s most dangerous enemies and one of L’s most trusted allies.

Death Netflix might have been better off as a sort of alternate universe where Ryuk dropped the Notebook in America rather than Japan, exploring the Notebook users as completely different people rather than pretending they have anything to do with the characters of Death Note. Light Turner’s motivations and background are wildly different from both the manga and movie versions of Light Yagami and Mia is basically an original character already.

Yet even as an alternate universe, Death Netflix feeds into stereotypes rather than challenging them. It defangs its own horror by selling the comfortable lie that it’s easy to tell who dangerous people are at a glance rather than the uncomfortable truth that apparently pleasant, smart, charming people can hide unimaginable secrets. It replaces psychological horror with gory headsplosians and Willem Dafoe’s cackling (which is itself somewhat neutered by Nat Wolff’s hilarious screaming).

Death Netflix had a golden opportunity to really delve into the different ways that American and Japanese people regard authority, the police and the justice system, and the very different ways that the justice system works in America and Japan, and it just… didn’t. Light gets some cookie-cutter lines about people in positions of authority not using their power to make things better for others and that’s it. Light Turner says absolutely nothing interesting or original about power or corruption, and his blandness taints the entire movie.

In short, one adaptation took what was frightening about Light Yagami and tried to do that but even more so, while the other decided to throw out everything that was frightening about Light Yagami and do something that is, as far as western media goes, neither original nor particularly effective. If you’re going to make a significant departure from famous and well-loved characters, you’d better have something really good to replace them with, and Death Netflix does not.

Actions

When adapting a story, it’s important to think about the actions that characters take and why. Several key moments were adapted in both Death Netflix and Death Nippon, but both adaptations also added their own, making characters behave in new ways.

The inciting action of the whole story is, of course, Light finding the Notebook, deciding to pick it up and investigating its use. Both adaptations change a good deal about when and where these things happen. In Death Note, Light spots the Notebook on the ground while at high school and reads it on his way home, testing it on a street thug on the way. In Death Netflix, the Notebook again appears to Light at school, but it drops ominously and obviously to the ground during a rainstorm instead of appearing unobtrusively on the ground. Light picks it up, but doesn’t use it until he meets Ryuk. Death Nippon is between the two; Light finds the Notebook in the street, not at high school, as he’s no longer a student. He tests the Notebook when he gets home, but after finding out that its power is for real he does not use it again until he sees a criminal that he has personal hatred for.

Neither adaptations of Light begin committing mass murder until after they’ve met Ryuk, a significant departure from the manga. Death Note’s Light feels guilty about his first murder, but after assuring himself that it was for the greater good, he dives full force into believing that he, as a genius and superior student, has every right to decide who deserves to die. Death Netflix’s Light is never this chilling, and only commits his first murder out of a combination of personal hatred and pressure from Ryuk. Ryuk appears to him less than a day after his first kill and mere hours after he realizes that the Notebook’s power is for real, so there’s really no time for Light to go through the self-reflection and make the decisions that he did in the manga.

Moving up Ryuk’s introduction, in both adaptations, changes Light’s motivations, but in only one adaptation does it also significantly change to Ryuk’s character. In Death Nippon, Ryuk’s explanation of what he is, how the Notebook works, and that there will be no punishment for Light beyond his own pain and fear are all very faithful to the manga. The significant omission is that, because of how early Ryuk meets Light, Light has not yet filled the book with over a hundred names.which in Death Note fascinated Ryuk because he’d never seen a human put the Notebook to such prolific use. In Death Netflix, however, Ryuk plays like a cheap B-movie monster, complete with flickering lights, blowing papers around, and a jumpscare. Ryuk also explains that the Notebook is real before Light investigates it and prompts him to commit his first murder, making Ryuk more actively malevolent and Light less dangerous.

Changing this scene and how Ryuk chooses to present himself to Light changes his entire characterization. I can’t help but feel that Death Netflix, had it been interested in telling a good story in the Death Note universe, might have benefited from making a different Shinigami, one who enjoyed killing. They could even have had the new Shinigami and Ryuk meet because Ryuk wants to watch the show. As it stands, this first scene with Ryuk is a big part of why Death Netflix’s character has nothing in common with Death Note‘s except name and appearance. While he’s independently entertaining enough, it’s not a popular move for fans of the original and it seriously defangs Light as an antagonist.

The third key action to have been adapted by both movies is L’s introduction to the police and the press conference challenge that he issues to Kira. In Death Note, after L introduces himself to the police via a laptop carried by Watari, he challenges Kira. This challenge consists of a man named Lind L. Tailor appearing on television, claiming to be the great detective L and saying that he will catch Kira, who is nothing but a cowardly murderer. This enrages Light enough to kill Tailor, inadvertently giving away his location. L, his face still hidden and his voice altered, challenges Kira to kill him again, and Light can’t. It’s the beginning of L and Light’s rivalry, and it’s the moment that Light crosses the line from only killing criminals to killing anybody who opposes him. This was adapted almost exactly in Death Nippon. In Death Netflix, however, things are very different.

