Welcome back, Tolkien friends! I have been simultaneously looking forward to and dreading this chapter. Denethor is one of the most interesting characters in The Lord of the Rings, but his path to despair is also one of the most critically well-tread. For my part, at least, the definitive character study on the guy has already been written. Who am I, really, to try to top the idea that Denethor is the Richard Nixon of Middle-earth ? So please, go there, go read it.

Daniel Stride nicely outlines what’s up with Denethor. He’s traditional and old-fashioned to a fault, he’s a political realist in a word that has little respect for such philosophies, he’s insecure to an extent that it manifests as paranoia. He is lonely: his wife died long ago, he lost one son only a few weeks back, now another lies dying at his feet. And seeing his line die out, and black sails sliding up the Anduin in the surface of the palantír, Denethor does what he’s famous for in The Lord of the Rings: he despairs.

The Basis of Choice

Stride’s article is so great at explaining who Denethor is, and why he does what he does. But there’s more to be said surrounding how Denethor’s choices fit into Tolkien’s broader world and its themes. And it starts before Denethor even appears on page—when Pippin finds Gandalf in the wake of the Black Rider’s departure, and begs him to save Faramir.

“Can’t you save Faramir?”

“Maybe I can,” said Gandalf, “but if I do, then others will die, I fear. Well, I must come, since no other help can reach him. But evil and sorrow will come of this. Even in the heart of our stronghold the Enemy has the power to strike us: for his will it is that is at work.”

It’s such a Tolkien-y choice: an echo of Aragorn’s choice to chase Merry and Pippin rather than continue on the assumed route of the quest, of Frodo’s choice to spare Gollum and trust him rather than to leave him tied up in the name of his own safety (and Middle-earth’s). All of these are open to criticism. That Aragorn’s choice to follow one set of hobbits put at risk the “more important” set. That Frodo’s faith in Sméagol’s redemption was at the potential expense of all Middle-earth. Or that Gandalf’s choice to save Faramir doomed Théoden and countless unnamed riders who died in the shadow of the Witch-King. They are criticisms—particularly the last—for which I have quite a bit of sympathy.

In Tolkien’s moral world, of course, these choices are correct. Good choices aren’t based on strategic sacrifice or the rational extrapolation of possibilities. Instead, a good choice is a rejection of utilitarianism, the choice of a person over an abstraction. It’s not on your shoulders to map out the potential paths of the world and choose the best one. You simply do what you can in the moment. You save the person you love. And that brings us around to Denethor.

Hope is But Ignorance

Denethor, as everyone in The Lord of the Rings, is given a choice. His final scene in the Houses of the Stewards at Rath Dínen is a tight parallel to Gandalf’s arrival at Meduseld to confront the aging Théoden, full of disdain and despair. “Take courage, Lord of the Mark,” he says. “For better help you will not find. No counsel have I to give to those that despair. Yet counsel I could give, and words I could speak to you. Will you hear them?”

Gandalf offers a similar choice to Denethor, another aging ruler who’s lost a son: set aside his “madness” and return to the world and those directly around you. After all, he tells the steward, “there is much that you can yet do.” Both men waver for a moment in the face of their choice. And then each turns in opposite ways.

Hope, in Tolkien, has a direct interplay with knowledge—or presumed knowledge—of the world. Théoden slips into despair as he’s fed information from Wormtongue. And Denethor makes his grand assertion of defiant despair as soon as he whips out his palantír and reveals what he’s seen.

“I have seen more than thou knowest, Grey Fool. For thy hope is but ignorance. Go then and labor in healing! Go forth and fight. Vanity. For a little while you may triumph on the field, for a day. But against the Power that rises there is no victory. To this City only the first finger of its hand has yet been stretched. All the East is moving. Even now the wind of they hope cheats thee and wafts up the Anduin a fleet of black sails. The West has failed. It is time to depart for all you would not be slaves.”

My first time reading this chapter this time around, it was tempting to see Denethor’s despair as simply a condemnation of overreaching knowledge and pride. Denethor sought for knowledge about his pay grade and destroyed himself; the faithful little hobbits, oblivious to the world and its highest machinations, are rewarded by the powers that be for their plucky ignorance.

But knowledge is a tricky thing in The Lord of the Rings. It’s not condemned or written off as shady goal of upstarts who don’t know their place. Pippin’s curiosity is an asset (mostly). Faramir’s curiosity to learn more of the world under Gandalf’s tutelage—though distrusted by Denethor—is framed as a virtue. But it’s also so dangerous: learn a little, and you think you know a lot. Because Denethor does know a lot about the current situation, more than anyone else save perhaps Aragorn and Gandalf. His palantír assured him of that. And this knowledge sets him down the path of two Tolkienian (…?) flaws.

