“…I have little regard for an art that deliberately aims to shock because it is unable to convince.”

— Albert Camus, in the 1957 preface to Caligula

The Season 6 trailer for Game of Thrones came out last week. If you haven’t yet, take a look at Kylie’s reaction post then come back. Don’t worry I’ll wait.

Right, moving on. From the comments section of Kylie’s post, it is safe to say that many show watchers who come to this site are, quite frankly, bored, which is the exact opposite reaction the showrunners David Benioff and Dan Weiss (D&D) are going for. They clearly want to be Shocking™ and Unexpected™ and Brave™. From Bran seeing the “Night’s King” in a green dream to the ‘unknown’ knight wielding two swords, we’re clearly supposed to be in awe, wondering what possibly could be coming next!

But, we’re not. We’ve seen this before, and even what we haven’t seen is unimpressively familiar. That feeling of having seen it before, of knowing how things are going to be, and feeling decidedly empty and bored because of it, is called “acedia” and that is what I want to talk about.

Acedia: A Brief Definition

Chances are, you’ve never heard the word acedia before. Until a few months ago, I hadn’t either. It is an ancient concept, used primarily in monastic circles in the first several centuries AD to describe a feeling of boredom or malaise (lack of caring) that stems from a life of repetition and routine. It is not clinical depression by any means, though one can cause the other. You know that feeling when life seems the same, that nothing will change at all ever, that all your efforts to keep on doing the things are worthless, and you are doomed to a life of nothingness that ends in death? That’s acedia.

“You know the pain is there, yet can’t rouse yourself to give a damn.”—Kathleen Norris, “A Conversation with Kathleen Norris”

You literally can’t make yourself to care, whether from boredom, despair, sorrow, or some combination thereof. Again, this is not clinical depression. If it seems like I’m splitting hairs, it’s because I want to be very clear that acedia is not a mental illness. Depression is a bodily illness with psychological and physiological bases. Acedia is a sickness of the spirit or will. You don’t particularly want to do anything and you definitely don’t care. It’s a numbed boredom with how meaningless and dull life seems, in other words, it’s spiritual morphine.

A Culture of Acedia

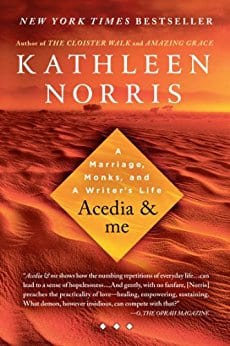

All of this can be found in Kathleen Norris’ book Acedia & Me, which my sister gave me for Christmas and I’ve been devouring avidly over the past few months. On its own merits, it’s a great book: fascinating, compelling, challenging, and beautiful. It’s very meaningful to me and my journey through life the past several years. It’s also very timely as I happen to live a life that is prone to acedia. Like the ancient monks, I work from home and have a daily routine that can very easily become tinged with ennui. While I am introverted and prefer solitude most of the time, I do the same thing every day with little to no interaction with others and that can lead to restlessness and apathy. Plus, I’m just prone to acedia because of my temperament.

So much for me personally. In her book, Norris also describes our (Western, 20th/21st century, American) society as one that thrives on and perpetuates a culture of acedia. Rather than ushering in a utopian era of human freedom, the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries and the Industrial Revolution culminated instead in two world wars, horrific chemical weapons, concentration and prison camps around the world, and the atomic bomb. Widespread access to world news with the advent of radio, television, and the internet means that we are more aware of the mass bombings, genocide, and hate fueled violence aimed at women, the LGBTQ community, and religious and ethnic minorities. No matter what human society was told in the 19th century, we are not a “civilized” society.

Yet despite all of the evil in society and the world, we don’t really care about it. We can look at a starving child and say “at least that’s not my child” and move on without helping. We can see a homeless person and convince ourselves they must be lazy and therefore, undeserving of our help. We fill our lives and our schedules with “things to do” and tell ourselves it means we’re not lazy, we’re productive. But we are numbing ourselves to care. We do so much that we don’t have time to think, which means we don’t have time to care. We consume media and entertainment and products but are numb to the tragedy and pain and suffering in the world.

