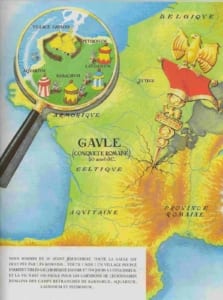

The year is 50 B.C. Gaul is entirely occupied by the Romans. Well, not entirely… One small village of indomitable Gauls still holds out against the invaders. And life is not easy for the Roman legionaries who garrison the fortified camps of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium…

The Polish version of those words has written itself into my memory when I was a child. It’s not an exaggeration to say I grew up with Asterix. But when I speak to people from across the Atlantic, it seems like the comic series is pretty obscure there, in the US, at least. A perfect opportunity for me to introduce you to it, esteemed readers.

Asterix is the work of two Frenchmen – Renee Goscinny and Albert Uderzo. Goscinny was the son of a Polish Jew and an Ukrainian woman, but he was born in Paris and grew up in Buenos Aires. Uderzo was the son of Italian immigrants. They both created in French, however – Goscinny was the writer, and Uderzo the artist.

Uderzo was the son of Italian immigrants. They both created in French, however – Goscinny was the writer, and Uderzo the artist.

The idea behind Asterix was, allegedly, to create a comic series that would compete with American cartoons, but appeal to the French history and national identity. Their choice fell to the Gauls, a Celtic tribe who once lived in what is now France.

The premise of the comic is just what the blurb above encapsulates – every book begins with it. Gaul had been conquered by Rome, but one village still resists. The brave Gauls can fight off the might of the Roman Republic (not yet empire at this point, at least technically) with the aid of a magic potion. The drink that their druid Panoramix (Getafix in some English translations) prepares grants superhuman strength. With it, the Gauls easily outmatch the long-suffering Roman legionnaires stationed in the surrounding camps.

The comic first debuted in a French-Belgian magazine, Pilote, in 1959. Its title was simply Asterix the Gaul, and it followed the titular hero as he resisted a Roman attempt to finally conquer his village. It became popular enough to eventually produce 36 books, even after Goscinny’s passing in 1977. Thirty-six books full of humour, slapstick, national stereotypes, anachronisms, puns, and gratuitous Latin sentences.

The first comic already introduces all the basic concepts of the series – the Gauls’ magic potion, the Romans’ perpetual frustration with them, and the core cast. Most notably, Asterix himself, his best friend, Obelix, and the druid Panoramix.

Even though his original design was supposedly a brawny, barbaric Gaulish warrior, Asterix is very much a trickster-hero. Panoramix’ potion gives him tremendous strength, but without it, he relies on his wits and daring. He usually plays the role of a straight man compared to Obelix, and the rest of the village.

Even though his original design was supposedly a brawny, barbaric Gaulish warrior, Asterix is very much a trickster-hero. Panoramix’ potion gives him tremendous strength, but without it, he relies on his wits and daring. He usually plays the role of a straight man compared to Obelix, and the rest of the village.

The enormous Obelix, the deuteragonist of the story, is rarely seen away from Asterix. His role in the first comic is relatively small, but from the second one forward, he shares the spotlight with the smaller Gaul almost equally. Unlike Asterix, Obelix doesn’t need to drink the magic potion to be extremely strong – he fell into a cauldron when he was a baby, so its effects are permanent on him. We’re reminded of this fact at least once every comic.

He differs from Asterix not just in size, but in personality, as well. He’s simple-minded, straightforward, and naive. His two favourite activities are fighting and  eating wild boar. But he’s always willing to follow Asterix to the newest adventure, and leave the thinking to him. His job is to carve and deliver menhirs – it’s something of a running gag that no one knows what they’re actually for. He often carries a menhir with him, using it as a weapon, battering ram, and similar purposes.

eating wild boar. But he’s always willing to follow Asterix to the newest adventure, and leave the thinking to him. His job is to carve and deliver menhirs – it’s something of a running gag that no one knows what they’re actually for. He often carries a menhir with him, using it as a weapon, battering ram, and similar purposes.

