Tolkien likes borders. I suppose you have to like them, as a fantasy author, otherwise you’d never find the patience to draw up the map. You’d swiftly become bored with all those stories about people who step through an gate in the wood and fall into Faerie, or people who pay the toll to take a ferry across a river and end up in a different world.

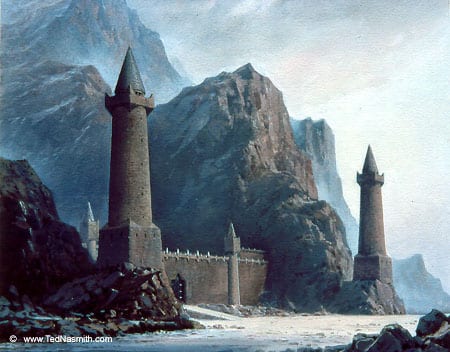

Crossing a border happens often in The Lord of the Rings: Sam leaving The Shire for the first time, the hobbits going under the hedge in Buckland to enter into the Old Forest, the crossing the Celebrant to reach Lothlórien, and even Aragorn and Company simply first crossing over into Rohan. This seems to be what’s going to happen again here, as our group approaches the Black Gate. The first sentence of the chapter states that “before the next day dawned their journey to Mordor was over.” It’s… not, quite, and you could argue that a lot of this chapter rehashes what came before. However, the arrival at the Black Gate serves as an emotional fulcrum for both Frodo and Gollum, prompting decisions that shape the rest of the narrative.

Frodo at the Black Gate

“I did,” said Frodo. His face was grim and set, but resolute. He was filthy, haggard, and pinched with weariness, but he cowered no longer, and his eyes were clear. “I said so, because I purpose to enter Mordor, and I know no other way. Therefore I shall go this way. I do no ask anyone to come with me.”

This is the first time Frodo speaks in “The Black Gate Opens,” and it’s startling. It’s a big step away from his behavior in the marshes where he was near silent, dragged down by the weight of his burden and increasingly aware of a deadly gaze ready to pin him to the spot. It’s nice to see Frodo suffering less. At the same time, his new attitude isn’t derived from hope but the realization that his quest is finally over. “I am commanded to go to the land of Mordor, and therefore I shall go,” says Frodo. “If there is only one way, then I shall take it. What comes after must come.” It’s a resoluteness built on certainty, a certainty built on inevitability.

His renewed clarity stems from the fact that Frodo believes he’s reached the point where there aren’t any more choices to make. He’ll try to get through the Black Gate. If he does, he does. Then he’ll take it from there. It’s something that Sam realizes immediately and – like last chapter – does not try to talk him out of, or provide him with any false hope:

Sam said nothing. The look on Frodo’s face was enough for him; he knew that words of his were useless. And after all he never had any real hope in the affair from the beginning; but being a cheerful hobbit he had not needed hope, as long as despair could be postponed. Now they were come to the bitter end. But he had stuck to his master all this way; that was what he had chiefly come for, and he would still stick to him.

Frodo’s Choice

Of course, Frodo isn’t given much time to relax with his clarity of mind . Sméagol/Gollum provides him with another choice, as impossible as all the rest. Throughout his journey, Frodo has been remarkably light on the self-pity (no joke, guys, I would have felt sorry for myself every single step). He slides close to it here, wondering why Gandalf’s guidance and advice had been taken from him so early. But he never sinks into it. He comes to the conclusion that it’s not a choice with a right answer, a choice that anyone could make based on wisdom and sound judgement. It’s simply a choice.

And here he was a little halfling from the Shire, a simple hobbit of the quiet countryside, expected to find a way where the great ones could not go, or dared not go. It was an evil fate. But he had taken it on himself in the far-off spring of another year, so remote now that it was like a chapter in a story of the world’s youth, when the Trees of Silver and Gold were still in bloom. This was an evil choice. Which way should he choose? And if both led to terror and death, what good lay in choice?