The ability to only care about things that personally affect you and your life is a form of societal acedia; we no longer care about the life of the community or the nation at large, unless it affects us personally. We don’t care about gun violence, just that individuals can buy a gun. We don’t care about MS or cancer until a family member or celebrity talks about it. We care about bombings in America or Europe, but not about suicide bombings in Africa.

Surrounded by violence and with a news media that depicts the outrage over a sexual predator attacking women in the same way it depicts the outrage over rising oil prices, it’s no wonder we’re apathetic. We are told about a black man gunned down by police in the same tone as we’re told about a new library opening in our neighborhood. How are we supposed to care about all of these things in the same way? It’s easier just to not care at all, especially when we’re busy enough and distracted enough to not think and feel.

Acedia and Game of Thrones

Thanks for the history lesson, Gretchen, but what the hell does this have to do with Game of Thrones? Well, it’s the same principle. Kylie and Julia have mentioned in various Tumblr posts about how the nihilistic world that D&D have created engenders a sense of apathy. Weisseroff is Darkness Induced Apathy at its very finest. D&D depict Sansa’s rape with the same tone as they depict Arya losing her eyesight. We’re supposed to believe that these are equivalent tragedies for these young women, but at some level, we know they’re not. Tellingly, the most prevalent response is to downplay Sansa rape rather than, say, oversell Arya’s blindness. The audience downplays violence and tragedy because it doesn’t care.

This is exactly what acedia is, a lack of care so ingrained that even brutal rape cannot engender any kind of concern from the audience. They’ve thrown so many bodies of brutalized women and children at us, that another body burned induces a yawn instead of revulsion. The sexual exploitation of Carice van Houten as Melisandre flashing her boobs is old hat. In a fictional world where a jerk getting his head cut off is “gratuitous,” but an 11 year old child being burned is perfectly fine, how are we supposed to react with anything approaching normal human emotion?

And this doesn’t even begin to touch on how their tactics reflect the acedia of society around them. How can we expect most people to be concerned about what D&D did to Sansa when our culture actively shames rape victims, calling them liars and attention seekers who failed to adequately respond to their abuse? Either by fighting the person off or by not being ‘empowered’ by it. Or, even worse, we silence rape victims and say they made the whole thing up. How can we expect people to care about Shireen being burned when children all over the US are starving and living on the streets and instead of helping, we feel satisfied so long as they’re not our children?

Tempting as it is to blame D&D for the level of acedia that their Shock and Awe™ tactics create, they’re not entirely to blame. Yes, they are contributing to a culture of apathy, but they also seem to be drinking their own Kool-Aid. Let’s go back to Sansa and the famous (or infamous in these circles) quote about Sansa’s Winterhell plotline.

“You have this storyline with Ramsay. Do you have one of your leading ladies—who is an incredibly talented actor who we’ve followed for five years and viewers love and adore—do it? Or do you bring in a new character to do it? To me, the question answers itself: You use the character the audience is invested in.”—Bryan Cogman

To put it bluntly, the GoT writing team didn’t believe that the audience would be invested if the character weren’t Sansa. They believed that the audience wouldn’t care about some nobody getting raped, and you know what, they’re right. Many people in the US don’t care if a poor black woman gets raped or if a homeless teen who was kicked out for being a lesbian is raped. D&D seem to believe and also reinforce the message that rape only matters if it is important people.

Trouble is, this is precisely the message that GRRM is trying to fight. They’re giving into the narrative of our culture that you ought to only care about ‘important’ figures and what happens to them. “Poor people? Homeless? POC? Trans? Who cares. They’re not me, so they don’t matter. Only important people matter; people like me.” GRRM’s message undercuts this because when you read about Jeyne, you do care. You can’t NOT care. And Theon cares. Despite his ‘training’ by Ramsay to care only about himself as a victim and preserving his own life, Theon learns to care. Theon, a young man who once epitomized the gentrified attitude of not caring about the smallfolk, he learns to care about her enough to save her.

