- Caleb Meyer (pt. 1): Gillian Welch Confronts trauma and Misogyny In Her Music

- Caleb Meyer (pt. 2): Non-Survivor privilege Influences How Critics Review Music

- Caleb Meyer (pt. 3): This Sequel To A Feminist Murder Ballad Embodies Male Entitlement

Content warning: discussion of sexual assault

Introduction:

If you’ve been on the Internet long enough, you’ve probably seen memes about the subgenre of country music songs that tell stories about women who kill their sh*tty husbands. That subgenre, though affiliated with country, actually extends to all types of music. This narrative trope, the feminist revenge against abusive men, is very old, very kickass, and very defiant of dominant musical tropes that has shaped American songwriting for over a hundred years. It’s women’s collective response to the misogyny that has permeated songs known as ‘murder ballads’. Though it’s mainly associated with folk and country, the ‘murder ballad’ embraces a variety of sounds. Even the Broadway classic ‘Cell Block Tango’ falls under the murder ballad umbrella.

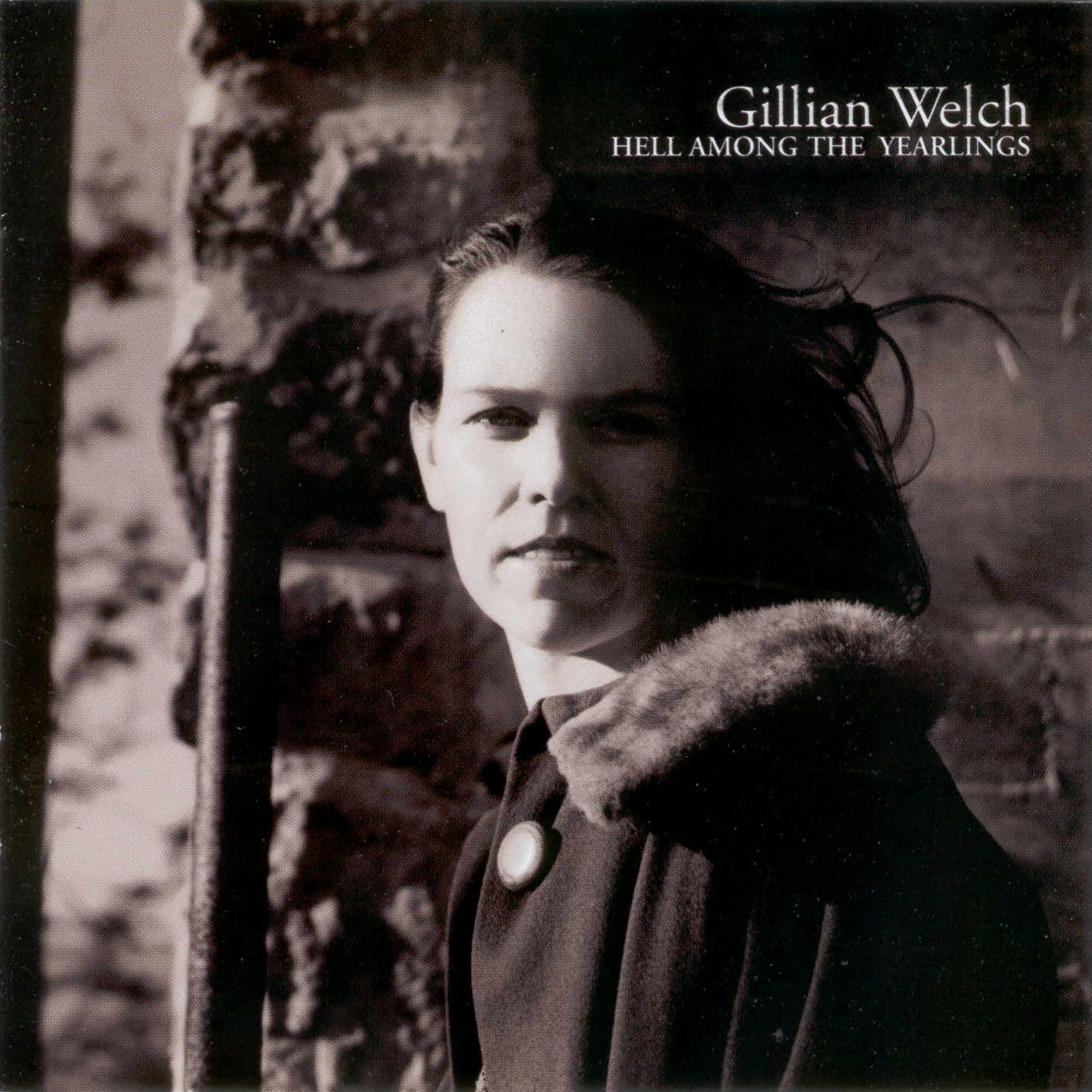

In 1998, Gillian Welch released her second album, Hell Among the Yearlings, and its first track, ‘Caleb Meyer’, reverberated through the folk and country scene. The song still remains a ‘fan favorite’, as noted by The Tennessean, and a staple number for Welch’s shows, more than twenty years later. ‘Caleb Meyer’ details the story of an Appalachian woman named Nellie Kane when the titular character attempts to rape her, forcing her to kill him. It’s a harrowing tale, as old as the lonely mountains that Welch often features in her work, and in many respects, it’s a story that’s too often been silenced. ‘Caleb Meyer’ remains unique as a feminist murder ballad because of how it handles the protagonist’s trauma in a way that simultaneously reassures and disturbs listeners. It is validation and condemnation all at once.

Murder Ballads & Their History of Misogyny:

Because of its criminal and murderous subject matter, ‘Caleb Meyer’ belongs to the centuries-old tradition of the murder ballad. Murder ballads are musical compositions whose lyrics are narrative-driven, relaying stories about crime, particularly murder. The American murder ballad has its roots in folklore and British songwriting, a product of cultural transmission and humanity’s fascination with violence. The ballad as we hear it, specifically the narrative-verse structure seen in folk music, comes from Great Britain. Balladeers often took inspiration from real-life murders, and ballads were then often passed orally, the verses sometimes changing, along with details and names, embedding into culture like a legend. While associated with a dark subject, murder ballads can be downright upbeat.

Caitlin Kirchner notes that in the nineteenth century, the American murder ballads we know today began to take shape, and that misogyny began to seep into the genre’s DNA. She writes, “Most commonly, murder ballads in the United States recount the story of a man dominating and killing a woman. Songs typically depict a passive female victim who does not resist her killer. Ballads usually reveal no specific motive for the killing, nor punishment for the murderer,” (p. 7). In fact, these songs are referred to as ‘murdered girl ballads’ because so many songs throughout the past hundred and fifty years have relayed the same sort of story. Sometimes sexualized, sometimes blamed, all passive victims. And it’s generally agreed upon that the murdered girl ballad developed partially in response to women’s growing independence in the nineteenth century, the deadly songs a warning to young women who embraced their sexuality outside of marriage.

