Creator Corner: Interview with Ji Strangeway, Author of Red as Blue

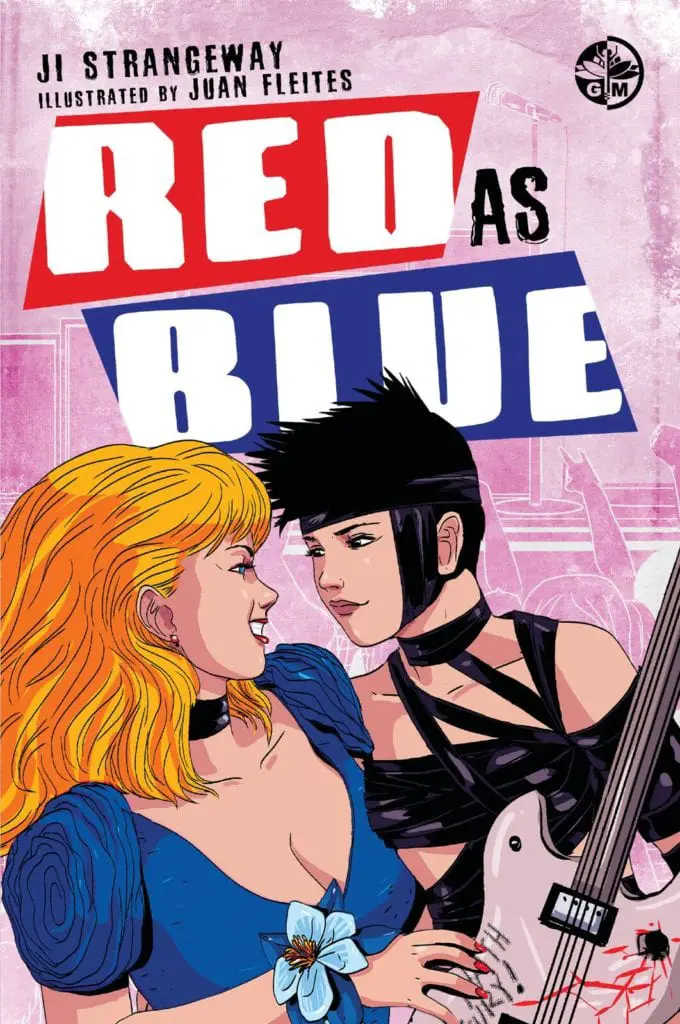

This past month has been unexpectedly refreshing creatively, and I’m so excited to offer you all another new installment of my Creator Corner series, where I sit down and talk with original content creators about their work. Fresh on the heels of my interview with writer, actor, and author of the graphic novel Journey to Gaytopia, I was given the opportunity to talk with Ji Strangeway, film director, writer, poet, and author of the soon-to-be-released hybrid graphic novel Red as Blue.

This past month has been unexpectedly refreshing creatively, and I’m so excited to offer you all another new installment of my Creator Corner series, where I sit down and talk with original content creators about their work. Fresh on the heels of my interview with writer, actor, and author of the graphic novel Journey to Gaytopia, I was given the opportunity to talk with Ji Strangeway, film director, writer, poet, and author of the soon-to-be-released hybrid graphic novel Red as Blue.