Martin finds a way to make his audience care about Jeyne and her suffering precisely because she is a character that most would write off as unimportant, because to him, we ought to care about more than just the POV characters. This is a far cry from D&D’s insistence that the audience can only care if it is a character you’re already invested in.

In fact, as @turtle-paced has pointed out in her Game of Thrones rewatch fine-toothed comb edition, the show has consistently left out the plight of the smallfolk, which is quite a major backdrop of the books. Tywin overreacts to Tyrion’s kidnapping and Robb claiming to be King in the North by waging a war on the smallfolk of the Riverlands, leaving the vast majority of the land a bloody, smoking ruin. We start to see it in AGoT when smallfolk come to the king for justice. The stories are disgusting, heartbreaking, and manifold. We see just how bad Gregor Clegane’s rampage through the Riverlands is in Arya’s ACOK’s arc, and it’s bad. The television show leaves this out for the most part. Oh we get bits and pieces in Arya’s plotline in Seasons 2-4, but it is much more limited than what we see in the books. Why? Probably because they don’t think we’d care. The smallfolk aren’t ‘main characters’ and the ‘main characters’ are all that matters. It’s all we’d be emotionally invested in.

This also applies to how they reframe the Faith in S5. Instead of the Faith Militant being a response to the atrocities the gentry have heaped upon the smallfolk (atrocities they’ve left out), the Faith Militant is concerned about people’s sexuality that just so happens to affect, you guessed it, our main characters. The Faith Militant doesn’t care about poor people, they only care about whose hole the rich people are putting their dicks into. Because that makes sense.

Again, this is an assumption on D&D’s part that we don’t care about the plebs, the poor, the smallfolk. We only care about “important people” like Loras, Margaery, and Sansa. We don’t or can’t care about poor Jeyne Poole. We don’t or can’t care about the horrible things Tywin is doing to the smallfolk in the Riverlands, the starving masses whose homes and livelihoods went up in flames because some lord got pissy with another lord. According to the story they’re giving their viewers, the war only affects the wealthy POV characters, not the masses. Martin might not give us many POV characters who aren’t aristocracy (one thing I wish he did better), but he does give us Davos (a smuggler) and Areo Hotah (a guardsman). Plus, through Arya, Dany, Tyrion, and Jon, we get to see how war is affecting the smallfolk, Wildlings, and slaves not just in Westeros, but in Essos as well.

But it isn’t just the steady string of brutal violence heaped upon the main characters that shape Weisseroff into a depressing, nihilistic heap of nothing. War might be raging in Westeros in Martin’s novels, but unlike in GoT there are enough characters who actively resist the existential despair of war that he avoids the nihilism so rampant on GoT. For example, despite the indoctrination of the Faceless Men, Book!Arya cannot bring herself to not care about her family or the injustices done to them. Her victory is that she maintains her identity and her connection to her family despite her trauma. In the show, we get revenge. Not that revenge isn’t worth exploring, but is it more interesting than a child soldier attempting to maintain her familial and communal ties in the face of a secret society that attempts to erase her personality and turn her into an emotionless killing machine for hire? I know which I prefer.

Sansa is the epitome of victory over nihilism. She actively (albeit mentally) refuses to capitulate to the antipathy and heedlessness of others that characterize the powerful people in her life: Cersei, Littlefinger, Sandor, and even Tyrion to some degree. She goes out of her way to restore the faith of one of the victims of the messed up system (Sandor). Indeed, one of the many things she and Arya have in common is how much they care about other people.

Sansa wants to make the people love her, should she ever be queen, which means taking an active interest in their welfare, and she goes out of the way to get the people of the Eyrie to like her. She cares for and about Sweetrobin despite him being a little prick to lots of people. Arya interacts with the smallfolk and commoners in Winterfell, King’s Landing, the Riverlands, and Braavos. She draws people around her and engages in their concerns, creating a pack wherever she goes. Rather than just learning about them (e.g., three new things), she gets to know them. Same with Sansa. She knows a lot about the people of the Eyrie, as LF does, but she also makes real friends and engages in the suffering of others. The Stark sisters are defined by their empathy, which is the opposite of acedia.

