Content warning: article contains discussion of abuse, including child abuse and sexual assault; Spoiler warning for Captain Marvel (2019)

Introduction:

When the first Captain Marvel trailer dropped a year ago, those frustratingly familiar dudebros crawled out from the digital woodwork. They declared that the character should “smile more”, and one of them went so far as to photoshop open-toothed smiles onto Carol. Brie Larson, in perfectly petty fashion, posted a series of Instagram Stories with smiles photoshopped onto other Marvel characters like Captain America.

The film’s potential provided some needed relief and some hope for women everywhere. At the same time a year ago, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford had just gone public with her allegations against Brett Kavanaugh. The whole experience further divided the country. For women, it encapsulated the struggles we face in a world that objectifies us while also demanding us to perform emotional labor with saintly patience. What I remember most clearly though about that injustice was the Trump rally soon after. The President mocking a sexual assault survivor to roarious laughter from his followers. Him bellowing, “I don’t know,” to discredit Blasey Ford’s testimony. It embodied the connection between the political and personal.

The traumas faced by an individual and by a people work together — they worsen and reinforce each other.

How fitting is it then that a movie, which previewed at the time, focused on a woman who struggled with her memory because of trauma? The movie even goes further and addresses the identity crisis caused by complex trauma, one of the least discussed yet most prevalent subjects in psychology today. It frames her arc alongside the xenophobia and imperialism that cost the Skrull race their planet. Her years-long pain makes sense when understood as a personal diaspora and otherization akin to the Skrulls.

For my first ever article, I referenced Judith Herman’s 1992 book, Trauma and Recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror (specifically the 2015 reprint). I used her stages of recovery to frame El Hopper’s character arc. For this article, I will also use the stages of recovery to interpret Carol’s arc, though will do so more explicitly than in my past work. Herman argues that certain traumas can only be resolved through political awakening and activism, and the film pulls that together more so than Stranger Things due to the nature of its character and story. Captain Marvel succeeds at depicting complex trauma because it interweaves Carol’s traumas into the story’s political conflicts, reflecting the relationship between interpersonal and systemic violence. It acknowledges the perpetrators and the forces that empowered them.

A Patient Diagnosis:

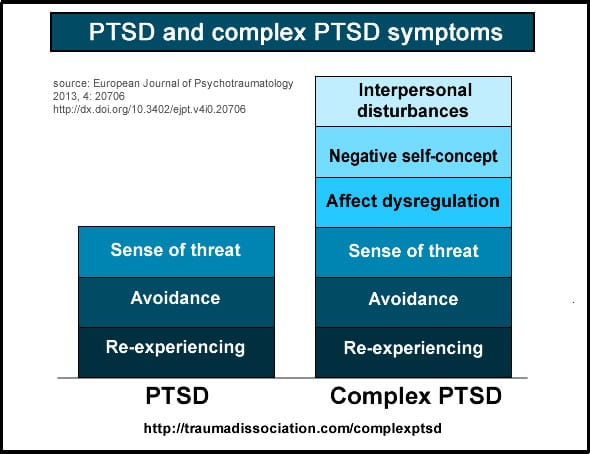

Though considered by psychologists before her, Herman codified complex trauma as a diagnosis, centering it as an extension of the better-known P.T.S.D. She worked with and treated targets of abuse for decades, realizing that, “Traumatic events are extraordinary, not because they occur rarely, but rather because they overwhelm the ordinary human adaptations to life,” (p. 33). And so complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) entered academic literature in 1992. She placed it as a long-needed diagnosis in a field rife with victim blaming.

You will not find C-PTSD in any official American capacity. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the typical criteria for American mental healthcare providers, has yet to add C-PTSD. The World Health Organization (WHO) though officially added C-PTSD to its diagnostic manual last year:

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder […] is a disorder that may develop following exposure to an event or series of events of an extremely threatening or horrific nature, most commonly prolonged or repetitive events from which escape is difficult or impossible (e.g., torture, slavery, genocide campaigns, prolonged domestic violence, repeated childhood sexual or physical abuse).

