Disco Elysium is a game that appeared unexpectedly by the tail end of 2019 and made quite the splash. This game by the small studio ZA/UM received plenty of praise and award nominations. Did it deserve them? I think it absolutely did. It’s not a flawless or perfectly-designed game, but it’s unique. It has spirit. It has something to say in this age of polished, safe mediocrity. But what makes it so special? Let’s find out.

The game begins with deep blackness and nothingness. There’s only two voices — one belonging to our ancient reptilian brain, and the other to our limbic system. We have a brief, and rather confusing, conversation with them. It sets the tone for the entire game.

Once it’s over, we see our protagonist. He’s lying face down in the middle of a wrecked hotel room, in his underwear. Thus our first goals become very simple. Find our clothes. Find our shoes. Once we find one shoe, we set out to find the other one, which we apparently threw through a window. We can look into a mirror, but we won’t like what we see.

Much like in Planescape: Torment, our hero has absolutely no clue who he is, how he got there or what his name is. Unlike Torment, however, the reason isn’t very mysterious. It very likely has to do with the empty bottles littering the place and the mother of all hangovers he’s feeling. A conversation with a young woman outside his room reveals some more details of his epic three-day drunk bender, but little more than that. So we set off to do what we’d come there to do.

That’s about as much as I will say about the story, since discovering everything as we go along is where all the fun is. Nor will I say much about the setting. I will say that it’s not our world, but it resembles it. The world of Disco Elysium is an odd blend of aesthetics. It may resemble France from the 70s, but there’s also a Soviet feeling to it I found hauntingly familiar (even if I’m too young to truly remember it).

The city we’ll explore bears the scars of a failed revolution. The consequences of it are fresh in people’s minds. We’ll meet people of different backgrounds and fictional ethnicities. The issues of race and class will come up time and again and we can take sides on them… or don’t.

How To Disco

But let’s move away from such spoiler-prone territory. What does this game actually play like? It’s very much like an old-school isometric RPG in terms of appearance. In terms of gameplay, it could be described as a combination of that and a point-and-click adventure game. Or, if you will, Planescape: Torment without any combat.

A long time ago, I wrote an article about how that game, well-deserved though its stellar reputation may be, is held down by a ruleset that is not only bad but also ill-suited to its purpose. A game about searching for truth using rules about adventurers in dungeons. I asked a question: how would one design mechanics specifically for a game like Torment? Well… Disco Elysium is how.

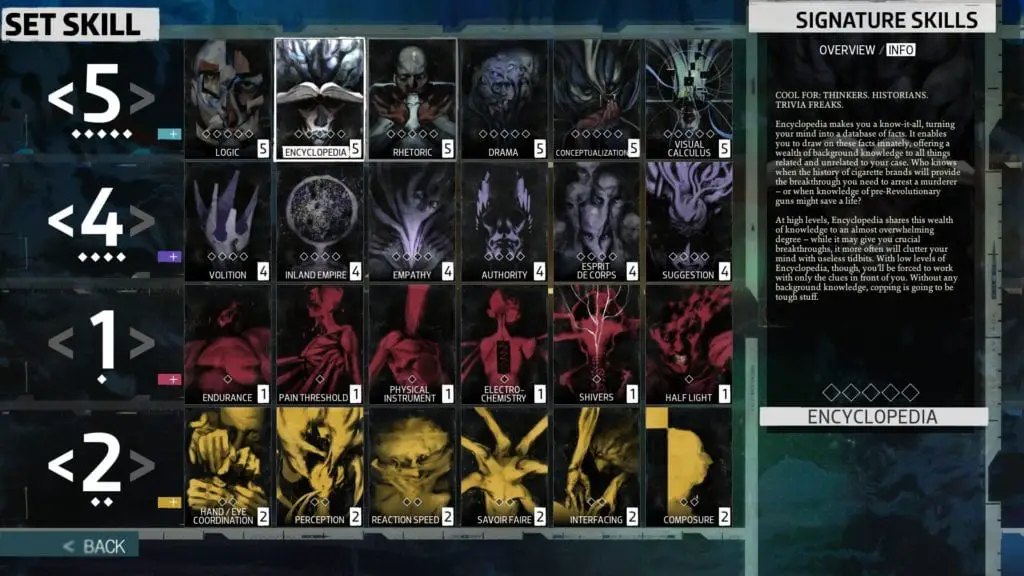

Disco Elysium uses a set of 24 skills. They come in four sets — Intellect, Psyche, Physique and Motorics. Some of them are very obvious, like Rhetoric, Suggestion, Endurance and Perception. Some are mundane but have unusual names, like Half-Light (intimidation and threats) or Savoir-Faire (agility and speed). Others still are very esoteric, like Inland Empire, Shivers or Conceptualization.

