We left off two weeks ago on a note of triumph, as Théoden stood tall on his saddle, rallied his troops, and as the Rohirrim spilled across the Pelennor, seeming to save Gondor from a truly rough couple of days. “The Battle of Pelennor Fields” rides the crest of this momentum in a chaotic and bracing manner, dealing out brightness and despair as Rohan’s story reaches its emotional climax.

The Battle of Pelennor Fields

The Battle of Pelennor Fields hearkens back to Tolkien’s work in The Two Towers, particularly “Helm’s Deep.” Despite his reputation for narrating battles through the eyes of hobbits who are confused and get knocked out as soon as possible, Tolkien has a knack for making battles terrifying but also tinged with a contradictory sense of beauty. Enemy scimitars look like the “glitter of stars.” The Rohirrim charge “like a firebolt in a forest.” The danger is abstract, muted and distant in the face of emotion. Of course, this doesn’t last—the arrival of the Witch-King immediately inverts this, taking beauty and poisoning it:

“It was a winged creature: if bird, then greater than all other birds, and it was naked, and neither quill not feather did it bear, and its vast pinions were as webs of hide between horned fingers, and it stank.”

Amidst this dichotomy, Tolkien continues to pull from the Old English tradition. His language feels familiar to anyone who has read Old English battle poetry, with its fondness for alliteration and metaphor. This is only accentuated by Tolkien’s tendency, once the battle has begun, to rely heavily on tangible, inanimate objects to tell his story.

“Right through the press drove Théoden, Thengels’s son, and his spear was shivered as he threw down their chieftains. Out swept his sword, and he spurred to the standard, hewed staff and bearer; and the black serpent foundered.”

Théoden’s action is focused solidly upon his spear, his sword, his standard; his enemy is abstracted to the black snake upon his banner. And this works both ways. As the arrival of the Nazgûl arrives and turns the tide on the field, Tolkien relates this to the reader by stating that Théoden’s “golden shield was dimmed.”

This, of course, is very different from how a battle scene would be conveyed in a modern story. Primacy—often for good reason—is give to the emotional weight of the battle, how its horrors are processed by those fighting it or witnessing it. There’s little internality in Tolkien’s battles. Rather, they are centered on the tangible, objects as stand-ins for the larger whole. It’s not an usual tactic in Old English poetry either—The Battle of Maldon, one of Tolkien’s faves, has similar tendencies.

Then they let fly from their hands spears file-hardened,

spears grimly ground down, bows were busy—

shields were peppered with points. (108-110)

Even moments of personal import tend towards abstraction.

Then one stern in war waded forth, heaving up his weapon,

sheltered by his shield, stepped up against Byrhtnoth.

The earl went just as resolutely to the churl,

either of them intending evil to the other.

Then the sea-warrior sent a southern spear,

that wounded the lord of warriors. (130-135).

There are things lost here, for sure. Once Théoden starts charging, the reader loses nearly all track of what he’s thinking and feeling until after the fray of battle moves away from him. But there’s a vividness to Tolkien’s battle scenes here that creates such a sense of momentum and physicality, a sort of overwhelming flurry of things that relies on the reader to fill in the rest of the gaps, carried along by the details and alliterative momentum. It’s more abstract, but done right—as Tolkien does here—it can be really thrilling.

(Take this all with a grain of salt, please, I am a soft and weak graduate student who has never known the taste of battle).

