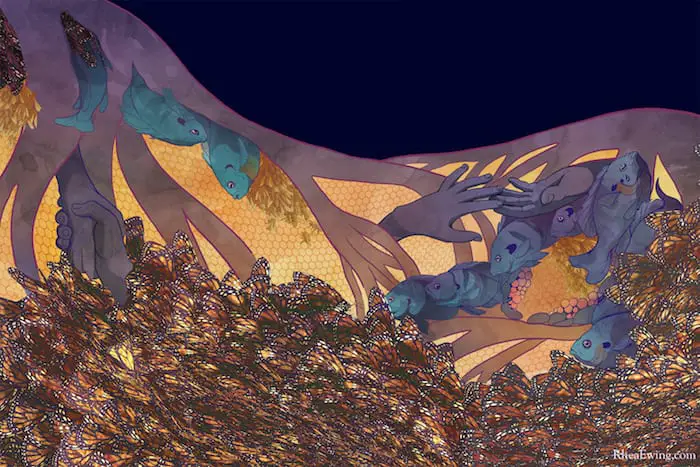

Most of my interviews for Creator Corner have highlighted authors, which makes sense given my love of books. But when I was at WisCon in May, I went to the Artist Alley and fell instantly in love. With a painting called “Justified Bodies”:

When a friend of mine mentioned I might want to interview Rhea Ewing for this series, I was delighted to discover that they were the artist behind painting I had fallen in love with. I was even more delighted when we actually met to talk about their art, being an independent content creator, and their upcoming project Fine: a comic about gender, a graphic novel about, well, gender. We talked for almost 45 minutes, but trust me, you’ll want to hear everything they have to say.

Gretchen: How long have you been pursuing your art and what got you into the visual arts in the first place?

Rhea: This is a little embarrassing, but I first started trying to get better at drawing when I was in fourth or fifth grade because I wanted to be the coolest kid in class, and I could draw wolves better than anybody. So I was that kid. Then I realized, “drawing is pretty fun, let’s keep doing it.”

Over time, I got to this point in my art where I had a lot of passion for what you could do with all different kinds of art and storytelling. And that you could make connections between all of these different ideas and people’s real, lived experiences day to day. I wanted to be able to play with those connections and I still relish in that challenge.

So, in my freshman year of college, I decided to change my major and pursue art full time. Up until that time I had been interested in pursuing a degree in the sciences—explains a lot of my interests in my art, right?

G: With all the options out there for telling stories, especially personal stories like interviews, what made you settle on a graphic novel format for Fine: a comic about gender?

R: The first graphic novel that I read that made me think comics could do some cool stuff was Blankets by Craig Thompson. I was in high school when I read it and realized you could talk about all these complex, internal things and you can make them external and present them in a format other people can understand. Shortly after that I read Persopolis by Marjane Strapati and that was another big influence on my work. Persepolis and works like it made it clear to me how comics could make someone else’s world understandable and relatable to the reader. I have also always liked that with comics you can talk about complex ideas in a relatively concise format. You have the images to support the words and vice versa.

So, I wanted to do a comic to talk about a thing that seems complicated and weird and that I don’t understand, so let’s go with gender. I don’t really know what the hell that is, let’s do it! When I first started the project, I was a senior at UW Madison and figured it was a project I could do over the summer.

G: *snorts with laughter*

R: Yeah, right? I was naïve. I thought I’d interview maybe a dozen or two dozen people, make a little zine about what gender is. When I started doing that, I encountered all of these blocks. There were a lot of things I encountered that were very intriguing. Like, I was talking with transgender folks, cisgender folks, and people who don’t identify with either of those labels; there was a lot that people were giving me that was really fascinating and went beyond comments like “I’m transgender” or “gender is something that I think about a lot.” There were a lot of interesting things people said about how they think about their gender, or ways they would get struggle a little bit with what people expected based on the gender they identified as that didn’t work for them. Again, this was both cisgender and transgender folks saying things like this.

