Content warning: article contains discussion of child abuse; Spoiler warning for all three seasons of Stranger Things

Netflix released the third season of its nostalgic-based darling, Stranger Things, to resounding acclaim last month. Judging by their heightened visuals this season, the Duffer brothers have grown more assured in their cinematographic skills. It was like going through a mild manic high for eight-plus hours: the neon-tastic color scheme energized me like no other piece of media has in recent memory. And while the colors had my brain spinning, it was the characters who had my heart swelling.

Notably, the show’s arguable protagonist, fourteen-year-old Jane ‘El’ Hopper, underwent a feminist transformation this season — one reflective of an abuse victim breaking down the internalized messages of her abusers.

For reference, this article will be the first in a two-parter. I will explore El’s character arc early this season by contextualizing it within her whole storyline. The second article will go deeper into visuals that comprise the latter half of season three, and as a teaser, these visuals include a Wonder Woman reference, a scene that recalls book Sansa from A Song of Ice and Fire, and an image that evokes a conspiracy from modern art history.

(As an aside, for the rest of the article I will refrain from using the term “victim” in reference to abuse due to its associations with shame and stigmatization. Instead I will use the term “target,” as it implies action that a perpetrator takes against someone else. The term was popularized by published counselor Kris Godinez.)

A Different Shape

In a 2009 interview, SFF author Lois McMaster Bujold discussed the Campbellian story structure, specifically, how the traditional Hero’s Journey fails to align with women’s coming of age historically and culturally:

The journey into maturity […] has an entirely different structure for women than for men, starting from the fact that while the male goes out into the world and returns to his starting point to take over the role of his father, the successful female (in exogamous cultures, which most are) goes out and keeps on going, never to return. The Hero’s Journey is just the wrong shape for the Heroine.

While the Heroine’s Journey does not have to apply exclusively to female characters, the narrative structure tends to favor them. (This literary model does not, as far as I have seen, go into trans and nonbinary characters, but that is a discussion for another day.) The model’s progenitor, Maureen Murdock, designed it as a feminist counterpoint in literature. The protagonist must rediscover and reclaim the disparaged feminine and her heritage as a woman. The Heroine’s Journey is also cyclical in nature and thus offers a more complex space to explore a character’s psychology.

Women-centric stories circle in on themselves through numerous births, deaths, and rebirths. They are the narrative ouroboros, if you will.

Recalling Bujold’s statement, as well as the model’s original purpose, gave me an anchor for understanding El’s arc in the show. Like many girls and women, fictional or not, many of her social influences derive from the women around her. These views become more complex and feminist as she moves away from men’s influences. The most influential women in El’s life are her birth mother Terry Ives, her foster sister from Hawkins Lab Kali Prasad, and her best friend Max Mayfield.

Though Joyce Byers is also important to El, the show has barely scratched the surface of their relationship, which I hope we see more of in season 4. It’s what we, Winona Ryder, and Millie Bobby Brown deserve.

Wounded Daughter

To say the least, El is a survivor. She was abducted from her birth mother because of psionic abilities that stemmed from Terry’s government-sanctioned use of experimental drugs. El then endured twelve years of physical, psychological, and medical abuse at the hands of Dr. Martin Brenner and his staff.

Brenner had “raised” her to see him as “Papa” and trained her to use her powers as a weapon against the Russians. He objectified her as a tool for militarism, forcing her to occupy the masculine-coded space of violence. He also denied El her femininity in general: her head was shaved against her will and she was forced to wear dehumanizing hospital gowns. Their dynamic mirrors real-life abusive father-daughter relationships as these perpetrators offer “love” under conditional terms. For example, he coerced her into using her powers on a cat for an experiment, and when she stopped, he tried locking her in a cell as punishment.

Abusers take advantage of a target’s compassion, using it as a source of manipulation and then twisting it, attempting to make the target more like them. Such interpersonal paternalism affects girls more than boys, as society condones hyper-controlling fathers who keep their daughters safe from the “dangers” of the outside world. Consequently, El’s gender and gender presentation are inextricably linked to her abuse.

