I was eleven when Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings film trilogy was released. I, like the millions of others who saw it, was immediately swept away into a secondary world that would take hold of me and never let go. These stories spoke to me like nothing I had ever heard. They were my favorite things. My mother, who had read the books when she was in college, said she’d be happy to lend me her copy of the trilogy, but suggested I start with something a bit simpler (I was eleven and a very mediocre reader) like The Hobbit. She explained to me how the story took place sixty years prior to the events of The Lord of the Rings and was actually written as a stand-alone novel before the trilogy was ever conceived. It’s the tale of Frodo’s uncle Bilbo and his adventure to reclaim a dwarven kingdom that’s been commandeered by a ferocious dragon. Count me in.

So not so unexpectedly The Hobbit, Or: There and Back Again became one of my most cherished worldly possessions and helped shape the person I am today.

Fast forward to November 2017 when Amazon announced that it would be making a “Lord of the Rings prequel series,” I wanted so badly to be filled with excitement when it was announced. After all, more Tolkien is good Tolkien, right? But why did I have such a bitter, hesitant feeling about new content being created? There is so much material created in the Middle Earth legendarium that spans far and wide from the content in the Lord of the Rings. Content that could be beautifully retold if it were in the hands of the right storytellers. I mean sure, there will be hiccups and cause for concern as far as keeping the integrity of the Tolkien estate unspoiled, especially with Christopher Tolkien announcing his retirement. But taking ideas and narratives and trying to sell them to a consuming public is not inherently a bad thing, and I’d like to think I look at the availability of more Tolkien stories as a potentially good thing…

That’s when it all started flooding back to me: we’ve been down this road before, haven’t we? We’ve seen what can go wrong when a giant studio conglomerate decides to capitalize on popular narrative trends and ends up butchering a folktale beloved by millions in order to pump out blockbuster numbers. I thought I blocked all that out, what was it, four, five, six years ago respectively? Perhaps my optimism for more Tolkien content is just naïveté in disguise.

The Hobbit: An Unexpected Trilogy

I’m talking of course about The Hobbit. This three-part CGI fest, bought and paid for by Warner Bros made its way into existence and caused an absolute uproar with Tolkien fans and filmgoers everywhere. From the beginning it seemed doomed, or at the very least polarizing: Del Toro dropped the project, leaving the production team to scramble and revamp their entire vision, and when Peter Jackson moved from Executive Producer to Director, he made the choice to turn the 270 page folktale into an epic trilogy, shooting it with new 48 frames-per-second technology.

With the hype surrounding the project due to the success of Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Hobbit was sure to be a massive undertaking that would require the utmost care and respect in terms of its presentation. But that’s not what fans were given. In its entirety, The Hobbit Trilogy became the messy, shallow spectacle that every self-identified member of a fandom dreads.

Was this all just a perfect storm of bad timing and poor decisions? Maybe. Are these films just more glaring evidence to why “prequel trilogies” and “extended film universes” are a terrible idea? Perhaps, but there are plenty of arguments against that. One thing is for sure though, much like Peter Jackson’s Rings trilogy, The Hobbit was at the forefront of a film industry crossroad. Technology had made exciting and groundbreaking strides that enable stunning visuals and thrilling modern tools to aid in their story telling. Peter Jackson & Co are known for constantly pushing boundaries and playing with new tricks, but when it comes to making spur-of-the-moment experiments done at the behest of the Middle-Earth Universe—a universe which they had a major role in shaping, by the way—they were bound to piss some people off.

So, my dear Bagginses and Boffins, what exactly went wrong with the Hobbit Trilogy? What went right? Let’s dive into The Hobbit’s first installment, An Unexpected Journey in this three-part essay that examines the films. In the back of our minds we can hope that while Amazon creates their new Tolkien content, they will learn from the mistakes, and hopefully capitalize on the successes of their predecessors by exploring new, exciting ways to tell stories while (hopefully) being respectful to its source material.

Unpacking the Prologue: My Dear Frodo

Having an expositional prologue to an epic trilogy isn’t a terrible idea on paper. It gives us viewers a chance to ease into the experience and informs us on key plot points/names that are going to continuously pop up. But The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (AUJ) in particular has extra weight already attached, that is, to reintroduce us to the already beloved Middle Earth Universe. When AUJ begins, we are immediately given recognizable music cues and the comforting voice of Ian Holmes as Bilbo. The choice is clear: these films will not only be of the same vision and universe as the Ring’s films, but will act as a compendium, a bridge between themselves and the films that came before them.