I wanted to talk about the complexities of gender more and I realized there were a lot of perspectives I was missing. The blocks that I mentioned were in getting to those perspectives. There are a lot of, if you want to frame it generously , a lot of unintentional divides in the trans community between transmasculine and transfeminine folks or between white folks and people of color. So as someone who was assigned female at birth, very white, and living in Madison—a city with a lot of unresolved racial disparities and problems—plus, at the time I didn’t have the language to describe myself. That’s part of why I was interested in this whole project. So, I was just like, “what is gender, even?”

But if you’re a trans woman and/or a trans person of color, you see this white, assigned female at birth person coming to you saying “what is gender, even?” that’s really scary! And that’s scary because in the past there have been people approaching those questions apparently in good faith who have used them to do a lot of harm to the trans community, to the most vulnerable among us.

I kept encountering these blocks, so I realized that in order to do justice to this topic, I needed to have a better sense of the demographics of the people I was talking to. I also needed to work a lot harder to reach some of those voices. That’s how you turn a summer-long project into a seven year adventure and a little zine into a graphic novel!

G: What surprised you most in the process of creating Fine: a comic about gender? Has working on it changed your own perspective on gender and if so, how?

R: Oh yeah. There’s a lot that has surprised me. Right from the get go encountering all of the blocks and divisions, or people using terms I didn’t know. Up until that point, I had been that person who considered themselves an ‘LGBTQ ally.’ I grew up in a small town in Kentucky and ‘for some reason’ I was really protective of and wanted to hang out with the queer kids, I didn’t know why! I cared about them really intensely.

And one of the things I had encountered was that sometimes you dip your toe into online spaces or you go into a group where people have a very encoded and advanced language they’re using to talk about all these nuances. I didn’t have any idea, and I felt like I needed to have everything about myself figured out before I could go into those spaces. “This is exactly who I am, here’s my list of labels, let me hang out with you.” On top of that, just being kind of a shy, introverted person, too. That uncertainty of exactly how to define things combined with, like, this fear of rejection. Feeling weird about straight cis people is one thing, but if you go to this space that’s supposed to be safe for you and get the feeling that you’re not ‘gay enough’ or ‘trans enough’—I had a lot of anxiety about that.

That’s where I was coming from going into this. Then, I encounter all these blocks and it’s more complicated than I thought even from my perspective. And the more I talked to folks all over the Midwest, I realized that there wasn’t this single, unified language people were using to talk about gender. It varied a lot by region. There were some communities where butch and femme were really common ways to talk about an aspect of someone’s experience with gender. There were other places where the response to that language was “that doesn’t make sense” or even “why would you even say that?” So it wasn’t just that I was this person who couldn’t figure out how to describe myself, these are words and languages that are shifting and really contextual depending upon how old you are, where you are, race, all sorts of things.

G: There’s cultural upbringing, too; if you’re an immigrant or come from a family of recent immigrants, country of origin, all those cultural and religious layers as well.

R: Right. I’m glad you brought that up because I interviewed a couple of folks who identify as two-spirit, and for them, the cultural aspect of who they were was inseparable from their gender identity.

G: That makes a lot of sense.

R: I learned a lot. A few years into it, I hit a point where I couldn’t even care anymore if someone thought I was using the wrong words for myself because I realized that maybe someone always would. That’s the nature of how diverse our communities are. So, I came out as bisexual and genderqueer? Nonbinary? Agender? I still don’t really have a word that I feel like, “this is the word!” but I have a constellation of words that I can say, “it’s somewhere in that direction.”

It’s also taken me from a point of, “I don’t understand gender and I don’t relate to it at all, why do we even need it,” to “okay, I don’t know what’s going on with my gender, but I clearly have some kind of feeling about it and other people clearly have a firm gender identity and relate to this system in a certain way.” My genders just kind of like dark matter. I can’t see it or detect it through the general background noise of the universe, but the effect that it has on me still affects me a lot. Sometimes I feel like I don’t have a gender but that means that I’m thinking about it constantly and have built my career around it.

