With the recent anime, C-Drama and K-Pop-fueled interest in Pacific Asian cultures, it’s time for superhero comics from American companies to capitalize on current trends and feature more stories about Asians, for Asians, and by Asians. Not only will this attract new fans, but writers will be joining a literary tradition that could better accommodates superheroes than any Old West lawman or medieval knight story ever could.

Superheroes and the Chinese Xia

One of China’s major literary genres is the martial arts novel, Wuxia. Its main motifs are martial arts action, Wu, and daring feats from vigilantes, Xia. Wuxia juxtaposes gorgeous period costumes and dazzling martial arts with a poignant moral center. Most wuxia stories center around seeking some sort of justice against all odds.

The Chinese tradition of vigilante heroism finds its earliest basis in stories of assassins from the historical records of the Warring States Period. Their motives ranged from honoring the wishes of a friend to saving their nations. The greatest assassins acted with moral motives, and their willingness to take a stand against stronger opponents was more important than if they successfully killed, or even intended to kill their target.

By the time of the early Han Dynasty, there was a well-engrained tradition of influential local heroes maintaining order extra-judicially. Historical records show them benefiting their communities, but acting outside the authority of the government or the law. Their actions ranged from harboring fugitives, to donating most of their wealth to charity, to violently avenging their wronged neighbors. The Grand Historian Sima Qian praised their trustworthiness and modesty, but lamented that the label of “xia” has been appropriated by delinquents and powerbrokers. Indeed, the lines between vigilante and criminal were thin, and several of the vigilantes he documented were eventually killed for usurping the government’s authority.

However, new vigilantes continued to emerge even after government purges, and the archetype captured the Chinese imagination. Stories featuring vigilantes abounded in the Tang Dynasty, introducing the element of anonymity to wandering heroes, who hid their true names and origins. The great poet Li Bai, in his “Ode to Gallantry”, described the Xia as “killing a man in ten steps, crossing a thousand miles without stopping, departing with a wave of the sleeve once the deed is done, achievements and fame all hidden away.”