The choice to begin the films as a meta-narrative though, is more distracting than it is helpful. It’s fine to use the same actors, sets, styles, etc. within The Hobbit narrative (Gandalf, Elrond, etc.) because the stories obviously belong together. But, to contrive a scene that takes place in the time of Frodo and the Ring of power is tacky, and the constant insistence to call back to The Lord of the Rings only serves to hurt the story you are trying to tell. The mantra of “you can’t really compare The Hobbit to The Lord of the Rings,” flies out the window when you begin your entire story as a HOMAGE TO THE LORD OF THE RINGS.

So, we revisit Bag End and the Shire, but it’s not the Shire we left at the end of Return of the King, nor is it the Shire we were introduced to in Fellowship— it’s unfamiliar to the senses. This goes back to the advancement in technology and the decision by Jackson & Co. to shoot The Hobbit in 48fps rather than film. The coloring is saturated, the details are crisp and polished rather than weathered and mysterious, and—not that they can do anything about it, but—it’s so obvious that both Ian Holmes and Ian McKellen have aged a decade. No amount of makeup and 3D magic can hide this.

But could the film have started any other way? What other options were there to set the scene? Could we really have been thrown into the same (stylistically) beloved version of Middle-Earth without acknowledging the giants of which these films are standing upon?

In my mind, this could be an obvious answer to why Del Toro dropped the project. Imagine creating a film based upon a beloved novel that is also living in the shadow of the most successful fantasy film franchise to date. Imagine wanting to have a creative vision, but the studio heads and executive producer are constantly adding things and pushing deadlines and reminding you of the fact that in all honesty, these will never be your films, they’ll just be an extension of Jackson’s Middle Earth Film Universe. It’s unsurprising that Peter Jackson was the only one capable of taking on these films, unsurprising that he wanted to make them a trilogy, unsurprising that he’d want to connect them into the same film franchise he’s already made, and unsurprising why the first 13 minutes of the film amount to an over-indulgent spectacle oozing with nostalgia (and the extended version is even longer!).

So what other options were there? Let’s muse.

- Jump right in and omit the prologue altogether. Begin the way the novel does—the way your first delightful scene with McKellen and Freeman begins—by dropping Gandalf and 13 dwarves right at our doorstep, and revealing exposition as the plot progresses. Sweep through Bag End with the familiar fiddle-and-flute sounds we know and love, perhaps following Freeman through the house and out the door as he stuffs his pipe full of tobacco before he is joined by the wizard.

- In The Fellowship of the Ring, the prologue is narrated by Galadriel, a seemingly omniscient narrator setting the scene, until we reconnect with her in Lothlorian and the audience gets this wonderful realization that she has laid out the narrative in character, and we realize that she’s introduced us to the shire because she knows that hobbits will soon “shape the fortunes of us all.” Why not have her character introduce The Hobbit narrative in the very same way, since we will be seeing her in Rivendell at the white council? This would avoid the meta-narrative trope of “older Bilbo” while still giving us the information we need on Smaug, Erebor, Thorin, etc…

- Tell the prologue from a dwarf’s perspective—mainly Thorin, or Balin, or even Ori, who was the last dwarf to make record in the Book of Mazarbul, and could very easily be recording events with Balin on their journey to Hobbiton. You could even bring that into the narrative later as a character moment and make a connection with Bilbo, who will of course be recounting his own tale as “There and Back Again.”

- Gandalf narrates while he recounts the events on his way to Hobbiton.

- Frodo narrates the prologue (we got Elijah on board!), reading through his Uncle’s notes like a kid peeking at Christmas presents. He finishes just in time for Uncle Bilbo to tell him to “get his sticky paws off.”

- Martin Freeman as Bilbo pours over maps and his contract with the dwarves in Bag End. He’s going over the plot points with the audience as he debates whether or not to join the company. When the subject of Gandalf arises, that leads into his recalling of the opening “Good Morning!” scene. The plot then catches up as we see Bilbo running out the door after “Misty Mountains Cold” is sung.