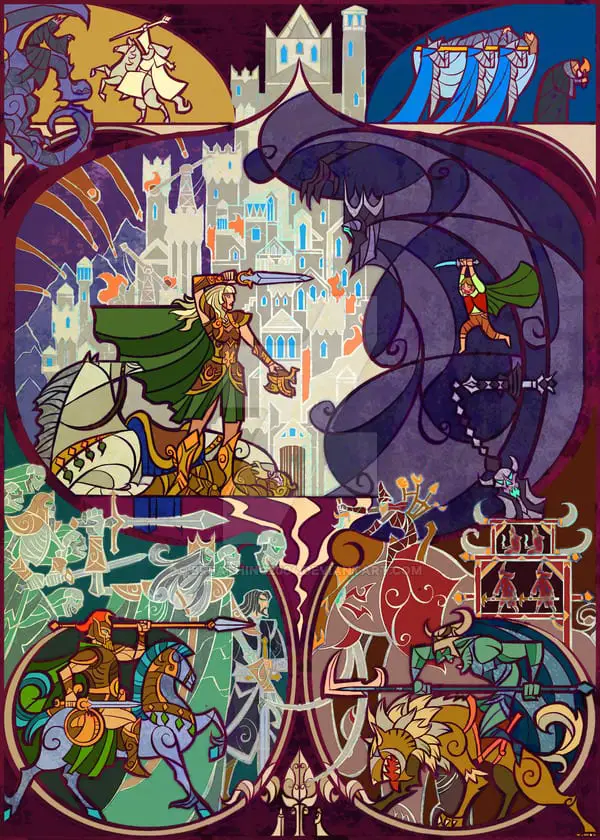

Éowyn, Merry and the Witch King

On an immediate narrative level, the Battle of Pelennor Fields serves largely as a backdrop for two main events: Éowyn and Merry’s showdown with the Witch-King and, uh, The Return of the King.

We’ve talked a lot about the hidden strengths of hobbits, the power of the under-powered in Middle-earth. Sam’s loyalty, Frodo’s resilience, Pippin’s optimism and insightfulness. They’re often soft powers, underappreciated but deeply important. Other times, Merry crawls across a devastated battlefield and stabs the Witch-King of Angmar in the back of the knee. Merry! My dude. It’s such a lovely moment for him: he’s spent so much of the last few chapters feeling worthless and in the way. Even here, in the shadow of the Nazgûl, there’s the sense that Merry still feels useless.

Merry crawled on all fours like a dazed beast, and such a horror was on him that he was blind and sick.

“King’s man! King’s man!” his heart cried within him. “You must stay by him. As a father you shall be to me, you said.” But his will made no answer, and his body shook. He dared not open his eyes or look up.

It struck me here how Merry’s heart and will stand in opposition to each other. It’s not a distinction I remember in Tolkien—so often, instead, we’ll see a challenge to the heart, and where the heart ends up, the will follows. That, of course, is where Merry eventually winds up. But the initial failure to act was interesting, and I think it ties into his bond with Éowyn. If Merry’s heart is ready but his will his shaken, Éowyn is his counterpart: all will, with a heart that’s been silenced and boxed away.

Éowyn it was, and Dernhelm also. For into Merry’s mind flashed the memory of the face that he saw at the riding from Dunharrow: the face of one that goes seeking death, having no hope. Pity filled his heart and great wonder, and suddenly the slow-kindled course of his race awoke. He clenched his hand. She should not die, so fair, so desperate! At least she should not die alone.

Éowyn has always been one of Tolkien’s stronger and more nuanced characters, and she has always been bolstered by (an understandable) bitterness and recklessness. She is hard, as Merry has seen, often angry and hopeless. On more than one occasion she talks of her death with a casual, offhanded comment. Éowyn is unique in The Lord of the Rings because in many ways she has despaired, but she’s channeled her despair—unlike Denethor, or Wormtongued-Théoden—into the fulfillment of a single, final act. The Witch-King’s threat to torture her eternally does not even make a dent. She simply laughs at him and declares:

“No living man am I! You look upon a woman. Éowyn am I, Éomund’s daughter. You stand between me and my lord and kin. Begone, if you be not deathless! For living or dark undead, I will smite you, if you touch him.”

Éowyn is very clearly on a suicide mission, aiming to go out with her father figure in a blaze of glory. Merry is horrified, hoping to help but unable to summon the will. Neither would have succeeded without the other, and it’s an especially neat narrative trick to allow Éowyn to have her (great) moment of triumph without failing to acknowledge that she’s in a… not great place right now. And it simply makes for a lovely moment, where one of the most obvious symbols of evil in Tolkien’s world are brought down by a woman and a hobbit, both flawed but trying so hard to do what they think best.