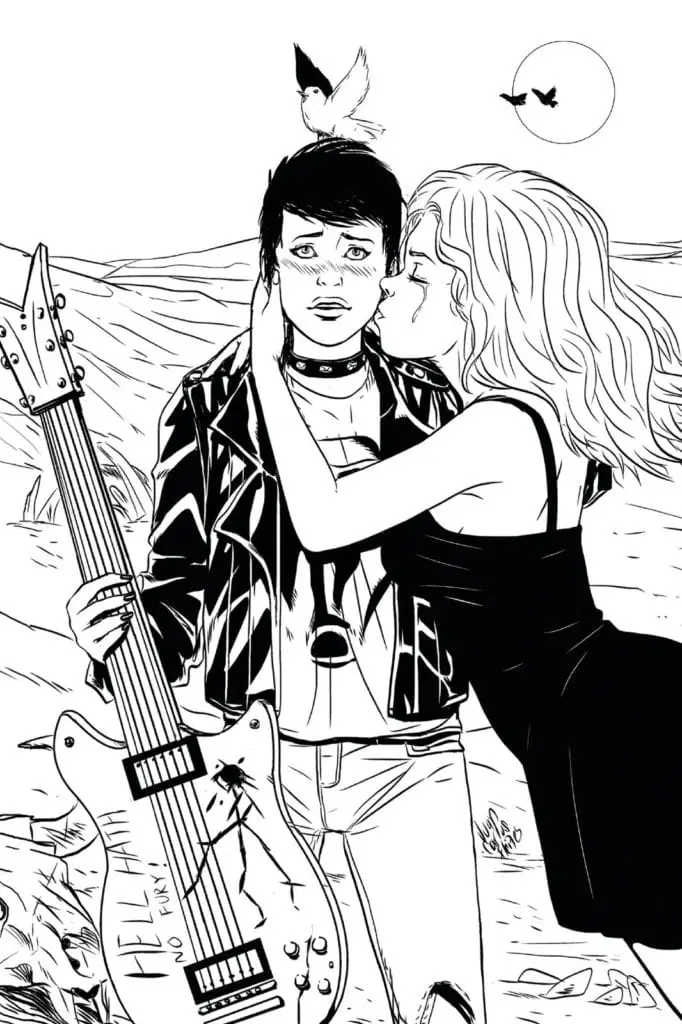

Her debut novel, Red as Blue is set in a fictional Colorado desert town in the 80s. The story follows 15-year-old June Lusparian, a Mexican-Armenian teen struggling to make sense of everything—her life, her sexuality, and her future. Touching on numerous settings and themes ranging from the LGBTQ community to the punk rock scene to the Reagan Era and high school shootings, the book features elements of the prose novel, screenplay, and graphic novel illustrations. It’s a story about finding hope and the transformational power of creativity in overcoming adversity. It’s about the power of love rather than the love of power. And a punk rock girl who falls in love with the cheerleader, who loves her back.

Gretchen: With all the options out there for telling stories, how did you decide on a graphic novel?

Ji: Well, it’s a hybrid novel, not a pure graphic novel. And the reason it came about is because even though I’m pretty well read, I’ve always hated reading. It’s really more of a mechanical problem than it is a content problem. I’ve always had a problem with staring at 100 to 300 thousand words. That never made sense to me, and I can totally relate to why a lot of people don’t like to read. People say our generation or the new generation hates reading, and they look down on us. But people didn’t figure out until social media got big that it has nothing to do with the fact that we hate reading; it’s just that our minds work differently. Our minds are much more fluid and visual and we need different things out of reading that books can’t always give to us.

The reason I created a hybrid is because I’ve always wanted to read a book the way I would like to read it. When I sat down and wanted to write this novel, I almost quit because I couldn’t write the way you’re ‘supposed to.’ So I said, fuck it, I’m just going to work with a really good editor who is also my friend, Michael Mann. He’s absolutely brilliant; he’s an author who’s taught creative writing and graduate studies in feminism and rhetoric. Michael helped me break rules in a way that’s not so experimental that it would be problematic for my first novel.

I thought about all the different mediums of writing that I love—I write screenplays, too—and I took stuff from screenplays, from prose novels, and from graphic novels. And I noticed that with every one of those mediums, there’s something about each one of them that I consider to be completely useless. I only took from them what I liked and everything else that didn’t work, I threw away. So that’s how my hybrid came about. It’s completely my own invention.

