Entitlement is the fact of having a right to something. As consumers of stories made for commercial consumption—books, comics, movies, television, etcetera—we have an inherent right to an opinion about those stories. We have the right to like them or not, no matter our reasons. We have the right to take them or leave them. We have a right to analyze and critique content as it pertains to us, and its representation of us: our society, our community, our sexual identity and orientation. One could argue there is even a responsibility to analyze the content we consume.

But how far do those rights extend? And what are the creators, the humans behind the stories we consume, entitled to? Where do we meet halfway?

The relationship between creators and their audience has changed dramatically in the last fifteen years. While most audiences simply consume the content and leave it there, there is a group of more involved fans who invest time in analyzing it and generating content from it, from blog posts to think pieces to fanfiction or fanart. These fans also tend to seek interaction with the people involved with the stories. They tweet, they write open letters, they attend and create conventions. It’s a subculture.

Even if creators, actors, or executives would like to ignore fans—and even think they do—they can’t, not really. Fandom speaks. It speaks loudly. Fans now have a direct influence. We are no longer content to sit back and take whatever’s given. In a lot of ways, that is something to be celebrated.

This is especially true of television and comics because of their continuity. As I don’t consume comics, I have no input, so television will be the focus of this article, though other media might peek in here as well.

A Disclaimer

Before we go on I want to make sure you know this. I am not, by any means, generalizing negatively about the nature of fandom. I am a firm believer that fandom is largely positive, both for fans who seek community as well as for the creators who get constant feedback and become aware of how their stories are affecting their viewers.

Nevertheless, there are small, obviously toxic sections of fandom. The ones who start conflict between fans, for example. They bully fans and even actors and writers; they attack them personally beyond their opinions or work. However, I also believe these people are a minority. A minority whose voices sometimes seem to reverberate and poison the fun. Negativity, after all, tends to be louder than positivity.

But they’re not the ones I’m here to talk about. No, the kind of fan entitlement I want to talk about here is the subtler kind. Something I believe to be far more widely spread than the obviously toxic kind previously mentioned. This kind of entitlement is often presented as rationalizations that hide behind a true point or a real cause. The kind that walks the thin line between calling out bad writing and demanding that things happen the way they want.

Critical Consumption

The growing awareness that TV writers exist and can be interacted with has changed the perception of the media we consume. In my parents’ time, when people discussed a television series, they talked about it in terms of plot and characters, especially casual viewers like they were. Now, even most casual viewers are aware that there are people behind the screen who make decisions when they talk about television. If someone quits a show, they might say it’s because they didn’t like the writing, not because they didn’t like a character.

Social media allows us immediate, unprecedented access to the decision-makers. We can let these people know how good or bad we think their writing is, even as the show is airing. Common as it is now, this is taken for granted as nothing out of the ordinary. But it is nothing short of historic.

For the most part, the positive results from this outweigh the negative, in my opinion at least. Slowly but surely, we’ve begun to see a real change in the diversity of stories and characters represented on our screens At least some of that is due to creator-audience interactions. There is a long way to go, for sure, but fandom is far from backing down.

Criticism Is Inherent to Art

Art is not complete until it’s shared. I’m not sure who said that first, but it’s true.

We live in the era of peak television. There is a plethora of options for us to choose from, so the market is more segmented than ever. Genre, quality, and popularity varies, but even the smallest show has its fandom, even if it’s three people who live tweet from different corners of the Earth.

There are small niche shows that have incredible writing (The Expanse, you’re on my list), and there are big, popular shows that…not so much (ahem). With so much good TV to choose from, there is bound to be some bad mingled in between.

Once a story is out there, in a way some of its ownership passes to the audience, like in all art. It’s there for us to interpret and pick apart at our leisure. Audience interpretation is just as valid a lens as authorial intention. Stories can inspire fans to create incredible art based on it, or it can inspire angry rants several thousand words long about unfortunate implications in its narrative. The people who release it, especially the creatives, must be aware and accept that their work will be the object of scrutiny.