As outlined in the 2015 reprint of her seminal book, Trauma and Recovery, psychiatrist Judith Herman describes the recovery process from trauma:

The central task of the first stage is the establishment of safety. The central task of the second stage is remembrance and mourning. The central task of the third stage is reconnection with ordinary life. (p. 155)

Herman also stresses that with stage three comes a sense of purpose in fighting against the injustice of the trauma, to help other targets. This often comes in the form of activism and community serviceship.

Each of the show’s current seasons follows this structure in relation to El’s character arc. Throughout season one, she alternates between living on the run and living in hiding, always glancing over her shoulder. Her life is finally stabilized when she and her adoptive father, Hopper, find each other in the interim between seasons one and two. After almost a year in his care, she then seeks out her birth mother. By finding Terry and then her sister, El begins the grieving process, sorting through old memories made anew. Pointedly, in the stages focused on growth and renewal, El forms her most emotionally resonant relationships with other women.

Wayfaring Sister

Resisting Brenner’s influence while living in opposition to his worldview forms the core of El’s philosophy regarding violence. Season two plants the seeds through her mother and her sister, in episodes “Chapter Five: Dig Dug” and “Chapter Seven: The Lost Sister” respectively. The two women form a triangle of resistance with El as the link. Terry fought Brenner’s institution legally and then physically in an attempt to rescue her daughter. Kali wages a private war against Hawkins Lab, hunting down her abusers and executing them. She goes so far as to train El to channel her anger into power so as to prevent her wounds from “festering.”

Though she comes from a place of violence, Kali ultimately focuses on injustices and society’s marginalization of others, having brought together and helped outcasts from various societal levels. Kali using the word “fester” to refer to her and El’s complex pain and trauma reflects her focus on healing through action, which is itself a political and feminist act because it calls for a change in the system. Her word choice makes clear that traumatic stress is an illness in need of treatment.

That being said, though El accepted having to kill out of self-defense, the sisters differ in their take on mercy. Notably, El spares one of their abusers for the sake of his daughters. She needed Kali’s help to address her wound more constructively, yet she draws from her mother’s compassion, as Terry also had directed El to Kali in the first place so the girls could help one another.

In general, Terry and Kali’s motivations stand as the pillars of El’s developing worldview: one fought from a place of love, the other from a place of rage. They come together when El destroys the Mind Flayer in the season finale — her power fueled by memories of mistreatment and driven by the desire to protect her friends.

Materials of a Girl

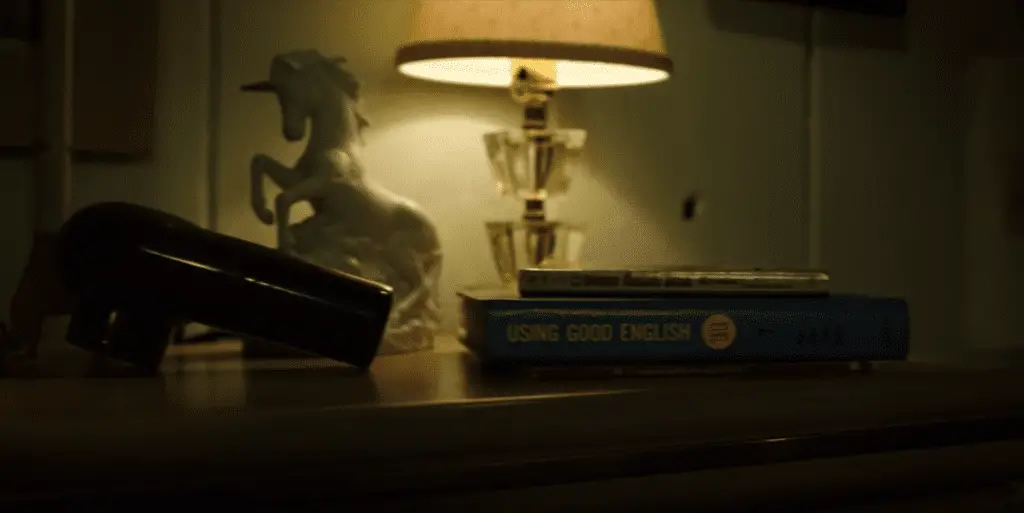

With this foundation in place, we meet an El in recovery in the current season. Some poignant details signal El’s growth over the season two-three time jump, and they appear in her first scene from “Chapter One: Suzie, Do You Copy?”. As the camera pans through her bedroom, which has been decorated with signs of life, it passes over a language book called Using Good English.

