Bollywood’s representation of the Mughal Era (16th to 17th century) tawaif has ranged from sympathetic to disparaging. This article is an adaptation of a longer paper that I wrote years ago for a class on courtesans and presented at a conference.

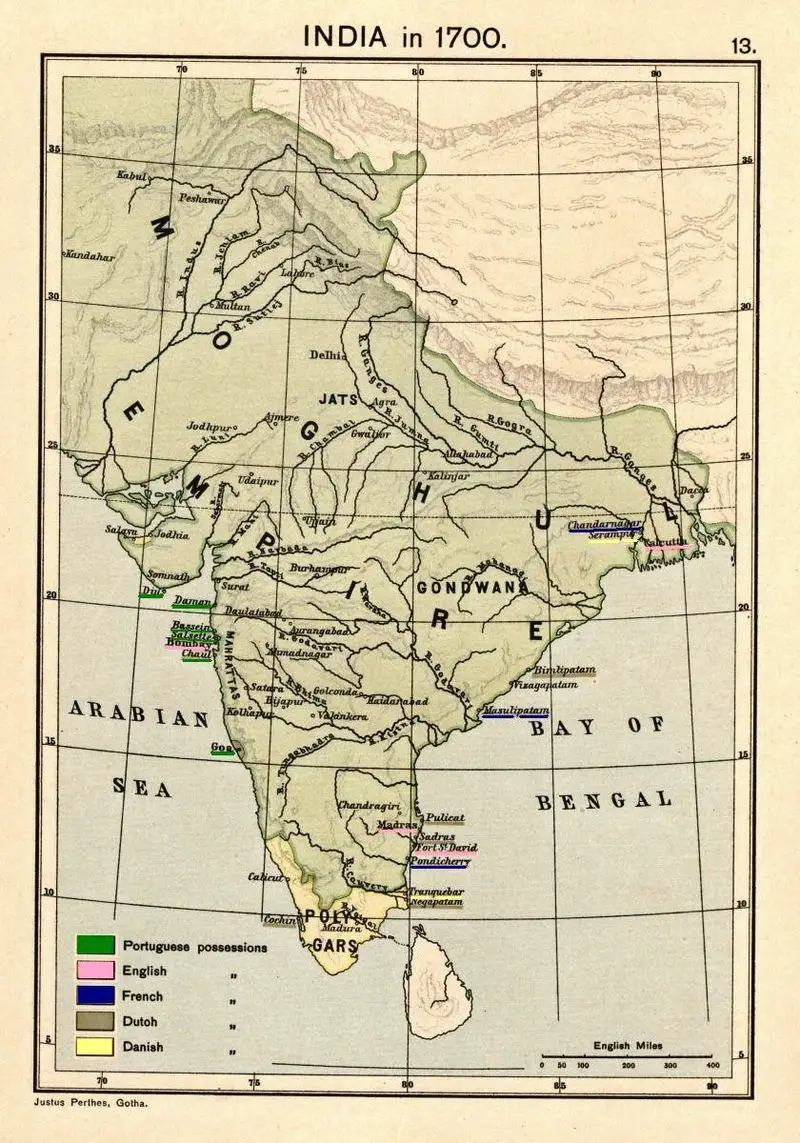

The tawaif were elite courtesans under Islamic rule, and the term tawaif (from Urdu) comes from “tawaaf,” referencing a pilgrims’ circumambulation of the Kaaba, representing their circular movement around the entertainment space. Tawaif were professional performing artists who catered to the nobility of South Asia, particularly during the Mughal Era. By the end of the 19th and into the 20th century tawaif were fading in importance due to British colonialism and imposition of those cultural values.

During the height of tawaif’s popularity in the 17th and 18th centuries, they were respected by their patrons for their talent and skill. Their performances were rewarded with payments and gifts and thus many were often very wealthy. That the tawaifs’ work was witnessed and patronized by the highest nobility in the exclusive yet public space of the court set them apart from others. At the height of their popularity, the tawaif were some of the most elite professional performers.

They had extensive knowledge of dance, particularly the kathak style, which originated from the nomadic bards of ancient northern India. Its current form contains traces of temple and ritual movement and is meant to tell a story through dance. The kathak dances performed by the tawaif were of the expressive kind, as the audience would see the dancers’ facial expressions. This style allowed the tawaif to entice the audience and connect while telling their stories through dance.

Tawaif also learned vocal forms of music such as classical Hindustani, ghazals, thumri, and instrumental music utilizing traditional Indian instruments. Ghazals are a poetic form consisting of a series of rhyming couplets and a refrain that spread into South Asia in the 12th century by Sufi mystics. The ghazal traditionally deals with illicit, unattainable love and can also encompass love for a higher being in the Islamic mystic context.

As men were not supposed to marry courtesans, this vocalization of the desire for illicit love fit the situation perfectly. Thumri were romantic songs and the tawaif displayed her body and emotions during the performance to be consumed by the audience directly during a thumri.

She showed off her poetic, musical, and literal skills in mehfils, which were gatherings held in kothas or the homes of the noblemen. Tawaif were hired to dance a mujra which is a combination of the native classical kathak dance with music and song such as the thumri or ghazal.