In many ways, the ‘C’ can stand for captivity. Unfortunately though, Herman and WHO never mentioned that psychological abuse can cause C-PTSD. (For reference, whenever I refer to “psychological abuse”, I use it as an umbrella-term for emotional, mental, and verbal abuse as it, in my opinion, best encapsulates the connections between different techniques of terrorization and grooming.)

With Herman’s work in mind, I did some quick Googling on Captain Marvel and trauma to see what critics might said. I quickly found two blog posts on women with C-PTSD who connected to the film, one of whom even brought up Trauma and Recovery. Their writings confirmed my theory that Carol’s story would resonate for people with this diagnosis. To be clear though, I am not suggesting C-PTSD as a diagnosis for Carol. I only use it as a lens for analysis to better understand character dynamics and themes. Due to her situation and the short timespan of the film, she technically does not go through the stages. And it’s still useful to use the stages as a way to conceptualize her arc. Her time as Vers hints towards a disruption in her socialization and sense of self, stemming from her abduction and grooming.

With Herman’s work in mind, I did some quick Googling on Captain Marvel and trauma to see what critics might said. I quickly found two blog posts on women with C-PTSD who connected to the film, one of whom even brought up Trauma and Recovery. Their writings confirmed my theory that Carol’s story would resonate for people with this diagnosis. To be clear though, I am not suggesting C-PTSD as a diagnosis for Carol. I only use it as a lens for analysis to better understand character dynamics and themes. Due to her situation and the short timespan of the film, she technically does not go through the stages. And it’s still useful to use the stages as a way to conceptualize her arc. Her time as Vers hints towards a disruption in her socialization and sense of self, stemming from her abduction and grooming.

Stage 1: Identity and (Safeish) Distance

Stage one focuses on establishing safety. When we meet Carol Danvers, she is living on Hala, the central homeworld of the Kree Empire. She suffers from amnesia and goes by the name of ‘Vers’, training as a superpowered soldier under Yon-Rogg. The film explores the relationship between identity and memory as Carol discovers her earthly origins, reconstructing her time as an Airforce pilot. Eventually, she learns that Yon-Rogg was the alien who murdered her mentor and abducted her, training her to become an emotionless weapon.

Because of her amnesia, Carol’s abuse shares more similarities with people in abusive interpersonal relationships than with political prisoners. Her conscious mind is not aware of what actually happened to her, making it easier for the Kree to manipulate her as they can pass themselves off as her savior. Her earliest memory symbolizes the Kree’s colonialization of her mind: She remembers waking up to a blood transfusion, Yon-Rogg’s blood injected into her veins. It reinforces her hybridized genetics, the blue alien blood overtaking her red, human blood. The slowness of a transfusion fits as a metaphor for the slowness of abuse and its warping of identity, the sense of ownership that a perpetrator has for their target.

When the film starts, we see Carol in a nightmare, reliving a version of her abduction: she watches as a Skrull prepares to kill her and her original mentor, Dr. Wendy Lawson. It differs from the original memory as she remembers it later, reflecting the story that she was told by the Kree. The camera stays close on her as she wakes up, obscuring any details of her personal quarters. When she walks over to the window, she is surrounded by reflections of the cityscape, subsumed in Kree identity and culture. She already belongs to the Collective in a way; we only know Vers as a warrior, severed from her inner world.

Most of the manipulation lies in her relationship with Yon-Rogg. He sees her as a protegée, toeing the line between parental figure and friend. As a character, he embodies patriarchal authority figures that women must deal with throughout their lives. During their sparring match, he admonishes her for her emotions, repeating the Kree ideal of stoicism. His disparaging of her (human) emotions recalls statements like, “You’re too sensitive,” which come up often in gaslighting. It foreshadows the more explicit gaslighting that he uses when she begins to question her origins. Her residual anger and humor endanger his grooming attempts — they fuel her independence and her boundaries. He tells to let go of her past and refuses to be vulnerable, hiding his true self:

In situations of captivity, the perpetrator becomes the most powerful person in the life of the victim[.] Little is known about the mind of the perpetrator. Since he is contemptuous of those who seek to understand him, he does not volunteer to be studied. […] His most consistent feature […] is his apparent normality. (p. 75)

He stifles vulnerability with Carol, and by doing so, he discourages her to self-reflect. This itself is a form of gaslighting as he caused her amnesia and knows why she suffers. In a deleted scene, Yon-Rogg meets with the Supreme Intelligence, revealing the person he most admires: himself. It is the ultimate collaboration between personal and political forces.

