The Discworld series doesn’t exactly need a lot of introduction. My previous article about it, quite a while ago, had the tone of disappointment. So today I’d finally like to write about why I love Discworld in the first place and how it shaped how I view fantasy. And that is its ground-level view. Not, there’s no shortage of “gritty” fantasy, but such a view tends to be tinged with grimdark. I think Discworld does something unique with it.

How it began

Of course, it wasn’t always like this. It’s hard to talk about Discworld without acknowledging that the series saw major changes over time, and the world we see in the earliest books is sometimes hard to reconcile with the one later on.

Early Discworld has shades of what I’m describing, but it’s still a fairly direct pastiche of the fantasy genre. It focused on fantastical and especially magical elements a great deal. There’s still a down-to-earth element to it, to be fair. It’s more in the vein of satire and jokes, but nonetheless.

The words “ground level” explicitly appear in one particular book—Small Gods. It’s one of the more popular Discworld, books, frequently held up as one of the better written. It tells us a story of the god Om, who was once a voice on the wind before managing to gain belief, and thus power. But then he suffered the fate of many other formerly-small gods whose belief simply ran out. People began to believe not in him, but in the oppressive theocracy around him. He still has one believer, though, which lets him persist in the form of a tortoise. Miserably.

When he later gains another surge of belief and thus a second chance—most small gods don’t even get the first one—he still, “can’t stop thinking at ground level.” Travelling with Brutha, his last worshipper, gave him a perspective that is normally alien to gods, namely, that all the small people they fight wars over matter. The greatest of gods see mortal lives as a game because hey, they’ll all die in a couple of decades anyway. Brutha espouses a different view, which Om comes to share and literally beat into the other gods: here and now, they’re alive, so it’s not a game.

The lowly City Watch and the big city

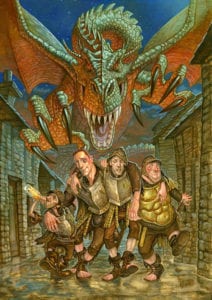

But that’s getting ahead of ourselves. When does the ground level start? Opinions will differ, but to me the book where it really comes into its own is Guards! Guards!. The initial idea for the book was to put the spotlight on the unfortunate souls who tend to meet their end valiantly attacking a hero one at a time as he swings on a chandelier.

Now, having down-to-earth protagonists wasn’t exactly new to the series. Rincewind was an inept coward who just wanted to be left alone, which is why he resonated so much with me. But he was still, technically, a wizard. Or wizzard, as the case may be. Mort, Eskarina Smith, and Teppic all had something special about them, one way or the other. Granny Weatherwax, Nanny Ogg, and Magrat are all witches… though they have a role to play here too, more on that later.

The Night Watch of Ankh-Morpork are the lowest of the low… except for Carrot, that is. But Carrot doesn’t end up the viewpoint character, Captain Samuel Vimes does, and it’s hard to get more ground level than he is. And not just because we first see him lying down in the gutter.

At the end of the book, Lord Vetinari makes a speech about the nature of people. It’s cynical, and Vimes doubts it somewhat because Vetinari still gets up in the morning. But part of it is that after the dragon is defeated and the villains routed, life goes on. People will still expect someone to take the trash out.

The City Watch sub-series continues to be perhaps the best study in what I’m talking about, though by far not the only one. This is due to Vimes and Carrot both, in addition to the rest of the cast. Vimes comes from Cockbill Street, whose inhabitants try all their lives not to slide into the Shades and maintain their smattering of dignity. Later on, beaten down by life, he becomes a drunkard—not rich enough to be an alcoholic—who’d given up on everything.

Throughout the sub-series, we watch him get out of the gutter both metaphorically and literally. But he remembers where he came from. And whenever he looks at Ankh-Morpork, he still sees it from the point of view of the streets. And his own old, leaking boots that can feel the cobbles underneath.

Corporal, later Commander, Carrot has a parallel but different view to Vimes. Unlike the old cynic, Carrot is relentlessly idealistic. He’s also the heir to the throne of Ankh-Morpork and has tremendous charisma. Bags of it, as Sergeant Colon would put it. And yet, he doesn’t take the throne, nor does he use his charisma as much as he could. The biggest display is in Men at Arms, where he single-handedly assembles a militia.