It’s all about efficiency for me. I don’t know if it’s because of my film background, but one of the things my directing teacher said to me was, “Get it up, get it in, and get it out.” I don’t know if that was meant to be pornographic, but it was intended for the economy of filmmaking. You get in there, you get your shot, and you move on because you have budget involved. That probably isn’t the best way to describe it because the efficiency isn’t about rushing the process, it’s just about ‘why do I have to suffer through this particular process of reading when there are other ways of doing things?’

G: Speaking of your process, how did you decide on which elements you wanted included in the story? Are there certain aspects you only did visually or only in prose, for example?

J: That part was actually very easy for me. It was intuitive, a lot of common sense. When I read novels, there are things about them that I really love, like that slow creative process of loving words, going deeply into that dream space where you can marinate and take your time. But there are things that are kind of masturbatory. Do I really need that much detail? Is it for you, the author, or is it for me, the reader? And that’s when the efficiency part kicks in for me.

There are other aspects of the rules of novel writing that weren’t really efficient. I don’t really want to figure out where we are in the story, location-wise. As a writer, I also don’t want to deal with describing to you how I left the room and ended up in a restaurant. It’s hard for me to do, and it really doesn’t matter. So, I took away the whole problem of interiors, exteriors, and location and just used a cyber-texting way of doing it efficiently, which is using the @ symbol and #. You know, like, “@Paradise High School #Cafeteria.” Right away you’re there.

That is actually borrowed from screenplays, but I didn’t want to write a screenplay so I created my own way of shifting locations.

The graphic novel part is very interesting to me. I love graphic novels, but I think I can only handle one page. It’s kind of visual overload. Just as a book can give you an overload of hundreds of thousands of words, the magic of looking at a picture kind of gets lost when the whole thing is images. I’m sure people who love comics would disagree, but I don’t read comics. I can’t read a page filled with images and thousands of word bubbles.

What I love about graphic novels is the imagery and ability to immerse yourself in an image that words fall short of. It was only after I sat down and drafted out the scenes that I looked at the images and realized that they are more like portals than they are explaining the story. You’re reading the novel, but then you take kind of an Alice in Wonderland-type excursion into an image, and it puts you deeper into the world I’m talking about. So, they’re used sparingly in places I thought were needed instead of doing a full-on graphic novel.

Those are some examples of the techniques I invented and used. Oh, I also want to mention one other thing about novels that I find utterly useless, which is that I don’t really see the point of “he said, she said, she replied, he explained.” I don’t see any purpose for that! That’s where screenwriting is brilliant, because you just have the name of the character and they talk. What’s beautiful about it is that you don’t have to know that the character is screaming. When an actor reads a screenplay, they imagine how a character would speak based on the words they say.

The whole experience altogether opens up your imagination and allows the reader to do more of the imagining, kind of like an actor would do when they read a screenplay. They’re doing more imagining and filling in the blanks rather than me having to say exactly what a character looks like when they talk. So when I do describe how someone looks, it’s because I really need you to know it!

That’s the kind of efficiency I’m talking about.

G: You’re giving your reader more agency to participate in the creative storytelling because they’re supplying their own interpretation of how things are said.

J: Exactly!

G: That’s really cool, I like that a lot. Speaking of what to include, the graphic novel is set in the 80s. Was that purely an aesthetic choice or is there some other significance to it?

J: I’m curious why you asked me that question, and I really love that you asked it. So, I’m going to answer assuming I know why you asked it.

There is nothing more irritable to me than when I see a new book, movie, art exhibition, or anything coming out that is 1980s just to be hipster cool or trending. It seems like when you look back in history, people love doing things that are set 20 or 30 years previously because it’s ‘cooler.’ At times, it just seems to be a fashion statement. I don’t know why that is, but you can always tell when someone is telling a true story about a particular era or if they’re just trying to be cool. I just want to say, I’m not a hipster and I’m not hipster cool! I’m just real, or I like to think I am.

