Content warning: discussion of sexual assault; Spoiler warning for Carnival Row

When I first looked into Amazon’s new show, Carnival Row, after having been barraged with video ads on social media, what I read intrigued me. In its developmental stage Guillermo del Toro had been heavily involved, before having to leave the project due to his film schedule. The show’s general premise and aesthetic—a Victorian fantasy world centered around a Ripper-esque serial killer—reminded me of his sleeper gothic hit Crimson Peak. It advertised itself as topically relevant, its themes of political tension rooted in the world’s many mythological species. Carnival Row centers on Rycroft “Philo” Philostrate, an Inspector for the Constabulary tasked with finding the killer, and Vignette Stonemoss, a faerie refugee who immigrates to his city. They shared a romantic relationship years ago against the backdrop of a war in her home country. Advertisements touted the show as grounded in the titular neighborhood, echoing the crime-ridden streets of Victorian-era Whitechapel. As a devourer of true crime and historical mystery shows, Carnival Row sounded like a perfect new fantasy to binge.

What intrigued me most though was the promotion of Vignette Stonemoss’s pansexuality. Cara Delevinge, who is openly bisexual and genderfluid, plays the character and revealed Vignette’s sexuality a month before the show premiered. The quote, “I’m a pansexual fairy,” kept circulating throughout press articles, so I kept that in the back of my mind for a possible essay topic. I researched pansexuality to have a sense of that community’s culture, in case the show did its own research, like consulting Delevinge on queer representation.

Thinking about the show led me, as a writer, to consider monosexuality versus multisexuality and how they can be portrayed, especially bisexuality versus pansexuality. Their differences lie in gender and personal interpretation, and most people don’t think of pansexuality when they see a character attracted to more than one gender. Bisexuality is better known and understood, with a much longer history. The difference could have played out onscreen as the advertised political themes, specifically focused on the faerie immigrants, would allow room for nuance on gender interpretation and sexuality. Telling a story that highlighted a marginalized person could subsequently highlight systemic and daily issues that such a character would face.

Unfortunately, the show played into the trappings of Game of Thrones (GoT), ones familiar to readers of our site.

In many ways, this post is a response to my last article, which dealt with complex trauma from interpersonal violence and its connection to sociopolitical issues. (And this was not intentional at all — it was just something my brain pieced together without informing me until after the fact.) Captain Marvel succeeded because it zeroed in on its protagonist. It kept to a familiar and simple story rather than gorging itself on subplots and a large cast. Carol’s womanhood — and how it affected her interactions with the world and the world’s interactions with her — could not be extracted from the story. Though Vignette’s queerness came across clearly enough, neither she nor the writers connected it to the greater situation at hand. In the full interview, Delevinge explained that, “A lot of the things that weren’t written in the script, we made them so. Obviously, I didn’t say, ‘I want to be a pansexual faerie,’ but it made sense that all faeries kind of just love who they love.” It was not a topic for in-depth discussion. In the end, Carnival Row fails to fully distinguish pansexuality as distinct from other multisexualities because it fails to depict queerness as a distinct social and political identity.

I will dive into Carnival Row’s extensive problems later, but here is some foreshadowing fodder: One of its more politically-driven characters, Sophie Longerbane, works to sow chaos because it “creates opportunities,” reveling in the idea that she can torch the world and then mold the ashes as if they were clay. She also has an incestuous encounter at one point, practically in broad daylight. Yes, the show really pushed out a bastard of Batfinger and Cheryl. But she’s not the focus of this article, only a reference point, as the show’s very foundations in characters and worldbuilding crumble upon closer inspection. And those foundations include Vignette’s pansexuality and Carnival Row’s general queerness.

With all of that in mind, let’s take a look at bisexuality and pansexuality as orientations and their respective histories, then take a look at the actual show. Most of my work will pull from Dr. George Chauncey’s groundbreaking and fieldmaking 1994 book, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. His ethnography traces the multiplex world of gay men, outlining the neighborhoods along their racial, ethnic, and class lines, showing how queer cultures can develop within their environments. One of the most influential stereotypes was the fairy — the effeminate gay man who society saw as occupying a ‘third sex’. To avoid confusion, I will refer to Vignette’s species as “Fae” even though it’s the more broad nomenclature for non-human characters, preserving Chauncey’s text.