Tawaifs were known by their high quality costumes and cosmetics in these performances. For example, during kathak dances, the tawaif usually wore ghungroo (bells) on their ankles. Except for saris which showed the midriff, most of the anarkalis covered their full body.

Despite their popularity, the tawaif occupied an ambiguous social state. They were women in a patriarchal society who appeared before men unveiled like wives or nobility. As solo performers and vocalists, they claimed an important status in the hierarchy of musicians and at court. Though they usually did not marry, many had relationships which were long lasting and warm.

British Colonialism and Dispossession

After 1857, the British began to enact policies to deal with their Indian empire including the problem of the noblemen having many wives and tax free lands. Many tawaif lost their land because they were not of noble birth, leading them to become dispossessed and forced to return to their old profession in a Lucknow where patronage had shrunk considerably.

These women were usually retired and under the protection of their old patronage. Prior to 1857, relationships between British men and Indian women were not uncommon or frowned upon but the new British policy aimed at maintaining a distance between the rulers and the natives.

Worse, the Lal Bazaars were created in the margins of the cantonments where the British soldiers could go to fulfill their sexual needs, and the laws the British instituted redefined tawaif as simple (and not liked) prostitutes, forcing them to adapt that role.

By the 1890s, though the tawaif were still performing, even Indians were writing strongly-worded letters to newspapers, holding meetings, or sending memorials to the Viceroys to stop the performances of “indecent dances.” Unsurprisingly, the same bourgeoisie which had spearheaded the destruction of the institution of the tawaif appropriated their arts and now dance is an upper middle-class phenomenon. Representation of the tawaif in writing thus became sensationalist and apologetic.

For example, Mirza Mohammad Ruswa’s Umrao Jaan of 1905 is written so that Umrao is the reluctant tawaif who finds herself in the kotha as a result of a kidnapping. She is thus not responsible for her life and work, but instead is the victim of her circumstances.

As with other courtesan cultures and related sex work groups, there are people who were trafficked into the work or sought it as a last resort, but by suggesting that those were the only stories, those who chose to be tawaif and enjoyed their work are seen as the anomaly. Therefore, such literary representations of tawaif who were down on their luck and the courtesan with the heart of gold become common themes in film as well.

Courtesans and Sex Workers With Hearts of Gold

Contemporary era films post 2000 portray sex workers with hearts of gold and/or having to rise above hardship. In these films, sex workers are any of the women who make their money or living through sexual acts with men, whether because of the monetary necessity or out of their own will.

In 2004, Kareena Kapoor appears as a sex worker playing a role in which she inspires the hero to live life again after tragedy in Chameli. Likewise the following year, Sushmita Sen must avenge her lover’s death and kill the priest who abused her in Chingaari.

Rani Mukherji portrayed both a sex worker who falls in love with the hero of Saawariya and a sex worker down on her luck in Laaga Chunari Mein Daag both released in 2007. She does not marry in the first film, but in the second finds out that her partner has known all along of her work, loves her still, and they marry at the end. All four characters make a better life for themselves and are portrayed as good women.

Kapoor in Chameli

Mukherji in Saawariya

Tawaif in Films

In films about tawaif, a frequent theme is that the tawaif attempts to become a respectable woman based on patriarchal norms. Even the strategies by which the hero might gain control of a heroine like show of wealth or power or gaining the parents’ approval are not available.

Control over the courtesan involves economic exchange, criminality, or violence instead of a romantic relationship and the women must ascend to an acceptable status by linking to another man. Such representations highlight the contradictions within films about tawaif because by their nature, tawaif are women without solid or socially acceptable connections to men.

Within the constructions of heroine behavior and norms, characters in tawaif films are presented on a spectrum of positive and heroine-like portrayals no matter how distressing the outcome.

Rekha is an example of this spectrum through her own portrayals of courtesans. In Muqaddar ka Sikandar (1978), Zohra falls in love with the hero and then kills herself when she finds herself unable to stop his entry into the kotha. In 1981, she portrayed Umrao Jaan in the adaptation of the novel and, after attempting to find love, her character ends up alone with nothing but her profession.

In 1989 Kasam Suhaag Ki, she portrays a courtesan kidnapped at a young age and forced into courtesanship, faces trials of love and danger, and ends the film in her mother’s arms, dead from a gunshot wound. These are only three of many portrayals as courtesans in Rekha’s filmography. While these examples have unhappy endings, they exemplify the tawaifs’ desire to ascend into the role of a respectable women as established by the male gaze.

Becoming a respectable woman through often secret heredity is another common theme in Bollywood. In Pakeezah of 1972, Meena Kumari portrayed Shahibjaan who in the final scenes of the film is revealed to be the daughter of the main hero’s paternal uncle. In Khilona of 1970, Mumtaz plays Chand, a courtesan who is hired to help the hero become happy again after an attempted suicide.

At the end, it is revealed that she was actually born into a noble family which allows the extended cast and the hero’s family to accept her into the fold. Here, the only way that the tawaif becomes acceptable to the other characters as a whole are through their links to men who are respectable because of their proper lineages.