G: I love that metaphor of dark matter; I haven’t heard it before.

R: Yeah, I’m working with the Arts + Physics project right now that pairs artists, writers, and physicists together with high school students and you all complete a project together by the end of it. Anyway, I have the pleasure of working with physicist Dr. Kim Paladino . Kim studies dark matter so I’ve been thinking about it a lot. Hmmm, there’s a thing that has immense effects that we can’t figure out, you say?

G: We know it’s there, but we don’t really know how to define it, hmmmm.

R: We study it indirectly and then we figure out more and more…Did that answer your question?

G: Yes, absolutely. Moving on, what do you hope that audiences reading Fine: a comic about gender work walk away with?

R: Okay, so. A really common question for creative folks is “who is your audience?” I try to picture several different audience members in my mind when I’m working on the book. One is the queer kid who has or hasn’t figured themselves out yet in rural America, because I was that kid. When I was in high school, I read books, comics, and things like that about queer experiences. I read a lot of the webcomic Liliane Bi-Dyke, and there were times when my parents were reading over my shoulder and asked if I was queer, from a place of wanting to be really supportive. I told them, ‘nah, I don’t know.’ Basically, when I eventually came out, no one was surprised.

Anyway, I think of that experience, of not even having the language to start conceptualizing this and having a community that isn’t large enough or safe enough to talk with people. People who need a way to explore those things—for those people, Fine is an invitation: “It’s okay to look into this stuff, to talk about it. And if you feel weird about it, you’re definitely not alone.”

Then, I think about folks who are in a more similar space to where I am now. Maybe they’ve put some thought into gender. I see this temptation to distill it into a catchy phrase like “gender is between your ears” or to use diagrams with different spectrums of experience. I think that’s so temping for people because you want to be able to explain things concisely. In fact, when I first started the project, I wanted to make a model like that, too. Then, I realized through talking to so many different people that I couldn’t do that. There were so many different experiences and ways to talk about it.

Ideally, for folks who are at this level I want them to see that this is complicated and that’s beautiful. I’m not going to tell someone they’re describing their gender wrong; rather, they’re using a different language than I am. I want the work—it’ll be a big book, it’s looking like 375 pages at this point—to be take that as a whole and a representation of what happens when you try to talk about gender without first establishing shared language. Can you do that? What are the results of that? I want people to ponder on that.

Because another thing is that a lot of my interviewees often used the same words and phrases in contradictory ways. I ask most of the people I interviewed the same sets of questions like, “what is the difference between sex and gender?” Some people say there isn’t one, other people say, “it’s this,” and other people say “weeeeeell, I don’t know.” It’s complicated” Someone could interpret ‘sex’ to mean ‘genitals’ while others interpret it as ‘chromosomes’ while others interpret it as ‘sexual orientation,’ for example.

I want to show that you can have these conversations. You can be open and ask questions about what people mean. For me, that’s a much healthier space to explore ideas in rather than, “oh my gosh, you described yourself as transsexual, how dare you!” But that’s a word some people identify with and has historical weight. Why do we always flip the language around like that? There’s an essay by Julia Serano about the carousal of language around transgender experience that talks about how a term will be accepted for a while and then be seen as a slur. We don’t see that in queer identity labels that are under less scrutiny. ‘Gay’ and ‘lesbian’ for example have specific origins and if you look at the origins, they don’t really capture that entire identity but words can evolve and change.

G: People are more comfortable with the lack of precision with more widely accepted labels than they are in what they would consider new ones.

R: Exactly. Whereas with identities that are under more scrutiny like being bisexual, gender nonconforming, or transgender, there’s more of a cycle of distancing from words associated with being more marginalized or having violence enacted against them.

G: That’s so fascinating, but we have to move on. You talk on your website about being inspired a lot by nature. Tell us a bit more about how you see nature as a mirror of and challenge to human experiences.

R: So, nature is pretty awesome. There’s a reason why at one point I wanted to devote my life to studying it through science, and I still do, but as a ‘fan scientist,’ the one who can explore a lot of topics.