Lastly, in the preface to the 2019 paperback, he reflects on the explosion of queer theory since then as well as the birth of transgender studies, which happened a few years after his book. He acknowledges that his analysis overlooked transgender women. Due to availability, I used the 1994 version, so unfortunately the citations will not be as nuanced as today’s discourse, as we shall see.

Multisexualities

Monosexuality classifies the single-gender attraction of hetero and homosexuality, while multisexuality blankets bisexuality, pansexuality, polysexuality, and omnisexuality. Of these multisexualities, bisexuality and pansexuality are the most visible and in tension with each other. Sometimes accusations have been thrown at the bisexual label for ‘transphobia’ because of its perceived ‘two-gender attraction’. Others dismiss pansexuality for its perceived newness. Some Googling easily disproves these presumptions.

Known for its fluidity, bisexuality as a term dates back to 1892. It appeared in Psychopathia Sexualis, pathologizing multisexually queer people, before they reclaimed it in the 1960s. It did originally mean attraction to two genders, hence the prefix of ‘bi’, from the Latin for ‘two’. As Chauncey notes, it also came to mean “individuals who combined the physical and/or psychic attributes of both men and women[,] […] a bisexual was both male and female,” (p. 49) for a time at the turn of the century.

Bi-ness is further complicated by the difference between romantic and physical attraction, which split bisexuality into conjunctive and disjunctive types. Essentially, conjunctive bisexuality encompasses romantic and physical attraction to more than one gender, while disjunctive bisexuality only encompasses physical attraction. Scholar Hugo Schwyzer wrote in 2011 about this complexity, and though his work fails to account for nonbinary genders, it is important for understanding how complex bi-ness is:

Researchers on bisexuality have often noted that those who identify as bi often have that same heart/body disconnect that I experienced. In the 1860s, the pioneering sexual rights crusader Karl Heinrich Ulrichs wrote of “conjunctive” and “disjunctive” bisexuals. The former could be sexually and romantically drawn to both genders, while the latter could fall in love with just one sex while still lusting for both. Ulrichs claimed that “disjunctives” came in both varieties (some bisexuals could fall in love with their own sex but not the other; some could fall in love with the opposite sex but not their own. But in order to “qualify” as bisexual, disjunctives needed to have physical desire for both men and women.)

Schwyzer and Ulrichs’s take on bisexuality also fails to incorporate asexuality and aromanticism into their definition. Recent labels like ‘biromantic’ and ‘panromantic’ are ways for people to reconcile these different types of attraction, whether they identify more on the bisexual, pansexual, or asexual spectrum. Subcategories yield to more subcategories.

Nowadays, many bisexual people use long-time bisexual activist Robyn Ochs’s definition, which originates in the 2009 anthology Getting Bi: Voices of Bisexuals Around the World: “I call myself bisexual because I acknowledge in myself the potential to be attracted, romantically and/or sexually, to people of more than one sex, not necessarily at the same time, not necessarily in the same way, and not necessarily to the same degree,” (p. 8).

Her interpretation echoes the bisexual community’s self-determination going back decades. The magazine, Anything That Moves: Beyond the Myths of Bisexuality, released its debut issue in 1990 along with its manifesto: “Bisexuality is a whole, fluid identity. Do not assume that bisexuality is binary or duogamous in nature: that we have “two” sides or that we must be involved simultaneously with both genders to be fulfilled human beings. In fact, don’t assume that there are only two genders.”

In regards to history and culture, bisexuality has a long-held seat at the politically-minded table (though some of these people would now identify with pansexual if they had the term). For example, a bisexual woman named Brenda Howard, the mother of Pride, coordinated the first Pride parade in 1969 and then the one-year anniversary march the following year. In 1998, Michael Page created the tri-colored flag so the subcommunity could have a symbol separate from the ubiquitous rainbow flag. He pulled the pink and blue stripes from the bi-angles and added purple to represent the invisibility that comes with passing. (Page also encouraged Monica Helms, creator of the transgender pride flag, to come up with a design for her community.) Page, Wendy Curry, and Gigi Raven Wilbur also established the first Bi Visibility Day on September 23rd, 1999, partially because that was Freddie Mercury’s birth month. (Yes, Page is iconic and underrated in his importance to modern queer culture. Unfortunately he left activism soon after and has no interest in speaking to the media.) Other bisexual culture makers include the likes of Josephine Baker, David Bowie, and Lady Gaga. In film and TV, there has also been a recent trend in ‘bisexual lighting’ which pull from the colors of the flag, sometimes for characters who are explicitly bi.