But in that same book, he explains to Lord Vetinari why he won’t take charge. It’s because people should do the right thing because it’s the right thing, not because Carrot tells them to. Because Carrot is nice and easy to obey. This is a more clever deconstruction of heroic narrative than usual. In the earlier Discworld books, Pratchett goes for more direct ways. The barbarian heroes are greedy thieves, Rincewind is a coward…but Carrot really is everything you’d expect from a hero. And that’s why he won’t simply step up, woo the crowd, and take the throne. Because you can’t just treat people like puppets every day.

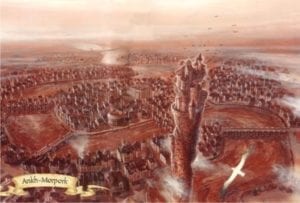

The city of Ankh-Morpork in general is one of the most living and breathing fantasy settings I’ve seen. Let me use a quote from Night Watch to illustrate it.

“Vimes had a vision of Ankh-Morpork. It wasn’t a city, it was a process, a weight on the world that distorted the land for hundreds of miles around. People who’d never see it in their whole life nevertheless spent their life working for it. Thousands and thousands of green acres were part of it, forests were part of it. It drew in and consumed … and gave back the dung from its pens and the soot from its chimneys, and steel, and saucepans, and all the tools by which its food was made. And also clothes, and fashions and ideas and interesting vices, songs and knowledge and something which, if looked at in the right light, was called civilization. That’s what civilization meant. It meant the city.”

In Art of Discworld, Pratchett expresses his dissatisfaction with many fantasy cities. They don’t feel alive to him. Ankh-Morpork is an attempt to rectify that, and I believe he succeeds. Night Watch, I think, encapsulates what I’m talking about very well. It shows a revolution from the point of view of the street, and a man who already knows how it will end. But he has to see it through, because he won’t leave those people to their fate.

Bearing in mind, of course, that for all that the Ankh-Morpork books focus on “the people,” that doesn’t mean they have a very positive focus. Indeed, Pratchett is rather merrily brutal in showing us the uglier side of the teeming masses of humanity. Or dwarfdom and trolldom, as the case may be. He likes to point out that people with perfectly functional higher brain capabilities can come together and become a mob, whose intelligence equals the IQ of its dimmest member, divided by its number of participants.

The mob ignores what’s important in favor of frivolities… but then, what really is important? It’s like Vetinari said in Guards, Guards! to the people: the important thing is to put food on the table and stay safe. It won’t help them much that the rightful king has returned if they can’t have that. Which, of course, doesn’t stop them from believing that everything will be fine and peachy as soon as they have a king again.

It’s that signature mix of cynicism and optimism Pratchett has. At the end of the day, people will be people, with their ups and their downs. They’re not the unwashed masses oppressing the exceptional people, nor are they good, kind-hearted salt of the earth. They’re just people. Take them or leave them.

The magic

Still, that’s the vast and tumultuous metropolis of Ankh-Morpork. What else is there in terms of how Discworld shows fantasy at ground level? There’s two more ways I’d like to mention, both magical in nature. The first relates to magic as practiced by wizards and the second is tied into the books that concern the witches of Lancre and the young Tiffany Aching.

In the early Discworld books, magic is fairly typical for fantasy. It takes centre stage, whether it’s in the form of wizards or other supernatural phenomena. Rincewind is incredibly inept as a wizard and incapable of any actual magic, but actually competent magicians play a part. Later on, it scales back gradually.

Pratchett establishes that the largest obstacle to magic running things is witches and wizards themselves, as something in the study of magic makes them as likely to co-operate as ornery cats. So the energy they could use to stage a takeover is spent fighting each other. Except for Sourcery, that is.

In Wyrd Sisters, Granny Weatherwax says something else that I think is a foundational for how Discworld would treat magic. Namely, that if you use magic to take control of or fix things, you’re going to have to keep on using it until it’s magic running things and not you.

What this morphed into is the idea that the most important skill in magic is when not to use it. Not because it’s difficult, but because it’s easy. If you use it whenever it’s convenient, you’ll soon find yourself with more than you’ve bargained for. As Archchancellor Ridcully put i, if you sling spells like there’s no tomorrow, there probably won’t be.