We never get a direct insight into how Frodo makes his choice. It’s interesting though that he chooses to follow Gollum’s ominous-sounding path right after witnessing Sam sing about oliphaunts, and then talk about them with Sméagol. It’s also interesting that Frodo frees himself from indecision with a laugh—right around the time that, off to the west, Gandalf laughs to free himself from the vestiges of Saruman’s voice.

It’s never stated explicitly, but it’s hard for me to read this section and interpret Frodo as choosing the more hopeful path. I mean, it’s not that hopeful – Gollum is being openly shady in his description of it, and his answer to whether his secret path was guarded is to ignore the question and until finally doing the equivalent of throwing up is hands and yelling, “yeah, PROBABLY.” Attempting to infiltrate the Black Gate would be a suicide mission. In turning away from it with a laugh, Frodo is embracing the reality of having to endure more pain and uncertainty for the improbable hope that it will lead to a better end.

Gollum at the Black Gate

Gollum, of course, is in the inverse situation. While Frodo for a moment seems to be free from further choice, Gollum’s choice becomes impossible to postpone. He fears the Ring falling into the hands of Sauron at least as much as Frodo does, and he fears it more viscerally. “Don’t take the Precious to Him!” he says. “He’ll eat us all, if He gets it, eat all the world.” It’s interesting to see here, too, that Gollum bestows Important Capital Letters not only on the Ring, but also on Sauron. He’s standing right on the border with the land where he underwent what we can assume was some terrible trauma (at one point he says that Sauron’s hand only has four fingers, but “they are enough”). He doesn’t want the Ring to return to it, and he has only a final chance to stop it.

Gollum’s first attempts to do so are rather pitiful. Before he suggests Cirith Ungol as an option, he makes the vague, half-hearted suggestion that Frodo simply give the Ring to him, and go away to “nice places” and not worry about it anymore. Even Gollum doesn’t seem fully convinced that it will work. He only has one real path to take (as Frodo assumes he himself does), but he doesn’t yet want to do it. He doesn’t want to send his master into a spider cave and doesn’t want him to be endangered. So he tries something else, a nebulous, unconvincing proposal to just adopt the Ring and let everyone live happily ever after. But when Frodo states resolutely that he will go into Mordor with it, no matter what, Gollum panics and admits that there is “another way” (another, orc-and-spider-filled way). It was where his choice was heading from the start.

You Will Never Get it Back

When Gollum offers up this choice, things go mentally downhill rather quickly for him. At first he gets a stern warning from Good Cop Frodo (even Bad Cop Sam is approving of his style):

“Already you are being twisted. You revealed yourself to me just now, foolishly. Give it back to Sméagol, you said. Do not say that again. Do not let that thought grow in you! You will never get it back. But the desire may betray you to a bitter end. You will never get it back.”

Frodo then goes on to promise that if Gollum were to try to take the Ring, Frodo would put it on and use it first (in a close foreshadowing of the actual end of “Mount Doom”). It’s an awful moment for Gollum, and he collapses into an “abashed and terrified” mess. It’s hard to know if it’s because of Frodo’s closing threat or the stark repetition: “You will never get it back.” The speech is a telling moment for Frodo as well. As far as I can remember, this is Frodo’s first suggestion that he would be willing to put on the Ring and to use it against someone else. It’s hard for me to tell at this point how much of a hold it has over Frodo, which is part of what makes this moment so frightening. It’s hard to know how much of his speech to Gollum comes from personal experience (the sense of being twisted, perhaps) or from his own fears (you will never get it back).

The Easterlings

Now for a somewhat off-topic discussion. While The Lord of the Rings has not been maliciously racist, “The Black Gate Opens” continues the trend of unfortunate racial connotations. I’m not convinced that Sauron’s supporters marching into Mordor are designed to be any particular ethnic group, but they do read like an amalgamation of traits that a white Englishman in the early 20th century would use to describe non-Europeans.

