I have seen Monty Python and the Holy Grail so many times it has been practically woven into my DNA. Yet, each time I am surprised by something new, I notice some obscure joke I had previously missed because of my ignorance. Watching Holy Grail is like having an old friend over for dinner in many ways.

Directed by one of the Pythons, Terry Jones, with Terry Gilliam in charge of the animated portions, Holy Grail is a parody of Arthurian legends both in film and on principle. Unlike their first film, And Now for Something Completely Different, Holy Grail is a movie, sort of. Written by the whole troupe, including Jones, Gilliam, Michael Palin, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman, and John Cleese, the movie has enough story to get us from one gag to the next. The extra in the background with the shaving cream beard is a long-standing favorite of mine.

The idea of Holy Grail as a holiday movie may be stretching it a bit thin to some. But I think more than anything, I’ve reviewed the most Holiday movie. So many movies about the Holidays tend to peddle the message of “embrace tradition and reject modernity.” Holy Grail is a movie that triumphantly declares rejecting tradition and embracing modernity. It scoffs at the idea of tradition for tradition’s sake and ruthlessly skewers everything and everyone.

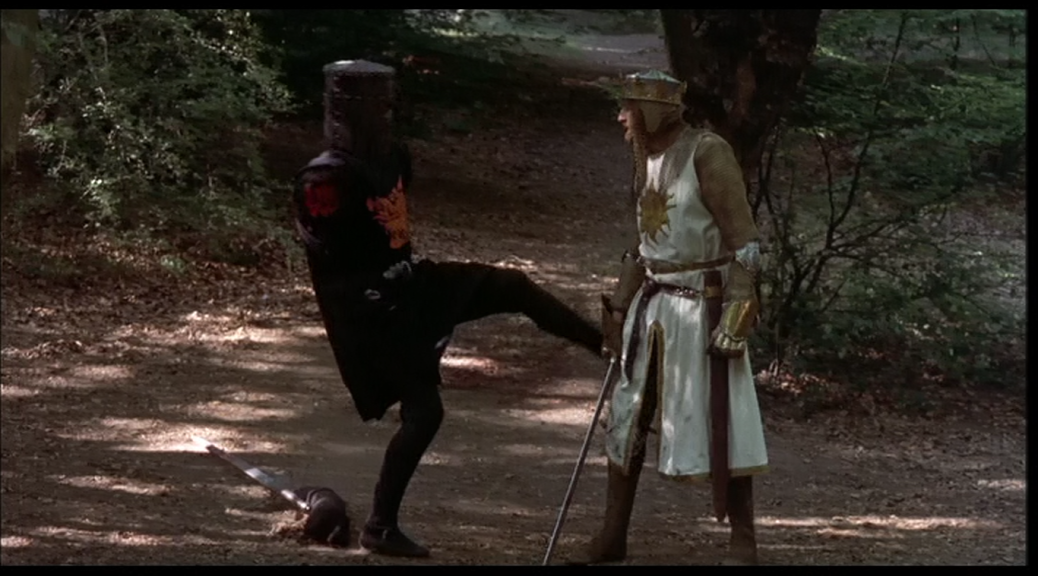

Not to mention, I’d say a lot of the conversations in Holy Grail feel presciently like present-day online and real-life political discourse. “Do you see the violence inherent in the system,” is something I imagine is screamed at Holiday dinners across the country and is something I have seen across all social media. The Black Knight perfectly represents that conservative relative who refuses to admit that the facts have disproved his backward belief, “Both your arms are gone.” “No they’re not. It’s just a flesh wound.”

Even the “Bring out your dead” scene has morbid undertones, seeing as we lived through a modern plague of our own. Especially in the callousness shown regarding the mounting corpses as just another Tuesday. The line about how Arthur (Graham Chapman) must be the king “because he hasn’t got shit all over him” rings as true today as it did then about the class divides between the working class and everyone else.

The most potent is the “burn the witch scene,” in which an angry mob brings a woman dressed as a witch, Miss Islington (Connie Booth). With a fake carrot nose and a pointy hat, she certainly fits the bill, and the crowd wants to see her burn. Except Sir Belvedere the Wise (Jones) isn’t that wise as he spewed a truckload of gibberish that has the crowd lost but eager as it seems to agree with them. Even Arthur finds him knowledgeable.

It’s all silly, but there’s a genuine attempt to show how mob anger and pseudo-intellectuals often go hand in hand and how the rich and powerful can raise them to prominence by giving them a platform. The argument is so convincing that it even convinces poor Miss Inslignton. Once it’s revealed that she’s a witch because she weighs the same as a duck, she says, “That’s a fair cop.” But it wasn’t until this re-watch that I noticed that after they took her away, we saw the scales weren’t balanced, and the test was rigged. Meaning Islington’s comment is less a confession and more a resignation to a patriarchal reality.

The knights, Sir Lancelot the Brave (Cleese), Sir Robin-the not-so-Brave (Idle), Sir Belvedere the Wise (Jones), and Sir Galahad the Pure (Palin) are hardly the heroes we’ve read about. They are less noble and more violent, horny, cowardly, and yet more human than the legends that have survived the centuries. Indeed, the actual tales of King Arthur contain all these things, but popular culture, as with most traditions, tries to sanitize them and sand off the rough edges. Holy Grail instead sands off the nobleness and heroics and presents us with a cadre of goofs and imbeciles on the quest for the Holy Grail, heedless to the chaos and destruction they leave behind.

The look of Holy Grail is part of its charm. Shot by Terry Bedford, the film embraces a kind of cheap, tacky ugliness that makes everything else seem sensical—using two halves of coconut shells instead of a horse, turning the picturesque Scottish countryside into a dreary, damp landscape of the Middle Ages. You can see the filth and feel the humidity. There’s a tactile feel to Holy Grail that belies its googly-eyed, playful nature. Bedford and Jones craft a world barely civilized and let loose a horde of jokes, satire, and gags that stand the test of time.

The aesthetic of Holy Grail helps with the absurdity of the film. In a way, it makes the film feel relatable. The scene with the King repeating his simple orders to his two guards to “Stay here and don’t let him out of your sight” resembles conversations I’ve had with co-workers so much that it’s almost triggering.

Gilliam’s animations provide imagery ripped from an artist’s id, surrealist and Dali-esque; they are the hammer to the rest of Holy Grail’s nail. The flippant and absurd animation makes the rest of the movie hit harder, as the live-action stuff seems comparatively weirdly realistic. Gilliam’s colorful and bizarre artwork clashes with the earthy, mud- and shit-encrusted reality of Arthur and his knights of the Round Table. They are the tales we tell ourselves to make the reality seem less grim and more bearable.

When you get right down to it, many traditions, Holiday ones especially, or ones borne from crass commercialism, are seen through nostalgia and absurd nonsense. The Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch and its instructions feel eerily like putting together a DIY Christmas present. The directions are seemingly designed to make us feel like idiots but also realize that we may not be as bright as we think.

But honestly, what’s more heartwarming than seeing a King arrested at the end of a movie? Happy Holidays!

Images courtesy of EMI Films

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!