Content warning: discussions of child abuse and sexual assault

Introduction:

Back in August, Disney’s The Owl House released its highly anticipated prom episode, and afterward I found myself wanting to cry into my glass of wine. I was thinking about how I had seen two girls dance together like it was simultaneously a normal occurrence yet the most extraordinary thing in the world. That dichotomy — normalization contrasted against valorization — fascinated me. Contemplating my queerness and seeing it on screen helped me better understand my position as a survivor of child abuse, why we consume stories the way we do. So of course I wrote a few thousand words on the topic.

Privileged identities decide what kinds of representation ‘matter’ in the first place, and that includes trauma as a marker of identity. To be clear, I do not mean survivors of trauma are defined by victimhood. Rather, surviving trauma changes a person’s relationship with the world and with themselves, and this change has ramifications on a political and cultural level.

Both an adult survivor of child abuse and a queer person, due to suppression and secrecy, can experience a similar loss of childhood. I processed these parallels after I watched The Owl House’s special prom episode. How I differ from those with what some call ‘non-survivor privilege’, even if that person and I both experience queerphobia. Subsequently, the follow-up to this article will focus on The Owl House and why it is so validating as a story for queer girls, how that has parallels to the psychology of trauma.

Even though discussions around representation permeate pop culture, the conversation still lags when considering depictions of trauma survivors. This reflects a general silence on non-survivor privilege, which ties into the relationship between interpersonal trauma and politics. How non-survivor privilege affects trauma representation and its authenticity, its integrity.

Non-Survivor Privilege — An Invisible Identity:

Trauma covers a broad range of experiences, though non-survivor privilege refers specifically to interpersonal trauma such as child abuse, sexual assault, and domestic violence. When a person traumatizes another, that is politics in action, distilled to core elements as the assault(s) come with loaded power dynamics, layers of socialization pressing in. I will be focusing on depictions of child abuse for this article because it has parallels to the queer experience: child abuse is based on a person’s formative years and the specific effects on their socialization. But before diving into this topic, I want to make one thing clear. Interpersonal trauma is not the same thing as being queer. One is directly about surviving violence, the other a socially-understood identity that historically has been at risk of violence due to outside prejudice. The two can overlap — many queer people survive toxic childhoods — but they can also be mutually exclusive. As always, I pull from Judith Herman’s 2015 Trauma and Recovery reprint, my trauma studies bible.

To begin, the term ‘non-survivor privilege’, as far as I could find, dates back to a 2008 essay by Jennifer Kesler. When you google that phrase directly, almost nothing comes up, mostly references to Kesler’s post. Her post articulates a specific rage of survivors of interpersonal trauma experience, and for me, who had to leave her family of origin, Kesler also articulates a profound alienation from mainstream society. She explains, “Once you survive abuse or violation, you have a knowledge of the human capacity for nastiness that others around you don’t share. It is your duty to keep them blissfully ignorant at the expense of your own soul.”

Her comment aligns with observations that experts like Judith Herman have noticed; she has compared trauma survivors to immigrants entering a new culture, psychological expats (p. 196). (When it comes to this cultural shift, Herman also stresses that it’s intense for survivors like battered women and abused children.) Survivors of long-term trauma leave behind an entire way of being, and they have to reconfigure their socialization, their self-image, and their understanding of the world. This transition comes with almost no structure in place. From my experience, the cycles of grief feel almost meaningless without a culture to validate that grief in the first place.

Those scant Google pages that I mentioned earlier? They reveal the dearth in discourse around non-survivor privilege and reveal how we frame it as a problem within specific social groups. But for survivors of child abuse, it isn’t just a women’s issue or race issue or queer issue. A discriminatory parent may use those prejudices to further harm a child, but the relationship goes deeper into the heart of power dynamics.

The privilege comes from non-survivors being able to live in denial about our culture of abuse and how that affects their place in society. Those with non-survivor privilege tend to victim-blame, deny the existence of abuse, and accuse the survivor of lying, of playing the victim, and thus further traumatizing the individual. If one acknowledges the horrific statistics of the abuse of women and children, for example, one must then acknowledge how deeply patriarchal our world is. How much not being abused lies in luck. The vulnerability in knowing it could happen to anyone. Subsequently, Kesler elaborates that non-survivor privilege ripples out into oppressive structures like misogyny, racism, and classism: “As soon as you decide it’s okay for some people to carry double and triple burdens so that others may carry nothing at all, you have decided abuse is pretty neat and you’re all for it.”