Women have always sung murder ballads. But the past few decades, as women have gained more power and freedom and the ability to tell stories about the female condition, murder ballads have more often made female characters active rather than passive, whether for self-preservation or for revenge. Domestic violence and infidelity often motivate these fictional women to take control of their lives, and whether seen for their heroism or their villainy, these women express agency. That’s why I like to think of this subgenre as ‘feminist murder (power) ballads’. Some female artists specifically wrote their murder ballads as a response to the misogynistic tropes. For example, Valerie June and Kesha wrote about women feeling murderous because of infidelity for their songs ‘Shotgun’ and ‘Hunt You Down’. (‘Hunt You Down’ isn’t a pure murder ballad because the narrator only threatens to murder her partner if he cheats, but it falls within the purview of the genre.)

And of course, patriarchy being patriarchy, women cannot tell stories about female revenge and violence without controversy and criticism. Up until recently, female musicians risked backlash for recording songs about women getting back at men in morally dubious ways. For example, Martina McBride and The Chicks each released a song about a woman killing her abusive husband, and some radio stations subsequently refused to play the songs, in 1994 and 2000 respectively. Radio programmers, to reiterate, did not want to play these sorts of songs because they didn’t want to acknowledge the prevalence of domestic violence and couldn’t stomach the thought of a woman being violent, even if in self-defense. By censoring these songs from airwaves, media platformers helped to censor the subjects behind the songs, reinforcing the subversive elements of women writing and singing feminist murder (power) ballads.

Gillian Welch released ‘Caleb Meyer’ in the late ’90s during the midst of all this.

‘Caleb Meyer’ As a Song:

‘Caleb Meyer’ absolutely falls into the murder ballad tradition, though it’s less mainstream and more traditionally folksy than its country sister songs. In my opinion, the song’s staying power and distinctiveness within this subgenre comes from how its tone and portrayal of the murder differ from other feminist murder ballads.

Certain feminist murder (power) ballads like ‘Church Bells’ (Carrie Underwoman) and ‘Independence Day’ (Martina McBride) describe the woman’s vulnerability from abuse, thus making her choice to step up all the more powerful. ‘Goodbye Earl’ (The Chicks) is a maniacally gleeful joyride bolstered by a music video that has elements of a black comedy, and ‘Gunpowder & Lead’(Miranda Lambert) might as well be spitting bullets, the narrator confident in her aim and in herself, unafraid of her abuser even though he’s just been released from jail. None of these murder ballads address how killing her abuser affects the woman emotionally. (‘Goodbye Earl’ implies exuberance and relief, but life is typically way more complex than that.)

