So, listen. I don’t feel great about the fact that I really like Shelob and want her to live a long, happy life. I mean, yes. Spoilers. She gets a pretty nasty stabbing next chapter. But I’m sure she’s fine. You don’t become Shelob the Great, weaving webs of shadow and vomiting darkness and then get taken out by a stomach wound. She’s probably found herself a nice, new, filth-cave somewhere. Some awful, nasty crevice where she can eat and brood in peace, into the Fourth Age and beyond. Her mom would be proud, had she not eaten herself ages ago.

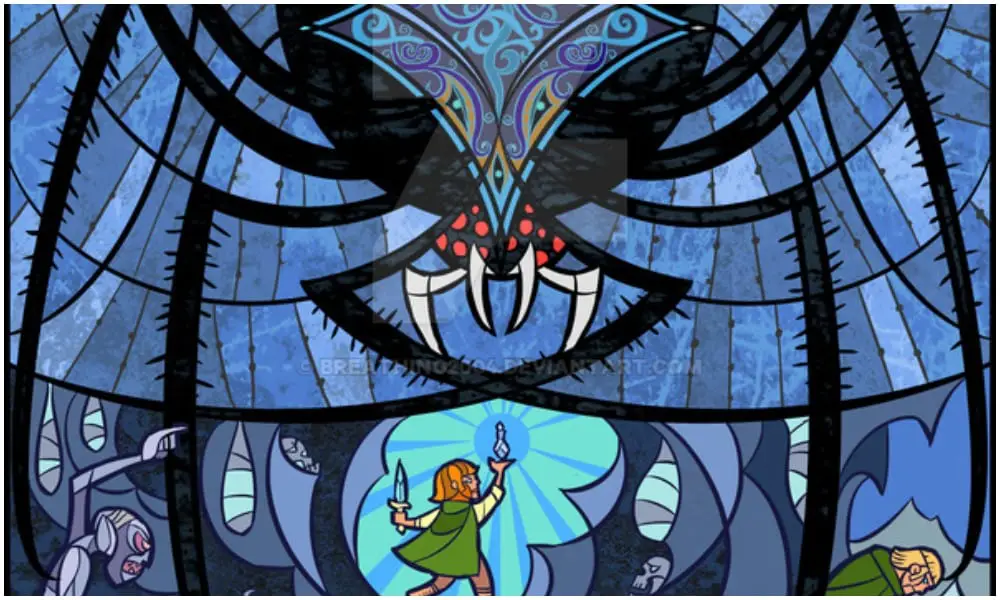

Shelob is a delightful villain. In peak Tolkien-y fashion she manages to be a B-movie monster and metaphysical treatise on evil, a spider-monster-of-existential-dread. Her attempted attack on Frodo and Sam is a battle of light and darkness. This could have been a frustratingly clichéd fantasy trope. Good and evil, light and dark. Not the most exciting trick in the book, though a giant, heaving spider-monster will take you far. But “Shelob’s Lair” also manages to transcend these limitations. Because Shelob herself – what she is – raises all kinds of interesting questions about Tolkien’s world and how it works, and his attempts to apply a mosaic of Christian metaphysical principles to Middle-earth in ambiguous, occasionally paradoxical ways.

Night Was All

The hobbits’ arrival in Torech Ungol is the atmospheric culmination of the last two chapters’ fading light. The sun had already been eclipsed two days earlier as the hobbits made their way towards Minas Morgul and atop the staircase “a grey blurring shadow shrouded the stony world about them.” Minas Morgul and that stairs up Cirith Ungol were aberrations: twisted versions of what they had been before, dimmed and distorted. Shelob though, and her tunnel, are an absence.

Not since the lightless passages of Moria had Frodo or Sam known such darkness, and is possible here it was deeper and denser. There, there were airs moving, and echoes, and a sense of space. Here the air was still, stagnant, heavy, and sound fell dead. They walked as it were in a black vapor wrought of veritable darkness itself that, as it was breathed, brought blindness not only to the eyes but to the mind, so that even the memory of colors and forms and of any light faded out of thought, Night always had been and always would be, and night was all.

Shelob and her lair are not the perversions of good that we so often see in Tolkien’s moral universe. They’re the absence of good, or the cloaking of good. Shelob is a fundamentally different kind of evil than Minas Morgul or Sauron himself. And she challenges the idea that Tolkien’s moral universe is lacking in nuance. Instead, it’s a Christian one – particularly a Neoplatonic one – with all the thorniness and complexities that millennia of metaphysics would suggest.

Colors and Forms, Light and Darkness

We’ve talked about Neoplatonism around these parts before – particularly when we took a look at Lórien. Neplatonism is a messy, multifaceted philosophy, but that Christian brand that we’ll discuss here has a couple of key traits. It tends to operate on the assumption that individual objects of the world are simply reflections of ideal, heavenly forms. Frodo observes this in Lothlórien:

A light was upon it for which his language had no name. All that he saw was shapely, but the shapes seemed at once clear cut, as if they had been first conceived and drawn at the uncovering of his eyes, and ancient as if they had endured forever. He saw no color but those he knew, gold and white and blue and green, but they were fresh and poignant, as if he had at that moment first perceived them and made for them names new and wonderful.