Each of these concepts would pose their own set of problems. Introducing the narrative through the eyes of the dwarves, for instance, would rob the main character of ownership to the story. But the route Jackson & Co have chosen, having two different actors play the same character, poses 2 glaring issues. The first is that it disconnects us emotionally and visually from the character when you split him up, because Ian Holmes’s Bilbo already has his own separate narrative apart from Martin Freeman’s. The second issue is that wherever and whenever the story ends, we know we’ll have to revisit this established scene as the other bookend to the narrative. And it’s not that this storytelling aspect can’t and hasn’t worked before, it’s that the meta-narrative concept is completely dropped until the very end of the last film, so it feels disconnected. Ian Holmes doesn’t check in with us for 9 hours. Not once.

The best solution to not having the first half of this film slog therefore, are to either 1.) omit the prologue altogether, or 2.) have Ian Holmes continue the narration throughout the entire trilogy. Option 2 certainly wouldn’t give us the same tone of Rings, but I’d argue that as a good thing. Having an omniscient narrator we know and love come along the journey with us and making comments in all the right moments would deliver a lighter, more whimsical tone closer to the way Tolkien wrote the novel in the first place—probably the same way Bilbo might have told it—with joyful wit and authority.

Now, we finally get to have that chance, but it’s not treated as a full-on meta narrative because Ian Holmes disappears, and AUJ makes the grave error of assuming you already know and care about his character. And let me be clear, I do care very much about Bilbo Baggins in every form he has taken, but this decision doesn’t aid in the storytelling at all, it only hinders it. What it ultimately does is prolong the actual narrative in an effort to force these films at all cost, and sometimes undeservedly so, to sit beside your box set of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy, even though the original Hobbit narrative was never meant to live up to such a task.

There Are Far Too Many Dwarves in My Dining Room!

So the actual narrative begins after 13 long, expensive, rather over-stimulating minutes of dragon fire and dwarven lineages and armies and Elijah Wood cameos. Martin and McKellen have wonderful chemistry in their first encounter together (good morning!) and the scene is a joy to watch. The dialogue kept very close to the cheeky and whimsical source material, and the actors gave us a stellar opening to our story. Freeman could not have been more perfectly cast as our hobbit, and I fell in love with Bilbo almost immediately.

In fact, the casting as a whole throughout the entirety of the Tolkien Universe has been marvelous, and though I’m always nervous about the politics of television and actors and contract lengths etc, I’m sure Amazon has clout enough to wrangle up the proper talent for a series based on JRR Tolkien’s work. If not, I’m certainly available for casting.

Speaking of casting, when we get to meet our large cast of dwarves, the segment is rather like the source material, so it flows with a certain organic rhythm.

The Dwarves’ entire character development throughout the rest of the trilogy, however, can be summed up in their entrances (quite like the novel) to Bag End: Balin, Dwalin, Kili, Fili, Thorin (later) and…the rest just fall on top of one another in an unrecognizable blur of prosthetics and fake hair. Okay so Bofer has plenty of wonderful character moments, as do many of them, but having this many members of the party to keep track of poses a challenge to the film-maker and viewer alike. I’m the type of fan who already could name all 13 dwarves off the top of his head, plus had done speculative research about which actors were playing which dwarves, what types of weaponry would they use, and what their designs would be like. But not every person viewing these films is going to want to get on my level.

At the end of the day there is only one major question you need to ask yourself in order to determine whether or not there were too many dwarves to keep track of: what did they want? On an individual level, what did each of these characters want? The only answer to be found across the board for all 13 companions: they want to reclaim Erebor. We are given hardly any individual motives, nothing that might get in a particular character’s way. No disagreements, no hiccups (other than getting there, of course, and battling Smaug when they arrive), so they are all one unit, and that never really changes.

In Fellowship, companions come together from very different backgrounds in order to aid the Ring Bearer on his quest. They all have different ideas of how to get where they are going. They all have different motives as to why they joined the fellowship. Most importantly for the viewers sake, they learn to work as a team along the way and grow together after suffering great loss through conflict. It’s these things that invoke the suspense, drama, and emotion that make Tolkien stories so wonderful to experience.

And yes, The Hobbit, a folktale written for JRR Tolkien’s ten-year-old son as a bedtime story is not going to have near enough emotional complexity as that, but you’ve (addressing Jackson & Co now) elected to “darken up” The Hobbit and draw us back into your complex film universe filled with danger and evil and excitement and political complexity and racial tension. You have a responsibility to create a main cast (other than Bilbo and Gandalf) made of more than just cardboard.