I repeat, their work.

They Are People Too Dot Com

This should go without saying, but writers and actors are real people with real feelings who deserve respect.

Even when the criticism of their work is warranted. Even when there is obvious carelessness. I daresay even when there is blatant offensive behavior coming from creatives, it does not give fans the right to resort to online hate. Death threats, personal attacks, and bullying are never justified. There is a huge difference between calling someone out and outright attacking them.

This is especially bad when fans claim to be defending a just cause. I’ll use Supergirl as an example. As you may know, many fans have been rooting for Kara and Lena Luthor (ship name Supercorp) to get together. This season, Lena was paired up with James Olsen (Mehcad Brooks) instead, which has led to people consistently leaving negative comments on Brooks’s Instagram account. It hardly needs saying that harassing Brooks’s account is unlikely to get decision-making people to bend to these fans’ will. Not to mention there are very unfortunate implications to a sudden wave of negativity directed at a black actor in “support” of a white LGBT+ ship.

There’s plenty of places you can rant about this plotline other than the actor’s personal account, who likely has no say in what his character does. Instead of support for a community, the message such behavior sends is “I feel entitled to get exactly what I want out of this show, and if I don’t so help me…”

What Do I Mean By “Fan Entitlement”?

As I mentioned before, fans really are entitled to many things when it comes to fiction. However, when we talk about entitlement in the context of fandom we often refer to the excess of it, or more accurately, the excessive perception of it.

Basically, fan entitlement happens when people feel they are owed everything by creators, be it the writers, producers, networks, you name it. These fans will loudly demand that creators bend the story to their preference. They take “give the fans what they want” to another level, often one that’s more personal. There tends to be a lot of self-victimization involved as well: “this storytelling decision is a personal attack on me,” which disregards the writer’s own obligation to serve the story, not the fans (though without being bigoted, of course).

Sometimes, fan entitlement is very blatant. It comes in angry rants and pestering on social media that can escalate into bullying. Often, it’s obvious someone’s having a big tantrum. Sometimes, though, fan entitlement is not so evident. The argument sounds solid, convincing. The one I find most concerning is when it hides behind something real, like I said. It is an “I don’t like this” buried in social justice, a subject which understandably dominates fandom discussion. Yet herein lies the titular thin line.

Let’s Talk About The Writers™

I have a bone to pick with the people who boast being knowledgeable about the TV business, but who also collapse the entire TV machine into just The Writers™. I see those words thrown around all willy-nilly too often. The Writers™ are apparently responsible for everything that happens ever. However, there are so many more pieces at play where television is concerned. More often than not, the will of the people actually hired to write scripts is at the bottom of the totem pole.

Javier Grillo-Marxuach is the credited writer of The 100’s infamous episode 7 of season 3, “Thirteen,” where Commander Lexa met her untimely end by stray bullet. If you take a look at IMDB, you’ll see that Jason Rothenberg (showrunner) is credited as developer. Then there are two credited executive story editors, two story editors, and an uncredited staff writer. So, who killed Lexa?

The answer is not as simple as The Writers™.

Good Writing/Bad Writing

Have you ever turned off your set after a disappointing hour of TV and thought, “I could have done that better”? Yeah, me too. Before I even turned it off I’d have already been thinking about how I would rewrite the episode to make it better. Even to make so much greater!

It’s very easy to criticize writing. From a distance the missed opportunities and plot holes are clear as day. When you’re the one writing, not so much. I used to be brutal with my criticism, until I actually had to write an industry level screenplay to graduate my Master’s degree. It was a rude awakening. Writing a script is hard. It’s not just structuring and plotting and keeping the theme on track and writing good dialogue, all of which is difficult. Most importantly, to write is often to lay your soul bare in some way.

I would say that warrants a bit of respect.

I’m not saying, “do not touch.” No one is exempt from criticism. Of course there are times when creators consistently ignore feedback and can thus lose fan respect. There is many a hack out there, some of whom are malicious (though not nearly so many as the internet seems to believe). What I am saying is the craft of writing itself deserves respect, so much so that it should warrant the benefit of the doubt when one undertakes criticism.

