Marie: You’re smiling. Back at the bar, you acted as if you had some big trouble on your shoulders.

Jim: They come and they go.

Marie: Troubles?

Jim: Smiles.

A lot of people consider the 1956 noir Nightfall a slight film, and in the context of Jaques Tourneur’s career, maybe it is. But I love it too much and find it far too fascinating to dismiss it so easily. Also, chalk this up to yet another movie I’m sure Tiny Toons riffed on at some point.

Tourneur is a name I fear may be lost to many modern movie buffs. Yet, his films aren’t. From Cat People to Night of the Demon, Tourneur made westerns, noirs, and horror pictures. He made his name by making pictures for the producer Val Lewton, who had an impressive run of films during the 40s. Tourneur’s movies, whether under Lewton or someone else, always manage to evoke a kind of uneasiness, a dread that percolates unmentioned but is always present.

The dread in Nightfall may not be as potent, but it’s there. Like all noirs, there’s something off about everything. There’s a sense that all isn’t right. Its genre often deals with the randomness and cruelty of systems to the degree that if we lived in an era with a functioning Hollywood, it would be a booming genre fitted for our troubled times.

Stirling Silliphant’s script, adapted from David Goodis’s book, is lean while not as mean as most other noirs. But that isn’t to say it’s a cuddly picture. Its teeth are sharp enough to cut you if you’re not careful. Still, for a genre that popularized complex plots so tangled that even the writers didn’t know all the answers, Siliphant’s script is straightforward.

Aldo Ray’s Jim Vanning is an everyman on the run. Why? Because through no fault of his own, he’s being hunted by police and a pair of blood-thirsty bank robbers. Nightfall drills into how the world can turn against a person instantly, seemingly almost as if a sadistic God was having a good laugh at all the ants down below.

But first, I must confess this is my first Aldo Ray film—or at least the first film in which I noticed him. He seems like a man flung out of time: a hunky linebacker with a baby face, a soft, raspy voice, and zero affectation. He doesn’t have the Bogart or Mitchum mug, but something about his presence is compelling.

My wife put it best: He seems like a modern actor in a 1950s film. All of this is to say that Ray might not be the best leading man, but he is a fascinating one. As the unlucky James Vanning, his matter-of-fact nature goes against the grain of the genre archetype while also embodying it.

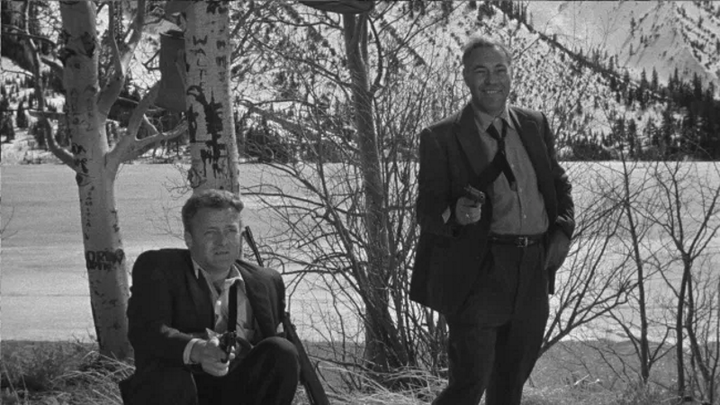

Now, if Ray was the only good thing in Nightfall, I could understand the tendency to call the film ‘slight.’ But we haven’t even gotten to a pair of psychopathic bank robbers, played by Brian Keith and Rudy Bond, as John and Red obsessively hunting for Vanning.

Keith, the cool and collected leader of the duo, and Bond’s sadistic giggling sidekick also make Nightfall memorable, if only because of their casual brutality. The two have combustible energy that adds an anxious menace for the 50s, or any time. Not to mention how you can sense that it’s not loyalty the two share but more of an uneasy truce.

Then there’s James Gregory as Ben, the insurance agent hot on Vanning’s trail. Gregory is largely there as an exposition dump and as an audience surrogate. He’s conflicted. He’s trailing Vanning for his Insurance company, and despite how innocent Vanning appears, he also behaves like a guilty man trying not to be noticed.

Oh, I didn’t mention Anne freaking Bancroft! Bancroft pairs nicely with Ray, her baritone voice a lovely contrast to Ray’s own unique timbre. Silliphant’s script may take her from stranger in a bar to loyal lover a bit too quickly, but this noir logic is the least of our worries. Besides Bancroft’s, Marie has one of my favorite moments where she stops in the middle of a tirade directed at Vanning and politely asks for a cigarette before continuing to rip into the guy.

Talk about a dame.

Perhaps what makes Nightfall so easily dismissed is its lack of psychological depth compared to both the genre and Tourneur’s other works. It’s not as rich as his other famous noir, Out of the Past, or as filled with dread as The Leopard, an early Val Lewton film that is among the first to deal with the notion of a serial killer. One could even call it an early slasher.

But Nightfall contains its own pleasures. Silliphant’s script stuffs the script chock-full of tough-as-nails dialogue mixed with poetic prose with an underlying archness that borders on sly parody. Such as when Ben tells Jim everything will be fine, he reminds him, “Don’t forget the dandy.”

To say nothing of how Silliphant structures the story. People have pointed out that the story is too contrived and that everything happens by coincidence. To say nothing of the flashback that happens directly in the middle of the film. But that’s the point. Silliphant and Tourneur are looking at how unfair, unfeeling, and relentless the universe is. You can’t outrun your future, or as Vanning does, wait around until the perfect moment.

Guffey and Tourneur undermine this by having so much of the film take place during daylight. Yet Guffey still finds moments to play with shadows that lend a haunted air to the film. Tourneur’s staging strips away the more surreal and dream-like quality associated with the genre but still holds onto the illusory qualities even as he crafts a more realistic natural aesthetic.

Instead, substituting it for a starkness, a bleakness. The vast, snow-covered Wyoming wilderness a visual representation of how tiny and insignificant we are. There’s beauty, but it lies there and does not care for the brutality before it.

Calling Nightfall too coincidental to be believable misses the point. “Things that really happen are always difficult to explain.” The past is filled with bank robbers, cops, dead friends, frame-ups, and money hidden in the Wyoming wilderness. The present is about trying to deal with the refuse of the past while the future happens before your eyes.

Nightfall is about how things just happen. How some people, like Vanning, are just unlucky. Part of what makes Nightfall so gripping is Vanning didn’t do anything to cause this; he just went camping. He was just camping with his best friend, and before he knew it, he was being framed for murder and almost forced into committing suicide. He is now on the run from the law and two madmen.

There are many notes from Nightfall that remind us of Fargo, especially the way the dry comedy blends in with the horrific. There’s a scene with a runway snowplow that feels like something. I imagine the Coens giggled incessantly at how absurd yet effective it was.

Nightfall is compelling, if for no other reason than that, despite its trappings, it zigs where it should zag. Whether it’s how much of the film takes place in broad daylight or how there’s a foot chase that takes place at a fashion show, Tourneur, Silliphant, and Guffey lean into the idea that a noir feels like a nightmare come true. Yes, it may have a happy ending, but the shadow that it could all happen again, to anyone, over the neatly tied bow.

Images courtesy of Columbia Pictures

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!