This subdued approach to magic isn’t unique in fantasy, which is an amazingly broad genre after all, but it certainly contributes to Discworld’s ground-level atmosphere. In Art of Discworld, Pratchett voiced a rather curious opinion: magic isn’t interesting. When a wizard snaps his fingers and makes light, he says, he’s just doing what wizards always do. But a pack of monkeys weren’t doing what monkeys usually do when they dismantled the world and put it back together to make a lightbulb.

A lot of fantasy treats magic as the focus in itself. Pratchett’s approach puts the focus on the people, with magic being just a tool to bring out conflicts. When magic-users appear, they’re still people, first and foremost.

Rincewind, of course, isn’t an actual magic-user in any practical sense. The wizards of the Unseen University are, at first, a rather unstable cast, what with with their propensity for murdering each other. Later on, after the introduction of Mustrum Ridcully, the cast stabilizes as he foils multiple assassination attempts and everyone mostly gives up.

The wizards go on to become prominent characters, but not strictly speaking protagonists. The Last Continent is an exception, as their point of view appears alternately with Rincewind’s. They also appear in the Science of Discworld spin-off series. Their main appeal isn’t so much magic as their group dynamic, full of absurdly abstract conversations, bickering and long suffering from Ridcully and poor Ponder Stibbons.

The land in your bones

The witches are a different story. They have a series of books that focus on them, starting with Equal Rites, which nonetheless has a different feel to it than later ones. Wyrd Sisters starts the sub-series properly. Granny Weatherwax and Nanny Ogg are two very powerful witches who don’t do all that much magic. What magic they do can be often hard to tell apart from just being clever.

Granny is a fascinating character in her own right, of course. She stands firmly on the side of good because she’s too proud not to. Not unlike Samuel Vimes, who has his own inner policeman to keep him on the straight and narrow.

Whereas the wizards of Unseen University tend to diffuse their otherwise destructive magic potential with politics, inane arguments, and eating a lot, witches are as down to earth as you can get. They heal, they advise, they protect. Their magic is subtle and under the skin, as opposed to wizard magic, which is big and flashy when it happens.

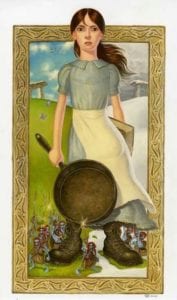

Tiffany Aching, who enters the series in Wee Free Men, is likewise a witch. She doesn’t live in Lancre, but Granny Weatherwax and Nanny Ogg do enter her stories and many of the themes intersect. In the first book, it’s said that witches don’t appear in Chalk, Tiffany’s homeland, because the ground is too soft and a witch needs solid rock. This turns out not to be true, as there is solid flint under the chalk. Thus Tiffany can be a witch, like her grandmother had been.

Witching coming from the rock, hard to get more ground level than that, is there? Tiffany’s series concerns itself with land, community, and defending what’s yours, even more so than the books taking place in Lancre. Witches mingle with society more than aloof wizards, but they still live on its fringes. They’re never really a part of it. The people rely on them, but never quite let them in.

Both Lancre and the Chalk are societies that live and breathe, much like Ankh-Morpork. But they’re its opposite, in a way. Where the Big Wahoonie moves at a hectic pace, with fashions, outrages, and politics appearing quickly and disappearing even more quickly, Lancre and the Chalk are slow and steady. Their inhabitants don’t change their minds easily. Or at all.

Once again, this is shown as both positive and negative and all around “take it or leave it.” People can be stupid, petty, cruel, or just plain bad, but you can’t just up and change them with magic or kingly destiny. Otherwise you stop treating them as people and start treating them as things. And that, as Granny Weatherwax would tell you, is where all that’s bad has its start. In treating people like things.

Discworld has had its ups and downs, but in the end, it became a grounded fantasy series that’s really one of a kind. It has changed the way I see the genre. There’s always this voice in my head saying “Okay, but how does it work? What’s it like to live there? What does the average person really worry about? Is magic actually more real to them than it is to us?” Sometimes I will listen to this voice, sometimes I’ll ignore it and just suspend my disbelief. But I’m glad it’s there. And for that, I have Terry Pratchett to thank.