As I’ve seen it, fan entitlement often comes with a loss of that respect for the craft itself. There is no finer example than the “I care more” argument.

No One Cares But Me

There is something quite presumptuous in claiming to care more about a character and a world than the people who created it and/or nurse it every day. Not that this is not possible. One TV show can have many writers, and sometimes staff writers don’t like a character as much as others. It’s true that these stories matter to us in a different way. But as someone who writes, I can say I care for my characters very deeply. They are an extension of me, and I pour part of me into every single one of them.

What’s frankly annoying about this argument is that it often comes on the back of something bad happening to a character, regardless of whether it’s a good storytelling decision or not. A story development that fans don’t agree with simply because it doesn’t match their expectations. A recent example of this is the outrage about Luke Skywalker in The Last Jedi.

Longtime Star Wars fans especially had a lot to say about his storyline. To me, most of those arguments read as an unwillingness to accept that Luke may have changed in the last 30 years of his life. They saw him as infallible, immovable from the beloved image of the hopeful young man he was at the end of Return of the Jedi.

A lot of the dialogue revolved around how well the fans knew the saga. They knew Luke, and they knew what they wanted. So surely, they knew what ‘should’ have happened in order for them to like the story. Disney should have just given them what they wanted. Because you see, they knew best and cared the most.

But Do Fans Always Know Best?

No.

Guys, no. This should be obvious. Take a little trip down a “ship” or character tag on Tumblr, or worse, go into Reddit, and it should be pretty obvious why not.

Saying “fans always know what’s best” is the equivalent of saying “the client is always right.” We know that’s not always the case. Sometimes the client is being unreasonable. Sometimes the client is a petty child. Often the client doesn’t even know what they really want.

Check out some of the most common fan complaints, especially on Tumblr. They have to do with a fandom favorites’ perceived “attacks” from the narrative. “Can’t [insert literally any character] catch a break? The Writers™ have it out for them.” Some of these comments are meant in jest, but some are dead serious. If you let these fans get their way, there would only be movie nights and puppy parties happening. Nothing wrong with that, but that kind of storytelling is the generally reserved for the realm of fanfiction or romcoms, not dramatic television/film.

I should also mention that the screenwriting craft is something you learn, and it’s a hard job to get into. In most cases, it’s safe to assume the people in that position are there for good reason. Recalling that they care too, it should be noted that hurting characters often hurts them as well, but they have to put that aside to serve the story (and admittedly also to make money, though that usually means making at least a reasonably good story).

Emotions run high in fandom. We tend to be deeply connected with characters we relate to and it hurts to see them hurt. And yes, writers work to make us feel these things. Suggestions are valuable, but many should be analyzed on a case by case basis.

Entitlement and Personal Opinions

I want to drive this point home. Criticism of a show for reasons of racial whitewashing, lack of representation, toxic or unfair representation, etcetera, are valid and necessary. What is not valid is grabbing onto a true cause and using it to bend the narrative to favor your individual whims. I will repeat this in as many ways as I can think of.

The telltale sign that an argument is laced with entitlement is double standards. To spot them, you have to look for the overlap of opinion.