Similarly, songs about surviving domestic violence usually do not wade into the emotional fallout. Songs like Jennifer Nettles’s ‘His Hands’ and Kellie Pickler’s ‘Wild Ponies’ narrate the woman’s seduction into the relationship, the escalation into abuse, and her eventual escape, symbolized by packed bags or driving away. These songs, due to their narrative structure having the climax be the escape, do not address the subsequent trauma. Because there’s experiencing trauma and then there’s the quiet nights after, having to process man-made horrors alone.

Gillian Welch not only portrayed the horror of male violence, she also focused on the aftermath, and her unflinching look into the trauma of sexual assault likely validated many survivors.

She co-wrote the song with her musical partner David Rawlings in October 1997, and it was the first song she wrote for the record (Du Lac, p. 166). Welch made a bold choice placing ‘Caleb Meyer’ at the beginning of her second album. The late ’90s were not the best decade for women in terms of sexual violence, even after the gains made thanks to the women’s movement over the preceding twenty years. At the time, 1998, the term ‘acquaintance rape’ was about twenty years old and only five years earlier, John Wayne Bobbitt had been acquitted of raping his wife, Lorena Gallo. The trial made headlines at the time, as Gallo had cut off her husband’s penis, alleging that after repeated sexual abuse she took a knife and matters into her own hand. (Marital rape had only been criminalized in all fifty states in 1993, as well. Go patriarchy!)

For a story like Nellie Kane’s, which dealt with sexual assault by an acquaintance, Welch’s sympathy for her protagonist resonated deeply with listeners. This is evident by its many covers, particularly by women, and by its appearance in numerous blog posts and academic literature. The quartet The Hollering Pines even took their namesake from lyrics in the opening verse.

Welch sings ‘Caleb Meyer’ in the first-person and from Nellie Kane’s perspective, even though she isn’t the title character. Several murder girl ballads, such as ‘Omie Wise’, which happens to be one of the first of its kind, are titled after the murder victims. Welch subverts murder ballads from the song’s very title, implicitly adding another layer of focus, and thus blame, on Caleb Meyer.

The song opens with Nellie Kane describing her neighbor’s isolation in rural Appalachia, specifically “in them hollerin’ pines”. Nellie Kane adds, “[H]e made a little whiskey for himself/Said it helped to pass the time.” The imagery recalls old-timey cabins and moonshine stills from Prohibition, the mountainside as windswept and as lonely as any Gothic moor. Tyler Dean outlines the Gothic genre and its prevalence of female protagonists and writers. In a sense, Welch’s ‘Caleb Meyer’ is the melodic, Americana version of the “peculiar mixture of loneliness and sexual menace that defines so much of the Gothic of the late 18th and early 19th centuries”.

‘Holler’ is also the Appalachian pronunciation of ‘hollow’, a term for a valley. And by phrasing the pine trees as ‘hollerin’’, Welch evokes the idea of the trees screaming, a ghostly wail. The sensory detail about the “hollerin’ pines” implies, in my opinion, the prevalence of sound in Nellie Kane’s trauma and how Caleb’s voice haunts her after his death. Welch seeds this most concretely in the following verse:

Long one evening in back of my house

Caleb come around

And he called my name ’til I came out

With no one else around

The image of Caleb calling for Nellie Kane then flows right into the chorus:

Caleb Meyer, your ghost is gonna

Wear them rattlin’ chains

But when I go to sleep at night

Don’t you call my name

The reference to his ‘ghost’ makes clear that the chorus takes place sometime later and reveals to listeners that at some point, Caleb Meyer is going to die. And I like Mark A. Plunkett’s comparison of Caleb Meyer’s chains to Jacob Marley’s from A Christmas Carol. Nellie Kane believes that in whatever afterlife there is that her attempted rapist won’t know peace, forced to carry the weight of his crimes for eternity. Welch’s word choice highlights sound once again, the chains described not by their heaviness but their ‘rattlin’’ and by Nellie Kane referencing Caleb Meyer’s voice. Her reference to sleeping at night implies that her trauma affects her ability to sleep and brings her nightmares. She fixates on him calling her name because when she stepped outside her house, she unknowingly crossed a threshold marked by a ‘before’ and an ‘after’. The other murder ballads that I mentioned earlier do not reference triggers. ‘Caleb Meyer’ is one of the most psychologically driven murder ballads in terms of focusing on the woman’s reaction to trauma.