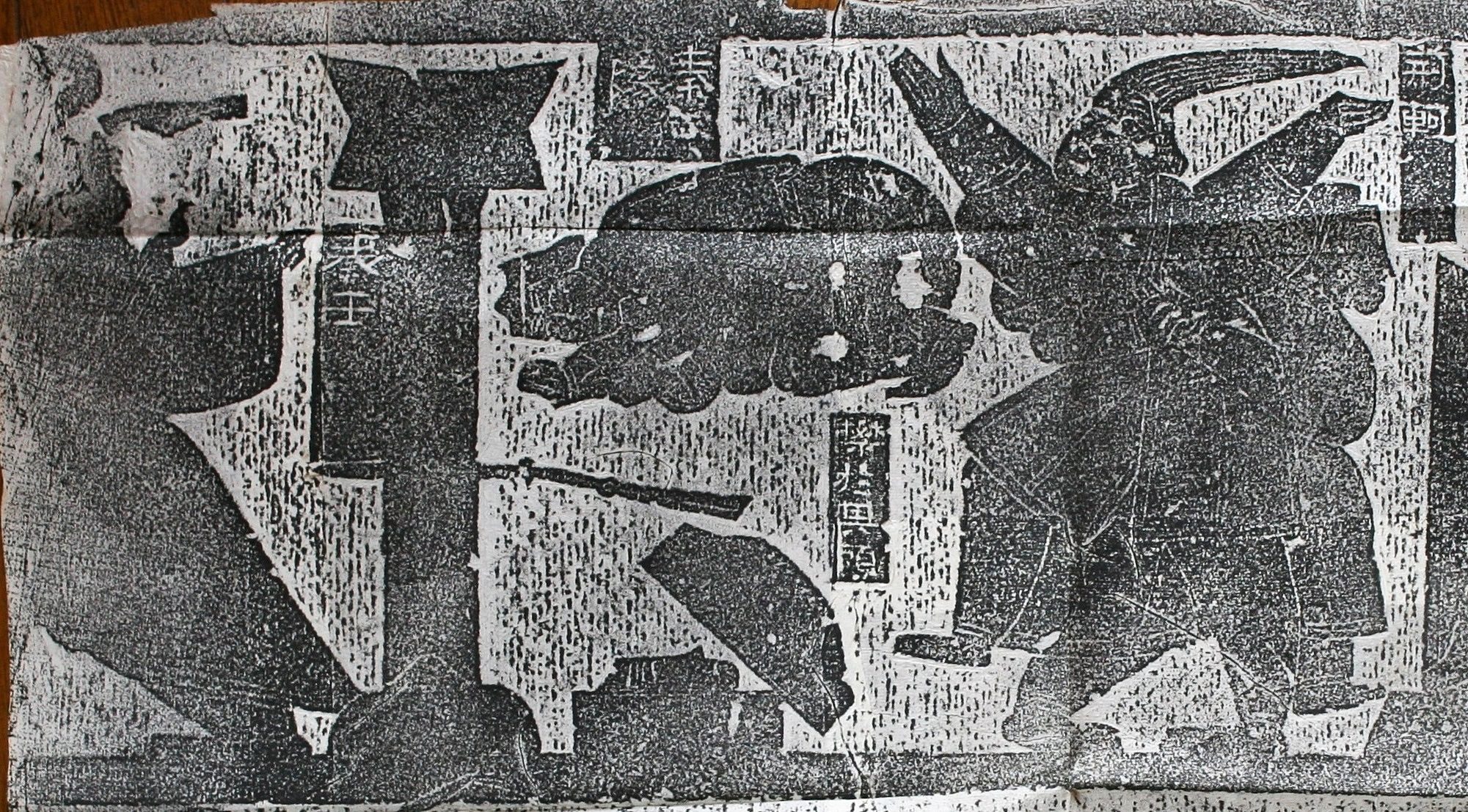

The wuxia genre continued to develop in the Song and Yuan dynasties, hitting a peak with the novel Water Margin, centered on a group of 108 chivalrous bandits. Wuxia works persisted despite multiple attempts at censorship during the Ming and Qing dynasties, and then hit a new peak post-Chinese Revolution, settling into the modern wuxia novel.

The Xia of China are not subservient to lords like the knight. Nor are they always either on the right or the wrong side of the law like the cowboy. While their activities can sometimes complement the existing social order, very often they also acted outside the letter of the law. They operate at the edge of society, occupied with menial careers like gambler, butcher, or peddler. Sometimes they are outside of society altogether, living in isolated manors which were a law unto themselves, or leading bandit gangs deep in the mountains and forests. Their activities form the Jianghu, lawless pockets existing behind and beyond civilized areas.

The Xia’s heroics are driven by personal codes of honor, as opposed to social or religious obligations. Their motives usually concern revenge, either for themselves or people being oppressed. While priests could also be vigilantes, like anyone else who received the label, they were driven by personal altruism and not religious piety.

The Xia receive no compensation for their heroism, nor would they dream of demanding any. Instead, they tend to drift into a town, solve the problems, and vanish before anyone can notice. They stand up for the little guy against both street-level hoodlums and corrupt officials, enforcing their personal sense of justice against any social or legal pressure.

The label of Xia is not contingent on the authority of a feudal class system or a lawman’s badge. Rather, it is earned by their beliefs and behavior. Male or female, old or young, anyone who does good deeds, especially of the violent kind, can be called a vigilante hero. The same individual can be a bandit or bully in one circumstance and a vigilante in another circumstance.

Another signature aspect of the Xia is their chastity. Unlike the knight who might be engaged in emotional adultery with his lord’s wife, the Xia tend to be free and unattached. Unless they are gentlemen who inherited riches from their parents, they are not shown with families. Their main relationship is the camaraderie between friends. They would “take a knife in the ribs for their comrades.” These comrades might not even be long-term acquaintances, but people they respect deeply.

As an extension of their individualized heroism, Xia would also be assigned monikers based on their talents or reputation. In more exaggerated stories, they are also capable of what a modern audience would deem to be superpowers — superspeed, super-strength, nigh-invulnerability, and occasional feats of magic.

