The Burden of Guilt is a challenging, thought-provoking movie that gets lost in its melodramatics. It would be easy to write the movie off as merely bad instead of flawed, as I almost did, without realizing that the film’s main thrust must be considered through the lens of Voodoo. Voodoo is a religion so often used as colonialist set-dressing that its veracity as a religion seems almost an afterthought.

Written, directed, edited, and shot by Lilton Stewart III, The Burden of Guilt is an obvious labor of love. The earnestness keeps the film from being merely bad and makes it interesting if flawed. Still, despite some of the issues, I found myself wrestling with my own worldview.

As an atheist, I like to think of myself as anti-theist. But what I and most other atheists often overlook is how, despite our rejection of Christianity, so much of our worldview is still steeped in it. This includes our very own personal systems of ethics and justice.

I mention this because Stewart’s The Burden of Guilt uses the lens of Voodoo to look at what ethics mean to us as individuals and as a society. Or at least tries to. The problem becomes that Stewart’s script gets swamped as the subtext becomes text. Yet, there’s an effective theatricality to Stewart’s debut feature that keeps it buoyed.

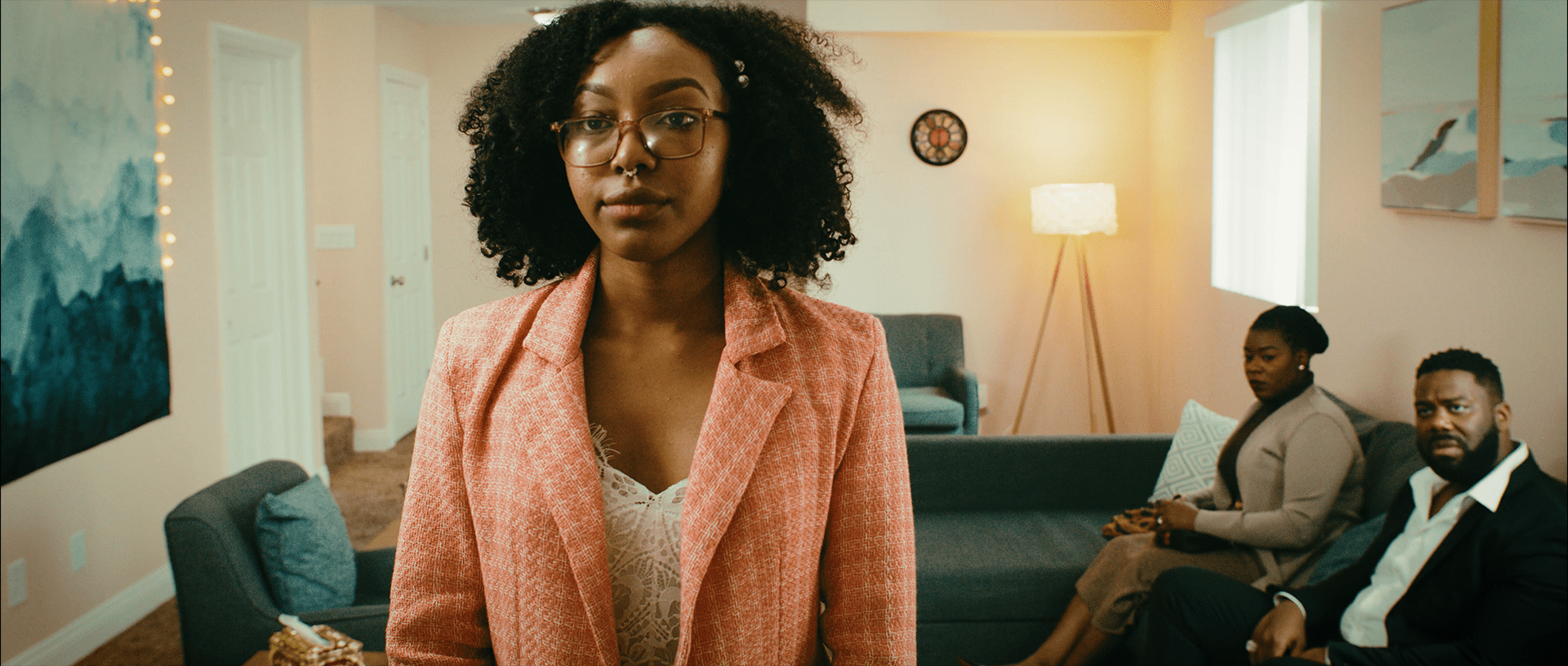

Set in a single room, The Burden of Guilt looks at a married couple, Mallory (Teala Stampley) and Tristan (Torean Thomas), as they seek help from a counselor, the enigmatic Dr. Colburn (Rosa Phil). Stewart uses his camera and editing to create a tactile sense of claustrophobia, making both Mallory Tristan and us feel as if something is off.

However, The Burden of Guilt gets lost in its own dramatics and how it tries to tease out what is happening. In other words, it gets bogged down in trying to play with us, with twists and turns, as opposed to just playing it straight and having the reveals happen for emotional reasons and not for what amounts to an emotional spectacle.

The other issue is how the problems Mallory and Tristan have in The Burden of Guilt are turned up to eleven. Mallory and Tristan aren’t just suffering from trauma and marital woes; they are suffering from the worst trauma and marital woes. For example, the incident that has them seeing the counselor is the death of their son. Only their son wasn’t just murdered; he was kidnapped and molested, and the perpetrators filmed it so that Mllory and Tristan had to watch. Moments like these threaten to derail The Burden of Guilt even as Stewart designs them to draw out his point.