Throughout the first two seasons El had struggled with basic verbalization due to Brenner’s abuse, including forced isolation from birth, and due to trauma literally silencing her. For over a decade, it’s been established that trauma affects the part of the brain associated with speech, with effects reminiscent of symptoms seen in strokes (see Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score, p. 43 for example). Now though, El is able to communicate her wants and needs and to socialize, making connections and bonds on her own terms. The props department hit this home as the book rests near a hair dryer and a unicorn figure, objects associated with femininity and youth.

Throughout season one, El often looked at her reflection and mourned her appearance, but she took back her body and her gender. That reclamation is best captured in the bracelet she wears on her left wrist, which partially obscures the numbered tattoo Brenner had branded her with. She lives with her abuse — always as a part of her — but she puts it aside so she can be her own person.

Indeed, her arc early in season three focuses on her establishing her identity apart from her father and her partner. By this point, her and Hopper’s dynamic had evolved into the traditional exasperated father and teen-aged daughter trope as she pursues a relationship with Mike Wheeler. Those relationships quickly become strained due to their overprotectiveness, emotional hang-ups, and poor communication skills. Feeling neglected by Mike, El reaches out to the only other girl in their friend group, headstrong Max. From there, a sisterhood blossoms.

More to Life

Recalling Bujold’s comments on community, as El left Brenner’s culture, she now has left Hopper and Mike’s spheres. In “Chapter Two: The Mall Rats,” Max furthers El’s education into empowerment, explaining gender politics between teenagers. She uses her own relationship as an example, declaring several times that, “There’s more to life than stupid boys,” and also instructs El to dump Mike should he not improve. Max has no qualms calling out Mike for his “garbage” behavior to El, and this reveals an interesting layer to her character.

Like El, Max was a target of childhood abuse. She had also been a witness to domestic violence, having been targeted by her toxically masculine stepbrother and watched her mother been verbally abused (at least) by her stepfather. Her advice to El indicates that she has done private emotional work to detach herself from both a dangerously sexist environment and from any of her stepbrother and stepfather’s influence.

In glorious fashion, the Duffers then have us follow the girls as they explore the new mall. Max has taken it upon herself to help El open up as a person. In a poignant scene, she even encourages El to experiment with fashion as a form of self-expression:

Max: Do you like that?

El: How do I know… what I like?

Max: You just try things on. Until you find something that feels like you.

El: Like me?

Max: Yeah. Not Hopper. Not Mike. You.

The camera lingers over her face as she gazes at an outfit, the close-up making it clear to the audience that this is about El’s identity. Her first experiments with femininity began in season one when she disguised herself with Nancy’s old dress and wig. It was only a first step, one less steady and understood. In season two, she then experimented with all-black and punkish make-up, following Kali’s lead in style. Her friendship with Max is her first relationship with another girl that’s on relatively equal terms. Her new outfit stands in contrast to Max’s in terms of style and color. Like a snake sheds its skin, El sheds her father’s hand-me-down flannel and jeans, embracing bolder colors and patterns. She looks to Max for guidance, yet she is more assured in herself to go in her own direction, rather than emulate.

Throughout their shopping montage, Max and El also hold hands or link arms several times, another example of El’s growing bodily autonomy and reclaimed life. We don’t see healthy, platonically affectionate relationships between teen-aged girls enough in our media. In our touch-starved culture, it is easy to forget the value in friendships and how oversexualized basic physical contact has become. Fittingly, by the end of the trip, El discovers that she is not satisfied with Mike as her sole anchor, and that she never was. Though she and Mike reconcile later in the season, her sense of self has grown more balanced. She can have a father and a partner’s love while still being her own person. Rather than reinforcing El’s upbringing that she should acquiesce to men’s wants and needs, whether utilitarian or emotional, Max shows her a world outside the princess’s tower.

And though she will always have scars from that first tower, El’s journey consists of multiple restarts. And with every restart, she moves further away from “Papa” and towards understanding herself on her own terms.

Images courtesy of Netflix