Torech Ungol is nearly the antithesis of this depiction of Lórien. Not only is it dark, but it erases form and light: even the memory of colors and forms and of any light faded out of thought.

This use of light and darkness is also a common element in Neoplatonic thought, since its works so nicely as a moral analogy. Rejecting a dualism common at the time of its conception – a dualism that would posit a long-lasting battle between Good and Evil – neoplatonism instead assumed the total oneness and omnipotence of God. And it assumed that absolutely everything in the universe stems from God and his creation.

This unity and comprehensiveness, though, led to a tricky philosophical question: how to explain the presence and pervasiveness of evil? If all stemmed from God, shouldn’t everything be good? Neoplatonists tended to answer this by conceptualizing evil as an absence. Evil was not a tangible power, but the lack of good. People were not moved to do evil. Rather, they failed to do good.

Shelob and the Issue of Evil

Tolkien himself expressed it in a 1956 letter to W.H. Auden: “In my story I do not deal in Absolute Evil. I do not think there is such a thing, since that is Zero.” The Lord of the Rings is filled with “evils:” instances of people falling away from goodness in search of power or the elimination of difference. Sauron and Saruman are both examples, Morgoth the prime one if you move over to The Silmarillion. Shelob, though – following her mother Ungoliant – is in some ways the closest that we get to Tolkien’s Zero. Shelob is absence, a dark, consumptive force.

Tolkien goes so far to this extent that at times it feels as if he is contradicting his initial conception. Shelob can feel less like an absence of good and more like a dark power in her own right.

But other potencies there are in Middle-earth, powers of night, and they are old and strong. And She that walked in the darkness had heard the Elves cry… far back in the deeps of time, and she had not heeded it, and it did not daunt her now. Even as Frodo spoke he felt a great malice bent upon him.

Her mother, Ungoliant, was the same. When she helped Melkor destroy the Two Trees of Valinor, she did it by covering them both in “Unlight, in which things seemed to be no more, and which eyes could not pierce, for it was void.”

It’s fun to ponder precisely how Shelob fits into Tolkien’s moral universe – whether as force unto herself, as a symbol, or as a scary spider lady (or, hey, all three!). I think there are ways to make it fit. Jonathan McIntosh has a lot of interesting thoughts for you, should you be interested in a 54-part (!!) series on Tolkien’s metaphysics. But on the narrative level of Lord of the Rings, Shelob works on a different level. She’s a final stumbling block to this leg of Frodo and Sam’s journey, nearly a manifestation of the despair that’s been their barely-at-bay fourth companion since the Dead Marshes.

A Light When All Other Lights Go Out

The interiority of Frodo and Sam’s struggles in Book IV of The Two Towers is something that we’ve touched on a few times. It can make this leg of the story feel listless for readers more fond of Book III. There is, after all, quite a lot of walking. That sort of narrative pacing is my jam, as I’m sure you’ve all been able to tell. That said, it’s immensely satisfying when so many of the general tensions and themes of the past few chapters become externalized as a giant spider monster with claws and thorns and scary, many-windowed eyes.

Frodo has had to deal with issue of despair since Emyn Muil. The isolation of their quest after being broken off from the fellowship, the looming reality of approaching Mordor, and the persistent reminder of Gollum’s current mental state made the audacity and danger of Frodo’s mission unavoidable. Frodo spends much of the book in a kind of prolonged flinch. Sam keeps him going. And that’s why the progression fo their encounter with Shelob plays out so well.

Then, as [Sam] stood, darkness about him and a blackness of despair and anger in his heart, it seemed to him that he saw a light; a light in his mind, almost unbearably bright at first, as a sun-ray to the eyes of one long hidden in a windowless pit. Then, the light became color: green, gold, silver, white. Far off, as in a little picture drawn by elven fingers, he saw the Lady Galadriel standing on the grass in Lórien, and gifts were in her hands.

It’s a clever passage, as if some power is rolling back the effects of Shelob and recreating Lorien. The darkness gives way to light; after light comes color, then shape. It makes sense that this restoration comes to Sam first – always a bit heartier than Frodo in the face of despair. But Sam can only sense what to do – it’s Frodo that has to do it.

Slowly his hand went to his bosom, and slowly he held aloft the Phial of Galadriel. For a moment it glimmered, faint as a rising star struggling in heavy earthward mists, and then as its power waxed, and hope grew in Frodo’s mind, it began to burn, and kindled to a silver flame, a minute heart of dazzling light, as though Earendil had himself come down from the high sunset paths with the last Simaril upon his brow. The darkness receded from it, until it seemed to shine in the center of a globe of airy crystal, and the hand that held it sparkled with white fire.