Nobody Tosses The Dwarf!

Okay, if we’re talking Tolkien’s dwarves in the order of their integral plot function in the novel, AUJ goes along pretty well with it: Thorin, Fili, Kili, Balin then the rest…maybe Bomber in the book. But the film obviously can’t hide behind the alliteration and rhyming schemes that group them together, so they needed to flesh out thirteen different heroes and make them all unique, distinguishable, and functional. They all need backstory and relationship dynamics, otherwise the audience won’t want to spend time with them. Yikes that’s an undertaking. And while I appreciate the fun superficial details they added for all 13 dwarves such as Bifer speaking Kaza-dun and Gloin using the same type of weaponry as Gimli… I’d so much rather have sacrificed some number of dwarves in order to streamline the story and lesson the dwarf-recognition-fatigue and over stimulation that so many casual viewers (“we call you normies”) experienced. I know, I know, Tolkien purists everywhere just gasped, but let’s have another thought experiment:

Can we eliminate some of these dwarves based on a super scientific method I used throughout the trilogy I like to call the Scarlett O’Hara experiment? This referring to a quote from George R.R. Martin’s “Not a blog” where he uses Gone with the Wind as an example to address his fans’ concerns about the omission of characters in HBO’s Game of Thrones.

“How many children did Scarlett O’Hara have? Three, in the novel. One, in the movie. None, in real life: she was a fictional character, she never existed.”

So, based on how many lines each dwarf had, how many close-up reaction shots, overall importance to the plot, plus also whether or not they were cool, useful party members, killed baddies, and, if we care about their struggle throughout the trilogy, we can make a pretty decent judge of which characters… get the axe.

Here is our Company of Dwarves sans Bilbo and Gandalf…who are not dwarves.

- Thorin: Heir to the throne of Erebor. Leader of the Company. Warrior

- Balin: Wisest in the group and closest confidant to Thorin. Warrior

- Kili: Last in line of Durin. Youngster. Heart throb with impulsive nature. Archer

- Dwalin: Strong leadership qualities but heavyhearted and quick tempered. Tank.

- Fili: First in line after Thorin. Youngster. “gun enthusiast” of the group. Warrior.

- Bofer: Jester with a heart of gold. Comic relief. Minor.

- Oin: Eldest in the group. Healer.

- Dori: Sensitive and thoughtful. The group’s lighthearted moral compass. Dandy.

- Ori: Baby of the group. Useful for jokes, also carried the journal found in the mines of Moria.

———————————————————————————————————————

- Gloin: Father to Gimli… the “hoarder” of the crew. Warrior.

- Bomber: Fat jokes. Fun ways to play with action sequences. Tinker.

- Nori: Adept at breaking into things and has a cool beard. Lockpick.

- Bifer: Doesn’t speak common tongue, has an axe protruding from his skull. Warrior.

Let me reiterate that I personally don’t find it necessary to cut the company down if you were going to conceptualize them as interesting individuals. However, Jackson & Co elected not to film all the intriguing character backgrounds their actors created for themselves. So let’s say all those below the line, let’s call it the Line of Durin (ha) would be omitted from the film; tossed out of the company. Gloin you say? Gimli’s father? You ruthless braggart, how dare you! Okay, so I wouldn’t cut the character all together, I’d combine aspects of Oin and Gloin into one dwarf and double the moments of John Callen’s enjoyable performance recast as Gloin.

The rest of the dwarves, though they add enjoyable moments and plenty of personality to the story, are superfluous to the plot of the film, and like with Oin and Gloin, their character traits and moments could be divided up amongst the rest of the gang. Maybe you make Dori, who the actor proclaims as the dandy of the group, and also possess Bomber’s hobbit-like appetite, since that’s a direct quote from the book.

“Just when a wizard would have been most useful, too,” groaned Dori and Nori (who shared the hobbit’s views about regular meals, plenty and often).

-The Hobbit p. 30

Maybe Ori, the quiet, bookish dwarve can also speak several languages such as Kaza-dun, which would theoretically serve them well when they are in Goblin Town. 9 dwarves with tons of interesting quirks, skills, and moments over a period of 3 epic adventure films would be a much more manageable party, and would enable us to delve into who each of these characters are other than just their names and which weapon they carry. They’d be more than just walking personality traits, and the script would have more time for Bilbo to uncover their backstories, ideals, inner conflicts, motives, quarrels amongst one another–you know, things that make the fantasy characters we love interesting.