Pride and Despair

“Do I not know thee, Mithrandir? Thy hope is to rule in my stead, to stand behind every throne, north, south, and west. I have read thy mind and its policies. Do I not know that you commanded this halfling here to keep silence? That you brought him hither to be a spy in my very chamber? And yet in our speech together I have learned the names and purpose of all thy companions. So! With thy left hand you wouldst use me for a little while as a shield against Mordor, and with the right bring up this Ranger from the North to supplant me. But I say to thee, Gandalf Mithrandir, I will not be thy tool! I am a Steward of the House of Anárion. I will not step down to the dotard chamberlain of an upstart.”

Denethor’s most obvious failing on his road to despair is simply the misinterpretation of the information he’s given. He distorts information wildly through his own presuppositions and fears, his insecurity a permanent lens on the palantír. Pippin, to Denethor, could only be a spy: why else would Gandalf bring him? Aragorn could only be an affront, an attempt to destabilize, change, uproot. Sauron’s army must be infinite and unstoppable; black sails could only be the Corsairs of Umbar coming upstream to complete the final sack of the city. A little information, in short, makes Denethor think he knows too much.

This, for Tolkien, is a forgivable flaw. Pride is something that can be worked against, insecurities are something that can be overcome. The two in tandem always make for a yikes combo, but hey! who are we to be too eager to deal out judgement in Middle-earth? Even the very wise cannot see all ends. And it’s there, really, that Denethor gets into trouble. It’s not knowledge that trips him up into despair so much as the flaw that plagued both Sauron and Saruman: a failure of imagination.

The End Beyond All Doubt

“What then would you have,” said Gandalf, “if your will could have its way?”

“I would have things as they were in all the days of my life,” answered Denethor, “and in the days of my long-fathers before me: to be the Lord of this City in peace, and leave my chair to a son after me, who would be his own master and no wizard’s pupil. But if doom denies this to me, then I will have naught: neither life diminished, nor love halved, nor honor abated.”

Denethor’s failure, in the end, is not so much rooted in knowledge, fear, or pride (though none of them helped). Rather, his despair is rooted in myopic certainty. The world, for Denethor, falls apart or it stands. It continues on, like old rusty clockwork, powered by honor and tradition, continuity and peace: having been saved by him, by Gondor. Or it is destroyed. These are the only options Denethor can imagine, in a clear-cut world built on rickety scaffolding in which Denethor has unshakeable certainty. Gandalf himself hinted at the danger all the way back at the Council of Elrond, when defending his plan for the Ring: “It is not despair, for despair is only for those who see the end beyond all doubt. We do not.”

Denethor, of course, thinks he does. And he becomes, in short, is the deepest sort of Tolkien tragedy: he can’t even imagine the eucatastrophe. He lives in a world where they are inconceivable. And it’s this element that sentences him to failure without redemption in Tolkien’s moral universe.

This is something that, on one level, I get. In Middle-earth, and in what I’ve gathered from Tolkien’s Catholicism, such a failure of imagination is not simply a flaw but a wholesale rejection of reality. A rejection of eucatastrophe is putting a crack in the whole nature of the world. But at the same time—while not condoning Denethor’s unilateral decision to set his sick son on fire—it’s impossible for me not to be sad at his end, or not to wish that he had gotten some kind of comfort, redemption, or solace. Denethor’s story is such a lonely one. And while much of that was his own making, the fact that he truncates his own story so definitively and in such isolation makes him a tragedy that’s unique in The Lord of the Rings, and one that will always make me sad.

Final Comments

- Potentially-controversial opinion time: I do wonder if Gandalf was too harsh on Denethor. When Faramir calls out his name in a dream, Denethor “started as one waking from a trance, and the flame died in his eyes, and he wept.” I am a softy but this seems like a moment where Denethor could maybe have been comforted and pulled back from despair through love for his son. Gandalf decides to go for the, uh, hardball route. He tells Denethor to go fight on the Pelennor and that maybe he’d see his son later if they should both manage to survive. I see where Gandalf is going with this. But whenever I read this section it feels like a lost opportunity.

- When Pippin hears the horns of the Rohirrim, they “break his heart with joy.” Afterwards he is unable “to hear a horn blow in the distance without tears starting in his eyes.” This is lovely, and make me think Pippin will be a very sweet old-man hobbit.