In contrast, pansexuality has only recently entered general awareness thanks to Internet platforms like Tumblr and celebrities redefining themselves. The term goes back a century though. The word comes from Greek, ‘pan’ as in ‘all’, and implies a universality in sexuality that has transmuted every few decades. InQueery summarized pansexuality’s history, noting its origins in Freudian psychology:

A doctor named J. Victor Haberman criticized Sigmund Freud’s method of psychoanalysis, and unpacked one part of his theory, which was that “the pan-sexualism of mental life which makes every trend revert finally to the sexual.” […] In other words: Freud theorized that sex was a motivator of all things, hence “pan-sexualism.”

By the mid-1970s, ‘pansexual’ was being used to describe sexual orientation, as evident by a 1974 article from The New York Times. In 2002, a pansexual LiveJournal community made its first post, the term developing noticeable web activity five years later. The tumblr blog, pansexualflag, was created in 2010 by justjasper, and their design took off, becoming a worldwide rallying symbol for this partially not-so nascent community. They described their design in contrast to the bisexual flag, writing that, “Yellow makes it stand out from the bisexual colours, representing non-binary attraction, while the similar use of pink/blue (in a different shade) acknowledges the similarity of having attraction fall into the binary,” reaffirming our decade’s interpretation of the term.

In 2017, GLAAD defined pansexuality as, “a person who has the capacity to form enduring physical, romantic and/or emotional attractions to those of any or all genders.” When Janelle Monae came out as pansexual last year, the word became one of the most searched words on Merriam Webster for 2018. Other celebrities include Miley Cyrus and Brendon Urie, and in 2015, Cyrus’s coming-out also generated a spike in the label as a search term. Democratic Representative Mary Edna González is the first openly pansexual elected U.S. official. In terms of fictional portrayals, there are characters like Deadpool, Annalise Keating from How To Get Away With Murder, and the titular character from Lucifer. The world over, this community celebrates Pansexual Pride Day on December 8th and Pansexual and Panromatic Awareness & Visibilty May 24th. It will be interesting to see how pansexuality as an identity and as a community evolves through the next decade, one that will surely see even more upheaval along the lines of gender, sexuality, and gender roles. As Carnival Row stands now, it will not be contributing much to the furthering of pansexual culture due to its numerous problems in portraying authentic subcultures.

Foundational Problems

Carnival Row is rich in worldbuilding, but it’s kind of information that is cloying, lacking in complexity. The characters often drop references to a religious figure, faroff location, or day of the week. These details rarely go deep enough to provide insight into the different cultures or world. Take the show’s opening scene for example. A series of title cards explain the imperialism destroying the land of Tirnanoc, which I later discovered was the Fae continent. Vignette comes from the country of Anoun, forming the northwest highlands. The camera pans over Fae corpses caught in the barbed wire that had been strung through the treetops. Through the mist a group of Fae women run from attacking human soldiers, known as the Pact. The wire forms a net, preventing any Fae from escaping into the canopy, yet it doesn’t explain why they don’t fly in the first place. When you’re being shot at, you zig-zag. And if you have wings, you get any kind of altitude that you can.

The scene further undermines itself when Vignette appears on screen. She stops one of the Pact’s beasts from attacking another Fae, flying a little off the ground, as it gives her more maneuverability. It could be argued that the Fae wouldn’t fly near the wire, not wanting to risk being entangled, but large gaps exist between the threads. Large enough for a body. The Pact are also such good marksmen that they can hit moving targets in misty conditions, killing most of the Fae via headshot. With death a very real possibility, at least one person would use their wings to bolster their odds of survival. Later in the episode, Vignette explains the situation to her friend, Tourmaline: “I got word that a group was hiding out in the woods, waiting for a boat out. Heard they’d escaped from a camp of some kind. All women and girls. Little girls.” Her statement contradicts the Fae we saw — all young women. The characters never discuss the camp again or its possible purpose. Vignette’s lack of curiosity about her fellow countrymen, the ones left behind in Anoun, reveals the show people’s lack of curiosity. Though the show wants to market itself as politically relevant, it fails to honor the resilience of its marginalized characters offscreen, the ones that form the backdrop of Vignette’s world.

