We are now collectively starting to realize that Hollywood might be in a sort of inspirational crisis. We’re seeing a lot of sequels to movies and sagas started decades ago. Disney seems to be focusing more on live adaptations of its old time classics than new animated projects. Remakes are numerous, making us all sound like hipsters.

In the meantime, Hollywood started gazing outside of its national frontiers for ‘inspiration’. Ghost in Shell and Death Note might be the most famous recent examples. Somehow both of these projects brought controversy upon themselves. And yet looking further than your immediate neighborhood for inspiration can result in interesting movies. So what is the problem here?

It might be because both were adapted for the little and silver screen by their home country first. And it is those adaptations that made the stories world famous. Therefore, Hollywood appears to be cashing in on their popularity more than being excited to propose something new and daring. Simply put: Hollywood is remaking foreign movies the American way.

Not that this is new. Godzilla, New York Taxi, Just Visiting, 3 Men and a Baby, The Magnificent Seven, The Next Three Days, LOL, House of Cards, Homeland, The Ring, Funny Games, The Grudge, Possession etc., all of them are remakes of foreign movies (and this is just from the top of my head). Sometimes those remakes are great, sometimes they are bad, and sometimes they are just movies or shows. Hell sometimes Hollywood even convinces the original director to come take on the American version. It’s not even an exclusively American thing. France is happy to remake Quebecker successes. It’s just that Hollywood is doing it out of proportion.

Of the Ethics of Remaking Foreign Movies

Talking about remakes is a fashionable subject right now. It might be because we are currently drowning in ‘time remakes’. What is a ‘time remake’? Well, this is a term I have found to differentiate such films from remakes of foreign movies, which I call ‘place remakes’. And as a lot of people have said, there are three reasons that can justify a remake: making a better movie, doing something else with the same basis, and adapting it for a difference audience. A bad reason to remake a movie is when you are only doing it for the money. Unfortunately, in the case of place remakes, adapting it for a different audience might be a bad reason too.

The cultural context matters to a movie. And when you remake a foreign movie to adapt it to a different audience, you are changing this context.

Cultural Differences and How to Understand Them

To the surprise of no one, different countries have different cultures, and no one is born fluent in a foreign culture. Interacting with and understanding foreign cultures is important, and it tends to make people more tolerant. Lord knows we need more tolerance in this world. Unfortunately traveling at will isn’t really a possibility for the majority of us (there is this thing called money—complicated concept, but the important idea to comprehend about it here is that it doesn’t grow on trees).

So, your best option to discover a culture is to let it speak, and listen to what it has to say. You can absorb a lot about someone’s culture when you look at what they are creating. Books, comics, video games, TV-series, and even this great weapon of soft-power (movies)…they all have something to teach about where they come from.

Sure, you will only look at a small piece of the big picture, but it will be an honest part, even if it’s also mostly a lie. The way you lie about it to yourself is always more telling that what you might like. Bonus points if you want to learn a foreign language and you have to watch and read things made by native speakers. Trust me, I didn’t learn to speak English in the French school system.

When you remake a foreign movie, you erase the culture that birthed the story. Sometimes it can work because you have a similar dilemma present in your own culture… See the European remakes of Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis, which ‘worked’ because we all have regions that are ill-considered by other parts of our countries. But most of time, when you strip a movie or a TV series of its home culture, something gets lost in translation. Especially in the American context.

The Specificity of the American Cinema Industry

The American cinema industry is the most diverse, the richest and, to put it simply, the most powerful in the world. It produces blockbusters, period dramas, psychological thrillers, comedies, dramas, indie films, animated movie, and more. In short, the American cinema industry produces everything. If I stopped watching American movies I will, at the very least, be completely behind in term of pop culture. However if an American were to watch only their national productions they might miss the Movie of the Year™, but they wouldn’t be an cinematic outcast.

That’s why everyone having access to free entertainment has a good idea of how Americans live. On the flip side, I get the impression that the average American tends to be a bit clueless about the outside world. The expression ‘Paris and the French desert’ is never truer than when I interact with Americans. So when Hollywood remakes a foreign success to adapt it for its home audience rather than distributing the original product properly, what it is saying is not beautiful. It’s either that the original movie isn’t ‘worthy enough’ of Americans’ attention, or Americans are too stupid/self-centered to take an interest in something that is not American. No matter what the cause is, the result is that a window on the world is shut.