Every secret and sin of the couple that is dragged out feels so outsized and over the top that it blunts the blow of Stewart’s attempt to look at how people often hold onto the burdens of their guilt far after the sins have been committed. Voodoo has no hard set of ethics despite it often being practiced in tandem with Catholicism. It’s less about rules and more about the context of the situation.

Stewart’s camera makes it clear from the start that something is off about Dr. Colburn and her office. It helps Pill, dressed in wedge heels, leather pants, and a black top, feel she’s on her way to the club rather than seeing patients. Pill’s Colburn is a mystery as her performance is neither all that human nor all that otherworldly, possibly because Colburn is meant to be Mawu-Lisa, a goddess that represents duality.

A duality represented by Mallory and Tristan, the Masculine and Feminine. A duality captured by Dr. Colburn, who exudes both traits. The trifecta of the performances is effortless and acutely realized in making Stewart’s point.

Voodoo lacks a being who sits in judgment of mortals. Instead, it has what can be considered a counselor of sorts. Knowing this, The Burden of Guilt begins to take shape, and the flaws become understandable.

As The Burden of Guilt goes on, we learn more and more about Mallory and Tristan and their son’s death. The more we learn, the more heinous the backstory becomes, threatening to overwhelm Stewart’s exploration of his ideas. The wealthy white man who bankrolls much of Tristan’s art, Sir Oliver Wright, isn’t just a corrupt billionaire; he’s part of an evil cabal of billionaires that feels ripped out of a right-wing conspiracy.

Of course, then there’s Jeffrey Epstein, in which case he is merely ripping from the headlines, but therein lies my problem: it all feels so big, while Stewart’s film is so quiet and observant. The point he’s making is valid, but for me personally, it feels like too big a moment to be implied offscreen.

By their confessions, Stampley’s Mallory and Thomas’s Tristan are awful people. The Burden of Guilt opens with Stewart warning us not to throw the first stone, but here is where I struggle the most with my background and the themes Stewart is exploring. To me, there’s not throwing stones, and then there’s the fact that one of them has committed statutory rape. But again, Stewart is trying to make us uncomfortable, his point that in Voodoo belief, there is no heaven and hell, merely a place where all souls go regardless of their crimes. The idea is sound, but the offenses committed offscreen are so grotesque that it proves too big a hurdle.

It doesn’t help that Stampley and Thomas play their characters rooted in a recognizable reality whereas the crimes spoken about feel heavier than the muted recounting they’re giving. Again, however, I recognize that as a white man, my way of telling an event like this would not automatically be the same as that of a person of color. Stampley plays Mallory like a closed flower, blossoming in rage periodically to reveal her true nature. Thomas, by contrast, is more laid back, a venus-fly trap, and seemingly more open until his masculinity is threatened.

Stewart treats Mallory and Tristan not as narcissistic bombs of toxic attitudes with shocking little consideration for those around them. But with great empathy and understanding, as people scarred by a hostile world.

Unspoken during all of this is how the Blackness of Mallory and Tristan only makes the world all the more harsher. The police not taking their son’s disappearance seriously, the wealthy white men showering Tristan with praise, money, and opportunity, and how Mallory’s belief in Voodoo is often met with side-eyed acknowledgment. These moments are where The Burden of Guilt becomes the most interesting.

The little ways in which Stampley and Thomas express their frustration with each other and the little indignities they are forced to suffer, the horror of their son’s death aside. But they are overshadowed by a script that feels like it has ideas that are too big to be explored in only one installment. Too often, Stewart will get stuck in the supernatural aspect of the story, like Mallory becoming hypnotized by the last grain of sand in the hourglass, only to have it amount to nothing.

Stewart’s script suffers from a duality of its own that it never quite resolves, the metaphorical and the literal. As The Burden of Guilt unravels, it reaches a point where it begins to crumble.

Pill’s Dr. Colburn begins to go into detail about how Mallory and Tristan got here and threatens to derail everything Stewart has labored to build. I was taken out of the film as I sat there to what amounted to someone recapping events that happened before the movie and adding nothing except even more trauma.

The monologue is so cumbersome and goes on for so long that not even Stewart’s editing can save it. Stewart cuts the film to keep pace with the reveals, yet at times, shows a flourish and imagination that is absent from the rest of the film. Filming in one room is daunting, and for the most part, Stewart does a fantastic job making use of the space. Though he gets a little repetitive occasionally, it nonetheless adds to the purposeful feeling of being out of time and place.

The Burden of Guilt is a cornucopia of reveals and narrative twists. I haven’t mentioned Amani (Mariah Salae), Dr. Colburn’s assistant. However, we soon realize that Amani is more than that, which leads back to Stewart’s tendency to make everything a reveal. The way the script is constructed makes the sins and offenses feel somewhat rushed without enough time to explore them properly.

But then we get to the very last scene with a fly. I won’t say anything more than that. But man, I unironically love that fly. The audaciousness and ludicrousness that exploded in that final moment made me pine for a movie even more imbued with that sense of imaginative verve.

Images courtesy of November 11th Pictures

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you want to talk about with fellow Fundamentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!