With that in mind, the non-survivor privilege extends beyond a psychological reality. There exists a lack of material protection, a lack of legal infrastructure, for survivors like me. Children have few rights in the United States, and the issue compounds when adult survivors start to repair the damage, having to start over and reparent themselves. Adult survivors often deal with financial struggles, lacking an intergenerational support network and safety net, the ability to call up a relative. They usually can’t go to the justice system for restitution. The legal code means jack shit when it comes to psychological abuse, and corporeal abuses usually don’t leave court-approved evidence. Regardless, all of these issues intersect across the body. From a medical standpoint, therapy is an obvious cost in time and money. Research also shows a direct link between child abuse and chronic illnesses, such as autoimmune disorders, because the toxic levels of stress damage the body in its formative years.

Abusive parents have also been known to infantilize their young adult children and thus sabotage their early steps into adulthood. In 2018, my home state of Delaware became the first state to fully ban child marriages, and as one representative noted, children are kept in legal limbo: “[T]hey cannot file for divorce, utilize a domestic violence shelter, apply for a loan or open a credit card. They cannot enter any legal contract, but until this bill was signed they could be married as a child without any way of escaping an abusive marriage[.]”

The silence of my abuse was compounded by a society based in silence, and this silence ripples into the media we consume. The language we aren’t taught to recognize, to speak.

Pop Culture & Its Poor Track Record with Trauma:

As I mentioned earlier, silence and denial form a large part of non-survivor privilege. That leads to downplaying, and sometimes outright erasure, of abuse. I compiled some examples of child abuse in media, taken from the top of my head, that reveal this pattern of privilege, as these stories are usually depicted by secure straight white men. The least likely group to experience any form of oppression or interpersonal violence.

For decades, Homer Simpson has choked his son without any examination or condemnation from the show. Family Guy has similarly perpetuated child abuse, escalating as Meg has morphed from a character into the Griffins’ punching bag. There’s also the frustrating TV trope of the neglectful and/or abusive father being redeemed solely on the basis that ~ he secretly cared all along!~ And in the most recent season of Stranger Things, the Duffy brothers practically retconned Billy Hargrove’s psychological abuse of his younger stepsister, Max, as his tragic possession and heroic sacrifice took precedence over a girl’s trauma.