What’s worse is that in most cases the American product is blander than the original. It looks like every other American movie. Moreover, when the movie is a remake of an East Asian, Middle-Eastern, African, or South American movie, there’s often whitewashing that adds huge insult to injury.

In order to understand this a bit better, let’s have a look at an example.

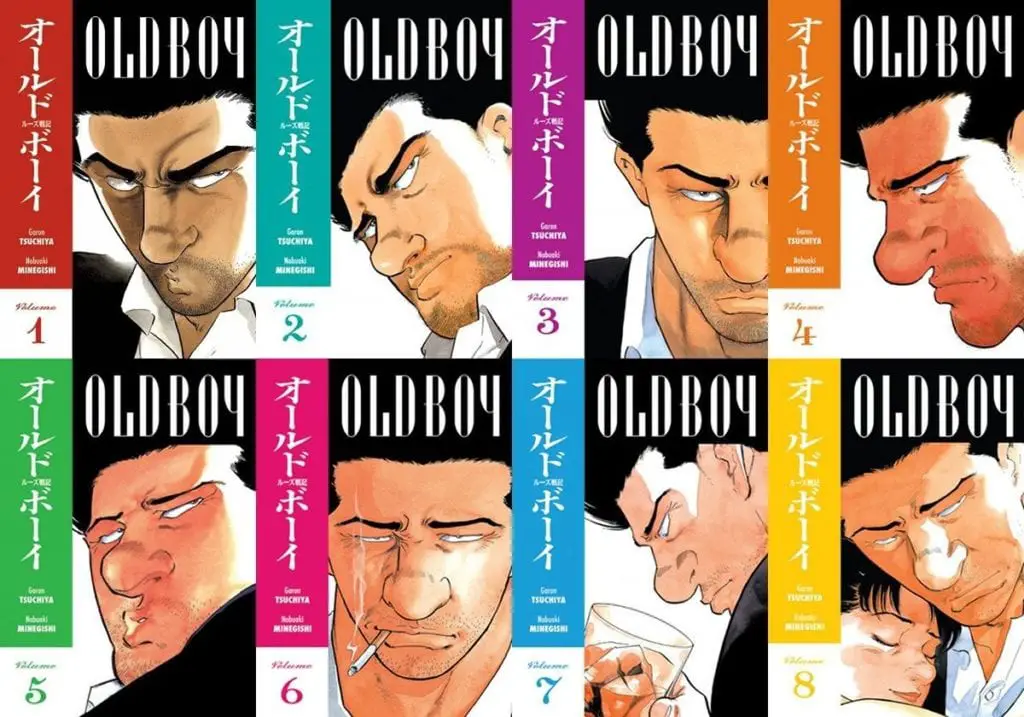

Case Study: Old Boy

Old Boy is a 2003 South Korean movie directed by Chan-Wook Park, adapted from a Japanese manga of the same name written in 1997. The film adaptation is also part of the ‘Vengeance Trilogy’ with Sympathy for Mr Vengeance and Lady Vengeance.

Old Boy is a psychological thriller following the character of Dae-su Oh, a normal man who has been held captive in an ‘hotel room’ for 15 years. During these 15 years, his wife was murdered, and he is the main suspect. His daughter was also adopted. When he is mysteriously released for apparently no reason, Dae-Su will do anything to understand who did this to him and why, and, more importantly, to get revenge.

The movie received many international awards including the ‘Grand prix du jury’ (Jury’s grand prize) at the Cannes Festival in 2004. The movie also worked fairly well in term of international distribution outside of South Korea, even if it was within its national borders that it made most of its money.

In 2013, Spike Lee ‘adapted the manga’ once again, this time for Hollywood. However this fooled no one; Spike Lee’s Oldboy can hardly be judged as anything other than a remake of Park’s Old boy. And the numerous similar-looking scenes tend to prove it (the hammer scene and the one where the protagonist is begging from the trapdoor in the ‘hotel’, for example).

