I will not lie; I have a love/hate relationship with French cinema. I know all of its tropes, and I can understand and enjoy them. But if the next big thing is once again a racist comedy with Christian Clavier I swear I will become president so the CNC will never finance one of those movies ever again. If I had to recommend a French movie to you that came out during the last ten years, I would have to direct you toward movies that crashed at the box-office, like Avril and the Twisted World. Or I could simply suggest Astérix et Obélix: Mission Cléopâtre. That one came out fifteen years ago (and suddenly I feel old)… Not that there aren’t good French movies being released at present anymore. Just that I wouldn’t take the risk to spend money to cringe for an hour and a half. The risk is too big; the possible disappointment far too plausible.

Well, all of that was before I saw the trailer for Au Revoir Là-Haut while waiting for Blade Runner 2049 to start. I remember my friends’ and I’s reaction: finally a French movie that looked different. A film that actually gave me the impression that its director understood that cinema was a visual medium. So we decided on the spot that the next film we were going to see together would be this one. And we went on the 11th of November because what else could we do on the celebration of the end of World War One that watching a movie about World War One?

The Story

Au Revoir Là-Haut is the adaptation of the eponymous book written by Pierre Lemaitre. He won the Goncourt Prize with it in 2013. It follows the story of Albert Maillard, a veteran from World War One, who get entangled in the trafficking of war memorials by his friend Édouard Péricourt, another veteran but from a much higher background. To give you an idea of the irreverence of the scenario, war memorials of World War One (called ‘monuments aux morts’; in French literally meaning ‘monuments dedicated to the dead’) are in every town, in every village. In my hometown, the walls of the entrance of the town hall are engraved with the name of every man who died at the front. There is a reverence toward these monuments. There is a reverence towards World War One in France, toward what it did, what it created, what it destroyed. And maybe a fear of forgetting it.

And the movie talks about all this. But it talks about it from the point of view of the Poilus (what we called soldiers in World War One in France because they couldn’t shave in the trenches). And it talks about their confrontation with France of the early 1920’s, which wanted very much to come back to the status quo from before 1914. Even if that means forgetting and leaving behind the ones who took the hardest blows. That’s why they see the monuments dedicated to the dead as monuments dedicated to death.

World War One from French eyes

It might surprise some of you, but even if we spend a lot of time on World War One in France, very little of this time is dedicated to actual military actions. We spend more time on the societal and psychological impact of the war. That’s why most Frenchmen know about the hardship of the trenches, the dramatic changes of way of life (World War One is believed to be one of the main causes of the progression of atheism in Europe), of terms such as Gueules Cassées (literally ‘broken mouth’, a term used to designate a soldier disfigured during World War One). And the movie is focused on it.

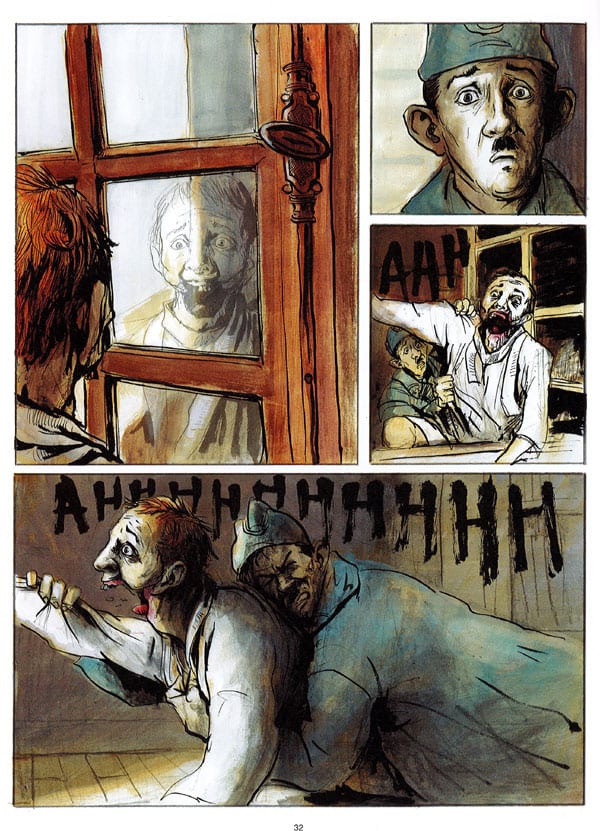

Édouard is himself a gueule cassée. His lower jaw had been smashed in an explosion while he was saving Albert. As a rich artistic young man who volunteered to piss of his father, the idea that his father might have been right added to the fact that he is permanently disfigured (to the point that he can’t even eat anymore) and a pariah to society. He lives with his friend Albert, who keeps him drugged on morphine, refusing to set foot outside.

