In the latest Holmesian adaptation, Sherlock once again has a genius little sister, and just like with the BBC show, viewers should be gearing up for disappointment. Yesterday Netflix dropped a trailer for the new Enola Holmes movie, and as a fan of the original book series, I have some words. The Fandomentals built this site based on unabashed book snobbery, and now it’s my turn to pour the salt.

Nancy Springer published a five-book series from 2006 to 2010 that chronicled the adventures of Enola Holmes, much younger sister to the famed detective. The movie will be adapting book one, The Case of the Missing Marquess, which centers around Enola running away after her mother disappears. Raised by a single mother and proto-feminist, Enola fails at the rigidly prescribed womanhood that Mycroft Holmes valorizes. It’s Mycroft wanting to send her to boarding school — and the literal dangers of being forced into a corset — that prompt her to run away in the first place. The series follows Enola as she settles in London, outwitting Sherlock, and solving mysteries. Her relationship to womanhood and how that relates to her absent mother go to the core of Springer’s story.

Back in 2018, it was announced that Millie Bobby Brown would be starring as the titular Enola Holmes. I had high hopes for this casting choice for several reasons. For starters, Brown possesses the range to reveal the layers in Enola’s character — the flash of her wit and the warmth of her compassion against her insecurities, her grief. The age fits. (A teenager playing a teenaged character, what a concept!) Brown and her sister also came onto the project as co-producers, and it’s a good sign when women’s voices are represented behind-the-scenes. But my hopes started to dwindle when I saw that men wrote and directed without accredited input from Springer.

The trailer bleeds the kind of marketable Girl Power (™) that espouses the Not Like Other Girls character we’ve bemoaned for years. The Strong Female Character that’s often a product of men co-opting stories about women and shoving them through a masculine concept of agency.

The trailer starts off with Brown as Enola informing viewers of her situation. Positioning Enola as a fourth-wall-breaking narrator is intriguing and could have been a clever tool to bridge the gap between book and film if it properly adapted Enola’s narration style. Written in first-person, book!Enola narrates everything and her secrecy means she remains an internal character to a large degree. That in mind, the movie advertises itself as an upbeat adventure film with the auditory and visual hallmarks of a fun teen flick. Those films aren’t lesser for their cheeriness or plucky heroines — spunky female characters can be fun. But the overall feel of the film clashes with the books’ tone and themes.

The books are chock-full of detailed descriptions about the London cityscape, littered with obscure references to Victorian culture that led me to keeping a dictionary open on my phone. Though Springer does not get into graphic detail about the horrors of Victorian society, she neither shies away from such topics. Enola consciously navigates a misogynistic culture, and her mysteries often deal with the intersections of class and gender. Springer also weaves a relatable tension for Enola because as a character, she struggles to repress her feelings of inadequacy as a young woman and feeling abandoned by her mother. Readers come away uplifted because they have experienced the gauntlet of girlhood through Enola’s eyes, the happy endings made sweeter by the bitterness. In many ways, the first Enola book is also not driven by the titular mystery but sheer survival, as our heroine grapples with her newfound independence and isolation.

Two egregious examples in the trailer reveal the filmmakers’ blundering of the source material. One: Enola Holmes seemingly dressing up and posing as a boy. We see her take clothes from Sherlock’s trunk and then running around the English countryside in said clothes. That directly contradicts a trope that Springer sought to subvert in the first book. In The Case of the Missing Marquess Enola makes the conscious choice to not disguise herself as a boy because she knows Sherlock would expect that and because she does not want to give up her version of feminineness. Two: the trailer has a voiceover that could have been pulled from an earlier draft of a Game of Thrones script. Enola boasts, “Unlike most well-bred ladies, I was never taught to embroider. I was taught to watch. And listen. I was taught to fight.” Yes, the filmmakers shoved Arya Stark into a fancy dress and had her disparage the very skill needed to make said dress. As well as added some action-heavy fight scenes because Girl Power (™).

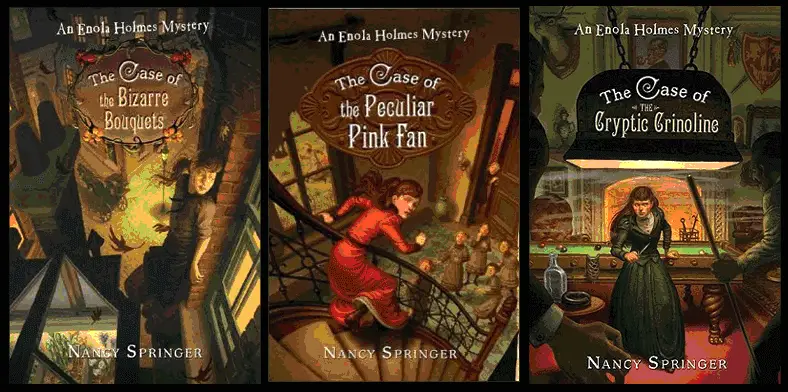

In the books, there’s even a recurring theme that Sherlock’s misogyny and his disdain for women’s interests lead him to missing clues. Three of the book titles refer specifically to items in women’s culture — flower language and women’s clothing — which Sherlock would overlook. But Enola doesn’t.

Seriously, you know that a man wrote this script because ‘women weren’t taught to listen’. Excuse me? As if we haven’t had more than three millennia of being told to shut up, sit in the corner, and let the men do the talking?

I bet it will be fun watching Millie Bobby Brown sass sexist men and walk away from an explosion with that stereotypical badass expression. But that story isn’t Enola Holmes, and I doubt it’s why so many readers remember that book series fondly. The Enola Holmes series focused on a girl coming of age while learning to grapple with her contradictions and discovering her passions in life. Enola Holmes actually being like the other girls inspires those girls that they can be as spectacular as her.