The more a story disappoints me, the more I nitpick, especially when it comes to language. Carnival Row’s terminology reflects the writers’ privileged, disconnected perspectives. As I watched the show, I struggled with the difference between ‘Anoun’ and ‘Tirnanoc’. In the first episode, Philo speaks with a surviving Fae witness, as he investigates a series of hate crimes. To connect with her and to coax more information from her, he talks about his time abroad: “You’re from Anoun. I spent some time in the Tirnanese highlands myself during the war.” The audience later discovers that Philo is half-Fae, his wings having been amputated when he was an infant, and he knows this himself, reflecting on his sense of peace while stationed abroad. His wording implies that Anoun is a region within Tirnanoc, and because he is half-Fae and loves their culture, he would not conflate a country with a continent.

Marc Guggenheim and Travis Beacham, the executive producer and co-creator respectively, discussed their fantasy setting for Den of Geek. Their comments displayed a superficial awareness of social issues: lip service dissonant with their scripts. For example, Beacham discussed the confusion over Tirnanoc as it’s discussed by the human characters:

Again, the humans lumping [the Fae] into, “You’re from Tirnanoc”, almost being like, “You’re from the Dark Continent.” Huge, huge place, with a multitude of ethnicities there. The Fae are similarly diverse and complex.

His statement aligns with all of the human characters’ dialogue except for Philo’s. That would be fine except Beacham also contradicts the Fae he’s supposedly speaking for. Towards the end of the same episode, Tourmaline and another Fae discuss Vignette’s situation, and the other Fae points out that, “[Vignette] survived seven years in Pact-occupied Tirnanoc.” So not even the Fae distinguish their country from the greater continent. It confuses viewers about the geopolitical borders, and it erases the Fae’s cultural specificity, their dialogue echoing the dominant group for no apparent reason. It fits into what Chauncey refers to as the “discourse of the elite,” and though he applies it to “official maps of the culture [that] [inscribe] meaning in each part of the body,” (p. 26), citing examples like medical literature, I apply it to the show people’s interpretation of their work and Carnival Row’s geography. Such superficial, thoughtless elements of worldbuilding form Carnival Row, and it only weakens as the viewers glimpse more subcultures.

Queer Representation

Considering this, the show takes little interest in depicting and empathizing with its queer characters. Delevigne confirmed that all faeries are pansexual, yet all but one of the Fae relationships could be interpreted as straight if viewers didn’t know about offscreen texts. (We only see Philo’s Fae mother with his human father, for example.) When Vignette arrives in the Burge, the human city-state, and settles in the titular neighborhood, she immediately seeks out Tourmaline, whom she considers her ‘best friend’. The show makes it clear that they shared a romantic relationship before Vignette and Philo fell in love, as the women discuss their history and enduring friendship. This exchange takes place in two episodes. The writers still incorporated queerness, but in such a way that Vignette’s attraction, at first glance, fits into the binary attraction associated with bisexuality. She never discusses her romantic history or her feelings about her sexuality. The Fae never discuss the Burge’s homophobic culture and how it could impact their own relationships.

Her personal history remains relatively closed off to viewers, which starkly contrasts to Philo, the leading man. The characters were equally billed, as evident by promotional materials. Though Philo’s parentage drives the mystery, it also reflects the show prioritizing him as the protagonist and Vignette as his love interest. They spend most of the narrative apart, but her character culminates in her forgiving him for leaving her. Her backstory remains limited to the flashback episode that covers their original relationship.

Indeed, Carnival Row only touches upon one explicitly queer couple. When Philo investigates the second murder in episode 1×05, that of his former headmaster and father figure, he discovers the man had shared a romantic relationship with Dr. Morange, a doctor and volunteer coroner for the Constabulary. Morange’s solitary minutes onscreen give no depth to the expected queer subculture in the Burgue. Though Chauncey writes about gay men, his analysis can be broadly applied to queer resistance and communal ties, noting that, “Gay men had to take precautions, but, like other marginalized peoples, they were able to construct spheres of relative cultural autonomy in the interstices of a city governed by hostile powers,” (p. 2). The silence around Morange’s character in-show — the lack of close friends and people to grieve with — reinforces “the myths of isolation, invisibility, and internalization [of shame],” (p. 2). Homophobia and anti-queerness stigmatized people and many suffered from shame, but as Chauncey reveals, this disservices the complexity inherent to human beings. The fairy stereotype, the one that I mentioned earlier, sparked in New York’s culture and imagination, its hypervisibility evidence that many gay men embraced their differences from the dominant culture and took pride in themselves.

