As you may know, many of my articles here consists of me complaining about things that vex me. This one will be a little bit different. Today, I will complain about people who complain about things. Specifically, the tendency I’ve noticed for unhappy fans to act like we know better. Like if we were in charge, it’d all be so simple. Such fan reactions ignore issues of resources, time, executive decisions, and so many other factors we don’t know about.

Note that I say “we.” I have done this, many times. I will probably do it again in the future. Still, I’ve become more aware of it and I feel as though it’s becoming more rampant. Whether or not it is becoming more rampant and although it is a controversial topic, I still feel like it merits attention.

Many of us who read and write for this portal are familiar with “fixing X,” or “how I’d write Y,” and such. Most of the time, it’s harmless fun. But as with all such things, it can cross into harmful territory. I’m going to discuss some examples I’m familiar with, though of course there’s more. Steven Universe, for example, seems to have a legion of people claiming they’d do a better job writing it than the actual Crewniverse, but this is not a pit I’m willing to descend into.

Let’s start with a different example that is very familiar to those of us here: Legend of Korra. Many of us love it, some have a more complicated relationship. Regardless, in my interaction with the fandom over the years I have seen many “what ifs.” Recently, in fact, I saw such a post. I gave it a read and mostly moved on with my day, but it got me thinking. I started looking back other such takes I had seen and others I had written myself. My experience concerned itself mostly with the first season, which seems to draw such “what ifs” more than the other seasons.

The first conclusion I drew was that none of the rewrites mentioned would fit into less than twenty episodes. Which, as we know, none of the show’s seasons got. And they were, in all likelihood, never going to get. We can rail against such unfairness and point out the likely racial and gender-related reasons why it happened, but that’s what showrunners have to work with. As well as many other reasons that we will simply never know anything about.

Beyond the matter of time constraints, when I see people “fix” television shows, not just Korra, I just keep seeing plots that would change the whole story or be far too mature for the intended audience. Or, very commonly, simply not be suitable for television. A medium has its demands, and some things just won’t fit. One can argue that the first season’s plot was just too ambitious to ever work in this medium and this writing crew. That may very well be true.

Does knowing such constraints or complications exist mean that we shouldn’t criticize shows or point out how something could have and should have been done better? Hardly. But it’s a fine line to tread. I am a staunch opponent of not doing creators’ work for them and making things up to explain holes in the story. But at times, playing too much ‘script doctor’ becomes the opposite extreme of that.

I feel like the underlying sentiment behind many such ideas is a wistful desire for more. It’s comforting to believe that our beloved but flawed show could have been great if only something happened. It’s more difficult to accept that what we got may have been the best we were ever going to get.

A lot of this is just for fun, of course. There’s no harm in letting our imaginations run wild. But sometimes I feel like it moves beyond that and becomes mean-spirited. I saw it from the other side of the equation, as it were, after the series ended. A number of people were unhappy with the finale, particularly Korra’s relationship status. What followed were many “fix-it” fics and proclamations of how the writers don’t own the characters because they ‘didn’t treat them right.’

I’m trying to keep my personal opinion to myself here, but this feels like a similar, if perhaps more emotional, reaction to playing script doctor. People feel that a show they loved, or could have loved, let them down in some way. So rather than simply move past their anger or disappointment, they begin searching for reasons it could have been good. But it wasn’t, such reactions claim, either because the writers were incompetent or actively took it from us.

In order to really delve into how such behavior is more common, though, we need to leave television shows behind and enter the land of video games. Here, the concentration of people who think they know how to make the best game there ever was increases considerably.

The games I’m most familiar with this happening are Dragon Age and Mass Effect, two flagship franchises of a company that some think isn’t long for this world. With Dragon Age, it’s similar situation to Legend of Korra and many other television shows in many ways. Which is to say, people simply don’t account for budget, time, effort, and technical limitations. This works itself out in in Dragon Age by demanding more race-specific and class-specific content.

This isn’t to say that the world reacting to us differently depending on our character’s race and class is a bad thing. But there’s a reason games with multiple choices in this regard only have occasional interactions. The most I’ve seen was perhaps in Pillars of Eternity: Deadfire, which has the advantage of having a substantially simpler style. And some of them even applied to my human fighter/rogue, which is a plus, even if most of them were for godlike. The reason such interactions are rare is of course that every such divergence costs time and effort. The more we diverge before returning to the main conversation/interaction tree, the more expensive it’s going to be to make.

To be fair, the Dragon Age series set a precedent with its very first installment, which has several eponymous “origins.” Our hero’s story starts in a different place based on their race and station in life. Which is great, but once the origin story is over, most of it disappears – though it does sometimes come back in big ways, such as when a human noble can marry Alistair and become Queen, but a non-human or human mage Warden cannot.

I suppose when you put them next to each other, Origins might have more race-specific content than Inquisition. I’m not sure. I’ve heard rumors that the latter game may have been planned to be human-only, like Dragon Age 2. I don’t know how true it is, but the game does rather center on the human Chantry, whereas Origins had the Grey Wardens as a deliberately “unifying” element. Whoever you’d been before the joining, you were a Grey Warden from there on.

One way or the other, while it’s perhaps unfortunate that our race and class don’t matter as much as they could, it probably isn’t because the writers just didn’t feel like it or had it out for one particular option. Nor would it be easy to have done it otherwise. Inquisition is a much bigger game, and unlike Origins, it involves a fully voiced and animated protagonist.