Not all tawaif are accepted, however. In both Mughal-E-Azam of 1960 and the 2002 adaptation of Devdas, both women are not accepted, despite their links to men of high stature. Madhubala has a relationship with the son of the emperor but by the film’s end lives in hiding with her mother.

In Devdas, Madhuri portrays the courtesan Chandramukhi who attempts with all her strength to convince Shahrukh Khan’s Dev to stop drinking. He is suffering from the loss of his love, Paro (played by Ashwarya Rai), forbidden to see him.

Rai would go onto portray Umrao in 2006.

Below is one of the best performances of traditional dance by Dixit and Rai, well ever.

As the relationships develops, Dev falls in love with Chandramukhi and she tries to stop his alcoholic behavior. She typifies the courtesan with the heart of gold and at the end of the film, none of the three main characters get a happy ending. Dev dies from drinking, Paro is not allowed out of her house, and Chandramukhi is left without her love or a friend. This type of unhappy ending for the tawaif is most common.

Such representation of unhappy endings contradicts how the tawaif probably would have been during the height of their popularity. The films are actually more indicative of what was likely the reality after the British began their colonization of India.

Conversely to movies centering the tawaif, courtesan, or sex worker, item songs provide these same women much more agency!

Bollywood Item Songs and Heroine Expectations

Anyone who watches Bollywood is familiar with item songs. Catchy and upbeat, they’re characterized by their usual lack of connection to the film in which they appear in, and as a way to showcase beautiful dancing women (and men). Recently they’ve become the movie’s “theme” song and are shown at the end prior to or over the credits. Hrithik Roshan’s Bang Bang is one such example.

From the very start of Indian cinema in the 1930s, heroines only danced when the hero was present either as a spectator or as a participant. The interjection of the vamp character (usually as a cameo role) in an item song allowed for some inappropriateness in a film in a way that worked around censorship rules until the roles began to merge. Until the 1970s the item song focused on the “vamp” who could wear revealing clothes and sang boldly. The vamp and heroine then merged into one figure in the 1980s.

This transition ultimately marked the increased social acceptance of sexually explicit dancing for the morally respected heroine. Mujra scenes contrasted with those of standard item songs and it was not until the 1990s that even the courtesan began dancing in more revealing clothing. Indian film heroines must meet certain and at times conflicting standards.

For example, the 1988 film Qayamat se Qayamat Tak, literally “doom to doom” ends with both the hero and heroine dead because their parents had not approved of their relationship. The heroine’s relative had left the hero’s aunt pregnant and alone so the two families are forever embittered with each other. This film is one of many variations on the Romeo and Juliet theme and is representative of the roles that the heroine must fill.

While heroines may speak up for themselves, be adventurous and pursue the hero, once her romantic relationship is established she becomes subdued again. Essentially heroines rarely challenged the conventional gender roles. Tawaif in films as main characters likewise tend to reach for the norm of love and a life away from the kotha.

Item songs conversely utilize the world of the tawaif as a vehicle for beloved actresses to show their dancing skills, further the plot, and flip the usual narrative of item songs on their head. Due to the sheer output by Bollywood, I focus primarily on films after 1990.

Courtesans as Distractions and Heroines

Generally when heroines dance for others, it is under compulsion or in connection with some ruse to trick the villain that has place in the narrative. Below are examples of this ruse in films from 1993 to present. Dixit’s Choli Ke Peeche (What’s Underneath my Blouse) was so popular people went to the theaters just to rewatch the song. Here you see her perform seductively as an undercover cop to distract the mustache twirling villain.

Likewise, Sen distracts the villain while the hero, heroine and heroine’s mother attempt to escape in the item song Sun Lo Tum from Kisna set in the 1940s.

In the item song Dil Mera Muft Ka from the film Agent Vinod, Kapoor (also undercover) performs a mujra dance dressed in a more modern take on a gharara, where she distracts the villain and places a bug near him for the hero to listen to the baddie. (There’s also some gay energy in this song.)

Item songs are of course also found in historical films and are examples where the heroine must dance out of compulsion. In Mangal Pandey: The Rising, Mukherji performs as a courtesan in front of the British men before the Indian Mutiny of 1857 in Main Vari Vari. The hero must then save her from one of the British soldiers.

Finally, though certainly not least is Laila Mein Laila from Raees (2017) which features Sunny Leone as a dancer who helps Shahrukh Khan’s Raees in 1990. What the video below doesn’t show is him pulling a dagger from her hair (!) to go after the man who betrayed him.

Prior to British colonialism, tawaif enjoyed their popularity and their talents connected them to men of the highest status. While their representation in Bollywood films are filtered through the male gaze, portraying them as unwilling women forced into their trade who desire to be desired by the hero, these films do not portray their lives realistically.

Elsewhere, those with the heart of gold also do not achieve a happy ending (per the male gaze). Item songs, which allow the tawaif to be the secondary or at times primary heroine, are the exception to the norm and surprisingly allow the tawaif more agency in a span of five minutes compared to feature length films.

Images courtesy of Red Chillies Entertainment, Yash Raj Films, and Mukta Arts.

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!