What I love about nature, much like with things like gender, is that the closer you look at it, the more complicated, lush, diverse, and vibrant it becomes. Take the idea of survival of the fittest for example. For a lot of people, that immediately conjures a certain image of a big touch strong animal versus a feeble animal that can’t get the food in time. But when you actually start looking beyond that stereotype level, you see there are a lot more complexities of social interactions, communication between individuals within species, and also a lot more diversity.

One of the species that I featured in my Seven Strengths series is the bluegill sunfish (they’re actually in the lakes here). They’re a fish species with four genders. Roughgarden’s book Evotion’s Rainbow does a wonderful job talking about how the cultural biases of biologists studying nature in the field can have a severe impact on what they perceive. Roughgarden defines gender as a distinct appearance associated with a set of behaviors. So, the bluegill sunfish has four genders. There’s the big orange males who make a big nest at the bottom of the lake and they guard the nest fiercely, looking for a female to lay their eggs in it by proving they can protect the eggs. They can be really territorial and aggressive. Sometimes they’re so aggressive they’ll attack females who visit them, which makes the females wary. They don’t know if the males are dangerous to approach.

Another type of male is the ‘sneaker male’ who hang out around the edges. They have a different appearance and body structure. They’re whole game is that when a female visits the nest of an orange male, they sneak in, do their thing, and run away before the orange males can catch them. It’s really common in lots of species to have different types of males, and sometimes they switch which role they’re in during their lifetime.

What excited me was the third type of male, which for a long time was classified as a ‘female mimic,’ that he was tricking the orange males. But, the behavior and appearance of these types of males is different enough from the females that Roughgarden proposes that’s the wrong classification for them. These males school with the females for most of the year, then, during mating season, they will court one of the orange males. If the orange male accepts his courtship, they’ll form a partnership with a nest together throughout the breeding season and then they both mate with any females who come to visit. The females don’t stay to take care of the eggs, so the fact that male stays around makes him different. And from the female’s perspective, the fact that the big, tough orange male is chill enough that he has a partner means he’s safer.

It’s also cool because when there’s a partnership like that and a female comes to visit, they all mate together. The smaller male will be in the middle and help coordinate the mating process like, “I like you, I like you, here we go.”

So, nature is a lot more complicated than we think and sometimes cultural biases—for example against trans people or a certain vision of gender roles, things like that—can affect our ability to observe the natural world accurately.

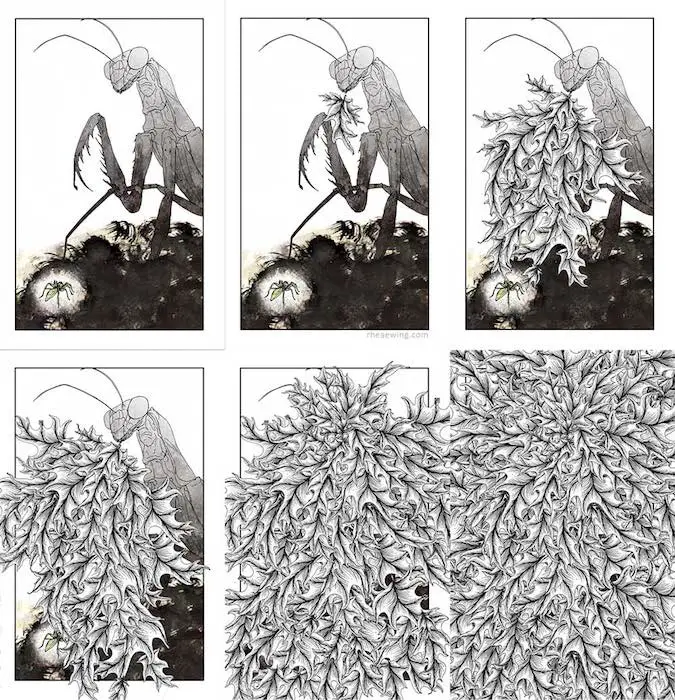

It can also work in other ways. There’s a series that I’ve done called the Ancestor series about human evolutionary ancestors and relatives. The thing about paleoanthropology is that when we find fossils and artifacts, the way someone interprets them often ties into what that person believes it means to be human: What do we value? What should we value? How important is it that we be clearly distinguishable from our evolutionary ancestors?