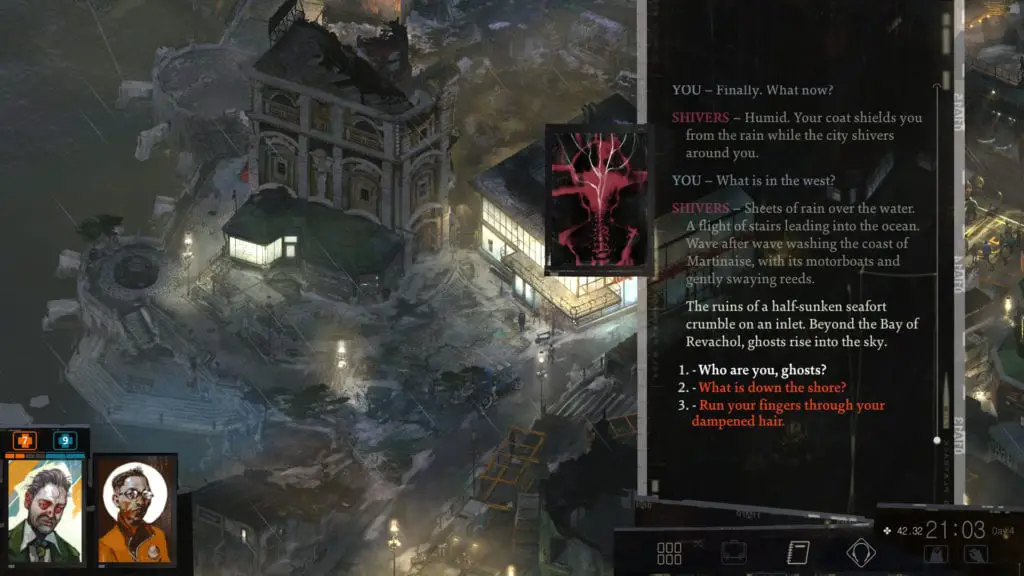

Like I said, there’s no combat in this game. No tactics and no reflexes are required of us. There’s just dialogue — between us, other people, the world and our own psyche. Whether we talk, investigate, use objects or just think really hard, the dialogue interface will be our tool. The skills, however, aren’t just tools in it. They are active participants.

Yes, that is correct. Our skills talk to us. They’re not just abilities — they’re a part of our personality. Sometimes it’s innocuous enough. “Encyclopaedia” will explain some facts to us, while “Empathy” will tell us what’s hiding behind someone’s words. But sometimes it gets deeper, and we’ll have entire conversations with our skills. They’ll suggest things to us — and they might not be good ideas.

In more practical terms, we have two kinds of checks, active and passive. Active checks simply roll dice behind the screen. The game tells us how likely we are to succeed beforehand. They might be white or red checks — in the first case, we can retry them after failure if we invest in the skill or sometimes if we find new information. In the latter, we only get this one shot.

Passive checks simply depend on our skill value. If it’s high enough, we get additional information or help. They are, however, hardly dry bits of information. Our skills present their insights in their own unique ways, according to their personalities.

They might be more or less accurate – or not accurate at all – but they will be colored by their biases. A lot of the time it feels like it’s a conversation with many participants… but only we can hear most of them. The skills’ voices are a constant backdrop. The higher a skill, the more often and more forcefully it will chime in. This creates a feeling that our character thinks differently depending on his skillset.

It’s difficult to put into writing, but the mechanics of the skills flow together with the game’s narrative very seamlessly. Unlike with other games, there’s never a break in the story so we can fight or do something else. We just proceed, make choices and then encounter opportunities to use skills. While there’s no combat as such, violence may happen — but it’s dealt with using the dialogue window.

Is it flawless? Well… not quite. For one thing, some skills are just a lot more useful than others, at least in my experience. We use them frequently, while others less so. That’s a rather common ailment of RPGs, isn’t it? Furthermore, if we fail a check, nothing stops us from reloading and trying again. This dilutes the tension a bit. That said, sometimes there’s several difficult checks spread across a lengthy dialogue section. So if we reload to retry one check, we can fail another one that we did pass. It’s the game’s equivalent of “boss fights”.