In the second verse, we learn Nellie Kane’s name when Caleb Meyer asks her about her husband. He then asks, “Did he go on down the mountainside/And leave you all alone?” Nellie Kane affirms that yes, she is alone, as her husband went on a business trip to the city of Bowling Green. She subsequently recounts that “Then Caleb threw that bottle down/And grabbed me by my hair.” This sequence of events, and Welch having Nellie say ‘Then’ before Caleb Meyer throws his bottle down stresses that he bided his time before attacking her.

The character’s propensity for whiskey and the speed of his attack could lead one to think that Caleb Meyer attacked Nellie Kane because he ‘lost control’ thanks to alcohol fueling male desire. While alcohol is never an excuse for sexual assault, Caleb Meyer’s line of questioning helps to undermine the myth of out-of-control rapist, as he waits until he knows for a fact that Nellie’s husband won’t be home for a while. That she is, in his mind, totally helpless and defenseless.

After another chorus reprise, Gillian Welch sings a three-part bridge that depicts Caleb Meyer’s attempted rape of Nellie Kane and her killing him in self-defense. Nellie Kane continues to narrate this portion, Welch’s vocals still fast and breathless. Caleb Meyer throws Nellie Kane to the ground, and because of the pine trees, she describes it as a ‘needle bed’. Welch’s word choice of ‘needle bed’ for this scene stresses the violative nature of sexual assault and connects back to the details from the second verse. The image of a ‘needle bed’ contrasts to the implied ‘marriage bed’ between Nellie Kane and her husband, reinforcing that Caleb Meyer waited until Mr. Kane was gone so he could take Mr. Kane’s ‘place’.

Our heroine begins to pray, crying out to God for him to send angels. Nellie Kane then recounts that she discovered the broken neck from Caleb Meyer’s bottle, and she uses it as a weapon to save herself, the implication being that no salvation came from Heaven but from within. It’s that Gothic loneliness again, except transplanted to Appalachian mountains rather than an English moor, and one that leaves the listeners and Nellie Kane to question the idea of God. The debate around divine intervention in this song, whether Nellie Kane’s prayers were answered or whether she just got lucky with that bottle, make the scene all the more tragic. Fittingly, the final stanza is cinematic and action-based, a flashback stripped of emotion:

I drew that glass across his neck

As fine as any blade

Then I felt his blood pour fast and hot

’Round me where I lay

Gillian Welch’s songwriting makes listeners fill in the emotional blanks and empathize with Nellie Kane. The bridge ends with the image of a dead Caleb Meyer splayed across a stupefied Nellie Kane, covered in his blood, and the sensory detail about the blood adds another layer to the horror, giving listeners a physical feeling to latch onto. Welch does not provide catharsis with a bridge or final chorus that unleashes a torrent of emotions, her vocals still restrained and Nellie Kane still not saying exactly what she feels. We’re just left, like Nellie Kane, thinking about Caleb Meyer and how him calling her name still echoes through the hollering pines of her mind.

‘Caleb Meyer’ is a murder ballad because it tells the story about a woman killing a man, but that’s not what ‘Caleb Meyer’ is about, not really. Music site Sing Out! put it best, back in 2014, describing ‘Caleb Meyer’ as a “survivor’s ballad”. Gillian Welch’s song represents the opposite of non-survivor privilege in that it prioritizes the character who has to survive the trauma and centers her feelings within the story, no matter how difficult they are.

Conclusion(ish):

Gillian Welch succeeds in telling a story that captures the spirit of anxiety and apprehension women struggle with when alone due to rape culture and the terrible possibilities of that isolation, while remaining true to the sound and style of traditional murder ballads. I never found any reference to backlash against this song, interestingly, making it unique to other feminist murder (power) ballads of the time. But I did discover some… interesting responses from the male half of the music world.

As evident by the title, this article is only the first part of a series on ‘Caleb Meyer’. Today I’ve explored why this song resonates so much, more than twenty years since its release. Creators’ responsibilities when it comes to depicting interpersonal trauma matters a lot to me, clearly, by the general themes of my writings here. It’s related to that good old ‘non-survivor privilege’ in the media once again.

But non-survivor privilege also reflects in how people respond to art about someone’s marginalization, and in terms of rape culture, stories about women surviving male violence, we cannot ignore gender politics. So, parts two and three I will discuss how men have reacted to Gillian Welch’s music, with the not-so-subtle misogyny, and how certain men have interpreted these verses, which reflect subtle non-survivor privilege.

Time to activate my feminist killjoy rants! And if you want to hear more about womenand revenge stories, check out the newest Ladies First episode tomorrow! Kori and I are going to go off about the double standards in revenge stories.

Images courtesy of Gillian Welch

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!