But there are others. Dany refuses to ignore the suffering of the slaves, though she is told point blank to leave them alone and let the culture of Slaver’s Bay exist as is. Jon refuses to ignore the suffering of the Wildlings even though he is told to leave them alone and let them die beyond the wall because they don’t conform to Westeros’ political system. Jaime is in the process of learning how to care about people who are not Lannisters. Tyrion’s ADWD’s arc is starting to break him of his own Lannister obsession with being “worth more” than others, though he is still not at the point where he is capable of caring about anyone other than himself. Yet.

Almost all of these features are either destroyed or so badly mangled by D&D in Game of Thrones that their impact is lost. Jon’s concern for the Wildlings is overshadowed by the persistent xenophobia of the Night’s Watch. It doesn’t help that he’s frequently called stupid and never shown doing anything. The audience might commend him for his lack of racism toward the Wildlings, but this message is drowned out by the overwhelming negativity that is Jon’s fOlly. The same criticism applies to Dany’s anti-slavery campaign in Slaver’s Bay. Her infantalization, erratic behavior and choices, coupled with the White Savior overtones and the Ser Friendzone subplot undercut any power or positivity that could be had in Dany’s attempts to overthrow a truly disgusting system of slavery.

Cutting the interactions between Sansa and Sandor have the same effect on the narrative. His “there are no true knights” is frequently the last word in their interactions, meaning that his cynicism wins out over her hopefulness. As the seasons progress, the snuffing out of human decency gets worse. Acts of kindness by any character are frequently used to set up even worse atrocities later on in the narrative. Rather than a gloomy place with bright, hopeful glimpses of human decency, we are given a metaphorically (and literally) dark world where any kind of hope is like Sansa’s tiny candle in Winterfell: ineffectual and meaningless.

Side Bar: Game of Thrones and “Narrative Sadism”

But it’s more than just darkness induced apathy. This is a narrative that doesn’t just lull or even force you not to care because of how depressing it is. It actively punishes you for caring. Just look at Stannis, Shireen, and Myrcella. D&D actively built up these characters precisely so that they could then ‘shock’ you with their deaths. More than that, it punishes emotional investment and mocks you for it. “Ha! I got you to care and oh no she’s dead, so there!” Sucker punch. This is beyond apathy. At best, it’s writing for clickbait headlines the next day: “You’ll never guess what happened on Game of Thrones!!!” At worst, it’s sadism. They delight in punishing their audience for any kind of emotional investment they might have in a character purely for their own enjoyment.

Some might say, “but characters die in the novels, so you can’t blame D&D”. Oh yeah? Just watch me. What Martin does is a far cry from narrative sadism. The Red Wedding wasn’t so much a sucker punch as it was a dénouement after a slow buildup of doom. There’s Dany’s visions, Robb’s marriage to Jeyne Westerling, Roose’ war council (Roose and the Freys had already decided to betray Robb even before his wedding to Jeyne), and Cat’s own fears.

For all that people project sadistic pleasure onto Martin’s writing, it just isn’t true of him. He’s not trying to sucker punch his audience with ‘shocking’ twists. If you reread ACoK, all the markers that point to the Red Wedding are there, they just only make sense in retrospect. Robb’s death wasn’t a sucker punch so much as slow, impending doom. It was gruesome and horrific, but that’s not the same as Shocking™. For D&D, shocking means actively stating (or heavily implying) the opposite will happen then doing the thing anyway. Like with Stannis and Shireen. Stannis says that he loves Shireen too much to have her sent away to a leper colony, but as soon as there’s a hint of trouble, he burns her. That’s Shocking™, presumably because it makes no goddamn sense narratively or characterization-wise. With the release of the S5 Blu Rays, we got this little nugget of knowledge:

“40. The scene of Stannis telling Shireen the story of her greyscale was included to build their relationship and make his betrayal of her all the more painful when she is sacrificed to the God of Light in episode nine.”—Game of Thrones Season 5: what we learned from the Blu-rays

There it is, plain and simple: they wanted to inflict maximum pain. The writers actively lead you to believe that Stannis is a loving father who cares for his disfigured daughter, only to punish you for your emotional investment in their relationship by having Shireen burned.