Indeed, the Supreme Intelligence’s method of communication parallels Yon-Rogg’s transfusion. The Kree allow the A.I. to ‘plug’ into their body and mind, visualized as fluid-like vines, and the imagery recalls a creeping infection as a perpetrator infiltrates the target’s consciousness. They hijack the target’s thoughts, and eventually their negative voice in the target’s head transfigures into the target’s own. The Supreme Intelligence takes the form of whoever the person most admires, another layer of emotional manipulation and pressure. It also subtly threatens to take away her powers if she doesn’t submit: “What’s given can be taken away.” It makes her safety and agency conditional on her ability to conform and obey. Kree propaganda, such as the citywide announcement about Skrull attacks, reinforces the Skrulls as terrorists, reminding Carol of her trauma. She lives in a state of low-level, constant fear that what happened to her will happen to others.

Though well-executed, the film could have used a scene or two to develop Hala and to develop Vers. We never see the Vers identity outside a military context, so she can’t be contrasted to Carol’s life on Earth. There is a deleted scene of Yon-Rogg and Carol speaking to schoolchildren about danger, but it lacks the power that comes from quiet cultural cues of propaganda. This is where safety comes in. As Carol gains physical and mental distance from Yon-Rogg and the Kree empire, her personality opens up. She can more fully express her emotions, and her bond with Fury offers the first known relationship in years not based in her abduction.

As a result of this, Yon-Rogg escalates his gaslighting in an attempt to reestablish control over Carol. When she and Fury discover the file on Lawson, pictures of the crash site trigger her viscerally. Larson brought her experiences from Room, a film about a woman and her son surviving captivity, and infused them into her acting for Carol, especially in this scene. The subtle acting techniques, which become more obvious in rewatches, include the million-yard, dissociative gaze and mild changes in breathing. When she sees pictures of the crash site, Carol begins to fold in on herself, her mind simultaneously racing away and short-circuiting. Her reduced verbalization and breathing are symptomatic of the brain when triggered, adrenaline flooding her system as buried memories break through her subconscious. She calls Yon-Rogg in an attempt to make sense of the pictures:

Carol: I found evidence that I… had a life here. […] Mar-Vell is who I see when I visit the Supreme Intelligence. I knew her. And I knew her as Lawson.

Yon-Rogg: This sounds like Skrull simulation, Vers.

Carol: No, it’s not because I remember. I was here…

Yon-Rogg: Stop. Remember your training. Know your enemy. It could be you. Do not let your emotions override your judgment.

Notably he does not ask about what kind of evidence she discovered or what she remembers. He instructs her to disavow herself and to only trust him and the Kree, the ‘authorities’ in her life. His implication that the Skrulls hijacked her mind, hence her reaction, is a red herring. Often emotions inform a person’s judgement. Like physiological responses, emotions help to shape one’s understanding of the world, inspiring self-reflection and insight. He infantilizes and gaslights her here, attempting to reassert his power over her by deriding her agency and sense of self. He knows that her subconscious mind holds the truth, and should that be unlocked, she could access her full power physically and psychologically.

Later, Carol and Fury discuss their status as outsiders in their respective units. Fury remarks that his coworker “went with his gut against orders” and connects it to humanity’s innate nature. Carol, laughing it off, says that following her instincts tends to get her into trouble. Counselor Kris Godinez has discussed in her videos that research now points to the gut being like a second brain. By attempting to quell even her instincts and emotions, Yon-Rogg tries to infiltrate the innermost levels of her humanity and independence, yet Carol is a resilient survivor. This resilience forms the backbone of her strong will as she charges forward toward the truth.