The Phial of Galadriel works so nicely in this chapter. In the wrong hands it could have been a boring deus ex machina. Frodo remembers his magic weapon, pulls it out, and then passively stands there as elf magic fights spider magic. But Frodo is active in its use, his own hope required to kindle its full power. It works doubly well with the invocation of Earendil. Not only does it nicely call back to Frodo and Sam’s discussion of continuing stories in “The Stairs of Cirith Ungol,” but it also ties together Frodo and Earendil: two people persisting in the face of impossible quests. And with all of this tied together, Frodo – so often battered and weighed-down in Book IV – gets a moment of pure, active bravery.

Then Frodo’s heart flamed within him, and without thinking what he did, whether it was folly or despair or courage, he took the Phial in his left hand and with his right hand drew his sword. Sting flashed out, and the sharp elven-blade sparkled in the silver-light but at its edges a blue fire flicked. Then holding the star aloft and the bright sword advanced, Frodo, hobbit of the Shire, walked steadily down to meet the eyes.

It’s a bright, satisfying moment, well-earned in the wake of so much struggle. Good old Frodo. <3

Final Comments

- Before Sam receives his vision of Galadriel, he thinks of the barrow and of Tom Bombadil. This not only neatly ties together the mythological weirdness of Shelob/Ungoliant and Bombadil, but it also sets up a nice parallel of Frodo picking up a sword to face down something much more powerful than him.

- I like the explanation of Sauron’s and Shelob’s relationship. It seems very fitting that he would view her as a funny kind of pet. It also seems fitting that she wouldn’t think of him at all. It’s a shame she never got to eat him. Is there Shelob fanfiction? Of course there is, but I bet there’s not enough.

- After a few failed attempts and some fervent clutching of my own metaphorical phial of Galadriel, I managed to make myself google, through folly and despair and courage, the phrase “shelob feminism.” The first result, which should not surprise me, was an MRA forum (do not click, would not recommend). In any case, I understand the arguments for and interpretations of Shelob as a misogynistic character. But I’m also not sure that I entirely agree. She’s such a frightening, interesting villain, unique in a way that can only be compared to Tom Bombadil (who gets a shoutout here by way of Sam). Honestly, sometimes I wonder if Tolkien stuck Shelob and Bombadil into his legendarium solely to baffle beleaguered theologians.

- On Shelob’s spider origins in the story: “If [Shelob] has anything to do with my being stung by a tarantula when a small child, people are welcome to the notion (supposing the improbable, that anyone is interested). I can only say that I remember nothing about it, should not know it if I had not been told; and I do not dislike spiders particularly, and have no urge to kill them. I usually rescue those whom I find in the bath! Well now I am really getting garrulous. I do hope you will not be frightfully bored.” J.R.R. Tolkien to W.H. Auden, June 1955

- “Shelob’s Lair” always makes me think of “The Bridge of Khazad-dum.” Both short, action-heavy chapters; both well-paced and filled with ominous bits of prose. I’ll always dearly love “too little did he or his master know of the craft of Shelob. She had many exits from her lair.”

- Gollum’s reappearance at the chapter’s end is very visceral and upsetting. He jumps on Sam from behind – just as Sam sees Shelob closing in on Frodo – wraps his hands around his throat, and spits on his neck. It’s a frightening moment even in the context of wall-to-wall spider action. Just filled with a sense of immediate violence and powerlessness. Sam’s ability to fight back sets the stage for his actions in “The Choices of Master Samwise.”

- Prose Prize: There agelong she had dwelt, an evil thing in spider-form, even such as once of old had lived in the Land of the Elves in the West that is now under the Sea, such as Beren fought in the Mountains of Terror in Doriath, and so came to Lúthien upon the green sward amid the hemlocks in the moonlight long ago. How Shelob came there, flying from ruin, no tale tells, for out the Dark Years few tales have come. But still she was there, who was there before Sauron, and before the first stone of Barad-dur; and she served none but herself, drinking the blood of Elves and Men, bloated and grown fat with endless brooding on her feasts, weaving webs of shadow; for all living things were her food, and her vomit darkness. Far and wide her lesser broods, bastards of the miserable mates, her own offspring, that she slew, spread from glen to glen, from the Ephel Dúath to the eastern hills, to Dol Guldur and the fastnesses of Mirkwood. But none could rival her, Shelob the Great, last child of Ungoliant to trouble the unhappy world. I love this so much. Shelob’s weird hype track. She’s so gross, and so great.

- Contemporary to this chapter: Faramir retreats from Osgiliath; Théoden and Aragorn get a little closer to joining the fray. The Ents keep their undefeated record and beat back an attack on Rohan (an attack I’d entirely forgotten about).

- In two weeks – “The Choices of Master Samwise,” Teenage-Katie’s favorite chapter.

Art credits: Film stills are from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) courtesy of New Line Cinema. All other art, in order of appearance, is from Jian Guo (he returns!) and Ted Nasmith.