There are also some really scary racists and eugenicists who draw parallels between contemporary modern humans and certain evolutionary species. What’s fascinating is depending on whose DNA they think has what they will completely change whether those parallels are good things or bad things. Anyway, the Ancestor series is all these figures cloaked in leaves and artifacts holding these fossil skulls up as masks. Because we have all these ideas on our own of what we want things to mean; those ideas, hopes, and hang-ups are like using these fossil finds as masks like, “oh look, see, I’m legit.”

G: It goes back to what you were saying at the beginning about visual art being a concise medium, because it took you longer to explain that to me than if I had just looked at the art and absorbed that message.

R: I almost always want to have an artist statement next to my art pieces. On my website I have these long artist statements, and if I do a gallery show I’ll bring them along to hang next to each piece. I want my pieces to work if people don’t have all that background information, but there are pieces where you might not know certain things unless I told you. There’s a species of butterfly that I feature in one of my Ancestor pieces called the large blue arion. As caterpillars, they go and sing to an ant colony and release these pheromones to which the ants reply, “Woah, this is the biggest ant child we’ve ever seen.” The ants then take it into their nest and take care of it. Then the big ant child that is actually a caterpillar eats and pupates. When it emerges, it’s clearly not an ant baby, so it sings a different song and the ants clear the way for it to walk out.

What’s interesting is that the usual MO is that these ants attack anything that’s not a part of their colony on sight. Ants are kind of the worst. There was an ant scientist talking about two ant colonies, same species, with this line in between them stacked high with dead ants. So that’s a tension I like playing in my work, too. I have this drive to see all of these beautiful things in nature, but that’s another bias, right?

Anyway, there are all these surprising connections like that that I think are interesting and I want to showcase those, but it gets tiring to verbally explain to everyone who walks by. I have those artist statements to help.

G: Are there any other themes or sources of inspiration you incorporate into this network of connections in your art?

R: Two things immediately come to mind. One is that I really like big things that are made up of lots of little things. A big influence of that in my work is the Korean three dimensional and installation artist Do Ho Suh. A lot of his work is lots of figures or, like, a piece of armor made out of army dogtags that were flowing out onto the floor almost like feathers or scales. He did a piece where instead of a pedestal with a statue on top, it was a bunch of smaller statues supporting a pedestal.

That’s a big interest in my work. I do a lot of things where I make these amalgam, almost spirit characters made out of leaves or insects. A part of that is I want to fit all these ideas and interests that I have into one thing.

Another thing that often comes up in my work that people comment on is that I draw a lot of hands. Hands forever remain my most and least favorite thing to draw. They’re very complicated, but they’re also very posable and expressive. The difference between someone gripping a water glass very casually versus white knuckling it a bit can tell you a lot about what that person might be doing or feeling. I use hands in my work to express that there’s a human element, idea, or emotion. But I like doing it through hands because when you draw a face, people get stuck on the question of who the person is, their age, place of origin, how they’re supposed to relate to them, etc. Hands are a more generalized statement of humanity.

Part of what I enjoy about my comics is that it’s the opposite. I’m able to depict a character who represents a real person and I want the audience to be able to relate to them while also seeing all of the things that are unique about them. My comic isn’t a general statement about ‘this is what humanity is like’ because that doesn’t work for all the reasons I mentioned earlier about that project.

G: Most people tend to think of queer representation in literal terms—queer characters in narratives, for example—how would you describe your art as a representation of queer identity and experience outside of that very literal conceptualization of it?