Stage Two: The Self-De(con)struction that is Memory

Arguably, the longest stage in the process is the second stage. That period in a target’s life centers on grieving, awash in memories. It creates a philosophical, existential crisis for the target: “She stands mute before the emptiness of evil, feeling the insufficiency of any known system of explanation,” (p. 178). The return of Carol’s memories about her powers and subsequent abduction trigger this crisis. She realizes that everything she knew about herself was rooted in lies and in blood. This is a hallmark of C-PTSD rooted in interpersonal abuse and exploitation, because targets like political prisoners know who their enemy is initially, even if they end up submitting later. In an abusive intimate relationship, such as a partner or parent, the target had to be groomed to accept maltreatment over time.

Abuse in general, but especially gaslighting, warps the memory-making process. Targets struggle with gaps and black holes, so it’s recommended that targets write down incidents of abuse to counteract the gaslighting. These written records function as externalized memories and consciousness, and in Captain Marvel, the file on Lawson and the black box from the plane crash serve a similar purpose for the narrative. Not only are they triggers, speeding up the mental processes that the abused mind goes through, they are indisputable proof for Carol.

Abuse in general, but especially gaslighting, warps the memory-making process. Targets struggle with gaps and black holes, so it’s recommended that targets write down incidents of abuse to counteract the gaslighting. These written records function as externalized memories and consciousness, and in Captain Marvel, the file on Lawson and the black box from the plane crash serve a similar purpose for the narrative. Not only are they triggers, speeding up the mental processes that the abused mind goes through, they are indisputable proof for Carol.

Earlier in the film, Fury had summarized the Kree as “a race of noble warriors,” but Carol immediately and proudly corrected him, declaring that she comes from a race of “heroes.” She repeated her assertion: “noble warrior heroes.” By stressing “heroes” in the dialogue, the writers build up the inevitable trauma that comes from her disillusionment. The file on Lawson thus opens the door in her mind, while the black box turns on the light.

The betrayal shatters her trauma bond with Yon-Rogg and her understanding of the world, as she begins to realize her part in genocide. Her empathy and innate goodness amplify this dehumanization, her having been tricked and reduced to a weapon: “It is at this point, when the victim under duress participates in the sacrifice of others, that she is truly “broken,” (p. 83). To demonstrate this, Herman cites Elie Wiesel, a Holocaust survivor, and describes how his bond with his father had been temporarily compromised by the guards’ abuse. At one point, Wiesel failed to protect his father and felt a rush of anger toward him, not the guards. Herman then explains that, “The sense of shame and defeat comes not merely from his failure to intercede but also from the realization that his captors have usurped his inner life,” (p. 84).

After listening to the black box, Carol struggles with Talos’s assertions that the Skrull aren’t terrorists, trapped in the cement that is cognitive dissonance. He appeals to her psychological diaspora to break through to her, explaining that, “We just want a home. You and I lost everything at the hands of the Kree. Can’t you see it now? You’re not one of them.” By positioning her with him and against the Kree as a binary ‘us versus them’, he reverses the rhetoric used by dominant groups to other marginalized peoples and communities.

Carol pushes back in this scene, dividing herself from their shared experiences, as she angrily states, “You don’t know me. You have no idea who I am. I don’t even know who I am!” In terms of C-PTSD, the perpetrator invaded every element of the target’s sense of self. Singular trauma draws a sharp line between a before and after, but long-term trauma is the erosion of boundaries, everything blurred and distorted to the point that targets often give up on their humanity. For Carol, this takes on a literal meaning as the explosion changed her DNA, and Yon-Rogg infiltrated her body through the blood transfusion.