Red as Blue is born purely out of the 80s. It’s really important that I talk about the 80s because anything before the internet was the dark ages. Unless you were part of the ideal at the time—blonde, big boobs, drove a Mustang, ran with kind of a Barbie and Ken crowd—unless you had a Brady Bunch family and all those Americana-type things, you were invisible. You were excluded. You weren’t part of the American narrative. You were not considered American and because of that, it permitted a lot of hatred and prejudice.

That was the 1980s for me; it was completely dark. This story comes out of that darkness, and I think because it was so dark, it also brings a lot of the beauty with it. The strange beautiful light that came with the alternative music scene and the post-punk movement that completely shaped society up to today.

The 80s were so critical because we were fighting for our lives. Listening to music was war, because if you didn’t like Bon Jovi or Bryan Adams, you got shit for it. If you listened to Depeche Mode? You’re a fag. I’m sorry, but that’s the way it was. Music was war. The stuff that we were listening to that was alternative was a form of—we didn’t know it at the time because we didn’t think about it—but it really was pure activism. Not political, but we were living it. We were walking targets.

So, the way my book captures the 80s is more like a redemption of the 80s that never were for a lot of people.

G: Shifting the topic a little bit, what inspired you to start writing?

J: Survival. I’m Vietnamese and was born in Laos, so we didn’t come here by choice. We came here as refugees, running away from a violent war and being displaced. We came to this ‘America the beautiful shithole’ because it was the promised land, the dream, the place that refugees go to do be safe and welcomed. But it wasn’t that way at all. My whole life was filled with “Go back to where you come from” or “What are you eating, dog?” Every name that you can think of, I was called every single day. I was completely torn down and ripped apart every single day by the environment and even by the other people who were oppressed, the Mexicans. They were treated like second-class citizens in Colorado where I grew up.

Then, moving to the suburbs, I got the same thing from the white, Christian culture except they were more awful with it. They didn’t say it to your face, they said it behind your back. I said, “I can’t handle this.” If I’m going to have racism, I’d rather have someone punch me in the face than say something behind my back because that’s just a slow, gnawing cancer. It’s just so painful.

I started writing for survival. I didn’t write because I was a writer, I couldn’t even spell. I was almost completely illiterate to be honest. All the kids around me were speaking slang. That’s why the character in my novel says ‘ax’ [instead of ‘ask’]. It’s not because I was trying to make my character weird, it’s because that’s how we were talking. We really were ‘axing’ people stuff.

I started writing through journaling, and it was something that I did instinctively for survival. I didn’t realize it was saving my life. The type of journaling I did wasn’t diary writing: “Dear Diary, today I bought some spandex at the mall.” It’s not that. It was going so deep into yourself and healing yourself and having someone to talk to because there was no one else who could understand you because they weren’t having your experience. I wrote so much that I was filling up Mead notebooks; whether they were 80 or 120 pages, I’d fill them up both sides. I was furiously, furiously writing.

I continued writing, and it evolved into poetry, then it evolved into essays, then it evolved into creative writing. It carried me through everything I did, including filmmaking. Because a good story has to come from writing, it doesn’t come from actual filmmaking.

So, it’s really interesting because writing has always been with me even though since childhood, I’ve pretty much been a visual artist. It’s interesting that I’ve kind of ignored writing but it was actually always there, and it took me this long to realize that I’m not a bad writer.

G: Given your personal experiences, talk to me about the importance of representation of marginalized communities. How did that shape the story you tell in Red as Blue?

J: The first thing is, I grew up in the housing projects of Colorado. It’s really upsetting to me that for the longest time, even up to today when I tell people that I grew up in the ghetto, people laugh. They think that Colorado is Aspen, Telluride, and film festivals. And that’s exactly the problem. There aren’t enough stories talking about your environment, and if you don’t talk about your environment or don’t tell your story, you’re invisible.

To describe this environment that June lives in would disturb a lot of people who haven’t heard about the place that she lives in. They might think I’m making all this up. But for those who have grown up in these Chicago-kind of neighborhoods or Mexicans struggling to be American but not—and I was strangely a part of that environment—it’s real. People tend to think it of it as fiction. But, when you tell the stories of these kind of communities, it brings people together and it educates others. They realize, for example, that Colorado, at least the Colorado I grew up in, isn’t just skiing and sunshine.