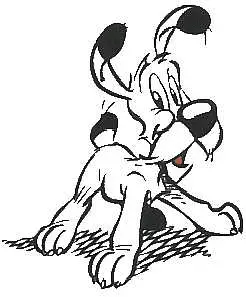

Another fixture of the main cast is Idefix (Dogmatix in English), Obelix’ tiny, white pet dog. He first appeared as a visual joke in Asterix and the Banquet. He started following the main duo as they toured the whole of Gaul (as a reference to the Tour de France bike race), never making a sound or catching the heroes’ attention. It’s only when they come back to the village that he announces his presence with a bark. The readers liked him, so Goscinny and Uderzo chose to make him Obelix’ constant companion. Idefix is a clever dog, although not as clever as Obelix thinks he is.

Another fixture of the main cast is Idefix (Dogmatix in English), Obelix’ tiny, white pet dog. He first appeared as a visual joke in Asterix and the Banquet. He started following the main duo as they toured the whole of Gaul (as a reference to the Tour de France bike race), never making a sound or catching the heroes’ attention. It’s only when they come back to the village that he announces his presence with a bark. The readers liked him, so Goscinny and Uderzo chose to make him Obelix’ constant companion. Idefix is a clever dog, although not as clever as Obelix thinks he is.

Then there’s Panoramix, the druid. His knowledge of the magic potion is what makes the comic’s premise work. He’s the only one who knows it, as it is passed on from one druid to another. As such, many plots are put in motion by his being unavailable or unable to make it, and the Romans’ various attempts to either steal the potion, or remove Panoramix from the picture. The recipe for the potion is as secret to the readers as it is to the characters – which lets Goscinny and Uderzo introduce just about anything as a necessary ingredient for it. This includes fish and petroleum.

Even aside from the potion, Panoramix is a wise and experienced man. Asterix treats him as a mentor figure, and he’s perhaps the only person the unruly Gaulish villagers actually respect and listen to.

Even aside from the potion, Panoramix is a wise and experienced man. Asterix treats him as a mentor figure, and he’s perhaps the only person the unruly Gaulish villagers actually respect and listen to.

Try as he might, the village chieftain, Abraracourcix (Vitalstatistix in English) is not such a person. He appears in the first installment, but much like the rest of the village, it takes a while for him grow into his role. He’s initially a fairly typical authority figure, who sends Asterix and Obelix off on missions. Later on, he becomes a man whose ambition greatly outweighs his actual capabilities. His villagers mostly do their own thing and occasionally pay attention to him, his wife has him under his thumb… and the two warriors who carry him around on his shield drop him with depressing regularity.

Other personages in the village include the bard, Assurancetourix (Cacofonix). He’s a dreadful singer, but entirely unaware of it. His appearances usually revolve around his trying to sing and the Gauls having none of it, though he does become more important in a few issues. It appears, sometimes, that he’s a passable musician – it’s his singing voice that scares animals. Ordralfabetix (Unhygienix) is the village’s fish merchant, whose wares are notoriously past their expiration date. But try telling him that. Cetautomatix, (Fulliautomatix), the blacksmith, most certainly does. This leads to frequent brawls (which are a popular pastime in the village in any event). Even if you’re Agecanonix (Geriatrix), whose extremely advanced age doesn’t slow him down much.

In later parts of the series, the women of the village start playing a more important role in the story. The comic is still a product of its time, though, so they mostly exist in relation to their husbands. Abraracourcix’s wife, Bonemine (Impedimenta) is the most prominent. She’s a rather typical “domineering wife”, with a short temper and grand ideas for what her husband should be, but isn’t. Not the most flattering picture.

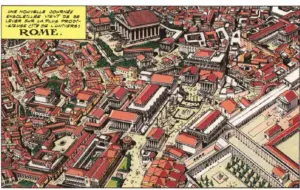

Most characters outside the Gaulish village only appear once or twice. The Roman soldiers crewing the camps change every time, and the most consistent face of Rome is Julius Caesar himself. The would-be ruler of Rome is the Gauls’ enemy, but treated with far more respect than the other Romans. Uderzo draws him much more realistically than most characters, and Goscinny writes him according to his legend, more so than history. He’s a man of honor, and keeps his word. He only rarely opposes the Gauls directly.

The would-be ruler of Rome is the Gauls’ enemy, but treated with far more respect than the other Romans. Uderzo draws him much more realistically than most characters, and Goscinny writes him according to his legend, more so than history. He’s a man of honor, and keeps his word. He only rarely opposes the Gauls directly.