All Good Stories Deserve Embellishment

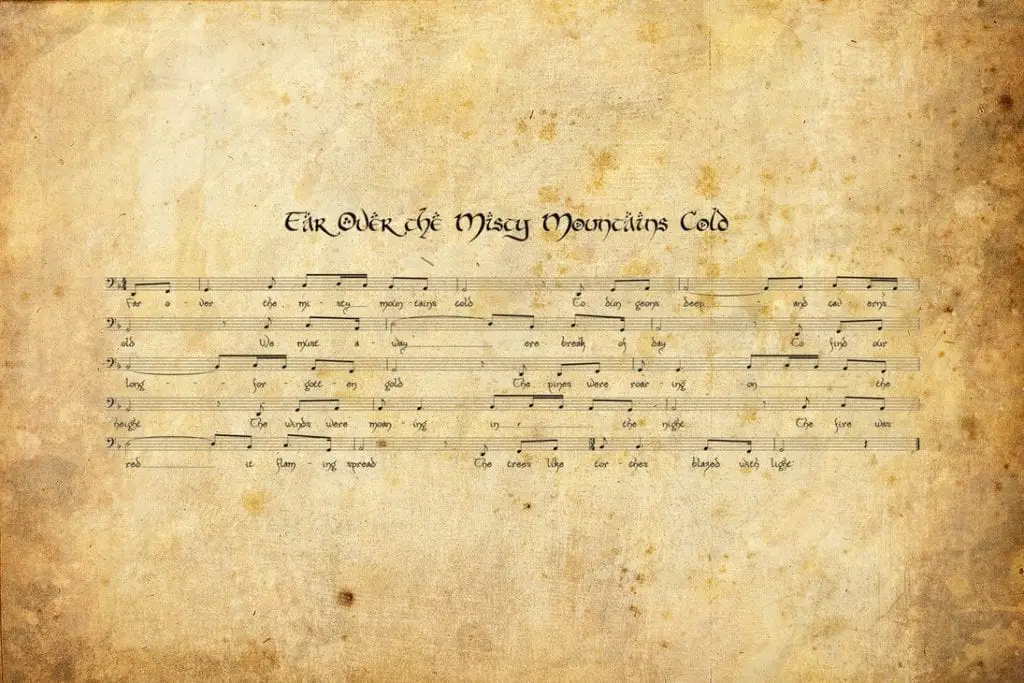

We also have two complete musical numbers which, Amazon, if you are listening, is SO important in Tolkien storytelling:

There was Eru, the One, who in Arda is called Iluvatar; and he made first the Ainur, the Holy Ones, that were the offspring of his thought, and they were with him before aught else was made. And he spoke to them, propounding to them themes of music; and they sang before him, and he was glad.

-“The Music of the Ainur,” The Silmarillion

According to Tolkien, there was God, then the offspring of God, then song. So, you know, let’s have as much music as we can to aid in our storytelling. Jackson & Co have always been good about that.

We probably could have forgone the ridiculous CGI piling of dishes in “Blunt the Knives,” but overall it was fun and silly and worked well to juxtapose the grim mood set by Oakenshield’s arrival. This is followed by one of the most iconic “nerd hymnals” of the last decade second only to the lyricless Game of Thrones theme: The Misty Mountain Hop–errrr–the Misty Mountains Cold. Tolkien describes the song as “deep-throated singing of the dwarves in the deep places of their ancient homes;” which is hit perfectly on the head with Armitage’s low baritone voice. Not only is the scene and song moving, but it introduces us to a musical cue that will follow us throughout our journey. In the novel, it’s the song itself that awakens “The Took” inside Bilbo and his thirst for adventure, and personally I think it’s one of the most powerful moments in the Middle Earth Universe.

I Think I’m Quite Ready For Another Adventure.

So the adventure itself finally begins at the 43:30 mark—the length of an entire pilot episode—and ignoring the sluggish pacing, they have accomplished their goal of (re)introducing us back into the Middle Earth universe. They’ve painted thorough circumstances and laid out necessary plot points. They’ve given us good character repartee with Bilbo and Gandalf, and given some recognizable traits to our main dwarves (Thorin, Balin, Dwalin, Fili, Kili) and also introduced us to some important items like the key to Erebor and the Arkenstone.