The framework of the Wuxia story can easily be adapted to work in a superhero world, and vice versa. The world of superheroes and supervillains is its own Jianghu. Batman, Iron Man, and other adventurers of the gentleman hero mold could easily be found in a mountainside martial artist manor. The Punisher would be the grim avenger strolling into town and violently massacring the local tyrants. Street-side heroes like Luke Cage, the Question, Green Arrow, Black Canary, and the Flash are all heroes who stand up for the common folk. Spider-Man, Hulk and Catwoman are the tough guy vigilantes, doubted by the peaceful public and always hovering in a legal gray zone.

Superheroes and the Japanese Yojimbo

In Japan, the superhero counterpart is the Yojimbo, a ronin hired to protect a person, establishment, or town. Like the Xia of China, their archetype is inspired by roving swordsmen, martial artists, and preachers, simultaneously dangerous and admirable figures for the common crowd.

During the chaotic Sengoku era, the rigid top-down Confucian social order shattered, bringing in a might-makes-right era of social mobility and personal glory, but also nihilism and rebellion. Discontent youths dressed in outrageous fashions, peppered their speech with vulgar slang, and engaged in scandalous or reckless antics. They were called Kabuki-mono, the “crazy ones.” By the early Tokugawa period, they split into the rival gangs of Hatamoto-yakko, thugs from the samurai class, and Machi-yakko, townspeople and their hired guards organized into militias. Like the earlier vigilantes of China, they were subject to brutal government crackdowns until they mostly disappeared as an institution.

However, while the eccentrically dressed gangsters disappeared, their stories didn’t. Kabuki theater thrilled the Tokugawa-era audience with stories of extra-legal heroism. Some were implacable avengers, others were charitable thieves, or merely brave folks extending a hand to their fellow men in times of need. Kamakura Gongorou, Ishikawa Goeman, and Banzuiin Chobei were some well-known heroes, displayed to the audience in splendid, flamboyant costumes.

The Yojimbo holds true to a code of personal honor. Like the Xia, they are not involved with lords or law enforcement. They fight for justice sometimes because they’re paid to do so, but usually because they want to. Like the superhero, justice is not just a job for them. They hail from the underbelly of society, with no government approval for their actions.

Already outsiders because they wander from community to community, their morality also sets them apart from both settled people and fellow rogues. The Xia had comrades who assisted them, but while the Yojimbo could be a part of a criminal group, more than often they faced climactic confrontations alone, or only with the assistance of those they protected.

Like the European knight and unlike the Chinese Xia, the Yojimbo technically belongs to the ruling warrior class. However, they are outcasts of that class, possessing the same freedom and loneliness of the American cowboy. While they are consumed by the same moral conflict of obligation versus personal feelings as legitimate samurai, their dilemmas are more relatable for a working-class audience. They are rebellious, against custom, against authority, and sometimes against their own employers if their morals don’t align. They are cathartic heroes, providing quick and violent solutions for familiar problems.

The framework of the wandering Yojimbo had been adapted for both Japanese henshin hero shows and American Westerns, all focusing on lonely protagonists. Loneliness is a reality for superheroes as well. Their morals and hidden identities set them apart from others in their community. Very often they mark out their own specific turf and protect it, both against supervillains and other superheroes. Street-side heroes serve as bodyguards for their communities, or as in the case of the X-Men, for entire minority populations. Cosmic heroes like Green Lantern wander far and wide in search of work. There’s even superheroes for hire with hidden hearts of gold under their mercenary facades. All these archetypes invite comparisons to the Yojimbo.

How Superhero Comics Could Improve

Despite all the parallels between modern superheroes and traditional Asian vigilantes, there are still woefully few Asian superheroes. Most are side characters or legacies, with few holding solo titles. This problem should be addressed, especially since Asian media now holds international appeal.

Writers do themselves a disservice if they attempt to cram superheroes into standard heroic archetypes of knight or sheriff. Rather, they should embrace the outcast vigilantes of Asia, and in the process, introduce Asian heroes to bridge the gap between Wuxia, Yojimbo, and the modern superhero. Using the archetype of the Asian vigilante will allow the superhero genre to flourish in a more organic setting. It will also tap into the rebellious side of the superhero, as opposed to portraying them as conservative defenders of the current order.

The audience for Asian settings and Asian protagonists already exists, as does the framework to tell Asian superhero stories. It’s up to writers to tap into it.

Images courtesy of Central Motion Pictures and Kurosawa Production

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind

you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in

the conversation!