Albert might have come physically untouched from the war but it doesn’t mean that war hasn’t taken its toll on him too. He can’t find a proper job. His fiancée left him. He has to fight crippled veterans to steal their morphine for Édouard. When asked about his time in the trenches he cries. He tries to lie, to give the official national version because deep down he is a good man who wants to do right by his country, but he can’t. So he cries.

Through the friendship uniting them we are reminded of the disaster of the war. Even when Édouard’s artistic talent brings them in this mad adventure.

A movie of the ‘little people’

Albert Dupontel, who also plays the part of Albert in the movie, has a soft spot for the ‘little people’. Through characters such as Louise, the street child who lives with Albert and Édouard, Pauline, the maid, Albert and countless secondary characters, we follow the life of ‘petite gens’ in post war Paris. How difficult it is for them. How nobody cares for them. But the movie remind us that they matter. It does it in the very last twist of the movie.

The confrontation with war profiteers, such as lieutenant Pradelle, emphasizes our solidarity toward the poor and the unimportant. Not only did Pradelle suffer nothing of the hardship of the war, he actually enjoyed it and made it worse for others. But he made a fortune by marrying well, without ever being faithful to his delightful wife, and also by scamming the state through the burial of dead soldiers. He is an awful person and he has thrived thanks to war.

Friendship and fidelity between the one destroyed by war is framed both positively and realistic. I am very fond of Albert and Édouard’s friendship. It is not always perfect, they fight badly at some points. But they care about each other. They care to the point of cheating, lying, and fighting for each other. I was delighted to see Albert kiss Édouard on the forehead and saying “it counts for the cheek” as two french close friends would.

A really well-made movie

The movie is visually stunning. At the exception of one or two effects that don’t work, the shots are beautiful, the camera movements are smart and the special effects work, during battle scenes, are more than convincing. The representation of old Paris works pretty well. And the masks… The masks! One of the first names that came during the end credits is Cécile Kretschmar. She is the artist who created the mask that Édouard starts making for himself. They are amazing. They all reflect the light differently, ‘move’ differently. They are all piece of art in themselves. A real achievement. Especially when Dupontel himself told that in order for the movie to work “it had to be beautiful”. It would be a pleasure to rewatch the movie just to have another glimpse at the masks.

I know it might sounds weird to have me expend on how beautiful and well-made the movie is. But this is so rare that a French movie leave a visual impact on me. To see a director and an artistic team having a vision of what their movie should look like and actually make something of it is not that common in France. The last time I saw a director trying to do something similar, aesthetically speaking, was for the 2014 version of Beauty and the Beast. Au Revoir Là-Haut is a treat to watch.

And it’s a treat to watch because the actors are good. Special mention to Nahuel Pérez Biscayart who can’t speak for most of the movie and has to convey every emotion through his eyes and physicality. It is a big win, especially when he starts changing his gait according to the mask he is wearing. Really a total for Nahuel Pérez Biscayart’s performance. But Laurent Lafitte is also exquisite as the villain. And no one sounds or look wrong. It is a really good and solid cast.

Finally, the tone of the movie is really interesting. For those of you who have read other articles of mine, you might have noticed that I have a certain affection for the work of Jean Giraudoux. The man had a talent to write tragedy that made you laugh while knowing full well that we are running toward catastrophe. This are the best, or the worst, way to render a tragedy. Because you get attached to the character, to their pettiness, their little courage, their humor, their humanity. Au Revoir Là-Haut is like that. It is going to end badly. But we are enjoying every step of the way.

Conclusion

If you had to see only one French movie this year may it be Au Revoir Là-Haut. It is a movie with a heart and a soul. A deeply touching movie. So if you have the chance, do yourself a favor and go see it.