All the while, Martin Freeman is just absolutely killing it as Bilbo. Our titular character is charming and affable and over-polite, but it’s all really only to mask his neurosis about being left the hell alone. He’s already a layered and conflicted character, and he hasn’t even stepped out his front door. If only this tale hadn’t taken so long to get going. I’m ready for a pee break already and we’re still in the Shire. Oh well, we’re finally ready for an adventu–

BUT WAIT. We haven’t had enough exposition, you say? Well how about another super melodramatic expository cut scene to introduce Azog—the big, uninteresting CGI baddy! Let it not be said that Jackson doesn’t “show” rather than “tell.” Actually he does both. Ad nauseum. So Bilbo, Fili, and Kili are told the backstory of Thorin’s relationship with Azog (because Fili and Kili don’t know their own family history?), who murdered his grandfather. This film is PLAGUED with so much exposition that it’s insulting to the words “adventure” and “journey.”

Yes, Radagast is important to Gandalf’s quest later, yes, Azog is important to Thorin’s character in a cliche sense, but piling it all on top of us right now is just too much. We already have the centralized evil of the plot: Smaug. Azog and the Necromancer are delightful appendices, but it’s all just more gravy slowing this film down. The only thing I can say that’s at all interesting is the fact that the orcs speak Black Speech, the language of Mordor. That’s an immersion we can well appreciate and a storytelling detail that’s well placed. In the first hour of the film though, all they’ve really managed to give us (after much delay) is an empathetic main character, a beautiful song, and exhausting CGI homework.

After the campfire and another unnecessary call to action (“There is one I could call king”), they set off for their journey to–

BUT WAIT. We abandon our quest and introduce a separate character, Radagast the Brown, doing a separate thing that deals with a separate evil. Oy. Couldn’t this have waited? Couldn’t we have eliminated the first Radagast scene? Couldn’t we have combined the Azog intro/campfire scene with roast mutton? Couldn’t the sound they heard, what they thought to have been orcs, have been the trolls? Balin says “Thorin has cause more than most to hate orcs,” and we let that just exist on its own for the audience to muse over and then the dwarves realize that the ponies have run off (they all run off in the next segment anyway)? Have the company send Fili, Kili, and Bilbo to go after the ponies and stumble into the troll’s campfire immediately. Done. I just shaved off like 20 extra minutes instead of sitting through another indulgent battle sequence starring characters we don’t care about yet. Get this story moving.

To give this context, my copy of The Hobbit has Roast Mutton on page 27. Chapter II. And when it finally arrives in the film, it’s fantastic. It’s funny and exciting and imaginative and things are, you know, happening to our cast of characters. Again they play it close to the original text and, to nobody’s surprise, it works very well. It’s almost like there’s a pattern here. Now, I’m not a Tolkien purist by any means because I can understand that a director doesn’t just want to be pigeon-holed into word-for-word interpretations whilst working in a completely different medium. But it’s no coincidence that when you stick close to material presented in a literary classic, it translates well.

When Jackson & Co. took creative liberties in the Rings trilogy, it was to condense and aid the main narrative that was already presented. In AUJ, wonderful Segments like “Roast Mutton,” “Riddles in the Dark,” and “A Short Rest,” segments that exhibit Jackson’s imaginative personality in his film-making, have to battle through all this extra weight that don’t add to Bilbo’s story. So instead of the source material in AUJ being augmented and elevated, these great segments stand out in spite of all the film’s meandering fluff.

“Why The Halfling?”…“The Who? Oh Yeah, Him!”

We arrive in Rivendell. It’s as beautiful as we remember it, and it doesn’t feel as jarring and strange when recreated the way the Shire felt. This is perhaps because we are now in the seperate narrative that we’ve been intending to tell, so it ought to feel different in the context of a company of dwarves. And if returning to the elven haven wasn’t enough nostalgia for you, then get a load of this reunion:

The decision is made to have the White Council while in Rivendell, because this film is just moving way too fast. While the White Council is important as far as Tolkien lore is concerned, and does make perfect sense to add into these films, giving us another planning scene with heavy exposition, even with Blanchett, Lee, and Weaving, is just exhausting at this point. In Tolkien’s appendices, we know that the White Council does occur in the time of The Hobbit, but it was meant to happen when Gandalf abandons the party at the edge of Mirkwood. It’s an obvious and interesting adventure for Mithrandir for certain, and one Tolkien intended on expanding on, but the White Council is yet another instance where the greater War of the Ring narrative swallows up poor Bilbo and his story.