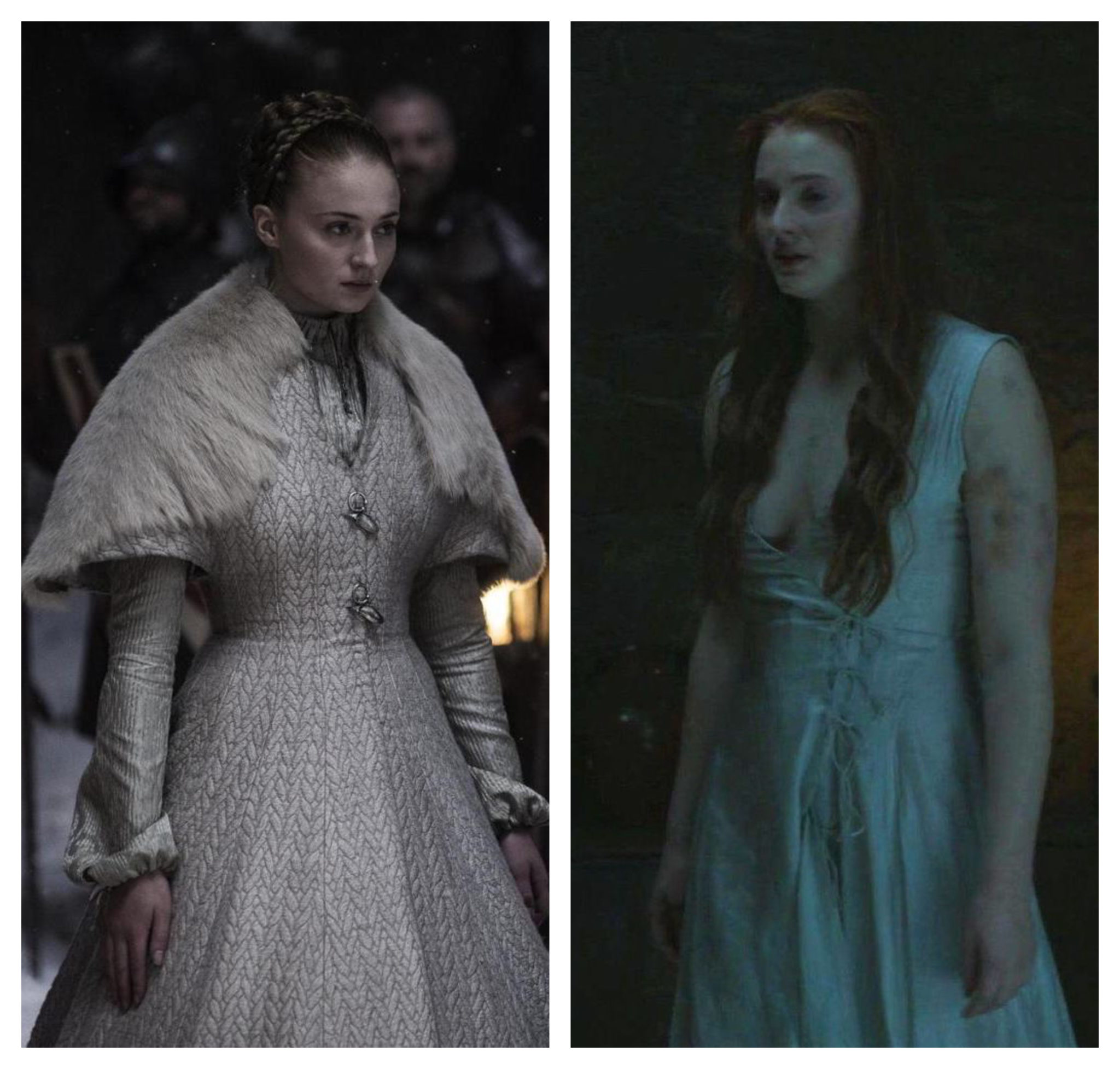

In addition, there exists this intersection between youth, (white) womanhood, and femininity when it comes to media fetishizing abuse victims. Game of Thrones (GoT), a long-time darling of criticism here, is guilty of this. The show version of Sansa Stark endures psychological and physical abuse from her fiancé, mad king Joffrey, for two seasons while still a young teenager. Her character arc generated controversy — to say the least — when the writers then married her to the sadistic serial killer and rapist Ramsay Bolton. The Powers That Be preceded to sexualize Sansa Stark’s repeated rapes by her husband, giving her tousled sex hair and ‘tasteful’ bruising, leaving her face intact. She even sported lipgloss. Viewers reinforced this when artist Andrew Tarusov released pin-up illustrations of several female characters from GoT. Tarusov drew Sansa in her Winterfell wedding dress, the one that Ramsay ripped off her when he raped her. So, a man drew a sexualized image of a sexual assault survivor, wearing the clothes preceding her attack, and of course, the public ate it up. And though the image didn’t go viral, Tarusov also drew another GoT rape survivor, Gilly, half-naked, wearing a T-shirt that said, “Be My Daddy.” Viewers meet this character while she’s married to her father, having been impregnated by him. Her father had routinely forced his daughters to become his wives and bear him more daughter-wives. Got to love incest being a punchline. Thanks, patriarchy.

Similarly, comic book artist J-Scott Campbell drew a series of sexualized Disney Princesses for several calendars, the FairyTale Fantasies collection. The 2011 calendar included ‘Cinderella rag dress’ as the March header, and the image depicts Cinderella in her rags from the beginning of the movie. Campbell drew her scrubbing the floor so as to justify depicting her on her hands and knees, looking up off-page with glistening, childlike eyes. Echoing Tarusov’s design choices, Campbell drew an abuse survivor in the clothes she wore while forced to live as an indentured servant in her own home because of her abusive stepfamily.

Though neither Sansa Stark nor Cinderella were prepubescent in these moments, their abuse began as children and their designs stressed their youthfulness. In terms of Sansa Stark, that season she went from wearing a black vampy dress screaming cleavage to a demure white wedding dress and cloak that conveyed purity. Cinderella’s look included accentuated curves and a girlish pout, her clothes, and physical act a reference to the lower class level that makes her even more vulnerable in terms of gendered power dynamics.

In terms of non-survivor privilege, the Cinderella fairy tale also reveals how women dismiss the abuse of other women so long as they aren’t being beaten by a man. Feminist discourse often frames Cinderella as a passive woman waiting to be saved by a rich man rather than a young woman surviving abuse. The stories usually reference physical neglect and psychological and financial abuse, but the key is that the stepmother instigates the abuse. Because we rarely see Cinderella riddled with bruises and entrenched in gender politics, we can dismiss her mistreatment for what it is. (This is why Ever After with Drew Barrymore remains the most valid Cinderella film since it actually gets abusive dynamics right while still being an uplifting movie.)

Of course issues like race, class, and sexuality factor into non-survivor privilege and the depiction of interpersonal trauma like child abuse. (Campbell’s art deserves skewering for how he depicts princesses of color alone.) This is a complex topic, one that has been rarely discussed. I only cited these examples so as to show why so many representations are alienating, invalidating, and sometimes triggering for survivors. And that there exists a long history embedded into modern pop culture.

Representing Trauma Right & Intersections with Queerphobia:

So… what the fuck does this all have to do with being a Gay (™) and The Owl House?

Well, watching that show helped me to comprehend the emotional rollercoaster of good representation and why it is such a rollercoaster to see oneself portrayed authentically in a story. Due to how people experience child abuse and how queer people understand themselves, similar psychological mechanisms occur. I haven’t found any research on this connection, but I know it exists because I am living it.