While secrecy definitely permeated all queerness, and still does the world over, even in shadows people could still forge chains of community, the found family of adulthood, especially in urban landscapes. As immigrants bring their cultural touchstones to their homelands, so do queer people pull from their cultural spheres, in order to filter a world through their lens. By building a culture, queer people can communicate their experiences and can provide lifelines to struggling members, hence the importance of representation on and offscreen. This comes out most clearly when considering the history of the closet metaphor, which dates only back to the 1960s (p. 6):

Like much of campy gay terminology, “coming out” was an arch play on the language of women’s culture–in this case the expression used to refer to the ritual of a debutante’s being formally introduced to, or “coming out” into, the society of her cultural peers. […] A gay man’s coming out originally referred to his being formally presented to the largest collective manifestation of prewar gay society, the enormous drag balls that were patterned on the debutante and masquerade balls of the dominant culture and were regularly held in New York, Chicago, New Orleans, Baltimore and other cities. […] Gay people in the prewar years, then, did not speak of coming out of what we call the “gay closet” but rather of coming out into what they called “homosexual society” or the “gay world,” a world neither so small, nor so isolated, nor, often, so hidden as “closet” implies. (p. 7)

Only mere pages into his book Chauncey shatters the myth of the closet, demonstrating how that when the spatial is reframed, so is the psychosocial and the sociopolitical reframed. If queer people take up enough room to form their own world, it allows room for a political narrative. It creates a continuum; it crushes the conservative argument that crumbling gender norms and unfamiliar terminology are only a product of today’s generation.

In regards to Morange, his character exists in solitary confinement, his coming-out confined to the single episode. It ends with his violent murder, and neither the narrative nor Philo discuss the affair again, besides a reference at the beginning of the next episode. The storyline mirrors the camp survivors’ abandonment. Morange’s coming-out also comes about because Philo finds him in a brothel bedroom, privately mourning his dead lover, as they rendez-voused there every week: “When you’ve lived with a secret as long as I have, you’d be amazed what you can hide. Still, there’s always the shame. […] We only had one night a week when we could be who we truly were.” Based in a bedroom, the scene functions as an extension of the closet, extenuated by the sexualized setting and low lighting. We never see a queer human character again, and as I mentioned earlier, the Fae’s queerness is only explicit with Vignette and Tourmaline.

Imagine how powerful it would have been if after coming out to Philo, Morange met up with queer friends, allowing him space to fully grieve with people who know him in his entirety. They could have discussed their various struggles and triumphs as citizens of the Burgue, details that could connect humans to the marginalized groups over in Carnival Row. Bigotry is bigotry, after all. If the show didn’t have the time for all of that, it could have done something simpler. Chauncey notes that gay men, at the turn of the century, wore red ties to subtly communicate their desires to those in the know. A similar symbol could have been referenced in dialogue, and then when Philo discovers Morange, he sees Morange wearing a physical testament to his love and his true self. Rather than drag viewers through parliamentary meetings, filled with background faces we won’t remember or need to, the show should have zeroed in on the politics in the characters’ lives. Carnival Row tackles this a little when Vignette sees her people’s beloved books on display in a museum, calling back to real-life colonial exploits, but it’s minimal for a show claiming political awareness.

Reinforcing the myths of the closet serves to depoliticize queer activism and resistance, as it declutters a long and oscillating history divided by issues of class, gender, and race; reinforcing the tension between assimilative and liberatory politics. In the case of Morange, he could have served as a vehicle to bring the public sphere into the private.

With all of that in mind, Carnival Row’s lack of community and lack of characters’ reflections on sexuality bleed into the understanding of gender. Bisexuality and pansexuality are more similar than not, coming down to individual preferences. Their definitions imply that bisexual people feel attraction differently depending on the gender, while pansexual people feel attraction equally to genders because they feel attraction regardless of gender. To represent that universal desire requires a more nuanced, specific take, such as a character discussing their preference for emotionality rather than physicality. In New York City a hundred years ago, gender presentation shaped society’s perception of a man’s sexuality. So long as he presented masculine and played the “man’s role” in sex acts, he would not forfeit his status as ‘normal’. He would not be seen as any variation of ‘queer’, whether it fell into the straight-gay binary or not, like pansexuality:

[This study] argues that the construction of male homosexual identities can be understood only in the context of the broader social organization and representation of gender, that relations among men were construed in gendered terms, and that the policing of gay men was part of a more general policing of the gender order. (p. 28)

Feminine gay men as fairies ‘replaced’ women in homosexual interactions, their identity and gender specifically conflated with ‘tough girls’ and sex workers (p. 61). Society defined male sexuality as phallocentric, so his ‘release’ superseded the person who caused it (p. 85). The heterosexual-homosexual binary had not yet taken root.

