Lupin the III: The Castle of Cagliostro occupies a strange space in pop culture. It is the most well-known Lupin film because it is the feature debut of legendary Japanese animator Hayo Miyazaki. However, it is among the least well-known Miyazaki films or, at the very least, rarely discussed by comparison.

The Castle of Cagliostro is not Miayazki’s first dance with the gentleman thief Lupin (Yasuo Yamada). Miyazaki and his Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata had worked on the Lupin III television series, taking over for Masaaki Osumi. Still, when The Castle of Cagliostro rolled around, Miyazaki had seeming had his fill of the bumbling, lecherous hero with a heart of fool’s gold.

Though in Miyazaki and Takahata’s hands, Lupin had transformed from the horny egoist created by the manga artist Monkey Punch into a horny rascal and his merry band of idiots causing all kinds of anarchical jackassery. Miyazaki and Takahata toned down the violence and debauchery of earlier Lupin and, in so doing, allowed more possibilities for creativity.

The YouTube channel Infinite Snow Productions deftly observes, “Compared to the first run episodes of “Lupin the III” where most things are solved by Lupin being the coolest, most talented to ever live, you see a lot more improvising and petty scheming to the point where you realize that if this were anyone other than Miyazaki and Takahata, they might have accidentally invented “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” twenty five years early.”

However, the Castle of Cagliostro doesn’t play with this dynamic, mainly because Miyazaki set the story ten years into the future. I wouldn’t call the older Lupin a wiser one, but with being never quite sure of what’s going on inside that noggin of his, we learn that Lupin harbors more regret than one would expect.

Lupin and his merry band of misfits always somehow find ways to invent new levels of chicanery. The wannabe Humphrey Bogart Jigen (Kiyoshi Kobayashi), the stoic bad-ass samurai Goemon (Makio Inoue), and the ultimate femme fatale, Fujiko (Eiko Masuyama) can’t help but follow Lupin wherever he goes.