G: What do you want to see more of when it comes to depicting queer and non-white characters?

J: I’m not sure how to answer that question, because when I’m writing about LGBT characters, I’m not thinking about race. I’m usually thinking about what makes a character different. I think the core of a lot of the problems we have in this world, and especially in America, in terms of accepting one another is the differences, regardless of what race or gender we are. For me, I’m interested in characters who have some form of ‘otherness.’ I guess in political terms the word is intersectionality, but I don’t even know how to spell that word, much less how to use it!

But I like otherness. And in terms of otherness, it doesn’t even matter what—if we’re black or white or gay or straight. When we see that otherness in a person and we connect to them, it opens up our consciousness and our hearts. And that’s the part in us that destroys stereotypes. When you meet someone and experience their otherness, you see them as a human being. Like when you read stories about a Mexican in a white world or a lesbian in a straight world, or even worse in a straight male-dominated world, you start to learn what it’s like to be that person. When you experience a person’s otherness, you relate to them no matter how different they appear on the outside. That otherness is more important than anything else for me when it comes to writing characters.

I love that my main character is Armenian-Mexican, but her otherness is that she’s also gay. And her real otherness, her true otherness, is that she’s real, innocent, and incorruptible. And the girl that she falls for, and that falls for her, is a white cheerleader. But her otherness is this beautiful capacity to see through skin, class, and gender; she’s a beautiful girl because of her otherness.

So, more important than creating non-white, LGBT characters is if you can do it and still show this otherness. That really is what I’m going for when I write characters.

G: Is there anything out there—in film, television, or print media—who, for you, is getting it right in one way or another?

J: No.

G: Blunt answer, I like it! In what way?

J: Well, I have only myself to blame because I’m one of those artists that other people hate. I find artists, whether they be a filmmaker or a writer or a visual artist, hate this about me more than non-artists. I don’t keep up with what other people are doing, and I never have. They get really angry with me if I don’t know who a particular author is or filmmaker or painter.

I don’t keep up with what’s going on in the world because I am one of those artists who gets everything from within. I really do. I’m not saying that to be special. I don’t see any reason to look at tons and tons of stuff and then emulate or imitate it. Everything that I do is coming largely out of my imagination and experiences. Anything I truly need to know about makes its way to me because it’s meant to be and is often a synchronicity.

So, I really am to blame for not knowing what’s good out there. That’s why I answered ‘no.’

G: So, it’s really more ‘I don’t know,’ rather than just ‘no.’

J: Yes! More like I don’t know. But I have to say that we live in a super diverse world, and there’s no one size that fits all. There’s not one lesbian film that fits all lesbians. I made a film, and a lot of lesbians probably can’t relate to it, because my films tend to be art films, more European style. They’re not the stuff you see on TV or mainstream filmmaking.

The only way you can get it right is to get it right in your niche market. And if that niche market catches fire, then it becomes accessible to the mainstream and to more people, which is great.

I don’t want to spend time naming names or bagging other people’s work, but one thing no one is getting right in terms of lesbian films is that I’m offended when men make lesbian films or even dare to write a lesbian story. That is so offensive to me, and they should be ashamed. People can have a lot of arguments around it, and it’s true, an author, director or anyone talented can make anything brilliant. But I haven’t examined this enough to be able to describe how sick it makes me feel. It’s just so offensive.

G: Red as Blue touches on the very sensitive topic of school shootings, which seems more relevant now than ever. What led you in that direction and why do you think it’s important to tell this story in media for teens and young adults?

J: First, I want to say that I thought it was really eerie that the Florida MSD shooting happened right when I started promoting the book. That was strange because for the longest time, I wanted to talk about homicidal teens and high school shootings somehow, in some way, in storytelling.