Could we not have saved this scene for a later time? Could we maybe establish a trust between the elves and Gandalf that will lead to the White Council, but focus in on our main cast of characters instead? Again Jackson & Co are banking that you’ve already seen the previous installments of the films that actually bothered to engage in character building and action. Within the framework of the film, the story has now become about Gandalf plotting several different schemes in order to protect the realm from the threat of Sauron…but then who is this Bilbo fellow and why is he worth diddly?

The Bilbo we know and love is, has been, and always will be fascinated by elven culture. The dwarves in turn are filled with resentment, or at the very least prejudice towards this particular race. I would have loved to have seen a glimpse of those themes explored deeper than just “their food and music are both dry.” We need to know how Bilbo feels about certain things in order for us to see a deeper connections with the many dwarves we know barely anything about.

Instead, Bilbo takes a backseat to his own story, being referenced to or talked about, rather than experiencing and building relationships. Like in the scene between Galadriel and Gandalf, one of the more touching parts of the film, I couldn’t escape the feeling that the “why the halfling,” line was completely contrived. Bilbo and Galadriel never say a word to each other throughout the entire film, nor do Gandalf and Galadriel go over any plans about Bilbo’s burglar role…so why would she feel the need to ask Gandalf about the halfling? The obvious answer is to fit that lovely moment into the story…but unfortunately for us, the quote comes off as nothing more than a sentimental platitude as it’s drowned out by a lack of substance within the framing of the actual film.

What is Gandalf afraid of? What deeds has Bilbo done to have given Gandalf such swelling inspiration? What adversity has been thrown at them for the audience to relate to other than a “looming threat”? It boils down to this: unless you’ve seen Jackson’s previous Rings trilogy, these scenes carry very little weight.

What Are You Going To Do Now, Wizard?

When the company leaves Rivendell, we get a touching scene with Bilbo and Bofur and I’m wishing so badly that we had more scenes with our dwarves and less “Necromancer Hype.” There’s a wonderful folktale in here somewhere, I know there is! But then we make it to Goblin Town. This could have been a dark and daring escape sequence, heart-pounding and haunting. After all, they’ve decided to give their film a more ominous, gritty feel in order to liken it to the Ring’s trilogy.

Instead, they film the entire sequence behind a green screen and, rather than paralleling Bilbo’s terrifying encounter with Gollum—the highlight of the film—with a daring escape of their own, they juxtapose “Riddles in the Dark” with a mindless, tensionless CGI set piece. The goblins aren’t frightening, threatening, or interesting on any level. They move awkwardly and they feel weightless when they are beat around by the epic dwarf warriors in our suddenly impenetrable company.

Escape from Goblin Town, although fun to view in the same way a Michael Bay film is fun to view, has no risk and no reward. One frame shows a horde of goblins approaching, the next frame presents a solution. Repeat. While, again, it is sort of visually enjoyable to watch and imagine all the fun Jackson & Co had coming up with different ways to kill goblins, it falls flat when compared to Fellowship’s high-stakes, emotional escape through the mines. It comes off as insulting and indulgent when you trap your heroes just for a quick joke and a jab. It gets to the point where Dwalin says “There’s too many of them, we can’t fight them all,” I think to myself, really? You seem to be doing well thus far.

The Goblin Town segment would all be forgivable, excusable, downright enjoyable if it weren’t such a brazen betrayal of a direct quote from Gandalf not twenty minutes earlier in the film:

“True courage is about knowing not when to take a life, but when to spare one…”

It’s best summed up and articulated thusly:

“If Jackson meant for Gandalf’s comment to highlight Tolkien’s nonviolent ethic… the rest of his film undercuts it—and, indeed, almost parodies it. The scene where Bilbo spares Gollum in the movie comes immediately after an extended, jovially bloody battle between dwarves and goblins, larded with visual jokes involving decapitation, disembowelment, and baddies crushed by rolling rocks. The sequence is more like a bodycount video game than like anything in the sedate novel, where battles are confused and brief and frightening, rather than exuberant eye-candy ballet.”