R: I’m really excited that you asked me this question. For me and for my identity and the way I experience and think about my gender and sexual orientation, queer is an acceptance of complexity and of other and of something being strange or of doing things in a different way. There’s a really wonderful comic called Queer: A Graphic History, and one of the things it cites is Dory from Finding Nemo and how, because of her memory, she doesn’t experience events in the same time and space that everyone else does. But she’s still able to have all kinds of meaningful connections with other fish. That kind of mindset is what I’m thinking about.

My perspective on nature is that it’s complicated. There’s a lot of different survival strategies and we have a lot of baggage, things we want to be true and our own agendas when we look at it. If your impression of survival of the fittest is ‘winner takes all,’ what does that imply for your politics? All those things are important. Taking a queer lens on them means making room for the abnormal.

G: What are the biggest challenges you’ve faced being a queer artist? How can our readers best support original artists like you in pursuing your work?

R: A lot of the challenges I deal with as a queer artist involve wanting myself and my ideas to be understood at least marginally well. There’s a certain pressure for artists as small businesses to market themselves or put themselves out there in a certain way. I’m not always comfortable with that because I don’t want to be misunderstood.

I did an interview a couple years ago and when it came out, they had misgendered me in half of it. But not the other half, so it was kind of strange. I’ve had art curators take my bio and artist statement off of my website and when they change the first person to third person, they used all of the wrong pronouns for that but had kept the right pronouns elsewhere. There’s an extra layer of work for me to do.

I want people to focus on my work and appreciate it for what it is, but that means appreciating me for who I am. At least in a rough sketch kind of way regarding my pronouns and why they’re important to me. I’ve had to get comfortable sending people messages about my pronouns and using them consistently in professional contexts.

Another challenge would be the challenges artists everywhere face. Culturally, societally, we place a lot of value on creativity and the beauty or aesthetics of things, but we don’t place a lot of value on the people who make those things happen. There’s not a lot of funding for the arts. A friend of mine recently lost a gig because she made a bid and all of the other artists except her didn’t budget compensation for their own time into the proposal.

What that leads to is that the most privileged voices get heard the most. If art can only be done on a volunteer or mostly volunteer basis where you’re mostly working for minimum wage or below, then the artists who have the extra resources to support themselves or receive support from family members will be the ones you hear from the most.

A challenge for me is that I recognize I want work like my own to be out there more, especially Fine: a comic about gender, and I want it to be done by those who do not have the same privileges that I have. The fact that I’m able to bring this project to this point has cost 7 years of only being able to work part time, thousands of dollars in travel costs, hiring artists to help do inking and polishing steps. The fact that I was just barely able to pull all of this together is like, yippee for me, I guess. But if we want to see more of this, we need systems of support and structures in place that can support not just funding for the arts in terms of physical supplies but in terms of time and expertise. I actually applied for several grants when I was working on Fine and the consistent message I heard was, “We’re excited about this project, come talk to us when you’re ready to print it because we don’t want to pay for something to be made.”

But that’s more of a challenge with society and the arts in general. I’m very aware of the fact that I can live with my parents is a huge thing. But even the fact that we ask such things of artists means that there are a lot of folks we don’t hear from, and that needs to be fixed.

To combat that, if you’re in a position where you are working with an organization that supports the arts, help change mindsets. Like, “if we want to hear from a more diverse range of people, we need to be able to compensate people for their time, and we need to actively seek out diverse artists.” The people I want to hear from the most are the people with the least extra resources to give.

If you’re not working for an organization like that, it’s great to support artists directly through purchasing their work, making commissions, and platforms like Patreon.

Another way to support diverse artists would be to makesure that you’re holding everyone to the same standard. Something I see a lot of is that queer artists, artists of color, trans artists, other diverse artists in general are held to a much higher standard than cis white male artists and mainstream media. A big Hollywood blockbuster or a (white) male creative making a vague gesture towards feminism is applauded but something that’s supposed to be a queer or feminist work gets picked apart for every imperfection. We need to celebrate what a work does while recognizing what needs to be done next. The expectation that everything marginalized creators make needs to be perfect and save the world all by itself is toxic. We’re all consumers of media, so watch out for that in yourself Let go of some of those expectations of perfection.