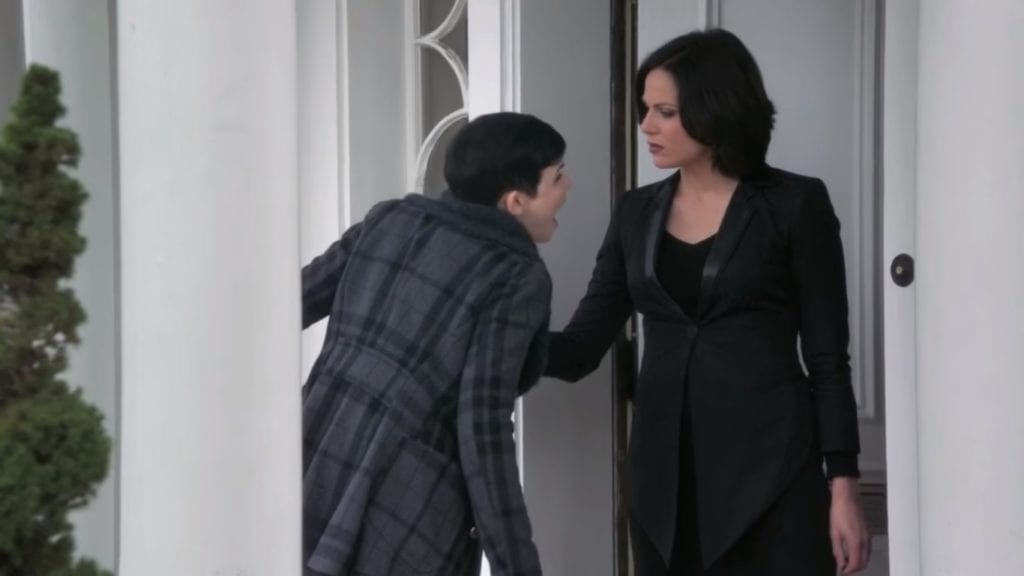

There is a running argument in the Supercorp fandom about Lena’s relationship with James being unhealthy and toxic because he used to judge her for being a Luthor. I’ve noticed many of these Supercorp fans overlap with fans of Emma and Regina (Swan Queen) from Once Upon a Time (I checked). I seem to remember Regina not only judging but hating Emma and consistently trying to murder her and her family for more than a season. If Regina gets redemption for attempted murder, shouldn’t James get ‘redemption’ for unfounded suspicion?

Yeah, maybe that specific argument against James isn’t coming from a completely honest place.

There is nothing wrong with not liking how a show is turning out or what’s happening to your favorite character. There is nothing wrong with writing fix-it fics to bask in some wish fulfillment. “I don’t like it, it’s not what I wanted” is a valid thing to say. What’s not valid is twisting the facts so that you can find a pseudo moralistic justification for your criticism. Sometimes we just don’t like things, even if they don’t have bad implications.

At the same time, stories are personal for us. They help shape how we view the world, ourselves, our relationships, and so on. Way more than most people are ready to admit. I did my Bachelor theses on this, it’s frankly a bit scary.

Moreover, sometimes we do even have a personal relationship with the people creating these stories as well as other members of fandom.

It Kind Of Really Is Personal

Before fan conventions became mainstream events, before social media, it was a simpler time. For minorities, crappier times. For example, LGBT+ kids who lived in tough environments didn’t have such easy access to a safe space online, like they do now. Fan platforms have made it so much better for many people who now know they’re not alone.

There is also the direct line to the boss people. Today, we know what we want and the creators know what fans want—though remember, even fandom itself is segmented, so we don’t all want the same things—and we know they know. This adds a whole other dimension to our relationship with television. All media, really.

On top of that, fandom has actual real-life relationships with these people. Writers and actors recognize fans at conventions. They answer to and mention them on Twitter. They accept presents. They give presents back. They build trust. Creators insert shout outs into the show. It’s great. It’s also terrible.

It is the reason the crap Jason Rothenberg & Co. pulled regarding Lexa felt so much like a stab in the chest. It’s not only that they decided (or had to) kill off Lexa. It’s that when they already knew, when they had shot the scene already, they played it off as if there was hope for the fearful fans. They posted pictures from set, openly told fans on forums not to fret, that they could be trusted. That was a direct abuse of the relationship to fans social media allows for.

However, that does not mean that the decision itself—to kill Lexa, that is—was made with malice, or with a desire to hurt anyone. The fact of the matter is Alycia Debnam-Carey had to leave the show and some choice had to be made as to how to give the character an exit. We can debate whether or not it worked in on either a Doylist or Watsonian level and what the implications are, but the narrative choice itself is not the same as writers or showrunners abusing fan trust.