- It’s interesting to me that Denethor goes up in flames and envisions “The West” as burning into ash. I wonder if Denethor, well-versed in Gondorian and Númenorean lore, used this metaphor purposefully as an inverse of Númenor’s historic trouble with flooding. Or maybe it was because Sauron had a big volcano.

- Tolkien had some interesting thoughts on Denethor in his letters (letter 183). “Denethor was tainted with mere politics: hence his failure, and his mistrust of Faramir. It had become for him a prime motive to preserve the polity of Gondor, as it was, against another potentate, who had made himself stronger and was to be feared and apposed for that reason rather than because he was ruthless and wicked. Denethor despised lesser men, and one may be sure did not distinguish between orcs and the allies of Mordor. If he had survived as victor, even without use of the Ring, he would have taken a long stride towards becoming himself a tyrant, and the terms and treatment he accorded to the deluded peoples of east and south would have been cruel and vengeful. He had become a “political” leader: sc. Gondor against the rest.” In some ways Denethor feels like a modern leader in a rather un-modern story.

- I was lucky enough to be over in England earlier this month for an academic conference (medievalists of all stripes gather in Leeds each year to drink beer, talk history, and pad that CV, ammirite?). On the long bus ride back down to my flight in London I stopped by Oxford and its Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth exhibit at the Bodleian Library. If you happen to be in the area, it’s a really lovely exhibit (with a dangerously great gift shop). I was especially struck but how good an artist Tolkien was, and how frequently his works would stray into the geometric or quasi-psychedelic. I want to post them here but I fear the wrath of the Tolkien estate, so just go here to get the info you need to google braver bloggers who laugh in the face of copyright violation.

- The next road trip, inspired by managing super-editor Kori, will presumably have to be to Bloomington, Indiana to find more information on this Lord of the Rings script written by John Boorman. I am both slightly relieved and utterly crushed that this was never produced.

- Prose Prize: It’s a dialogue-heavy chapter, and my favorite is probably Denethor’s response to Gandalf’s query on what Denethor actually wants, from above. It’s antithetical to Tolkien’s views but also cased in such an elevated language that it almost feels noble. Perfect for Denethor.

- Contemporary to this Chapter: We’re in near-exact parallel to last chapter, which works nicely. All of this occurs as Théoden makes his stand and Éomer experiences eucatastrophe.

- Mytly’s Corner of of Wanton Cruelty to Punctuation is having its definition stretched this week: no dramatically long sentences with six semicolons but I was deeply annoyed by “for his will it is that is at work” from Gandalf’s comment to Pippin above. Tolkien! Please. “it is that is?” Why? Stop. Wanton cruelty to syntax and aesthetics.

- Tired by this week’s downer of a chapter? Please come back next week for some steamy Faramir-Éowyn romancing as they stand on battlements and think about hope. Yeah!

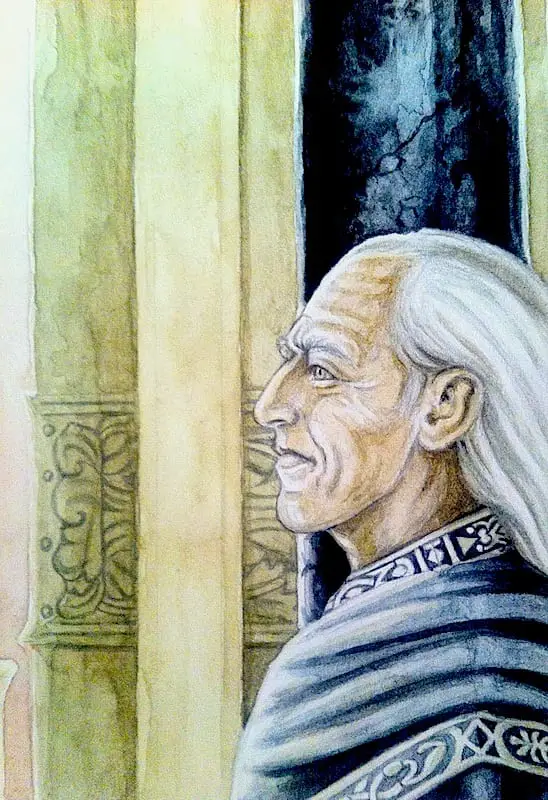

Art Credits: All film stills are from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), courtesy of New Line Cinema. All other art, in order of appearance, is from Ted Nasmith, Lorenzo Daniele, and Peter Xavier Price.