L appears to the police in person from the beginning, rather than anything about his identity being kept secret. He’s wearing a mask, but it’s still sloppier than L’s ever been about his identity in any other adaptation. Lind L. Tailor is also entirely absent; L makes his challenge personally, although masked and with his name hidden. It’s then followed by a similar conference from Light’s father, where he likewise issues a challenge to Kira to kill him.

More than anything, it’s the timing of these actions that change their place in the story; L doesn’t use the press conference to find Kira’s location, he already knows it and uses the press conference to…let Kira know he’s out there and piss him off? Letting Mr. Turner hold his own conference is just confirmation for the fact that he already knows that Light is Kira. Changing how and when L uses the press conference, though, changes the impact of his very first clash with Kira. This L is not a genius rival on even footing with a young man who thinks of himself as a god; he’s an impertinent annoyance for the “hero” of the piece whose deductions are rarely explained.

For a movie that seemed to be focused on having as much flash as possible, reducing the impact of L outwitting Light for the first time seems counterproductive. But perhaps that’s the point, L does not outwit Kira. He never does. A battle of wits, no matter how shocking, is not what this adaptation is here to show. Too much thinking, not enough running around with guns, I guess.

The final action to be adapted by both versions is the murder of the FBI agents. The whole undertaking is Light’s first complex gambit, one that shows a breathtaking level of planning and manipulation. At the same time, it shows how self-sabotaging Light’s hubris is; he played the innocent so effectively that Raye, the agent assigned to tail him, was about to mark him down as meriting no further investigation, but, killing the agents confirms to L that Kira is among the people being investigated. Aside from Naomi being present when Raye dies and Shiori being on the bus with Light, Death Nippon’s portrayal of the busjacking and Raye’s death are as close to identical to the manga as possible.

There’s no show of Light’s intelligence or hubris in Death Netflix because he has neither. He isn’t even the one who kills the FBI agents; for a while, it looks like Ryuk did, but ultimately it’s revealed to be Mia. The change affects how we view both Light and Mia. Murdering twelve FBI agents is unambiguously evil, but so is “executing” over 400 people with no due process. Yet Death Netflix frames only one of these actions (Mia’s) as a truly heinous crime that’s crossing a moral line. Death Netflix does not seem interested in making us feel conflicted about the Light. Rather than being impressed and horrified by Light’s actions at the same time, it pushes us to root for Light over Mia by giving her his very worst actions. That it’s pushing for us to root for Light at all, though, seems to indicate a fundamental misunderstanding of just how evil murdering over 400 people is (others have made a similar mistake recently).

While Death Netflix goes off on its own very quickly, an original action that I think merits examination is Light controlling Watari to find out L’s name. He writes Watari’s name and the instructions to become obsessed with finding out L’s real name and to report his findings to Light’s mobile number. He intends to burn the page with Watari’s name on it in order to stop Watari from dying, using a Notebook rule original to Death Netflix, but Mia steals the page, causing Watari to die immediately before revealing L’s name.

Jeezy peeps. Where do I start? First, on what basis do they expect anybody to believe that “Watari” is Watari’s real name? Even setting aside that he’s being played by a Japanese-descent actor in order to make it more plausible, that’s still not how Japanese names work. Did they really put no effort into investigating that?

And with the lengths that L goes to to protect his own name and face, why would Watari be subject to none of the same precautions? Moreover, Light decides from the beginning that he isn’t going to kill Watari because Watari isn’t a criminal, but he speaks to Watari without disguising his voice on his personal phone. He gave L’s closest assistant his actual, real phone number. A number attached to a phone that will show up with either him or his father as the account holder. The only reason this isn’t the most ridiculously inept thing that Light does is because he already showed off his ability to murder with magic to a girl he just met because he got the bizarre idea that this would get him laid and it mysteriously worked. This is not a battle of stunning intellects, this is a pair of completely inept little boys snarling at each other and tripping over their own feet.

The second original action in Death Netflix is Light’s murder of Mia. It’s significant in that it finally shows some actual planning and manipulation and in that it contrasts with Light’s murder of Shiori in Death Nippon. When Light Turner finds out that Mia has written his name in the Notebook and will burn his page if he hands it over to her as the new Keeper, Light comes up with a plan astonishingly quickly. He writes elaborate instructions for Mia’s death that lead to his page being burned, and controls two sex offenders to have himself and the Notebook rescued from the river and spirited away, with criminals continuing to die while he himself is in a coma.

Light’s motivations throughout this sequence are somewhat murky. He expresses pain when explaining how he killed Mia to his father and screams in anguish when Mia takes the Notebook from him, which setting her own death in motion. But he wrote her taking the Notebook from him in her death instructions. So, it’s unclear if defying the instructions could have saved her life, or if Light just didn’t fully understand how the Notebook worked and really thought she would live if she didn’t take the it. Or, maybe he was lying and only pretending that things were spiraling out of his control? I can’t figure it out. The musical choices really don’t help. Are we supposed to perceive them as truly in love, but corrupted by the Notebook? Is their breakup here supposed to be a tragedy? Who knows, but doesn’t that collapsing ferris wheel in the background look awesome?