Not Your Typical Remake

Quite frankly, I was surprised when I heard that the American remake was going to be directed by Spike Lee. The man doesn’t strike me as a ‘faiseur’—literally ‘maker’ in French, it is a pejorative term to refer to artists paid to make what they are told to, closer to an artisan according to our pompous definition of artist. Anyway, he appeared to me to be a serious movie director, making movies that he holds dear rather than unoriginal remakes of foreign films.

More than that, I would not have put my money on Spike Lee to white-wash a story. And yet, here we are, the original protagonist Shin’ichi Goto becomes Joe Doucett (played by Josh Brolin) under Spike Lee’s direction.

I remember when the movie was announced, the American defense was that it was a closer adaptation of the manga. I haven’t read the manga so I can’t say in term of themes (even if the themes in Oldboy do not drive the story as they do in Old Boy). However, I don’t see how you can make a ‘closer adaptation’ when you uproot a story from its original cultural context. Because even if they are not the same culture, the South Korean culture is closer to the Japanese one that the American will ever be.

In addition, I have watched both movies back to back and they look a lot like each other. Way too much for this argument to be viable. Joe Doucett even sounds closer to Oh Dae-su (the name in the Korean adaptation) than it does to Shin’ichi Goto (the character’s name in the Japanese manga). The only difference between the adaptations? Oldboy is way blander than Old Boy.

What the Movie Loses

The stories are pretty similar except for certain important details. The ending and the villain’s motivation is where I see the biggest difference between them. There is also the fact that Oh Dae-su is basically just a poor guy you can feel sorry for, whereas Joe Doucett is a full fleshed asshole. Oldboy isn’t a terrible movie, it’s just…a movie. But you can’t only be a movie when 10 years before someone told the same story using the same media and made something that will impact the audience more. Unlike Oldboy, Old Boy isn’t the kind of movie you are going to forget after seeing it.

I am also baffled by how bad the Josh Brolin’s and Sharlto Copley’s (the villain) acting looked in comparison to their earlier adaptational counterparts. It is important to note that, for American sensibilities, the acting in films from East Asian cultures can come across as ‘over-acted’. However, to my mind, Min-sik Choi (Oh Dae-se) and Yoo Ji-tae (the villain) from Old Boy gave way more interesting and more powerful performances. Their final standoff is stressful, brutal, and masterful. Brolin and Copley’s final standoff is simply disappointing. Brolin is reading his replicas and Copley is over the top. If the movie weren’t building toward this moment it wouldn’t be that much of a problem. But it is, and I don’t believe in the characters in Lee’s version.

Oldboy doesn’t take it’s time, and undermines its entire premise by doing so. In Old Boy, Oh Dae-su is mentally destroyed by his 15 years of captivity. He was isolated from all contact with anything living. His privacy and body were constantly violated. As a result, when he gets out he craves living contact to a unhealthy extent. Eating something alive and trying to rape Mido, for example, are (extremely unhealthy) ways of gaining back the sensations he missed having for 15 years. The Oh Dae-su that came out of this room was already a monster way before the finale.

In Oldboy, Doucett faced uncalled-for cruelty in his room (the mice), but not to the same degree as Oh Dae-su. Thus when Doucett gets out, he is a bit ill physically but, hey, we have no time to loose, time for revenge! In short, Doucett came out of his room as an action hero where Oh Dae-su came out a wreck of a human being.

Speaking of which, the revenge in Old Boy ultimately destroys what’s left of Oh Dae-su. At the end of the movie, he is a thoroughly broken man; he’s mute and describes himself as “worse than a beast.” Doucett, on the other hand, in falsely edgy ending, makes the most moral decision he can at that moment.

There is also the question of the fetishization of the East Asian cultures. There are zero speaking East Asian character in Lee’s version. The most important one is the bad guy’s body guard. She is your average badass Sexy Ninja LadyTM. If you compare her to her counterpart in Old Boy a male character who ends up being way more competent than her, she is just a walking cliché. This is one of those times where swapping genders actually does more damage to representation rather than less. When your original story is an East Asian one and you only include East Asian women by fetishizing them or other East Asian characters by having them work in Asian restaurants, there is a problem. A huge problem.

Suspension of Disbelief

The concept of suspension of disbelief is core to the fiction genre. It means that you accept to believe that the premise of the fictional world that is presented to you is true. More evident in fantasy (you have to believe that witch and curse exist in the Beauty and Beast universe to accept the story) it exists in every work of fiction. For example, in Les Misérables you have to agree that both the fact that all the key characters are connected and that they will find each over in Paris after a gap of twenty years is not too unrealistic.

It is a contract between the creator and their audience. “My universe works like that and you have to believe it in order for the story to work. However I promise that my story will always work by those rules”.

Once again to take an example, Tolkien’s world, like many fantasy settings, asks from you a significant suspension of disbelief. In this world wizard, elves, orcs, magic rings, and little people called hobbits exist! Yet Tolkien’s world always works with the same rules, making it easy to keep your suspension of disbelief. But if Gandalf had came to the Helm’s Deep battle with a Starbucks in one hand and an iPhone in the other you would have screamed, “What the fuck? This is so unrealistic!” (and not just because Starbucks and iPhones didn’t exist when the books were written). The suspension of disbelief would have been broken and you wouldn’t believe in the universe anymore.

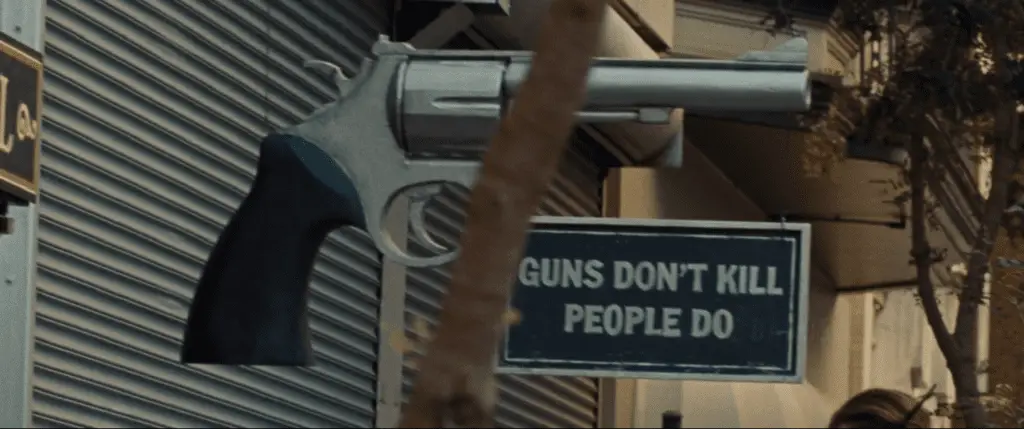

The same things happens in Oldboy. In the Korean movie, there is a masterfully done action scene in which Oh Dae-su fights against dozens of opponents with a hammer. The scene happens in Oldboy because everyone wants to have directed this scene, not because it made sense in the world the film was adapting. Doucett fights dozens of henchmen from a criminal organization. Not a single shot is fired. Actually not one of these men has a firearm… IN THE USA! Criminal organizations with no guns in the USA!? What is this dystopian world? Did Spike Lee forget that there are guns in the USA!?

What happened Spike Lee? Did you not really want to direct this movie? Because right now, I don’t believe in your story, and I don’t believe in your characters. You’re remaking a Grand prix du jury here, not some unknown little thing that wasn’t good to begin with. This is unacceptable.

Conclusion

When a powerful cinema industry like Hollywood remakes a movie, it’s never innocent and rarely respectful. Yes, it can produce good things and fun entertainment. However, the result is often too close to the original production for it to be something other than legal plagiarism. Sure, the original creators agree to it. But you have to realize how having a deal with Hollywood can change a non-American directors career. Who is going to say no to that? There’s a power imbalance there, and Hollywood and it’s directors exploit it.

When you really want to pay homage to something you thought was good, you don’t copy it. You distribute it properly so even more people can discover it. If you want to remake something without changing the core of it, you shouldn’t be in the cinema industry. You should be producing theater plays.

And for the American people who like cinema, I advise you to always have a look at the original movie in the case of a place remake. Chances are, you are going to watch a way more interesting movie as well as learn something new about a different culture and way of life. And yes, it might be less comfortable, but culture wasn’t made to be comfortable.