However, the most frequently-recurring characters outside the Gaulish village are actually pirates. Their first entry into the series happens in Asterix the Gladiator, the fourth book. They plan to board and sack a ship Asterix and Obelix are hitching a ride on, which ends predictably. Since then, they make an appearance in most books, which usually doesn’t end well for them. If the Gauls don’t sink them, something or someone else does.

The pirates are actually a reference to Barbe Rouge, a French comic series. The three “main” members of the pirate crew – a red-bearded captain, an old peg-legged pirate, and an African lookout – are directly based on it. Of course, if anyone remembers them nowadays, it’s probably because of Asterix…

Well, that’s one colourful cast of characters. What about the stories? They’re as varied as those that appear in them. As I’ve mentioned, the plots alternate between the Gaulish village and the heroes going abroad. Many of them result from the Romans’ many attempts to finally conquer the Gauls; others have their own conflicts. Asterix and Obelix visit Lutetia (a city that preceded Paris), Germany, Rome, Greece, Spain… eventually, even North America.

The series’ humour relies a lot on exaggerated national stereotypes of the places the Gauls go to. The Britons drink hot tea with milk, and cancel everything they’re doing to drink it at five o’ clock, sharp. The Goths are obsessed with order and militaristic (their portrayal is by far the most unflattering). The Corsicans are lazy, easy to offend and capable of holding a grudge forever.

Plenty of those are anachronistic, of course. Some of the anachronisms are obvious, while others less so. People filing forms in triplicate using marble tablets, or Lutetia being an ancient reflection of modern Paris, are clear. But the series also plays fast and loose with history in other ways. For instance, when the Gauls travel to Rome, they visit the Colosseum… which wasn’t there yet in 50 BC. But how could you not include it in a comic taking place in Rome?

Aside from that, the comics’ humour is a broad variety of physical comedy, puns and wordplay. You have already seen that in the Gauls’ names. They’re not the only ones with such. Needless to say, this creates a challenge for translators. The Polish ones came out swinging. From what I’ve heard, so did the English ones.

The comics do share a measure of continuity, but they’re perfectly safe to read out of order. The first one I have read is Obelix and Co., which is the second-to-last one before Goscinny’s passing. Afterwards, I read them as I got them, which was in a fairly random order – and then I started reading a re-release, this time in order, but only those I missed the first time around. And it was fine.

Still, reading them all greatly increases the experience. The series is full if in-jokes, references and running gags. The pirates always lose their ship, a fight breaks out over fish every couple of issues, Vitalstatistix falls off his shield… and so on. Despite what you might fear, there’s no real repetition. While the premise seems one-note, Uderzo and Goscinny really did a lot of work to give each comic a unique structure and theme.

I should note that the series did not end with Goscinny’s death in 1977. Albert Uderzo, who lives to this day, kept writing and drawing on his own. The results… vary. The plots of the several comics he drew grow progressively more outlandish, with one of them involving the Gauls travelling to India, so Cacofonix’s singing can break a drought. Yes, his singing is bad enough to cause rain, apparently. Uderzo is much more prone to exaggerating characters, and resolving plots through a Deus Ex Machina.

For example, one of his albums has Asterix and Obelix travel to the Middle East and procure petroleum – which Panoramix apparently needs for the potion. While they finally succeed, Julis Caesar’s agent (a Caledonian druid Doubleohsix, who just happens to look like a young Sean Connery) spills it into the sea. Axterix returns to the village with certainty that his failure had doomed it… only to find out that the Gauls are beating off a Roman attack as usual. Panoramix had managed to replace petroleum with beet juice in the recipe. Thus rendering the entire adventure pointless.

Asterix and the Special Weapon is something of a… special case, since it’s Uderzo’s personal satire on the feminist movement. A rather crude one. I’m not sure what his intentions were, but the result isn’t good. It involves Caesar sending an all-female force of soldiers against the Gauls, confident that their chivalry won’t let them hit women. And it works. So, I’d advise skipping that one.

Still, I’d hate to end this article on such a sour note. The Asterix comics are great fun to read. If you’ve ever wanted to experience European comics from mid-20th century, they’re the perfect place to start.