In addition, failing a check obviously doesn’t mean our progress grinds to a halt. There’s always another way, it might just not be advantageous or easy. Sometimes it means blundering around or putting ourselves in trouble.

Like Torment, Disco Elysium is a game about searching for truth. We try to unravel the mystery we’re tasked with, but also our own past. As well as numerous other side-tasks, in the best tradition of role-playing games. However, many of the seemingly irrelevant our outright inane encounters, conversations and side-tracks will end up being quite important indeed.

Thus it really pays off to explore, poke around and talk to people. The game’s area is small but rich, something I appreciate. Every character can meet and talk to has their own story, which may relate to our own past, investigation or the country’s history. While it may feel to other characters like we’re wasting time, it won’t feel this way to us, the players.

Time, I should note, is something of a resource. The game has an internal clock and hours pass as we move through it. Morning becomes noon and then evening falls. Depending on the time of day, different characters and places may become inaccessible or the other way around. However, time only passes when we choose dialogue options. Simply walking around doesn’t advance it even by a minute. This lets this element be pleasantly realistic instead of applying pressure.

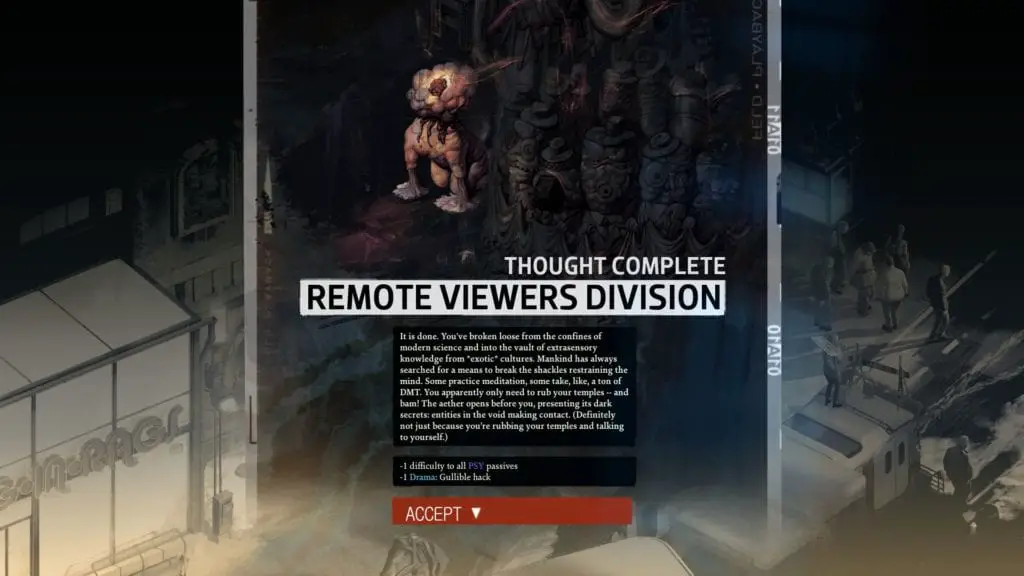

A very curious feature that bears mentioning is the Thought Cabinet. During the course of the game, we will have thoughts on various topics. We can then internalize those thoughts using our Thought Cabinet. Which thoughts we get frequently depends on our choices. Internalizing a thought takes time and often gives us penalties to skills while we do. Once it’s finished, we receive benefits, but often also penalties, as well as insights about some part of the story.

This element of gameplay is, sadly, rather imperfect. We have a limited number of slots for thoughts, and have to buy further ones with experience. While internalizing a thought, we can take it out and save it for later, but once it’s finished, it’s stuck there. We have to pay extra experience to remove it, and then it’s gone for good. Since benefits from thoughts can be very much a double-edged sword, we can end up paying XP to internalize a thought and then pay it again to get rid of it.

Another thing that will help us make checks and use our skills is clothing. Different articles of clothing give us bonuses and penalties, so we will often dress up for the purposes of a specific check. Which will result in rather… original combinations. Our protagonist has a shabby, haphazard look regardless of what he wears, though.

Disco Elysium really is one of a kind and I sincerely hope it proves an inspiration to the rather stale RPG genre. It shows that a truly story-driven game is possible, while keeping RPG mechanics. And it does so in its own quirky, philosophical, off-beat style. You will not regret trying it.

You can pick up Disco Elysium on Steam or GOG.com

[rwp_box_criteria id=”0″]

Images courtesy of ZA/UM