Eucatastrophes

Despite the downing of the Witch-King, the mid-point of this chapter is not one of optimism. As far as the reader knows, Théoden is dead. Éowyn is dead. Merry is bleary, traumatized, and wounded. Reinforcements are arriving on the field, and war elephants are quickly negating any advantages of the Rohirrim’s cavalry. Rain begins to fall. Éomer—seeing his sister fallen on the field—patches together a hasty, unplanned charge and flies into the fray screaming about death and the end of the world. Things look bad!

And it’s at this moment that we get the first of a handful of Return of the King eucatastrophes. Tolkien coined the term himself in “On Fairy Stories,” and it’s a very Tolkien-y term: a “good catastrophe, the sudden joyous turn” that happens in all proper fairy stories.

It is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat… giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief…. When the sudden “turn” comes we get a piercing glimpse of joy, and heart’s desire, that for a moment passes outside the frame, rends indeed the very web of story, and lets a gleam come through.”

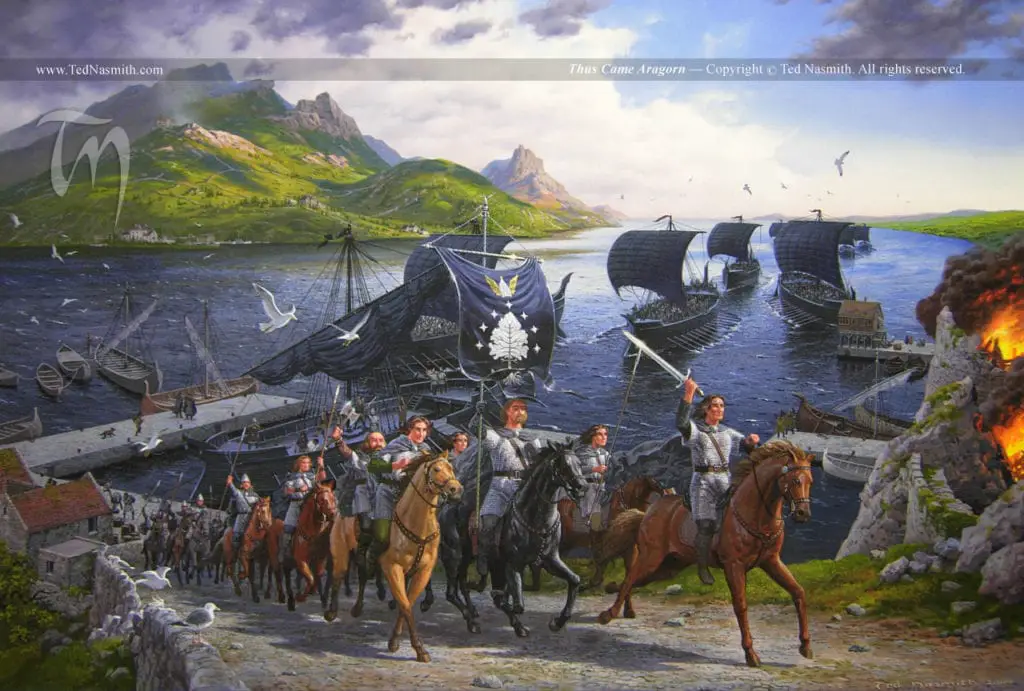

I’d argue that there aren’t really any true eucatastrophes until The Return of the King (I don’t think the end of Helm’s Deep quite reaches it, but I can understand that claim). And I don’t think that we’ll get to the most moving example of it until later on. But Éomer’s preparation for a last stand on the Pelennor, his acceptance of his fate, and then the sudden appearance of Aragorn’s standard is textbook eucatastrophe. And like last time, I like enough that I’m going to treat to a long block quote.

Stern now was Eomer’s mood, and his mind clear again. He let blow the horns to rally all men to his banner that could come thither; for he thought to make a great shield-wall at the last, and stand, and fight there on foot till all fell, and do deeds of song on the fields of Pelennor, though no man should be left in the West to remember the last King of the Mark. So he rode to a green hillock and there set his banner, and the White Horse ran rippling in the wind.

