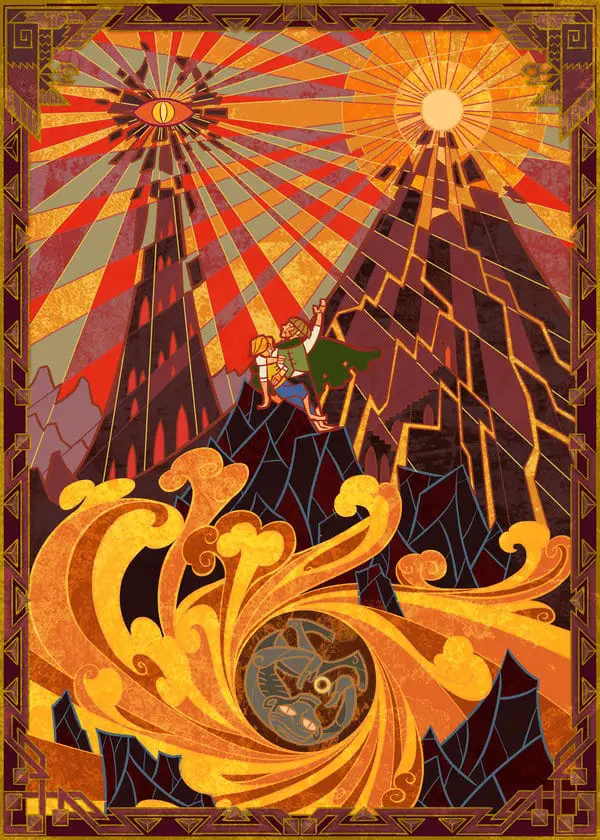

I am glad that all of you are joining me here today, here at the end of all things (except for the several months and six chapters that we have left to go). But we’ve certainly reached the end of a line if not the line: the Ring is destroyed, Barad-dûr and the Nazgûl have sputtered out, and The Lord of the Rings has made one of the most unique and interesting narrative choices in its whole run.

That Frodo is unable to destroy the Ring when he reaches the Cracks of Doom is both inevitable and devastating. After all, poor Frodo couldn’t even toss the Ring into the fire at Bag End! It would undercut the weight of much of Return of the King and The Two Towers if Frodo were simply able—even after an internal debate— to toss the Ring away. Yet the fact that he cannot, and does not, makes The Lord of the Rings a different sort of story than the classical hero’s journey template into which it is often uncomfortably shoved. Instead, “Mount Doom” is concerned with suffering and its relationship to empathy, the reach of moral limitations, and what happens when someone is forced to surpass them. I don’t think it’s accidental that it’s one of Tolkien’s more unusual moments in his story, and also one of his most intensely Catholic.

Stone and Steel

While you can see “Mount Doom” as the deconstruction of a hero’s journey through Frodo’s arc, there’s also a parallel apotheosis through Sam. Sam has a classic journey: called into a big world beyond his purview and able to overcome the final challenge to his will to stare death in the face and carry Frodo up the mountain. He later will return home, marry his sweetheart, and be MAYOR FOR LIFE. This is something, in a very traditional fashion, that Sam “achieves:” he “wins” through force of his sheer indomitability. Sam’s victory here is not so much rooted in the fact that he maintained hope against all odds—though he does that for quite a long time—but in the fact that when he loses hope, he doesn’t fall into despair. In this sense, he forms a nice thematic bridge to Denethor and Pippin in Book V.

This is an old-hat theme for Tolkien at this point, but it’s given extra weight because of the sheer devastation that surrounds Sam. He considers in a casual way that without the fortification of the lembas bread he and Frodo would “long ago have lain down to die.” The force of Sauron’s power as they delve deeper into Mordor feels like “the oncoming of a wall of night at the last end of the world.” He becomes aware for the first time that even if they do reach Mount Doom and destroy the Ring, “they would come to an end, alone, houseless, foodless, in the midst of a terrible desert. There could be no return.” And aside from all of this, Sam’s closest companion and master is being eradicated, both mentally and physically. He stops speaking almost entirely over the course of the chapter, and when Sam lifts him he is surprised to find Frodo weighing no more than a “hobbit-child.” And yet:

Even as hope died in Sam, or seemed to die, it was turned to a new strength. Sam’s plain hobbit face grew stern, almost grim, as the will hardened in him, and he felt as through all his limbs a thrill, as if he was turning into some creature of stone and steel that neither despair nor weariness nor endless barren miles could subdue.