So the choice to make Goblin Town a virtual theme park ride completely undercuts the value of Bilbo saving Gollum’s life, and renders Gandalf’s quote meaningless. All they had to do was take themselves seriously and that scene with Bilbo hopping over Gollum would have crushed me like…well like the Goblin King crushed the party of dwarves. Create a sense of peril, a sense of risk and remorse when you are in the throes of battle and then those “cool stunt moments” will actually pay off rather than be cause for eye-rolling. The dramatic moments with Bilbo are well produced and well acted, but ultimately betrayed by the need to indulge in violent spectacle.

By making the choice to have all CGI baddies chasing your CGI rendered heroes through a CGI backdrop, you quite literally dehumanize everything and enter the realm of farcical. You might as well have given Howard Shore a break on this and just dubbed Yakety Sax over the scene…oh wait…SOMEONE ALREADY DID THAT. Thanks for making my point for me, internet.

And it seems a waste of such a talent like Barry Humphries when you pretty much insert his character as a visual gag:

“What are you going to do now Wizard?” exclaims the Goblin King. *Gandalf rolls a nat. 20 and slices his stomach open easily.*

“He’s Been Lost Since He Left Home.” Yeah, Same…

Despite its bloated run time and contradicting themes, the film does end on a high note, managing to pull off an exciting and emotional battle sequence in “Out of the Frying Pan.” But it’s by the skin of its teeth. This story’s climax needed to be about Bilbo solving problems in an unconventional, hobbit-like way (*cough* like in the book *cough*) in order to prove his worth to the company. Instead, while we continue our theme of sacrificing subtlety in exchange for pageantry, Bilbo is given this grandiose moment of charging head on, taking on big bad Azog all by his lonesome, and being the hero that literally any of the other dwarves were capable of being because they charged in right after our suddenly fearless hobbit did.

There’s nothing wrong with having an arc where your character is a coward and he learns to be a brave warrior in the face of adversity, but that wasn’t the character you presented us with Bilbo. The real conflict lies between Bilbo and Thorin, and Thorin convincing himself that Bilbo is useless and slow and won’t serve a purpose in the company. And yes, we do get that moment at the end where Thorin accepts him into the company, and yes it is rewarding and emotional and well acted, but it’s slightly unsatisfying to have Bilbo earn his keep in such an un-hobbit-like way.

Like Butter Scraped Over Too Much Bread.

At this point, I’m aware that I’m being pretty muddled with my criticisms. But I think that speaks to the overall conflict surrounding these films. I want to love these films as a Tolkien fan, and there are things to love about AUJ in particular, but there are just too many glaring structural issues with these films for them to be considered well done interpretations of Tolkien.

There is also an entire army of stubborn Jackson fanatics that are downright delusional when it comes to The Hobbit Trilogy, and hail AUJ in particular as an undeniable triumph. I sometimes share that same sentiment when it comes to Jackson’s original Rings trilogy (Don’t you DARE try to point out the obvious and tell me Return of the King has too many endings, you monster!) because, well, they’re my favorite films. I love Peter Jackson. I owe him much, as we all do, when it comes to my love for fantasy and taste for modern cinema. But Jackson & Co made a mediocre film with AUJ, and it was overall met with (deserved) middling results. Much of it was out of their hands, yes, but so much of these bad film making decisions could have been avoided by taking a more minimalist approach and just focusing on the story Tolkien was trying to tell.

Looking back on this Trilogy, the biggest compliment you can give The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey is that when compared to the next two installments, it isn’t that terrible. It’s a film that can be fun at times, but ultimately gets crushed under the needless attempt to be compared to its predecessors. Themes like “home” and “fitting in” and “compassion over violence” are touched upon but never explored more than a convenient monologue to transition into a new segment.

For lighter fans of Tolkien, this film is a fun romp that will at times put a smile on your face. For obsessive Tolkien buffs, it’s a grave insult. But this film made a ton of money—like, a whole troll chest full of it—and as far as Amazon making more Tolkien content, I’m a bit worried they’ll put profit before all else. See because this movie, while thematically flawed, and weighed down with gratuitous exposition, does still possess the same entertainment factor found in many of its kind of pop-culture blockbusters, and so people indulge, enjoy, and defend its right to take the paperback it claims to base itself upon and dial it up to 11.

But strap in, because AUJ only covers chapters 1-7 in the book.

To be continued in part II…