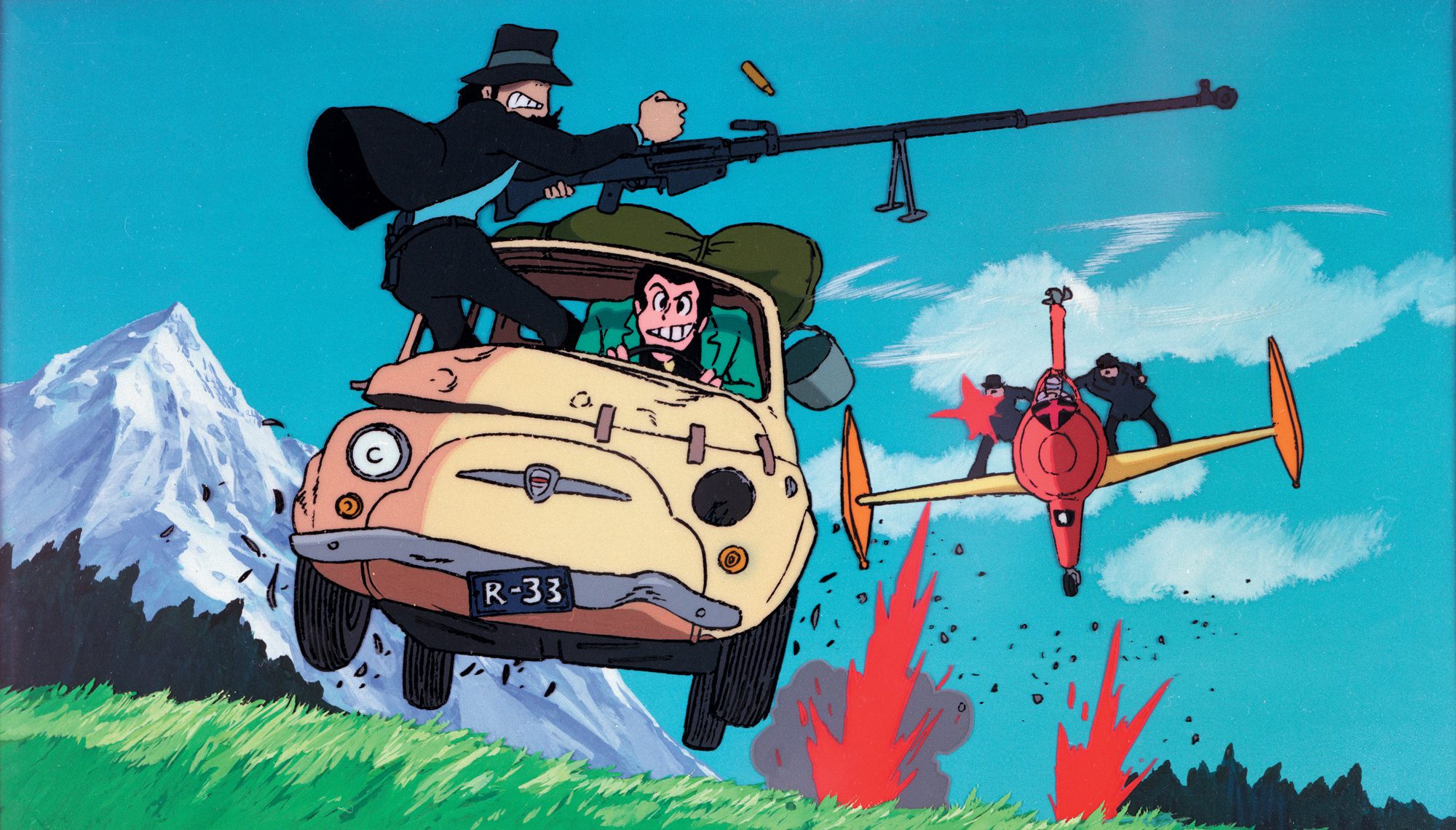

Like all Miyazaki films, there’s a flow to the story that feels gentle and sure. The Castle of Cagliostro starts with Lupin and Jigen robbing a casino only to discover that it’s some of the best counterfeiting they’ve ever seen. The joy of The Castle of Cagliostro is how that turns into Lupin stumbling into memories of his past, uncovering a worldwide conspiracy, an incestuous wedding with a sex pest, and one of the best car chases ever put to film.

I’m not being hyperbolic. The chase at the beginning of The Castle of Cagliostro illustrates everything that makes Miyazaki great and different, from the fluidity of movement to the delicate balance of cartoon physics and real physics and understanding when to violate one or the other. The chase scene takes on a breathless excitement as we witness Miyazaki and his animators relish the freedom of movement, translating into a visceral excitement.

It’s not just the movement in The Castle of Cagliostro that fascinates. But the way Miyazaki and his animators take the time they didn’t have in the four months it took them to animate tiny mannerisms. The way Jigen and Lupin sit while they wait for a passing train to go by, the way Jigen toys with his cigarette, how people in crowd scenes move, or how the wind tickles blades of grass. The world in The Castle of Cagliostro is alive, and Miyazaki can barely contain himself as he shows all the little ways it breaths and moves.

The Castle of Cagliostro also understands that the roles of the characters are not set in stone, but their destinies are. Inspector Zenigata (Goro Naya) will work with Lupin to bring down the vile Count Cagliostro (Taro Ishida). But that doesn’t mean Zenigata won’t arrest Lupin when it’s all over. It allows for shifting allegiances while keeping the characters’ natural antagonism intact.

Zenigata, long a thorn in the side of Lupin, will stop at nothing to bring Lupin in. However, despite his obsession, he understands the difference between Lupin and a nefarious villain who has caused economic collapse, funded wars, and killed countless people. The Castle of Cagliostro is whimsical and fun, but Miyazaki shows his hatred of senseless cruelty and corruption early in his career. As evidenced by a scene late in the movie when Zenigata brings evidence of Cagliostro’s crimes before his superiors. He quickly realizes that they are all on Cagliostro’s payroll, or worse, scared of doing anything.

It’s a heartbreaking scene as Miyazaki and his animators show the pain and furor in Zenigata’s face. He is dedicated to upholding the law and powerless to do so because those above him lack the moral spine or the capacity to stand up. Zeniagata is one man in a corrupt system, and for a few scenes, we see that full realization hit him in a way that feels similar or prescient to how Miyazaki would come to view anime as a whole.

Contrast that with the mystery at the heart of The Castle of Caligistro, which is how Lupin knows the damsel in distress, Lady Clarisse (Sumi Shimaoto). The answer is that he’s been here before. Later on, we learn from Lupin himself he was shot trying to rob the Count, and Clarisse, then a child, nursed him back to health. Incredibly, he had forgotten the whole thing, never dwelling on any of it.

It rhymes with something we learned about Lupin in The Mystery of Mamo: Lupin doesn’t dream. Lupin’s confession about knowing Clarisse gives us a glimpse into a man who lives so in the now that the future and the past hold almost no meaning to him. A fact that Lupin himself finds troubling.

Cagliostro himself is a compelling villain. Largely mysterious, he seems charming and refined, the kidnapping of Clarisse aside. The way he looks amused by Lupin’s antics and how he invades Clarisse’s personal space makes him unnerving. His obsession with Clarisse is more than merely trying to find a treasure and much more legitimately creepy perversions. Incest aside, it also becomes creepy because it’s never quite clear how old Clarisse is. At times, she seems like a child and at others like a young adult, making Cagliostro’s attraction to her all the more skeevy.

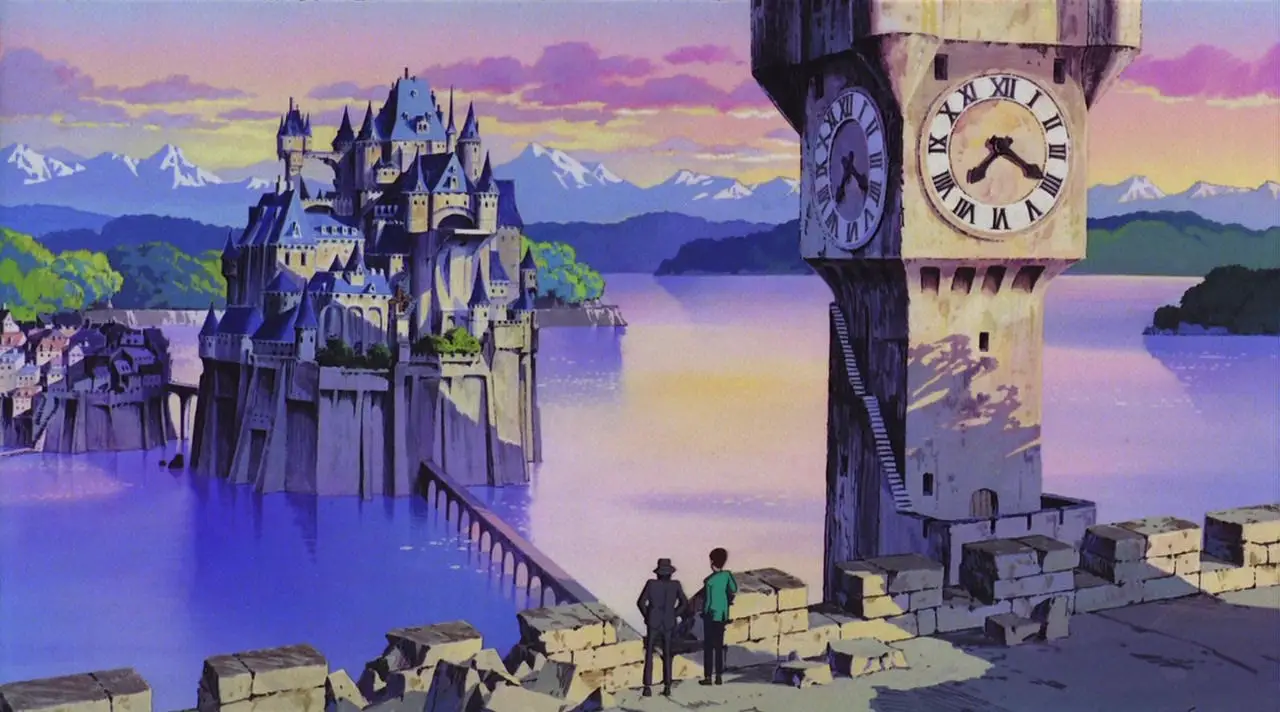

From the get-go, we see Miyazakia cramming The Castle of Cagilostro with action, whimsy, intrigue, and meditative shots of nature. But Miyazaki is also finding ways to tackle complex emotional issues without putting a name to them, delving into issues of powerlessness, exploitation, and regret, thus giving The Castle of Cagliostro a hint of melancholy that makes it possibly one of the more haunting of Lupin’s adventures.

So much so that many of the characteristics of both The Castle of Cagliostro and of Miyazaki reverberate through later Lupin films. The innocent maiden who believes she can save Lupin or, the most egregious, make Lupin bleed. A moment in The Castle of Cagliostro that never fails to shock me.

The instant perfectly exemplifies how Miyazaki threads the needle between reality and Wile. E. Coyote physics. The Castle of Cagliostro sees Lupin jumping from castle turret to castle turret, almost flying in some aspects, driving on the side of a mountain. Still, Lupin is as human as anyone when it comes to a bullet. Miyazaki uses the moment to allow Lupin his exposition as he recovers and as a device to get Lupin to look at himself. It’s not just done because no one would expect it.

Despite being inventive, lush, and whimsical as The Castle of Cagliostro is, fans of Lupin don’t consider it an actual Lupin film both because of the time jump and the uncharacteristic introspection by Lupin as well as how little of a role Jigen, Goemon, and Fujiko play. A bastard child, The Castle of Cagliostro is at once tolerated by fans, and yet few deny its brilliance and artistry.

Fujiko’s role in The Castle of Cagliostro differs from other Lupin films. Like Jessica Rabbit, Fujiko is a character more famous for her character design than her actual characteristics. A devoted foil to Lupin, the two are meant for each other, if for no other reason than that they are the mirror image of the other. Every bit as petty, bratty, and amorous, she keeps Lupin on his toes, and I love her for it. Though in The Castle of Cagliostro, she’s used more as a Get Lupin out of Jail Free card.

However, Miyazaki does give her a fantastic scene during the wedding where she poses as a news reporter. Fujiko stands above the crowd as Lupin, Jigen, Goemon, and Zenigata wreak havoc and, like a WWE color commentator, tells the audience at home what’s going on. The cherry on top is how she takes brief time-outs to kick whichever foolish henchmen try to attack her or her cameraman, who, as far as I can tell, is an actual cameraman who got roped into this thing. That moment, that was pure Fujiko.

Ironically, Miyazaki’s Castle of Cagliostro plays well whether or not you’re familiar with Lupin III. It’s a stand-alone gem that builds on established characters and feels removed from them at once. The movie ends with the good-bad guys winning, the bad-bad guys losing, and Zenigata chasing after Lupin again.

Clarisse begs Zenigata to leave Lupin alone; after all, he didn’t steal anything. Zenigata smiles, “He stole something outrageous. Your heart. Chase Lupin! Chase him to the end of the Earth.” Like all adventure movies, the treasure was hardly the point, and in the end, everyone resets back to their starting positions despite any deals or arrangements made during the story.

The Castle of Cagliostro is a reminder of how abusrd that a phrase, a lesser Miyazaki, is. Any other director would be tickled pink to have a light-hearted adventure with little moments of pathos waiting to be discovered. But for Miyazaki, it’s only the beginning.

Images courtesy of Toho

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!