It is understandable why Sam is most people’s favorite character in The Lord of the Rings. Despite his limitations he’s loyal and kind. And he’s the aspirational vision of an unbreakable will: that no matter how bad things get, he can keep putting one foot in front of the other in order to save the word. Frodo wouldn’t have gotten very far without his Sam indeed.

Suffering and Empathy

But that isn’t the only story at play here, and it is interesting how closely Tolkien mirrors Frodo and Sam’s opposing journeys. Sam’s ultimate triumph comes on the brink on Frodo’s “failure.” And as Frodo’s experience with the Ring and its accompanying suffering finally strips him of pity, Sam’s own (short) experience grants it to him. These intersecting journeys serve to highlight a much-observed fact about Tolkien’s climax. It is centered on the role of pity and empathy and suffering, of mercy and grace, as the ultimate narrative power (just as Book V prioritized hope and healing over military prowess).

Frodo’s character has always been rooted in empathy, to a point that he is almost idealized (or as Tolkien says, “saintly”). This was only exacerbated by his role as Ring-bearer: his own experiences let him see himself in Gollum, giving the poor creature multiple chances at redemption, beyond the dictates of prudence. Frodo is kind down to his bones. But as the Ring continues to chip away at his sense of self, and as he moves closer to its source of power in Sammath Naur, what had once been a source of empathy and pity simply starts to consume Frodo. He freely admits to Sam that there is no real way in which he could give up the Ring.

And when we as readers get one more glimpse of Frodo in the context of his most dedicated and persistent empathy—in his relationship with Gollum—we see that both ends of the relationship have been utterly decimated by the Ring.

A crouching shape, scarcely more than the shadow of a living thing, a creature now wholly ruined and defeated, yet still filled with a hideous lust and rage; and before it stood stern, untouchable now by pity, a figure robed in white, but at its breast it held a wheel of fire.

Gollum has been devastated by the Ring’s absence, whittled down to unfettered emotion and desire. Frodo has been devastated by its presence, his own emotions and desires burned out to leave him a sort of husk for power. Frodo is “untouchable by pity,” which means that he is no longer Frodo.

But for the first time, Sam—all the while a counselor of cautious prudence and well-informed distrust of Gollum—finds himself standing in the shoes of his master. “Let us live, yes, live just a little longer,” Gollum cries to him after Frodo leaves him behind for the Cracks of Doom. “Lost lost! We’re lost. And when Precious goes we’ll die, yes, die into the dust.” A traditional Gollum argument, and one that Sam has heard before and been less-than-inspired by. But this time things are a bit different.

It would be just to slay this treacherous, murderous creature, just and many times deserved; and also it seemed the only safe thing to do. But deep in his heart there was something that restrained him: he could not strike this thing lying in the dust, forlorn, ruinous, utterly wretched. He himself, though only for a little while, had borne the Ring, and now dimly he guessed the agony of Gollum’s shriveled mind and body, enslaved to that Ring, unable to find peace or relief ever in life again. But Sam had no words to express what he felt.

“Oh, curse you, you stinking thing!” he said. “Go away! Be off!”

Just as the Ring strips empathy of Frodo it instills it in Sam. Suffering in moderation instills a deeper kindness and understanding in Sam, just as suffering is destroying Frodo mentally and physically (as it had done to Gollum long ago). Sam is the traditional hero. But it’s no wonder, really. Sam is the only character at Sammath Naur who is given suffering in accordance to his capacity.

Frodo’s Failure

Frodo’s “failure” is simple and happens quickly. I can’t quite explain to you how much this stunned me when I first read it. Frodo is often denigrated for being a passive hero. I have… little-to-no sympathy for this view. But I do understand the feeling of “wrongness” about it. So often fantasy heroism is about acts of will. This can vary widely in implementation, from toxic-masculinity-inspired murders to summoning some last reserve of magical power, or any variety of means of desperate resistance. Will wins. In this context, Frodo should dig deep inside himself, find one last reserve of power and will and hope. But he doesn’t. Frodo’s story hits its climax when his will is essentially entirely taken away, and he becomes, for all intents and purposes, an instrument. His story peaks in failure.