Out of dark, out of dark to the day’s rising

I came singing in the sun, sword unsheathing.

To hope’s end I rode and to heart’s breaking:

Now for wrath, now for ruin, and a red nightfall!These staves he spoke, yet he laughed as he said them. For once more lust of battle was on him; and he was still unscathed and he was young, and he was king: the lord of a fell people. And lo! even as he laughed at despair he looked out again to the black ships, and he lifted up his sword to defy them.

And then wonder took him, and a great joy; and he cast his sword up in the sunlight and sang as he caught it. And all eyes followed his gaze, and behold! upon the foremost ship a great standard broke, and the wind displayed it as she turned towards the Harlond. There flowered a White Tree, and that was for Gondor; but Seven Stars were about it, and a high crown above it, the signs of Elendil that no lord had borne for years beyond count.

Something about Éomer’s acceptance of his fate, “laughing at despair” despite his apparent knowledge of what’s to come, makes this moment so much more moving. There’s a brightness and breathlessness to the prose that works so well in conveying the moment, and makes the sudden turn exactly what you’d hope for from Tolkien’s definition: a moment to make you catch your breath, a moment of grace (religious or not) unearned but still provided. We’ll have more of this to come, and I am pumped.

Final Comments

- It was a great choice by Tolkien to have Aragorn’s arrival be witnessed by Éomer and the Rohirrim rather than telling it from their perspective. We talked in the last chapter a bit about Tolkien’s struggle with this decision but I am pretty confident it was the right one.

- I have mixed feelings about this chapter’s opening. The first paragraph gives a reminder of the Witch-King’s presence, that it was “no orc-chieftan or brigand that led the assault upon Gondor.” It sets an ominous counterpoint to the end of “The Ride of the Rohirrim,” but it also stalls out the momentum built from that chapter’s final lines. I wish the narrative focus had stuck to Théoden, giving the sudden arrival of the Witch-King more punch.

- I quite liked the last moments of the Witch-King: A cry went up into the shuddering air, and faded to a shrill wailing, passing with the wind, a voice bodiless and thin that died, and was swallowed up and was never heard again in that age of this world. It is both daunting (a reference to the past power of the king’s voice) and demeaning (“a voice bodiless and thin that died”). The last phrase is powerful until you remember that this age is ending in, like, a year or two. See you soon, buddy!

- I am very charmed by the aside on the hypothetical feelings of the maker of Merry’s Witch-King-stabbing sword. Glad would he have been to know its fate who wrought it slowly long ago in the North-Kingdom when the Dúnedain were young, and chief among their foes was the dread realm of Angmar and its sorcerer king. It’s the most Tolkien-y thing ever! I mean, it’s good, and it does highlight the scale of Merry’s actions and the historical weight of the moment. But also, it’s Tolkien taking a little battle break to talk about some sword history, as you do.

- I don’t think I have more to add at this point about Tolkien’s treatment of race, as we’ve talked about it several times. But having one of the few explicitly black groups of people in the story appear “like half-trolls with white eyes and red tongues” is a real YIKES moment, Tolkien.

- Did not know that “shiver” had the definition used a few times here – of splintering or shattering (I haven’t thought enough about the etymologies of prison shivs enough, I guess). “Shiver” as in trembling or shuddering comes from an entirely different source, apparently, But I like how well they overlap, and how the connotations of the latter add vividness to the former

- Prose Prize: There are lots of nice, stirring moments to be found here. I assumed I’d be picking something Eowyn-related, but I really enjoyed Eomer’s preparation for what he assumed was going to be his last stand.

- Contemporary to this Chapter: As we’ll see next chapter, as all this is going down Denethor is lighting his pyre. Off to the east Sam and Frodo head out of Cirith Ungol and begin their long walk to Mordor. To the north, Thranduil is fighting off the forces of Dol Goldur and Lothlórien is being attacked a second time.