At the time that I was developing the story, nobody understood why the hell I was writing a teen love story with this stuff in it. I just felt like it needed to be told, but it needed to be told not as a focus. When people write or create stories about Columbine or high school shootings it’s always focused on the violence and on the mind of the killer. I’ve always felt that this isn’t the right way to go about it. The only way that we can heal society in terms of waking them up to why these things are happening is to open up their hearts. And that’s why it has to happen in love story.

The message I want to get across with the school shooting happens in the background of the society that my character June lives in. Ever since Columbine happened, I’ve been disturbed by high school shootings, and I sprinkled it in the story’s background in a way to show the societal cancer behind that shooting. When you look at the story and you see all the bullying, violence, hatred, and all these kids acting kind of Lord of the Flies in a 1980s way, and with the heavy white male patriarchal Christian consciousness going on in the time—all of that is the cancer going on underneath. That’s what is causing these kids to go berserk. I didn’t make it so I’m hitting you over the head with that message, but that’s really what I’m trying to show. To show the youth that they’re not the problem, society is the fucking problem.

And that’s what’s happening today. The youth are standing up because they didn’t have a voice back then. They were supposed to be obedient, listen to authority, and do what adults say. They didn’t have the media outlet to say anything and they were so used to being pacified, to shutting up and letting adults tell them about their experiences. So the cancer continued to grow. I was so pissed when I saw these so-called experts talk about the youth experience on the news. I was like, “Fuck you. You don’t know what the hell you’re talking about. You’re the ones who caused these problems.”

Even back in the late 90s, if you dared to say that, you’d get shit for it. Nobody wanted to believe that religion was behind it or that society was fucked up. You couldn’t question authority. What’s happening now is that the cancer has grown so huge that it can’t be ignored anymore. Gun control is not the problem; gun control is just a massive, most obvious tumor. The kids—thank god for the kids. Social media has enabled them to take over and to show the adults that they didn’t know how to raise them. Basically, the kids have been raising the adults since Columbine because no one did shit for them.

That’s what I’m going for in this novel, and I’m so happy that in some strange way whatever is happening right is so true to what I dreamed of when I was writing this. The youth is so inspirational.

G: What do you hope teens reading your story walk away with?

J: How can I answer that without being kind of cheesy?

G: Be cheesy all you want!

J: I think I’ll stick with something simple and important to me since the time I made my short film “Nune.” It’s an adaptation and millennial version of Red as Blue in compacted form and takes place in modern times.

What I was going for there is the same thing I’m going for here with the book, which is that I want to show teens that no matter how dark, or how hard things are, or how invisible you feel, it is always worth holding onto your highest ideal. You need your highest ideal to save you and pull you through. In this story, the highest ideal was love for one another. And aside from that, for June, her highest ideal is to make music. For Beverly, her highest ideal is being good at what she does, which is sports.

But you have to have ideals. And if you don’t have them, you have to create them, because you have to hold onto something. That’s your life raft. That’s the part that gets you through, especially when the world gets fucked up and you have all these adults who don’t understand you and try to derail you and tell you you’re wrong about things when you know you’re right. You know you’re right when you’re holding onto that ideal.

G: What’s coming up next for you? Any other projects you’re working on that you’re excited about?

J: I’m just focused on promoting the book. I think I need to take a vacation and clear my mind to work on my next project, which will likely be a novel. More than likely it will be something transcendental, and probably female-centric and more than likely LGBT.

G: Thanks again for taking the time to talk with me; I’m so excited for the release of Red as Blue!

J: Thanks for interviewing me, it’s been really cool!

—

Red as Blue comes out May 15th and will be sold at all major online retailers in both ebook and print. Preorder begins March 27th, which is just around the corner, so get ready to reserve your copy! You can also ask your local library or bookstore to order a copy.

Follow on Facebook: @redasblue or visit http://www.redasblue.com. Also, check out Ji Strangeway’s promo video: