Part I — Production

Introduction:

Back in September, SyFy aired an adult animated magical girl comedy called Magical Girl Friendship Squad (MGFS). The six-episode show aired on the channel’s late-night programming block, and it served as a parody and homage to classic anime like Sailor Moon. (Numerous publications, and the creator herself, also compared it to Broad City, if you want a more accurate feel for the flavor of this show.) MGFS follows the adventures of two twenty-something millennials named Alex and Daisy after they receive magical powers and are tasked with saving their universe.

When I learned about the show in January, I was surprised that I hadn’t heard about it sooner. It seemed like the perfect thing for the queer, leftist side of the Internet to fangirl over, from its female-led cast and racial diversity, to the fact that several of its characters are queer, including lead character Daisy. Indeed, the show resonated so much for me because of its casual depiction of single queer people.

Daisy is my favorite character from this show, and her voice actress, Anna Akana, is also one of my favorite YouTubers, so of course, I dove into that side of MGFS most intensely. Daisy is unabashedly queer from the first episode, and at first glance of the show, she reads as a lesbian. Two episodes also feature a trans pride flag sticker on her laptop, exciting trans viewers craving representation. Both these interpretations fall apart, however, when one goes over the show with a fine-tooth comb and when considering the show’s evolution.

The text supports Daisy being a cis woman, and a little subtextually bisexual, yet the creators laid the groundwork for viewers to interpret her as a trans lesbian. To further complicate all of this, the lead writer and Akana posted contradictory statements about the flavor of Daisy’s queerness. The subtlety and uncertainty of Daisy’s characterization reflects the complex road that creators navigate when it comes to authentically representing marginalized groups. Overall, the case interests me as it reveals how gender and sexuality come alive in the details of representation, as well as how a failure to communicate efficiently during a collaboration can mean those creators bring conflicting intents to a project.

In this piece, I will lay out the context and the Twitter discussions, while parts two and three will focus on Daisy’s gender and sexuality as presented in the text.

A Messy Magical Girl Background:

Magical Girl Friendship Squad dates back to 2015 when showrunner Kelsey Stephanides first conceived the idea for a Sailor-Moon-esque parody/homage. Eventually, the animation studio Cartuna agreed to produce the show, and Stephanides pitched this pilot series for years before SyFy picked it up in 2019. SyFy though wanted major revisions and longer run times, so the pilot series was called Magical Girl Friendship Squad: Origins and aired on January 1st, 2020, months before the official version would be released.

Diana McCorry had written every episode of Origins, and many elements from her work transferred over in the writing process for MGFS. Hallie Cantor then worked as lead writer on MGFS, but she did not write every episode like McCorry. In my opinion, McCorry should have received credit for writing or for general story elements because of how much of her work influenced the main series. It’s not unheard of for screenwriters to draft treatments or scripts that ultimately get turned down but still receive credit for ‘pre-production script development’. Besides that behind-the-scenes change, different animators worked on Origins and MGFS, for the most part. For example, Daisy’s parents and their religious background are introduced in the shows’ respective third episodes, and Rob Lynch was the only animator credited on both. The voice cast underwent significant changes too. The only voice actress who worked on Origins that returned for MGFS was Akana. In fact, Daisy remained the most consistent when looking at the changes between iterations of the story.

Origins and MGFS kickoff when a red panda named Nut approaches Alex and Daisy and offers them powers. The women gleefully accept before finding out that Nut, creator of the universe and arguably a goddess, will depend on them for protection, her earthly animal form making her weak. She also explains that they must protect the universe from monsters bent on its destruction. The narrative begins to diverge from here. Origins focuses more on the women fighting off bounty hunters before confronting the alien Verus and her boss, a Trumpian parody called the Emptier. MGFS spends more time following Alex and Daisy as they adjust to their powers and struggle as young adult women. While Verus remains a significant villain, she lingers for most of the season, as the main-cast villain was changed to being a man named Corvin. He is her assistant and the front-facing employee of her business, gathering energy for her in a plot reminiscent of the first season of Sailor Moon that had featured a shadowy Queen Beryl tasking her Generals with harvesting energy from humans. Corvin is a flaming gay man whose design recalls classic anime villains and whose voice actor Matteo Lane, is also gay.

In Origins, Alex is a biracial young woman with a white mother and an Indian father who felt inferior and competitive towards her sister. She swears and wants to party almost as much as Daisy, and in general, she is rough around the edges. She changed in the drafting process to an ambitious Black woman with a background in programming, and her character arc begins after having been fired, being forced back onto the job market. She seeks out female role models and loves easy-listening jazz. Stephanides and her team had softened those edges, refiguring Alex into the more responsible of the duo. Brianna Baker voiced Alex in Origins, and Quinta Brunson replaced her. Both actresses are Black women, so production made sure to cast someone from Alex’s background the second time.

Similarly, Nut remains emotionally aloof in Origins and speaks in spiritual monotones, stating that she is ‘sexless’, even though Alex and Daisy refer to her by she/her pronouns. The main series presents her instead as a flawed, human-like goddess that had a “weird, horny teen phase” and a past romantic relationship with Verus. She lives with the guardians in both iterations, but MGFS is the version that presents her as a third roommate and mentor.

In both series, Daisy is a queer Asian-American woman who enjoys pot and partying and who has a… complicated relationship with her religious parents. We see less of the characters’ personal lives in Origins, but Daisy is unmistakably a woman-loving-woman. She sleeps with a woman in the second episode and professes her love for Gillian Anderson in the fourth episode respectively. Similarly, in MGFS, she has several past female lovers, including an ex-girlfriend who had proposed marriage.

The most distinct difference in my opinion, besides the character’s physical design, is the fact that in Origins Daisy tells her parents that she works as a missionary for her church, while in MGFS she doesn’t discuss her job (lie or not) at all. MGFS in fact presents Alex and Daisy as more enterprising and motivated than their pilot series counterparts. Akana, an openly bisexual Asian-American woman like her character, voiced Daisy in Origins and MGFS, being the only cast member to stay. She has also been tied to the project longer than the writers for MGFS and many of the animators, setting her apart from the other voice actresses.

Considering how the story changed internally and externally factors into understanding all of the confusion regarding Daisy’s queerness. It hints toward conflicting levels of communication between collaborators, as well as how Twitter tends to filter information almost memetically.

The Twitter Discourse:

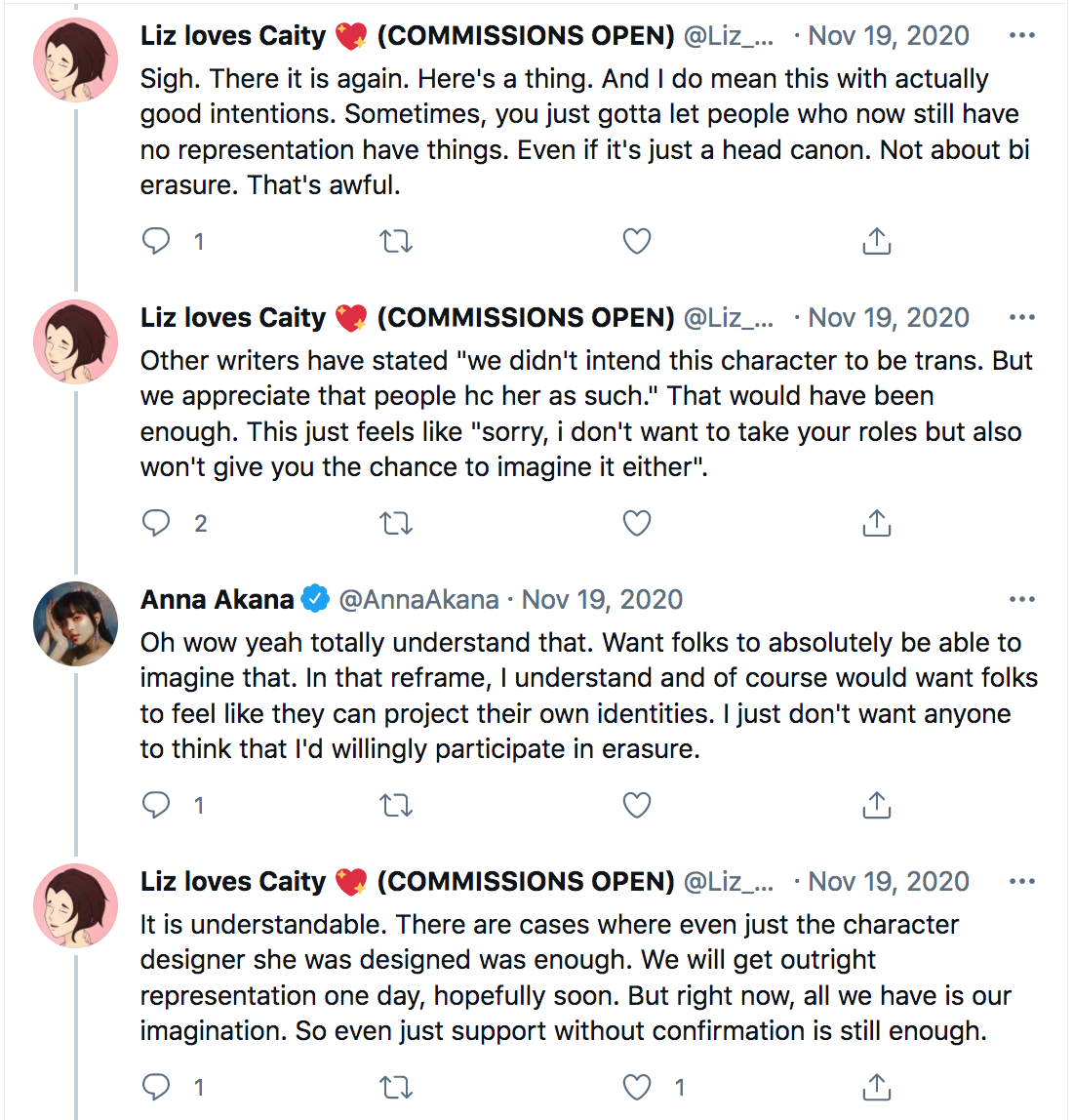

In mid-October of this past year, a young trans person tweeted a thread about trans actors voicing trans characters, noting cases in which cis actors had been cast, taking roles that could have gone to out trans people. The thread included Daisy but did not name Akana. Trans Hollywood, a political Twitter account dedicated to representation, proceeded to retweet the post and tagged Akana, writing, “[Akana] Needs to make room for a trans actor on this show.” (The account has since deleted its retweet after Akana clarified that Daisy wasn’t trans, but it was saved by the Wayback Machine, and I am citing it for context.) Akana first tweeted Trans Hollywood, correcting them, and then the maker of the thread, reiterating that Daisy was not trans but a bisexual cis woman. She further explained to Trans Hollywood, “I agree trans actors should play trans characters, but the fact that people have tried to erase Daisy’s bisexuality is equally maddening. I rarely get to play a character true to my sexuality. please don’t get your info off of random Twitter comments.”

Two weeks later on November 1st, over a separate Twitter exchange, Cantor replied to a fan’s question about Daisy’s gender and the trans pride sticker, tweeting: “As far as I know we haven’t (yet!) identified her as trans or cis, @kelseynides who created her might have a diff answer.” Her non-answer must have fueled fan speculation again as the thread which involved Akana came back up again on November 18th, leading her to discuss different types of representation with fans.

Early in the situation, a fan asked her, “My only thing is, have the writers confirmed daisy is bi and NOT trans? It feels weird for you to insist daisy is not trans just because you voice her. If daisy is bi that’s great but you’re also a voice actor and I would like some confirmation from actual creators[.]” Akana replied, “haha yes of course the writers have!! I’m insistent because I’M THE ACTOR PLAYING DAISY. I support trans rights too and I love that the animators chose to include that flag[.]”

The fan’s seeming flippancy towards the input a voice actress put into her craft reflects how our culture often forgets and devalues voice-over work, and it reminds me of how some people dismiss a singer’s artistry in their songs if they don’t have writing credits. A voice actor may not have written the actual text, but they bring the character to life and interpret the writer’s dialogue themselves, giving it its own flavor. The voice actor will also likely have had many conversations with the director, and for a lead role, most definitely the writers and showrunner. I can understand the frustration that laces Akana’s answers as fans kept ignoring what she said and the subtle dismissal of her contributions to creating Daisy.

Relatedly, some of Akana’s subsequent tweets addressed representation and her level of involvement in the project. For clarification, I gathered several of her tweets into one large quote so as to better see her response, using ellipses and brackets to note where a new tweet begins:

“I came on board [for] this project back when it was a proof of concept. I wasn’t just a hired vo actor. I was approached specifically for the role before it was even a show. So yes, I’m annoyed about the constant erasure of bisexual identity from fans who see a sticker[.] […] And the reason I’m so insistent is bc I have trans fans and I don’t ever want them to think I’d take a trans role away from a trans actor/VO artist!! […] [M]y issue is that Daisy isn’t trans and people are insisting she is bc of a laptop sticker animators gave her.

[In some other threads, I clarified that Daisy was a cis woman who identified as bisexual, which is why the erasure point has come up here] […]

An entirely diff thread insisted Daisy was trans. I said she wasn’t. That she reflected my identity; cis, bi. They kept arguing that wasn’t the case. She must be trans cause of the sticker. I said no – I play her, we have the same identities. They kept arguing & ignored– [sic] […] [M]y insistence is because I do not want trans people to think I feel comfortable portraying them in the media. I was approached for this as a queer woman to play a queer woman. […] I don’t want to take roles away from trans folks. I want them to be represented authentically. And the bisexual conversation was an additional issue that came up.”

Akana later clarified to the fan that, “People can for sure be bisexual AND trans. I’m talking specifically about Daisy!!” to reassure them after they expressed subtle disappointment, thinking Akana was implying that a trans person couldn’t be bisexual.

I would be interested to hear the animators’ thoughts on the situation and the backstory behind this sticker. The sticker was featured in an episode in which Daisy’s storyline precluded any hint of trans identity and which implied she had to hide her queerness from her parents. (I will discuss this in detail in part two.) Did the animators include the sticker as a show of solidarity from the show and/or to deepen her character, implying she was an ally? I am not going to call the sticker’s appearance as queer baiting, because, as Ladies First laid out a while back, queer baiting largely relies on the creator’s intent.

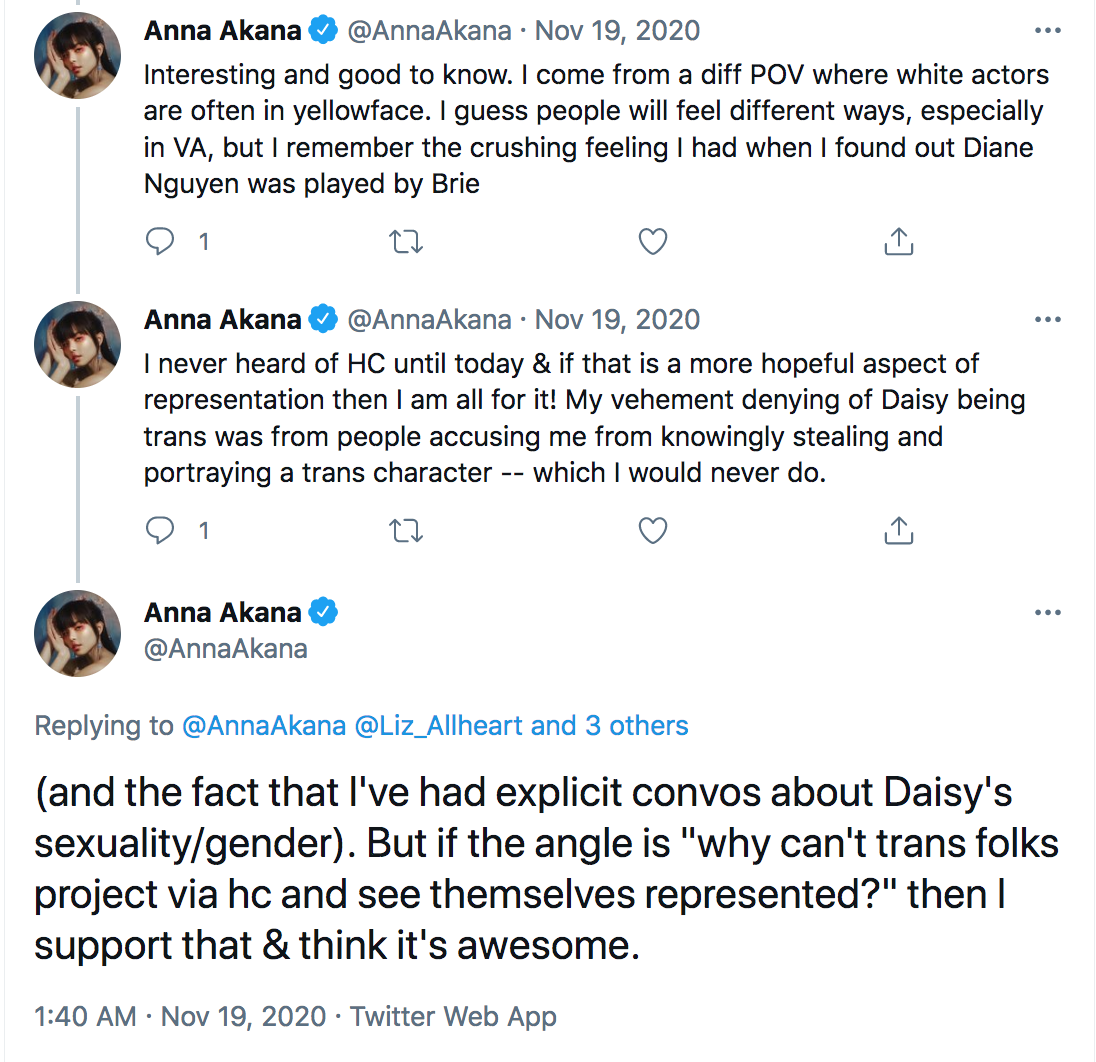

Overall, fans’ focus on the sticker highlights how powerful certain elements are in a visual medium like animation and how distinct images, in the eyes of the general public, outweigh the text, including dialogue. It also highlights how important clear representation is so as to not disappoint fans — something Akana understands well as an Asian woman in an industry that whitewashes Asian characters with semi-regularity. It’s an issue that she has discussed many times over the years, such as for her keynote speech when she won the 2016 ISA Impact Award. In the thread, she actually brings up the devastation she felt when she discovered that a white woman voiced the character of Diane Nguyen from Bojack Horseman, hence her vehemently asserting she did not speak for another marginalized community.

Different Types of Representation:

The following day, Akana and the fan talked about material representation versus headcanon potential, and her responses reveal the racial aspect of casting that informs her worldview. The entertainment industry in 2020 witnessed a significant upheaval regarding race and whitewashing animated characters via their voice actors, especially in the latter half of the year, motivated by the Black Lives Matter movement.

The bit about headcanon also reveals a difference between queer and racial representation, how society understands race in an intensely visual way. Queer people of color face stigmatizaiton from birth, long before they express their queerness (Baldwin, pp. 179-180). Coming to terms with racism and its psychological effects can even stall a queer person of color coming to terms with all aspects of their identity (Mihee Choe, pp. 21-22). Headcanoning a character’s identity in a TV show does not really work when it comes to racial politics, at least from my understanding of it. And from what I’ve seen of Internet culture, this kind of headcanoning has only applied to gender and sexuality. (Think of the numerous Tumblr blogs with titles like ‘yourfaveisgay’, ‘yourfaveisasexual’, and so forth.)

The delayed aspect of queerness, the internalization of the closet and heteronormativity, means that type of identity is processed differently and often later. I discussed queerness and representation in relation to child abuse for this reason. Akana has similarly discussed coming to terms with her bisexuality in her late twenties and how she internalized biphobia at a young age. In that same interview about bisexuality, Akana expressed commitment to addressing queer issues with the same passion she has for feminism and anti-Asian racism, particularly within the entertainment industry.

I can understand why a queer actress of color, who has spent a large portion of her career campaigning for racial progress and who described herself as a “baby queer” early last year, would approach casting and representation with race first in mind, not taking into account fans’ headcanons. All of these Twitter exchanges serve as an example of the fact that clear communication, compassion, and giving the other party grace for the most part, matter more than ever. We live in fractured, violent times, and if we are ever to improve our communities, we need to have more conversations like this, while acknowledging the complexities of people’s experience.

Transfeminist scholar Julia Serano coined the term “trans-unaware” to describe the average person’s understanding of trans issues, writing that these people typically are “passively transphobic” (e.g., only expressing such attitudes when they come across a trans person, or when the subject is raised), and may be open to relinquishing those attitudes upon learning more about transgender lives and issues.” A similar framing can be applied to issues such as race and feminism, at least on an individual level, person to person. We can also see Serano’s definition play out in real-time between Akana and the fan.

Though the issue of Akana portraying Daisy started out rough because of a bad tweet, and though questions remain on how the other creators on the show got from point A to B regarding that sticker, it also shows change happening in real time.

Check out part two next week for analysis of Daisy herself and her story in Magical Girl Friendship Squad!

Images courtesy of Cartuna and TZGZ Productions

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!