For an abusive person, all the world’s their stage and their partner and children merely players. Abusers tend to be narcissistic and expect the family to present normalcy to the outside world, as well as to each other. Thus a traumatic childhood buries an individual’s authentic self, and survivors often emerge with a shame complex and warped identity, internalizing their abuser’s crimes. Judith Herman frames this disconnected identity as partially rooted in toxic performativity (p. 105). As another writer put it: “You’ve spent so much time suppressing your real self, from your emotions to your reactions, to deal with the onslaught of your parents that you haven’t had a chance to pay attention to your own development.” Even into adulthood, survivors carry this scared, desperate-to-please inner child.

Recovering from childhood trauma requires meeting this inner child and peeling back the layers of conditioning. Media factors into this because the art that we turn to, for better or for worse, factors into how we see ourselves. The leftist adage ‘Representation matters’ rings true for all marginalized people as fiction has been neurologically proven to improve a reader’s empathy. Seeing elements of one’s own trauma represented with care and thoughtfulness can help a person develop empathy for themselves. External validation makes it easier to forgive oneself and helps to wash away the stigma that comes from victim-blaming.

Earlier this year, activist Alexander Leon had a tweet go viral, as he described a core part of the queer experience: “Queer people don’t grow up as ourselves, we grow up playing a version of ourselves that sacrifices authenticity to minimise humiliation & prejudice. The massive task of our adult lives is to unpick which parts of ourselves are truly us & which parts we’ve created to protect us.”

His observation echoes the double self that childhood trauma survivors must unpack, the existential crisis based around performing. The hidden nature of trauma and queerness means they’re a bit different from the political nature of other identities, like cisgender and race, which largely are visible from the get-go and are more socially connected to larger traditions. (I know that this double self manifests in race issues, such as code-switching, but that’s not something I have personal experience with.) Unpacking the experience of trauma and unpacking the experience of queerness are similar processes of self-reflection and working away shame.

Both processes are about waking up to a more authentic self and the grieving related to that. Both processes hinge on community integration since it was a community that was denied to those people. Coming out often entails losing longtime loved ones, while rebuilding a new support system. Coming to terms with child abuse, and vocalizing against the perpetrators, tends toward a similar social earthquake.

Relatedly, survivors of child abuse tend to have a complicated relationship to media. Sometimes, positive stories about loving families and easy resolutions can be as triggering as an actual abuse scene. It sounds counterintuitive, but it stems from the psychological upheaval and cognitive dissonance Herman frames as a type of immigration. The reminder that you will never have a mother to call when things get hard, a father who claps you on the back with pride. From a material perspective, the lack of stable parents with unconditional love means that adolescence and adulthood intersect more often than not. Because parents deprived them of a safe environment, survivors of childhood abuse struggle with issues related to healthy development — psychologically, socially, materially. They have to start over and play catch-up with those who had a support system already in place. And that doesn’t include the mental health issues that long-term trauma often generates.

Queer people similarly struggle with a delayed adolescence as discrimination and cisheteronormativity tend to keep them from living out their authentic selves. Dating, sense of style, dreams about adulthood; these all get pushed back. And with these delays from adolescence, queer people lean into that chosen family for guidance. This absence in childhood and in our coming-of-age factors into our relationship with representation. Cinema has a history of burying its gays, queer baiting, and/or depicting queer people as depraved predators. Seeing ourselves reflected back as normal people worthy of love, which clashes with so much messaging we’ve internalized, can cause some cognitive dissonance to say the least. Sarah Fonseca summarized this relationship well when eulogizing lesbian and music icon Lesley Gore:

“People of all sexual orientations inherit a useful first-aid kit of platitudes from their mother figures[.] […] But when you’re gay, a mother can only teach you so much about navigating the messy world of your own desires. This is one of the minor tragedies of lesbianism: We often have to seek out advice about how to figure out our identities elsewhere. This “seeking out” is why lesbians still watch The L Word years after its finale; why so many young queers talk about the internet like it’s a favorite aunt; why lives like Lesley are worth the space in our public and personal archives. We should be able to consult with and see ourselves in our gay grandmothers — witness how they survived.”

Overall, childhood trauma survivors and young queer people lack personal guides into adulthood, and so they have to seek out mentors and role models to make up for their early isolation.

Conclusion:

For her book Willful Subjects, Sara Ahmed wrote, “A desire for a more normal life does not necessarily mean identification with norms, but can be simply this: a desire to escape the exhaustion of having to insist just to exist,” (p. 149). That sentiment applies when considering meaningful representation and how it shapes our perspective on marginalized people, people who have been shamed one way or another. Hopefully, creators with non-survivor privilege will do better by survivors of interpersonal trauma.

To hear my thoughts on The Owl House and queer representation, check out my article on Thursday!

Images courtesy of Pikrepo and HBO Entertainment

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!