In a video essay, YouTuber ContraPoints examines cis, hetero men’s sexuality. She zeroes in on its rigidity, explaining, “[T]his hypermasculine hetero man code is basically an ethics of purity, a kind of kosher law governing straightness, and the Is This Gay? game is its theology,” (t. 33:59-34:29). Purity reinforces binarism because it implies that purity is rare; it contrasts against the ‘impure’. With the backlash against visible queerness after World War II, and the creation of the modern American straight-gay binary, society inverted the phallocentrism that had opened men to explore queer attraction. To be impure is to be an Other.

On Carnival Row its most visible and frequented location is the Tetterby Hotel, the Fae brothel where Tourmaline lives and works. Vignette also shelters there for most of the series. They never discuss their gendered experiences, how their very existence threatens the Burgish binary and its imperialistic, conquer-or-be-conquered culture. And gendered violence permeates their world, and it intersects with their species, so it inherently intersects with their sexuality. The Fae’s queerness is an open secret, hence the accusation that they bring “vices” to the Burgue, reinforced by many Fae working in the sex trade. When Philo conversed with that Fae witness, she mentioned being called, “a Pix whore,” before being attacked. The term ‘Pix’ is a Burgish slur against her species, and it modifies the gendered and classed insult of ‘whore’ as it represents her innate deviation from the pure ‘norm’. When Vignette’s employer attempts to rape her, he also calls her a ‘whore’. In patriarchal cultures, the woman is the innate Other, no matter how privileged she is in society. Any association with her taints a person, hence the fairies being disparaged by queer and non-queer people alike because of their feminine characteristics. The stigmatization of queerness and sex work are intertwined historically and culturally, especially due to the intersections of gender, class, and race.

Overall, Carnival Row presents no political discussions of queerness, only individuals and individual relationships in the shadows. Intersectionality as a theme never emerges. The show stresses that Fae can ‘pass’ as human if they undergo certain operations, but the show never addresses the psychosocial characteristics like gender and sexuality. Because all Fae are queer, they would still be persecuted for their sexualities even if they were accepted for their species, and women would still be degraded as ‘whores’. Assimilation isn’t a real option.