Death Nippon, interestingly, also ends on an entirely original sequence where things spiral out of Light’s control and ends with the death of his girlfriend Shiori. Naomi Misora calls L to tell him that she’s going to prove that Light Yagami is Kira, then takes Shiori hostage at the art museum and makes Shiori call Light to come meet them there. At the art museum, in front of the security cameras, Naomi insists that Light admits that he’s Kira or she’ll kill Shiori. Instead of confessing, Light begs for Shiori’s life and fidgets with a pen. They’re all distracted by the sound of sirens as the police arrive at the museum and Shiori runs, only to be shot by Naomi. Shiori dies in Light’s arms, and Naomi, horrified by what she’s done, kills herself as Light sobs helplessly over Shiori’s corpse. While Shiori and Naomi’s bodies are being taken away, Ryuk muses that Light is finally paying for his hubris, thanks to his girlfriend’s death. Only for Light to reveal that he orchestrated the whole thing.

Light manipulated every one of Naomi’s and Shiori’s, carefully laying out a sequence of events that would lead to both of their deaths, thus making him look innocent because surely, if he was Kira, he would never have let the woman he loved die. A key aspect of the plan was that guns are very rare in Japan, so by writing that Naomi would fire a warning shot and that Shiori would be hit by a stray bullet, Light could be assured that their deaths would intertwine because nobody else in the museum would have a gun. This aspect of the plan would obviously not translate well into an American adaptation, but it’s the depths of Light’s betrayal of Shiori that matters more than the specific details.

Light and Shiori’s relationship is wildly different to Light and Mia’s. Shiori never knows that Light is Kira, and their relationship is based on mutual appreciation of the law, shared interests, and tenderness expressed in their every interaction throughout the film. They never say “I love you” like Mia Sutton does, but they don’t have to—show, don’t tell, is in full effect. Their love is genuine and believable, unlike Light Turner and Mia Sutton’s sexed-up murder montages. So, Light Yagami sacrificing Shiori actually hurts and displays a much colder, deeper evil than the desperation that leads Light Turner to murder Mia. This man is the most dangerous killer in the world, and now the audience really believes that there are no lengths he won’t go to.

So, how do they compare?

Every action in Death Netflix shows confusion and a lack of forethought, both on the part of the characters and on the part of the writers. There doesn’t seem understand what a villain protagonist is; Death Netflix shoots for somewhere between anti-hero and anti-villain for Light Turner, doesn’t land on anything coherent, and the whole movie suffers as a result. Though one of Light’s last lines is a complaint that the world is not easily split into good guys and bad guys, the movie seems very intent on pushing the audience to root for Light and against pretty much everybody else.

Audience reaction to Light Yagami in Death Nippon, on the other hand, is perhaps well-mimicked by Ryuk, who responds to most of Light’s actions throughout the film with his catchphrase, a cackle of “humans are so…interesting!” At the end, however, following Shiori’s death, Ryuk is not laughing. Instead, he quietly states that Light is “worse than any Shinigami”, and it doesn’t sound like praise. Light’s complex gambits throughout the film are indeed fascinating to watch, but all of the deviations from the source material were designed to make Light’s murder of Shiori into an act of unimaginable evil. When he and L finally come face-to-face in the final shot of the movie, there’s no ambiguity about who the good guy is and who the bad guy is.

In Conclusion

The most important question, when assessing any adaptation, is why. Why this story? Why now?

In the case of Death Nippon, the answer’s pretty easy and mercenary as fuck. At the time of its release in 2006, the manga had just finished and the anime was just about to premiere. Making anything Death Note was a license to print yen, and the fast track to that sweet obsessed fandom cash was extreme faithfulness to the characters and situations that they loved. Light was made both more sympathetic and more evil, and fan-favourite Naomi Misora’s role was expanded, all in the name of purest fanservice. I’m not painting any pure artistic motives into this, but you also can’t really go wrong with a faithful adaptation of a story that was already a work of art itself.

The answer’s a bit more murky in the case of Death Netflix, but one thing that we can be sure of from how the characters were handled is that it was not made for fans of Death Note. It was made for fans of American action movies, particularly of the gore-porn variety. The key to why might be found in Adam Wingard’s comments about how Ghost In The Shell provoked “discussions” about race in western media, discussions that he doesn’t seem to have been paying attention to for him to cast Death Netflix the way he did. Did he just notice that there were discussions, but not the content? It’s possible. It’s also possible he wanted to cash in on the buzz and money generated by anime nerds excited about Ghost in the Shell, regardless of the final quality of the film. Or that he perceived Death Note‘s fame and believed it’s iconography could be replicated without a lot of prior knowledge of the franchise.

All in all, my feeling is that these movies were made for exactly opposite demographics. As an adaptation, Death Nippon is easily the more faithful and probably the superior in terms of characterization. But perhaps what Death Netflix lacks in character, it makes up for in terms of its original story and strong themes?

We’ll get to that next time, when I will have rewatched Death Netflix multiple times so you don’t have to.