It Kind of Really Isn’t Personal

On the other hand, no matter how informed about fandom desires the writers are, pleasing everyone is simply impossible. From browsing a tag on Tumblr it may seem that all or most of fandom agrees with you, but usually that’s not the case. Decision-makers may debate endlessly about what to do, but ultimately they can only choose one road to go down. Once you go down a road, writing-wise, it tends to be ride or die. And I honestly believe that the overwhelming majority of showrunners and writers are genuinely doing their best with they have.

As a PSA, I would like to advise audiences to learn how to be good losers. 99.9999% of the time, a writer’s choice is not an attack on your person or your preference. But also, be a good winner, because it’s not a gold star on your forehead if you get what you wanted. We are a community, and a community works best when its members support and respect each other.

We Influence Each Other

Here’s when I get personal. I was 19 when I first discovered Tumblr. I had a lot of issues with myself back then, and Tumblr was a big relief. I felt like I’d found people who thought the way I did, not just about television (which has always been the object of my obsessive behavior) but also about life.

It’s hard to get noticed on Tumblr. Especially if you don’t write fanfiction or share fanart. There’s many opinions flying around, and I sort of felt around for what caught my attention and others’, and I emulated it. I did this without realizing it. When I look back at some of the things I posted and the (few) fights I got into… *CRINGE*. I’m especially appalled at my bold criticism of The Writers™ and what they were so obviously doing wrong.

I’m saying fandom entitlement can be contagious. We are human and fallible. I speak to my own experience as honestly as I can here. I have rationalized very harsh criticism of The Writers™ of a show when the real problem was I didn’t like that the story didn’t go my way. In retrospect, I realize my behavior was due to a desire to fit into that community.

I can’t shake my social sciences studies. The way I see it, Fandom is a subculture, and within it communities are formed around shows, characters, preferences (of all kinds), and ideals. And a community within fandom works as any other. That means there are subdivisions, allegiances, alienation, ideologies, and yup, peer pressure.

This is especially relevant if someone is isolated in their day-to-day life, like I was. Such fans are incredibly vulnerable to implicit peer pressure. Entering a fandom is the same entering any new peer group, and you want to fit in. What are the cool kids doing? What gets them friends and/or followers? Likes? Asks? Let’s do that. I know because I’ve been there.

If it was just contained to a tag on Tumblr, it would be a smaller problem. But remember, fans are more than just that nowadays. They We are participants. It’s the reason we get to have Black Lighting and bisexual Petra Solano on Jane the Virgin and that Brooklyn 99 will live to see another day.

However, as active influencers of media we do not get to pretend we get all the privileges without the responsibilities that come with it.

Great Responsibility

“Nothing exists in a vacuum.”

“Writers must recognize the implications of what they’re writing.”

“There is a responsibility inherent when you put any kind of content out there.”

These are all expressions I’ve read, ones I’ve used, ones I think everyone here The Fandomentals would agree with. It’s not just a show. It’s not just for fun. It affects us and we should keep reminding creators of this. All true! We want our voice and opinion to be taken into consideration.

But if we fancy ourselves participants, doesn’t it stand to reason that we share the responsibility?

I think yes.

This means taking care that our criticism, our demands are well founded. I’m not trying to rain on anyone’s parade. There’s nothing wrong with joking around on social media. I indulge in weekly rants about certain shows with my friends. I’m a salty A Song of Ice and Fire fan who hate watches Game of Thrones.

But if we want to start a revolution, when we address the creators to make complaints or demands, then we have to take care. We should step back and formulate our mission well. I am proud to see that here at Fandomentals the team in charge and its writers uphold high standards on this regard. It is one of the reasons I was—and am—so excited to join.

It is the same as good writing. It comes from a true honesty on the part of the writers about themselves and the truths that guide them. Jumping on the offense when we’re not satisfied will get us nowhere. If we don’t give people space to screw up, backtrack and try again, the results might be that people will stop trying. Real change is happening, and it’s up to us to keep it on track.

Remember, with great power…