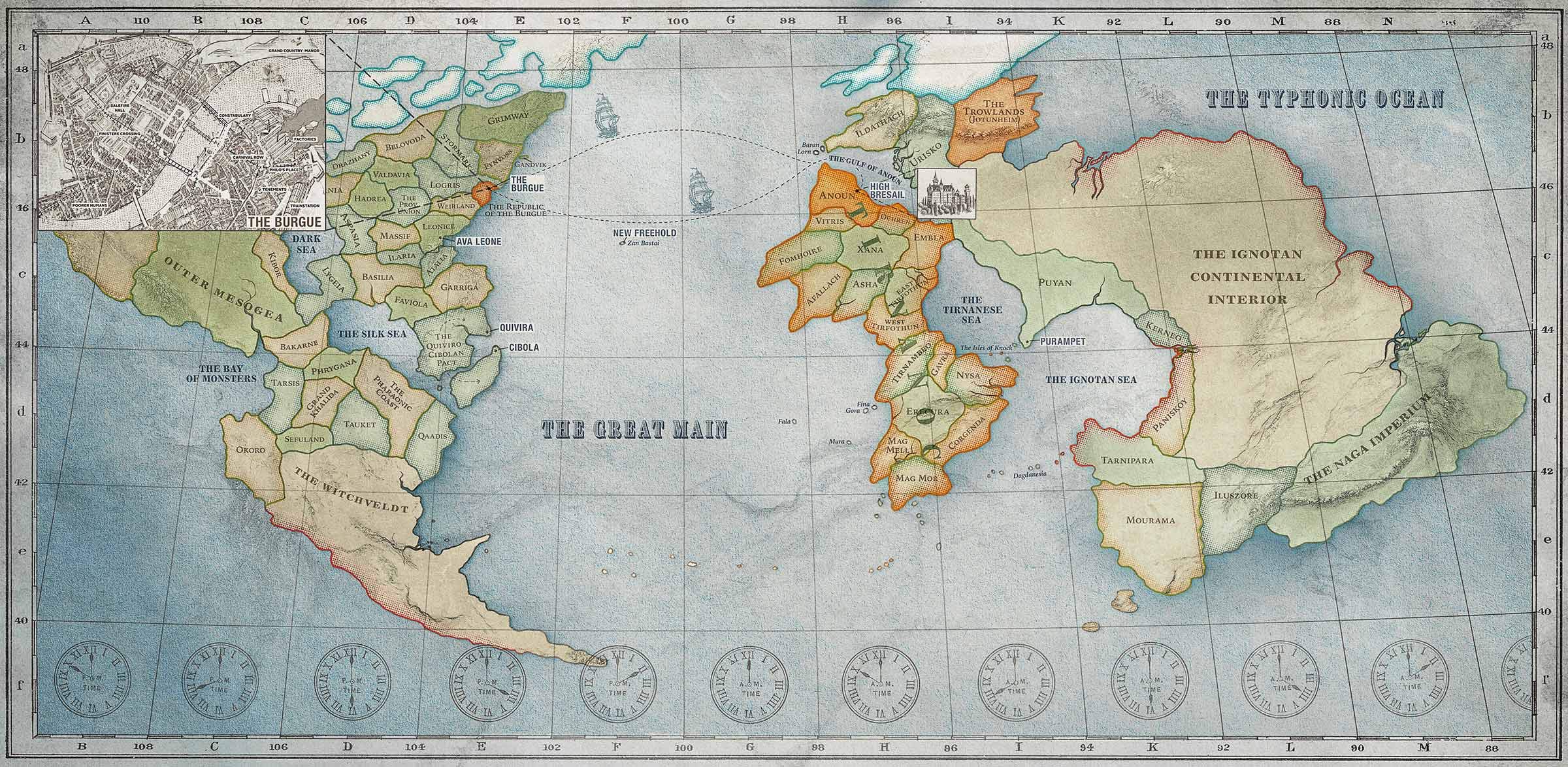

As I also mentioned earlier, Chauncey wrote his book as an ethnography of New York’s culture, mapping out the city and the intersecting lines of ethnicity, class, race, and sexuality. Geography reflects and reinforces certain cultural beliefs, and as a tool cartography is often used by the elite, hence the infamous Mercator projection map and its connections to colonialism. Cartography is a rich phenomenon in speculative fiction, and authors can use maps of their worlds to destabilize the reader’s conception of normal. (I originally considered this subject for my Captain Marvel article, but realizing how long my initial draft had become, I cut that section and will save it for its own article.) In her article, “If you can see a thing whole”: Planetary Cartography and Global Ontology, Amelia Z. Greene describes the graphic as potentially subversive:

[The author] offers such encounters between alien mindsets, and the ways in which their modes of understanding are expressed linguistically and cartographically, as evidence of the particular strengths of the genre of speculative fiction, which provides a means of investigating and critiquing forms of knowledge-making like global cartography by literalizing the alien: the being with whom we can communicate, but for whom the universe is organized differently (p.17-18)

Though Greene focuses on science fiction, her insight applies to fantasy as a whole as it also falls under the umbrella of speculative fiction. Amazon Studios released a fictional map of the world of Carnival Row, and the show’s take on its own geography undercuts its premise. As the creators used the language of the Burgish human and implanted it into the Fae, so do they also ignore the Fae’s spatial reality.

The map highlights the world rather than the city or neighborhood, a poor imitation of GoT. The title ‘Carnival Row’ refers to a specific neighborhood, yet the map labels in broad strokes, even when zoomed in. In the small window at the top left corner, viewers can see a bird’s eye view of the Burgue, Carnival Row a collection of houses and streets. Noticeably, the map acknowledges Philo’s lodging while ignoring Tetterby Hotel, the only named location on Carnival Row and Vignette’s future home. We never see Vignette become lost in her new environment; we never see her reference a map nor ask for directions. The setting disappoints fantasy fans as it lacks specificity — including the brothel, I can only list three non-residential locations in Carnival Row separate from the criminal Underworld. Our generation grew up with the likes of Harry Potter exploring Diagon Alley, our faces contorting in amazement like Harry’s as he wandered past various shopfronts that informed us about wizardly priorities and daily life. These small details in a story accumulate and can develop narrative interest, planting seeds for Chekov’s guns and the like.