“They have black eyes, and long black hair, and gold rings in their ears; yes, lots of beautiful gold. And some have red paint on their cheeks, and red cloaks; and their flags are red, and the tips of their spears; and they have round shields, yellow and black, with big spikes. Not nice; very cruel, wicked men they look.”

That’s not great, and at best it’s a rather orientalist view of foreignness. At worst, we’re left with the notion that one of the very few non-European peoples in the story were either (a) dim enough to being unquestioningly duped by Sauron, (b) too weak to mount a resistance, or (c) totally on board with Sauron’s whole vibe.

This would be less a problem, of course, had Tolkien not associated most of his heroes with whiteness and fairness. Hobbits are perhaps an exception. As far as I recall hobbit skin tone is only related to the reader as various shades of brown, and the hobbits with the darker skin are described as far more numerous. But even in that scenario, we run into problems. Frodo, for example, is frequently described as being fairer than most of his hobbit brethren. His fairness also tends to be correlated to an inner nobility and moral strength. It’s a relatively small part of Tolkien’s overall thought, I’d say, but an unfortunate one.

Final Comments

- Gollum’s insistence that he did escape from Mordor on his own was very sad, to me. “I did escape, all by my poor self. Indeed I was told to seek for the Precious; and I have searched and searched, of course I have. But not for the Black One. The Precious was ours, it was mine, I tell you. I did escape.” While I’m sure it was not intended this way at all by Frodo and Sam – the questions they were asking were important ones to ask – Gollum seems to have interpreted it as an attack on his agency in escaping a place he views with deep-seated fear.

- This chapter is particularly adept with the foreshadowing. When Frodo is disappointed to discover that it’s not Gondor marching on the Black Gate, he compares the imaginary soldiers as “risen like avenging ghosts from the graves of valor long passed away.” We have quite a few chapters to go until Aragorn reaches the Paths of the Dead, but chronologically it’s only about two days away.

- Frodo’s reference to the Trees of Silver and Gold (Laurelin and Telperion) is another nice reference. Additonally, Shelob—whose unstated presence hovers over this chapter—is the last descendant of Ungoliant, the spider-darkness-monster (?) that destroyed the two trees.

- Sméagol’s insistence that he doesn’t want oliphaunts to even exist again walks the funny/sad line well. “No, no oliphaunts,” said Gollum. “Sméagol has not heard of them. He does not want to see them. He does not want them to be.” Poor Sméagol has been having a tough time, so I can understand not wanting to have to deal with war elephants, but the extent to which he escalates things made me laugh a little.

- I loved this: “He said: we’ll go to the Gate, and then we’ll see. And we do see. O yes, my precious, we do see. Sméagol knew hobbits could not go this way. O yes, Sméagol knew.”

“Then what the plague did you bring us here for?” said Sam.

Never change, Sam. - Prose Prize: It had always been a notion of his that the kindness of dear Mr. Frodo was of such a high degree that it must imply a fair measure of blindness. I like this so much, both as a sentence and with the following acknowledgment that kindness isn’t the equivalent of naivete.

- Tolkien’s Wanton Cruelty to Innocent Punctuation Marks (sponsored by Mytly): A tough inaugural chapter all things considered. There are boatloads of semicolons, but I wasn’t able to catch any of the rarer three-in-one-sentence uses. At one point he uses a semicolon in three of four consecutive sentences. If we expand our scope, though, to Tolkien’s general language brutality, a clear winner emerges. Tolkien’s use of “amidmost” on the first page of the chapter, to designate the Sea of Nurnen that is presumably… most amid Mordor, is something that I both hate and love. Calm down, J.R.R.

- Contemporary to this Chapter: Tolkien was kind enough to build this one in for me! Thanks, buddy! As noted in the chapter, Gandalf and the Fellowship 2.0 are speaking to Saruman at Isengard. And Pippin’s palms are starting to get itchy.

- Guys, it’s almost Faramir time.