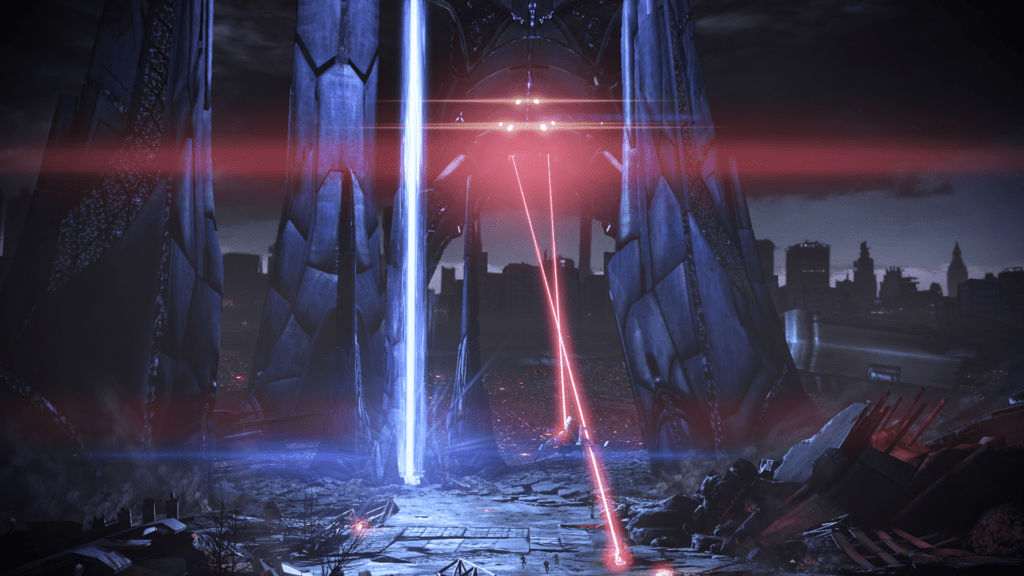

The other franchise where I saw this phenomenon balloon to mountainous proportions was Mass Effect. Now, let’s not mince words here. The endings to Mass Effect 3 were bad. Who was to blame and how much of it was inevitable is a discussion that people have had ad nauseam. What I’m talking about is the fan reaction here, particularly when Andromeda came out.

What was it that fans would rather have happened? Well… I’m honestly not sure, to this day. A re-release of Mass Effect 3, only with a proper ending? A Mass Effect 4 to replace it? I once had a conversation with someone who seemed to honestly believe they should have canonized the “Indoctrination theory.”

For those unaware, it’s a very peculiar fan theory, according to which everything after the final charge towards the Citadel beam is a hallucination due to Shepard succumbing to Reaper indoctrination. But the person I spoke to claimed it could have and should have been done in game.

“They should have” and “they could have” keeps coming up here. Once again, I’m not going to begrudge people for being angry about the endings. But this is a different kind of feeling. It’s more personal. It’s not “this game ended poorly,” but rather “this game could have ended great, but it was taken from us.” Alongside spinning theories about how easy it could have been to make it great, that kind of thinking turns incompetence into malice.

Tying it to my Legend of Korra examples, I think that, strength of emotion aside, it’s a similar reaction. A series we loved turned out disappointing, so we try to imagine what could have been, which some turn into being angry about how the authors denied us that. Because it’s so obvious, to us, that it could be great. We create an idealized image and cling to it.

I’ve talked about story before, but it applies to gameplay as well. If you’ve participated in any online multiplayer game, you’ve no doubt noticed how after every patch there’s a deluge of opinions by people who are apparently experts at game design and competitive balance. They clearly know more about the people working on those games, anyway.

I feel like there’s a personal element here as well. Many such complaints focus on how a given player’s favorite character or class is clearly being unfairly treated. Players tend to focus on a small corner of gameplay that concerns them, personally, and miss the big picture.

Every change made to a game causes ripples. Balancing a competitive experience is an incredibly delicate affair, one that we can’t quite properly judge from our perspective as players. Even if developers make mistakes or are bad at their jobs… well, it is a job.

Sometimes, though, it’s the big picture that’s the problem. Here is where I need to loop back to resources. I mentioned, while discussing television shows, that people have grand ideas that don’t really fit into realistic budgets and timeframes. Well, it happens in games as well. I once witnessed a rather… interesting perspective where someone insisted that Pillars of Eternity: Deadfire should adopt the D&D model of attributes. According to them, it would be easy to make different attributes useful to every class, which is a big problem with D&D.

The solution? Weave them into dialogue, so that having low attributes penalizes you and takes away options. Easy-peasy, really. Just a massive amount of work for writers and programmers that would likely just result in raising the minimum attributes a bit. If having a strength of 5 makes us fall over when trying to open a door, just leave it at 6 if our class doesn’t demand it.

Here’s the brutal truth of it – ideas are cheap. It’s easy for us to imagine our ideal show or game, but an idea only has merit when it’s been tested, rejected, reworked, tested again, and so on. And even then it might turn out it’s good, but simply not very realistic. Whereas we often lose ourselves in our great concepts without ever having to put them to the merciless grindstone of reality. There’s an element of nostalgia, too. We want a game that matches our idealized memories of the games we used to play.

To bring it all back, I want to stress once again that I’m not unilaterally defending creators. Sometimes, frequently even, they do make mistakes. They bungle their own plots or make mistakes in execution. Even if they don’t, creative works fall victim to bad management. All of it deserves pointing out, criticism, and honest, sometimes harsh, discussion.

It’s a fine line to walk, to reiterate. Providing alternatives and suggesting what someone could do better is the cornerstone of constructive criticism, rather than complaining. But sometimes there’s only so much criticism you can provide without knowledge of the subject. And consuming media doesn’t necessarily make us experts on it. I think the increasing engagement between creators and audience makes some of us lose sight of that sometimes.