G: As someone who wants to be a published author, I live with that same anxiety all the time.

R: Oh yeah, it has definitely defined my career.

G: Like, am I going to get picked apart for this? I’m trying really hard, and not in a “I’m trying hard, give me cookies” kind of way, in a “I really care about this, it deeply matters to me” way. I want to do the best job that I can, but are people going to recognize that or are they just going to assume that I don’t or didn’t care or just did it for cookies?

R: I have a lot of feelings about that, as that’s something that has been very detrimental to my mental health throughout my creative career. Even now I think about that. If I start experiencing a lot of harassment or get doxxed and my family is at risk, that could come from a few different places. I could see it coming from conservative spaces (maybe pretending to be liberal spaces), but I could see it coming from people on the left who take a very absolutist view of how these things work. It’s sick that I find myself in a position where I have to accept that a certain amount of this backlash is going to unfortunately happen from people that I would like to share community with. It’s hard.

And of course, I hold myself to a very high standard, which is why Fine has taken so long! But at some point I have to recognize that I can’t make a definitive document about what it means to have a gender identity in the midwest United States. I can’t even say this is what it meant within the time period in which I was doing interviews, which is between 2012 and 2016. I can’t even say that! This is just what the 57 people I talked to said about gender. It’s complicated.

The thing is, I don’t want to be immune to criticism, I just want those conversations to be productive. I want people to look at the gaps and missing pieces in my work and be inspired to create and fund projects that do what needs to be done next. When young creatives only see work being torn apart and creators being sent death threats, what are they supposed to think? I know it certainly held me back for a long time.

G: So, what’s coming up next for you? Any other projects you’re working on that you can tell us or hint to us about?

R: There are a few things I’m working on this summer that I’m excited about. I already mentioned the Arts + Physics project so you can look to see what the students who are involved with that come up with at the Arts + Literature lab later this year.

Otherwise, I’m working with Dr. Stephen Meyers, he’s a geology professor UW Madison. I’m working with him on a short scifi story summarizing key geological ideas and scientific mindsets for his students. It’s called “Grace in Space” and I’m super excited. It’s also kind of funny because this is maybe my dream gig and I’d given up on ever getting it, then I get this email out of the blue saying hey, here you go. I’m also doing a few projects with Dane Arts Mural Arts. The biggest thing I’d done with them before now is the mural on Broadway St. in Monona. So, I’m working on a couple of projects with them that I’m hoping will be near completion by the end of the year.

For Fine, the next step is just cranking out the pages. I did a lot of work editing and having it reviewed by people I trust early on because I knew that I wasn’t prepared to draw 375 pages of graphic novel only to realize I needed to rewrite half of it. So I’m in focused production phase right now. It’s hard because life expenses come up, health stuff related to family, or just things you want to do like have a family. Balancing the finances of that is hard, but I’m very lucky that I have very dedicated fans that have supported me for a long time.

If people are interested in knowing what’s happening with my comic work in particular, Patreon is a great way to keep up with it. Because I’m interested in Fine: a comic about gender being taken as a whole, I haven’t posted many work-in-progress images or things like that publicly. But, Patreon supporters get access to that. Plus, all my patrons are super nice and welcoming. It’s a wonderful community that keeps me afloat when things are hard.

G: Thank you so much for doing this!

R: You’re so welcome!

—

Visit Rhea’s website to see all of their art plus keep updating on what they’re working on. And if you’d like to support them and their work, especially Fine: a comic about gender, head on over to their Patreon.

—

As a quick, final note, I’ve been thinking of putting the past audio of my Creator Corner interviews up as a podcast (however crappy as it is at times since I was just using my phone) and starting to add more content with other creators. I would get permission from past and future interviewees of course. If you all would be into that, let me know! Some of these conversations go long because the creators are so damn interesting, and I’d love to give people access to it.