New year, new book! Welcome back to The Lord of the Rings re-read. I’m excited to see how The Two Towers separates itself from The Fellowship of the Ring. The latter had a clear, obvious structure as it moved along. We focused on Frodo, and the Ring, watched them journey East and then South through different set pieces, accruing allies along the way. This continued until the aptly-named “The Breaking of the Fellowship” which broke not only Frodo’s company but the narrative itself. From here on out we’re experiencing a wider story: one with multiple centers. It’s something that Tolkien must have been aware of, and it’s something that reflected in his choice to title the story the abstractly-named The Two Towers. This shift in narrative is marked by the fact that this is the first chapter in the series that is entirely devoid of hobbits.

But at the same time, we start small. No time has passed since the end of Fellowship, and the first line in “The Departure of Boromir” stresses the action and continuity: “Aragorn sped on up the hill.” The confusion that marked the Fellowship’s split is still in full effect, and the whole first chapter possesses a sense of stress and chaos before settling itself into Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli’s new mission to rescue Merry and Pippin.

Boromir’s Death

Particularly after just watching Peter Jackson’s cinematic take on the story two weeks ago, it is almost a little jarring to remember that, when readers first finished up The Fellowship of the Ring, they’d be working under the assumption that Boromir was still alive. Jackson’s staging of Boromir’s death is quite moving, and one of the best scenes in the film. It’s underpinned by the ongoing tension and rivalry between the two men, and their eventual reconciliation before Boromir’s passing. It’s hard to imagine the movie ending without it.

This is largely absent in Tolkien’s original, to the extent that Boromir’s death almost feels abrupt or unsatisfying upon first read. It can feel a bit like an afterthought as Frodo and Sam stole the spotlight of Fellowship’s climax:

“I tried to take the Ring from Frodo,” he said. “I am sorry. I have paid.” His glance strayed to the fallen enemies; twenty at least lay there. “They have gone: the Halflings: the Orcs have taken them. I think they are not dead. Orcs bound them.”

It’s more stumbling than lyrical (and, honestly, probably more in keeping with the speech of a guy who has just been pierced with a bunch of arrows and has lost a lot of blood). The stilted nature of the speech has some poetry in it, though – the short, choppy sentences that mark the first half of his speech, the implication that his death was something he deserved for having attempted to take the Ring. Even simply the fact that he already seems to be drifting, jolting back sufficiently into the present upon seeing the dead orcs to tell Aragorn that he saw the hobbits being taken away.

And it winds up being a simple, peaceful end: he urges Aragorn to go to Minas Tirith to save his people, claiming he failed them. Aragorn insists that the city will not fall, and Boromir smiles. It’s his last action in The Lord of the Rings.

Aragorn and Indecision

Boromir’s death is a nice-enough scene. But in the context of “The Departure of Boromir” his death is more in service of Aragorn’s story than his own (sorry, Boromir!).

For most of The Fellowship of the Ring – and certainly since Moria – Aragorn’s story has been one of uncertainty. He does not know the best way lead the Fellowship, he does not know whether to go to Mordor or Minas Tirith. He doesn’t know if his highest allegiance to the Quest or to Gondor. He came across most often as a frazzled, stressed-out leader, forced to make too many choices with not enough information.

Tolkien only amplifies this in “The Departure of Boromir.” Aragorn starts the chapter speeding up Amon Hen – it’s the first sentence of the book, his character is all determined action and movement as he flies up the hill after Frodo. The second paragraph, though, begins with “Aragorn hesitated.” It’s his general trajectory over the course of the chapter – leaping forward and then stopping, second-guessing.

“Aragorn hesitated. He desired to go to the high seat himself, hoping to see there something that would guide him in his perplexities; but time was pressing. Suddenly he leapt forward and ran to the summit, across the great flag-stones, and up the steps. Then sitting on the high seat he looked out. But the sun seemed darkened, and the world dim and remote.”

Nearly immediately after this, it happens again. Aragorn hears the cries of Orcs and the subsequent blowing of Boromir’s horn. Having just reached the top of the hill, he flings himself back down it. But as he moves, the thing that initially summoned him fades: “as he ran the cries came louder, but fainter now and desperately the horn was blowing. Fierce and shrill rose the yells of the Orcs, and suddenly the horn-calls ceased.”

Aragorn, being Aragorn, immediately starts to blame himself. I don’t think it’s unfair to say that Aragorn is freaking out a little bit in this chapter. He says all of these things in the course of a single page:

“It is I that I have failed. Vain was Gandalf’s trust in me. What shall I do now? Boromir has laid it on me to go to Minas Tirith, and my heart desires it: but where are the Ring and its Bearer?”

“Boromir is dead,” said Aragorn. “I am unscathed, for I was not here with him. He fell defending the hobbits, while I was away upon the hill.”

“I sent him to follow Merry and Pippin; but I did not ask if Frodo and Sam were with him: not until it was too late. All that I have done today has gone amiss.”

“But we do not know whether the Ring-bearer is with them or not,” said Aragorn. “Are we to abandon him? Must we not seek him first? An evil choice is now before us!”

Poor Aragorn. He’s spinning in on himself in an epistemological crisis like a college freshman watching The Matrix for the first time. It’s such an interesting and fitting character choice for Aragorn. While he has some leadership experience in a military context, this is one of his first times being fully in charge of a group of dependent ‘civilians.’ He seems flustered by it, nearly undone by his inability to fully know. He doesn’t have enough information: he couldn’t know to run down the hill to Boromir in time, he couldn’t know to ask about Frodo’s presence before Boromir’s death, he couldn’t know whether he ought to follow the Ring, or Merry and Pippin, or Boromir’s dying wish sending him to Gondor.

It gets bad enough that Gimli tries to snap him out of it, saying that there was no time to “ponder riddles” when Boromir’s body required attending. Unsurprisingly, this doesn’t seem satisfactory to Aragorn:

“But after that we must guess the riddles, if we are to choose his course rightly,” answered Aragorn.

“Maybe there is no right choice,” said Gimli.

And this would feel ominous, or even nihilistic, if it weren’t for what happens next.

The Departure of Boromir

“Then let us do first what we must do,” said Legolas.

Legolas and Gimli act strongly as the grounding force in this chapter. As Aragorn frets about the impossibility of knowing what to do next, they do what good friends do: they force him to focus on the moment. And so the three of them lay Boromir to rest.

Now they laid Boromir in the middle of the boat that was to bear him away. The grey hood and elven cloak they folded and placed beneath his head. They combed his long dark hair and arrayed it upon his shoulders. The golden belt of Lórien gleamed about his waist. His helm they set beside him, and across his lap they laid the cloven horn and the hilts and shards of his sword; beneath his feet they put the sword of one of his enemies.

It’s a very Tolkien-y, Anglo-Saxon-y burial. There are boats, swords, gold. But there’s something about all of this that also strikes me as therapeutic. There’s such a focus on the physical: Aragorn has spent the chapter fretting about abstract unknowables, but here he is forced to do small, tangible goods. They comb Boromir’s hair, they arrange his sword and horn. They give him a pillow for his head and they sing him a song to send him on his way.

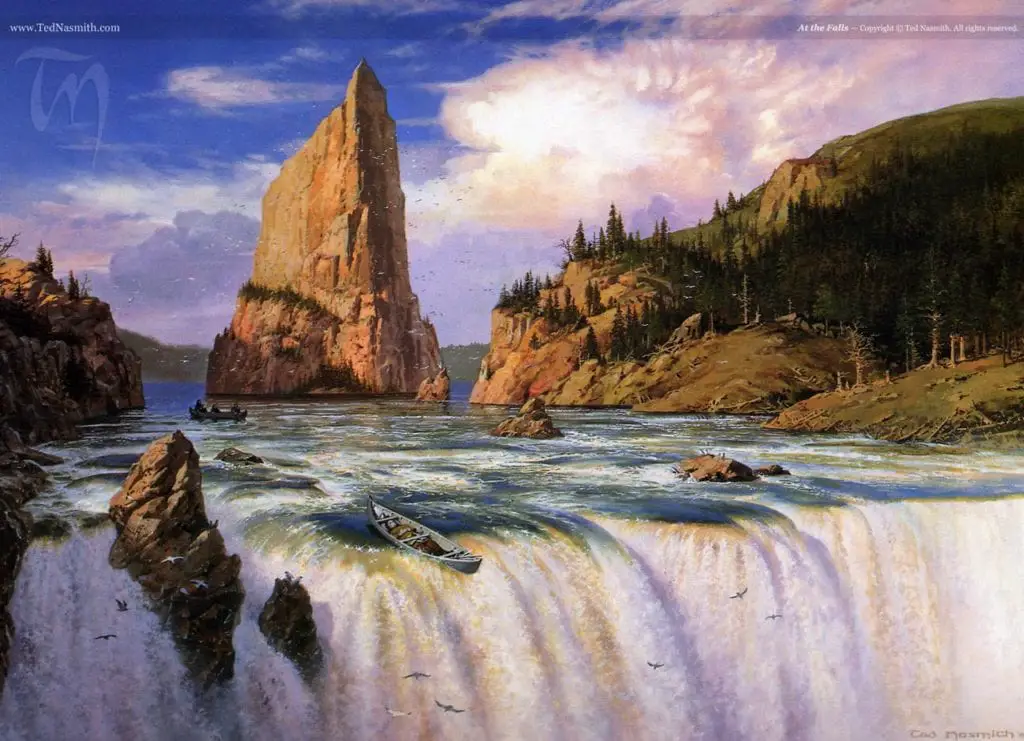

“The River had taken Boromir son of Denethor, and he was not seen again in Minas Tirith, standing as he used to stand upon the White Tower in the morning. But in Gondor in after-days it long was said that the elven-boat rode the falls and the foaming pool, and bore him down through Osgiliath, and past the many mouths of Anduin, out into the Great Sea at night under the stars.”

After this, Aragorn seems almost to be a changed man. He chooses to follow the Orcs, despite the fact that his choice had become more difficult in the interim (he learned with certainty that Frodo was not with the Orcs, and this underlined the starkness of his choice between Ring and Gondor). “My heart speaks clearly at last,” he says, “the fate of the Bearer is in my hands no longer.”

It’s entirely possibly I’m reading too much into this. But I like to think of Boromir’s funeral and its preparations as a kind of balm to Aragorn. It seems fitting to me, and it continues Tolkien’s trend of having more psychological insight into his characters than he’s often given credit for.

Final Thoughts

- This is the shortest chapter in The Two Towers and possibly the shortest in the series. I have different editions of each book, so it’s a bit hard to compare.

- Continuing his trend from The Hobbit, Tolkien continues to use narrative tricks to avoid describing combat. I feel you, buddy.

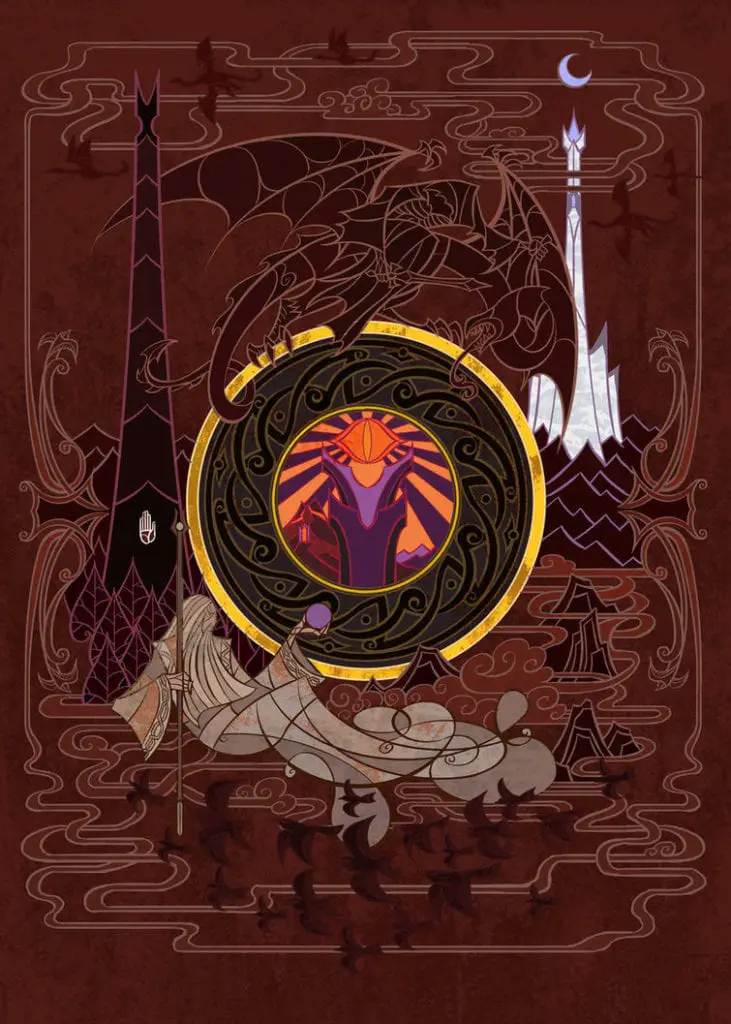

- Of Sauron: “Neither does he use his right name, nor permit it to be spelled or spoken.” This was a fun tidbit for me, and one that I hadn’t remembered. It’s an especially fun having just read A Wizard of Earthsea. It seems a fitting Tolkien-y thing to do, though as the concept of knowing a name = having power over its possessor has a long historical tradition.

- I’m very excited to read The Two Towers! It’s probably the book I remember the least clearly, the one for which the movie has colonized the most mental space. Before this re-read, if someone asked me my favorite part of Tolkien, I’d likely have answered “The Choices of Master Samwise.” We’ll see if that holds up. I’m also interested in seeing how Tolkien’s choice to simply cut the narrative in two (in respect to place rather than time) works out.

- Prose Prize: Boromir’s final in memorium is classic Tolkien and I love it: “The River had taken Boromir son of Denethor, and he was not seen again in Minas Tirith, standing as he used to stand upon the White Tower in the morning. But in Gondor in after-days it long was said that the elven-boat rode the falls and the foaming pool, and bore him down through Osgiliath, and past the many mouths of Anduin, out into the Great Sea at night under the stars.”

Art Credits: All movie stills are from Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring, courtesy of New Line Cinema. All other art, in order of appearance, comes from Miruna-Lavinia, Ted Nasmith, and Jian Guo.