Tolkien received several letters about this moment over the course of his life (though, by his own admission, not as many as he’d assumed he would). He notes in a 1963 letter to Eileen Elgar that Frodo “indeed ‘failed’ as a hero, as conceived by simple minds: he did not endure to the end; he gave in, ratted.” In another he puts it in more explicitly theological terms: that Frodo “apostatized.” And some readers certainly agreed. Tolkien received a letter shortly after the publication of The Lord of the Rings that excoriated Frodo (and Tolkien himself), insisting that Frodo should not have been honored at the Fields of Cormallen but executed as a traitor.

But Tolkien is also clearly defensive of Frodo, and he insists over multiple letters that Frodo’s practical failure was in no sense a moral failure. The Ring’s power near the end, he writes, would be

impossible, I should have said, for anyone to resist … Frodo undertook his quest out of love – to save the world he knew from disaster, at his own expense, if he could; and also in compete humility, acknowledging that he was wholly inadequate to the task. His real contract was only to do what he could, to try to find a way, and to go as far on the road as his strength of mind and body allowed. He did that. I do not myself see that the breaking of his mind and will under demonic pressure after torment was any way more a moral failure than the breaking of his body would have been – say, by being strangled by Gollum or crushed by a falling rock. (Letter 246)

He goes so far as to criticize those who show such immediate disdain for Frodo’s experience in a letter to Amy Roland: “It seems sad and strange that in this evil time when daily people of good will are tortured, brainwashed, and broken, anyone could be so fiercely simpleminded and self-righteous.”

Grace and Pity

The choice to make Frodo’s task impossible is an interesting one on Tolkien’s part, and uncommon. Most fantasy drama stems from the seemingly impossible—low odds designed to heighten stakes, but always possible to overcome through enough smarts, faith, or Chosen One Powers. Impossibility seems to only promise two options: failure or deus ex machina, both of which have their share of narrative problems.

Tolkien’s choice of failure, though, is rooted in his conception of grace. I’ve often minimized the role of Tolkien’s faith in his writing. It’s not something I’ve tried to do intentionally, but as someone who doesn’t share his worldview, I often simply don’t find it the most interesting reading of his work. But I do think it’s somewhat unavoidable in “Mount Doom.” Frodo, and the Quest, are of course saved by pity: Frodo spares Gollum, allowing Gollum to be there at the key moment to cast the Ring (and himself) into the fire. This, Tolkien himself notes, is in many ways an “irrational” choice.

At any point any prudent person would have told Frodo that Gollum would certainly betray him and could rob him in the end. To ‘pity’ him, to forbear to kill him, was a piece of folly, or a mystical belief in the ultimate value-in-itself of pity and generosity even if disastrous in the world of time. He did rob him and injure him in the end – but by a grace, that last betrayal was at a precise juncture when the final evil deed was the most beneficial thing anyone could have done for Frodo! By a situation created by his forgiveness, he was saved himself. (Letter 181)

Note the passive tense. Tolkien’s moral universe—particularly at Mount Doom, but throughout his entire legendarium—is rooted in the idea that people are finite in the powers and potentials and are often extended into spheres beyond their capacity. In this situation, they are both in need of external salvation that they cannot possibly demand or expect, but also empowered: to live the sort of life that places them in a position to receive such grace.

We are assured that we must be ourselves extravagantly generous, it we are to hope for the extravagant generosity which the slightest easing of, or escape from, the consequences of our own follies and errors represents. And that mercy sometimes occurs in this life. (Letter 192)

The Lord of the Rings is a passive book in many respects, for all its wizards and wars. It is inherently responsive, and its core thematic thrust refuses any extravagant display of will and power, even for the greater good. Such an act is inherently arrogant for Tolkien, insisting on creative control rather than care and “extravagant generosity” to those around us. Such an act would be an assault on the role of God as Master Storyteller. And such judgement of others would be ass assumption of the role of God as judge:

Frodo indeed ‘failed’ as a hero, as conceived by simple minds: he did not endure to the end; he gave in, ratted. I do not say ‘simple minds’ with contempt: they often see with clarity the simple truth and the absolute ideal to which effort must be directed, even if it is unattainable. Their weakness, however, is twofold. They do not perceive the complexity of any given situation in Time, in which an absolute ideal in enmeshed. They tend to forget that strange element in the World that we call Pity or Mercy, which is also an absolute requirement in moral judgement (since it is present in the Divine Nature). In its highest exercise it belongs to God. For finite judges of imperfect knowledge it must lead to the use of two different scales of morality. To ourselves we must present the absolute ideal without compromise, for we do not know our own limits of natural strength (plus grace) and is we do not aim at the highest we shall certainly fall short of the utmost that we could achieve. To others, in any case of which we know enough to make a judgement, we must apply a scale tempered by mercy: that is, since we can with good will do this without the bias of inevitable in judgements of ourselves, we must estimate the limits of another’s strengths and weigh this against the force of particular circumstances. (Letter 246)

I have… intensely mixed feelings about this. Tolkien’s view of moral judgement manages to simultaneously be an open-minded philosophy of tolerance and understanding and a terrifying blueprint for debilitating Catholic Guilt. His view of grace and its role in the world both puts a deeply admirable emphasis on the treatment of individuals but also has an inherent hesitation towards any bold challenge to systems and structures. I find it both beautiful and very off-putting.

Final Points

- “Well this is the end, Sam Gamgee.” It’s not, of course. Not by a bit. It’s the first thing Frodo says as his full self in perhaps the entirely of The Return of the King. He assumes that, the Quest completed, he’ll now be allowed to die: the best-case scenario he’d been envisioning for weeks. He won’t and the rest of The Return of the King will explain the really important question of what that means. As Tolkien notes in one of his letters, Frodo was widely celebrated for his effort and his heroism and “all who learned the full story of his journey.” But he also notes shortly after: “what Frodo himself felt about the events is quite another matter.” I’m looking forwards to exploring this.

- Frodo is aware, before they reach the Mountain, that he is unable to give up the Ring. I do wonder what he thought would happen when he reached the Cracks of Doom. There’s no happy answer to the question. It also makes sense that Sam would not be able to acknowledge and process this possibility, even though Frodo literally tells him it’s the case.

- For all of the jokes at the expense of the Minas Tirith linguist in Book V, we do see here how words and language are such a gift for Tolkien. Sam’s empathetic epiphany towards Gollum remains nebulous and unformed, all simply because he doesn’t have the proper words to express it.

- Prose Prize: I hadn’t really remembered Tolkien’s evocation of Sauron’s fall, but it’s really good. A brief vision he had of swirling cloud, and in the midst of it towers and battlements, tall as fills, founded upon mighty mountain-throne above immeasureable pits; great courts and dungeons, eyeless prisons sheer as cliffs, and gaping gates of steel and adamant: and then all passed. Towers fell and mountains slid; walls crumbled and melted, crashing down; vast spires of smoke and spouting steams went billowing up, up until they toppled like an overwhelming wave, and its wild crest curled an came foaming down upon the land… And into the heart of the storm, with a cry that pierced all other sounds, tearing the clouds asunder, the Nazgul came, shooting like flaming bolts, as caught in the fiery ruin of hill and sky they crackled, withered, and went out. I’m really struck but how abstract and tangible it is at the same time. And the description of the Nazgul fizzle out into nonexistence is such a vibrant point upon which to end. I’d like to have written more about this because there’s lots of good stuff but man, this essay is so, so long.

- BUT I also very much like “the magnitude of his own folly was revealed to him in a blinding flash, and all the devices of his enemies were at last laid bare. Then his wrath blazed in a consuming flame, but hear fear rose like a vast and black smoke to choke him. For he knew his deadly peril and the thread upon which his doom now hung.”

- Contemporary to this Chapter: Tolkien is careful to establish here how Gandalf’s plan is working as well as can be hoped for. As Frodo and Sam make their way to Mount Doom, all of Mordor is emptying out towards the Morannon and the approaching host.

- Very excited for a six-chapter denouement.