The scene takes place outside at sunset, representative of the ensuing darkness of recovery and the end of her life as Vers. It bookends the beginning of the film when she wakes at early dawn from the nightmare. As she explored the mystery of Lawson with Fury, she did so during daylight, and when she goes up into space, meeting Skrull survivors, she faces her demons in a very physical way. The Skrull were demonized, and their alien features and shapeshifting abilities work well as a metaphor for the different Others we have hurt in positions of ignorance, power, and privilege. Indeed, they share a resemblance with mythic goblins and incubi. To use shapeshifters as a metaphor for marginalized people is brilliant, reflecting how both sides of oppression can be masked. The Kree use the Skrulls’ fluid nature to camouflage the cracks in the system, and symbolically, their powers make them convenient scapegoats.

That being said, the film could have benefitted from a drawn-out breakdown scene, so Carol and the audience could have had more time to process her awakening to Kree imperialism. Instead of immediately being comforted by Maria, Carol could have stormed off further into nature, perhaps finding herself in the swamp shack. The other characters could have then found her there, leading to the same exchange. The setting, a liminal space, would have also had more symbolic resonance.

The second stage culminates in Carol’s second confrontation with the Supreme Intelligence. Without any structures or support, she faces up against its manipulations and reaffirms her identity. The song that plays at the beginning of this scene, Nirvana’s ‘Come As You Are’, reflects the tension related to identity, autonomy, and conformity. Viewers can hear the opening lyrics, “Come as you are, as you were/As I want you to be,” most clearly, alluding to the Supreme Intelligence’s goals. Lyrics referencing memory, trust, and weaponry litter the song. In an interview, Kirk Cobain even explained that, “[The song is] people, and what they’re expected to act like.” Accordingly, the Supreme Intelligence proceeds to infantilize her, accusing her of being unable to control her powers. The Supreme Intelligence’s derision is inherently gaslighting as it and Yon-Rogg had restrained Carol and her powers, tightly monitoring her.

The scene also reinforces the contrast between the ‘death’ of Vers and the resurrection of Carol. The Supreme Intelligence compares the Vers identity to a rebirth, referencing the remaining scrap from Carol’s dog tags. In political and social captivity, perpetrators will sometimes change the target’s name as a way to disconnect them from their identity. Herman cites cases like Patty Hearst and Linda Boreman, who were both systematically beaten and sexually assaulted into compliance and renamed (p. 93). Terrorists had abducted Hearst and reprogrammed her as the criminal ‘Tania’, while Boreman had been seduced into an abusive marriage and coerced into pornography, becoming the infamous Linda Lovelace. When Carol says, teary-eyed but her eyes steely-gazed, “My name is… Carol,” she is reasserting control. In terms of trauma recovery, she is also addressing the negative self-concept and interpersonal disturbances seen in C-PTSD. Those symptoms arose from the Kree objectifying her, the numerous betrayals, and the loss of her identity. Though she may never be again the Captain Carol Danvers of Earth, she will always, intrinsically, be the woman who risks her life to help others, who loves flying, and who is too much of a wisecracker for her own good.

Stage Three: Political Monument

Having passed through many nights of grieving, the target comes to reintegrate into the community as a survivor. The trauma, whether it be a one-time assault or years-long struggle, has fallen into the survivor’s story. But it is no longer the only story. Carol experiences this release when she confronts Yon-Rogg after finally having learned the truth. Knowing that he could not stand against her fully empowered, he calls on their earlier matches and his expectation that she abstain from using her powers, squelching her anger. As perpetrators are wont to do, he tries to manipulate her till the very end of their relationship. He even attempts to gaslight her one final time, referring to when he “found [her] that day by the lake,” erasing his hand in her abduction and Lawson’s murder. Without a word, she blasts him the ground and asserts that, “I have nothing to prove to you.” It is the first step towards the indifference that marks long-term trauma recovery: the freedom of unburdening the anger, converting it to righteous indignation. No longer need his validation, she also no longer needs to prove the trauma to herself, ridding herself of abusive influences.