Though we see middle-class human characters, such as Philo’s landlady and the constabulary force, the map and the show give no insight into their cartographical identities, how they might be shaped by their surroundings. Besides Carnival Row, the map only references another neighborhood: Finistere Crossing, seat of the upper-class. It’s situated near Baelfire Hall, governmental seat of the city, while Carnival Row faces the Constabulary, the police a sociopolitical force that degrades the Fae residents and carries out the whims of the powerful. Chauncey describes the relationship between geography, class, and sexuality in terms of spatial awareness:

Middle-class ideology frequently interpreted actual differences in sexual values and in the social organization of middle-class versus working-class family life that grew out of their quite different material circumstances and cultural traditions as evidence of working-class depravity. […] In this ideologic context, the red-light district provided the middle class with a graphic representation of the difference between bourgeois reticence and working-class degeneracy. (p. 36)

With no thought to Carnival Row’s geography comes no thought to the cultures that developed within its boundaries. In terms of GoT, its international map at least fit with its epic scope as violent political fanfiction. My paperback copy of A Clash of Kings, the second book in George R. R. Martin’s series from which the show was adapted, includes a map of King’s Landing, the capital. The city has its own slums known as Flea Bottom, and its graphical representation consists too of houses and streets, but Flea Bottom is not the title of the series. The book series’ title, A Song of Ice and Fire, speaks to the stories’ complementary narratives and historic nature. The title ‘Carnival Row’ implies a place of migrants constantly in flux — bright colors and fantastical imagery. Chauncey even described the fairies of New York in terms of fluctuation because, “the very theatricality of the fairies’ style not only emphasized the performative character of gender but evoked an aura of liminality reminiscent of carnivals,” (p. 80).

Speculative cartography has power and psychological resonance, considering the prevelance of GoT’s map in pop culture. Seats of power like the Red Keep in King’s Landing, as they loom over the masses, remind readers about the hierarchy and discourses of the elite. On the other hand, secretive, self-contained settings like Diagon Alley, removed from the London of Muggles, offer viewers a niche ensconced from the ‘pure’ façade of respectability and normalcy. I hope Carnival Row respects that resonance and truly develops its own places of meaning, not only for viewers but for its characters.

Conclusion

Representing pansexuality comes from thoughtful, well-informed intent. Vignette as a pansexual leading lady disappears into a show bloated on fantasy tropes codified by GoT. These include superficial depictions of discrimination and overdrawn parliamentary meetings, shaped by the machinations of the privileged. In some ways, Carnival Row takes its cues from current issues more than it realizes. In today’s world, the depoliticization of queerness manifests in different ways, reflecting how intersections of class, race, and gender still separate members of a community. This includes the corporatization of Pride and the rise of homonationalism, an ideology that combines gayness with white nationalism.

Infuriatingly, there was also the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall this summer, a rebellion rooted in the fury of queer women of color, some of whom were trans women that worked as sex workers. On June 28th, a black trans woman disrupted a drag show in order to draw attention to the violence that plagues her community. Trans women of color are murdered at a disgusting rate in the United States, and she pointed out the white, gay community’s complacency. Members of the bar ranted about calling the cops and only allowed the woman twelve minutes to speak. Let me repeat that: on the anniversary of the Stonewall riots, queer people threatened to call the cops on a trans woman of color.

That all being said, I don’t want to leave readers on a negative note. Something empowering for the queer community also came out this summer. Thanks to the work of archivists and the Internet, the Asexual Manifesto was unearthed from the archives of the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance. The Manifesto dates back to 1972, reaffirming that asexuality existed before the Internet and that it existed in political terms. The asexual community never solidified with strength after the feminist movement of the 70s, but it was built thanks to the connectivity of the Internet, in many ways mirroring the sprawling New York streets and the safe anonymity of dark clubs and bars. I am betting now that pansexuality has a similar lost history buried in newspapers, archives, and the everyday writings from ordinary people just living their lives. As a landscape is mapped, so is history. It’s time to get a compass.