Their last scene together also takes place in a desert. It contrasts against the swamp and woods of Louisiana — the dark, messy second stage. With stage three, comes clarity and a withering, unflinching gaze. In Western literature, deserts have often been the setting for major character transformations and epiphanies, due to Biblical influence. Our protagonist, having navigated the psychological space between Captain Carol Danvers and Vers of Starforce, has come out the other side as Carol, taking up the mantle of Captain Marvel in honor of her mentor. It represents a balance in her earthly heritage and Kree rebirth.

In addition, stage three also comes with the target usually taking up community work and activism. The slogan ‘the personal is political’ originates in second-wave feminism, discussing how feminist theory can transition into feminist praxis and the ripple effect of institutions on the everyday. When summarizing the film, Lara Witt wrote:

Loud girls become loud women if they aren’t controlled early on. Loud women are dangerous, we are disruptive, we refuse to absorb pain in silence—a silence which only upholds oppressive structures and its beneficiaries. […] “Captain Marvel” managed to weave what we intimately know about the oppression that exists in our world and showed us that what our oppressors fear the most is us using our rage and our empathy to avenge those who are being harmed.

In Captain Marvel, the personal is the political and the political is personal for her. She hurt others while under the influence of Kree propaganda, simultaneously a pawn and a target in an unjust war.

Indeed, her abduction would be recognized as trauma by society, though her years of being gaslit might not. In war, communities recognize soldiers’ traumas and violations, constructing physical monuments that represent public solidarity (p. 71). Interpersonal trauma, which most often affects women and children, typically will not be acknowledged in the justice system. Barred from legal restitution and acknowledgement, targets have the best chance at successful recoveries by incorporating their pain into “social action”, bringing the private into the public. As Herman summarizes it, “[I]n demanding social change, survivors create their own living monument,” (p. 73). The film concludes with doing just this, her own body a monument to her experiences and her survival.

The film concludes with Carol deciding to help the Skrulls find a new home. She flies off into space wearing her Americanized Starforce uniform as well as her old leather jacket. In captivity and in trauma recovery, targets use “transitional objects” to connect with their past selves and to bridge the fractured self with the future (p. 81). Her body combines American and Kree imagery, reinforcing that though Carol Danvers and Vers are no more, they still live inside of her. She is Carol, and she knows that will help people, no matter what they call her. And that is enough.

Coming Back Down:

Over this past weekend, The New York Times reported on another allegation against Judge Brett Kavanaugh. Its Twitter account disturbingly posted the link with a caption about one of the allegations, connecting sexual assault to humor. Though the account later deleted it for being “poorly phrased”, its mere existence is a sobering statement. It stands as proof to the deep roots of rape culture, paralleling the infiltration and entanglement of the Supreme Intelligence and Kree xenophobia.

At the same time a year ago, I was working nights at my university’s violence intervention and prevention center. (It had originally been a woman’s center but was redesigned for inclusivity). On the day of the hearing later that September, my boss informed me that the center would be providing support all day. Survivors were being triggered, particularly women, and we were going to stand in solidarity. I registered what she said, had registered the allegations, but my mind kept wandering away from me that month.

A year ago, I was also staring down a trauma anniversary myself. My family had abused me. My father then disowned me over a text message early September 2017. A childhood of psychological abuse had bled into a young adulthood of financial abuse and surveillance, and when I stood up for myself, everything came crashing down. When he texted me, the message started with me as an “ungrateful b*tch”, a reminder that I would always be just a woman to him, and worse, a troublesome one.

When Carol yelled, “I don’t even know who I am!” the moment reverberated in my spine. To recover from C-PTSD in any capacity means you oscillate from drowning in mud swamp to burning in a desert, for a long, long time. Your reflection disappears from you.

And that is why we need stories more than ever. We need to see ourselves somewhere, anywhere, so we can see a way forward. Especially when the newspaper stories can’t offer us anything. Especially when our tormentors erased us so we can only see ourselves in their eyes. Captain Marvel relayed a story about a ‘bad’ woman who wouldn’t just smile it away, who fought for the truth no matter how much it might hurt. So here’s to bad women like Dr. Blasey Ford and Captain Danvers. Here’s to having nothing left to prove, even to yourself.