This is even more true when you look at Stannis himself. In the book series thus far, Stannis is very much alive and poised to fight Roose Bolton for the North (and quite possibly win). In Stannis, Martin has created a character that many people have mixed feelings about. While many people I know who read the books aren’t the biggest Stannis fans, I happen to find him very compelling, especially upon reread. The point is that Martin didn’t intentionally set out to create an emotional bond between every reader and Stannis. If he’s your jam, cool. If not, at least the Northern plotline is interesting (unlike, ahem, GoT and Winterhell). I’m pretty sure Stannis will die at some point before the end of the series, but I know for a fact that Martin won’t try to somehow make everyone like him just before he dies. Martin doesn’t do that.

Martin didn’t purposefully kill Ned or Jon off because people had an emotional attachment to them. Ned died because he underestimated Cersei’s power and because Joffrey is a tool. Jon didn’t die because “Ha ha! You cared, fooled you!”. He died partly because he failed to truly understand how unpopular his decisions made him among the other NW leaders, partly because he pushed all of his loyal supporters away in an effort to be more like Ned, and partly because the other leaders didn’t truly understand what’s at stake because they still think the Others are a myth and letting the Wildlings south of the wall is foolish. In short, they die because, you know, themes matter.

Compare this with D&D, who actively try to garner up sympathy for a character just prior to killing them off. And not just sympathy from some, sympathy from everyone. They want everyone to be emotionally invested in Jaime and Myrcella’s growing father/daughter bond because they want to see everyone hurt when Myrcella dies (she’s not even dead in the books). Seriously, I don’t know how much clearer it can be that this is a form of narrative sadism. They enjoy seeing their audience hurting. When they say something that implies that Myrcella being injured wasn’t emotionally shocking enough so they had to kill her or that they wanted to rape the character that the audience was emotionally invested in, it is obvious that they want to see the audience in pain.

I mention this because it reinforces the acedia already created by their Dark and Gritty narrative. They create a world where everything is awful, so awful that a growing number of fans are actively rooting for the Others to win. People can no longer care because there is nothing redeeming or beautiful or lovely about this world. There is no hope for change, no one tries to be different, to rise above their terrible system and work for something better. It’s “There are no true knights.” Full stop. Not, “there are no true knights, except maybe there are, they just aren’t the ones you expect,” which is the world GRRM gives us.

So in this crapsack world where it is nearly impossible to care, they give you brief hints of love, of bonding between characters, only to kill those characters off immediately after you feel sympathy for them. Beat you into not caring, then get you to care a little bit, then beat you down some more. Poe’s Law would tell you that its unintentional, the result of Shock and Awe™ clickbait style show marketing aimed at getting viewers based on being Unexpected™. But the consistency with which it happens points to something much darker: a kind of sadism that delights in seeing the audience hurt.

Conclusion

Turn “what’s the new cool gadget!” into “what’s the new cool plot twist!” and you have GoT. They’re trying to sell us iPhones and LED screen TVs but on a television show. And people are too busy consuming, too busy being lulled by the “twists” and flashy sets and quasi-philosophical (but meaningless) dialogue to notice that this is taking place at the expense of the books, the world GRRM created, and the characters themselves.

D&D have successfully translated our cultural value system into a method of making a television show. Give the audience enough “plot twists” and they won’t notice or care about the damage to the source material or the characters. It doesn’t matter that the end result is horrifically racist, sexist, ableist trash. It doesn’t matter that it’s done at the expense of women and children. It doesn’t matter that it’s whorephobic and homophobic and xenophobic. All that matters is “the twist”. It’s a perfect reflection of our society’s inability to care about human suffering so long as we feel comfortable and sufficiently busy enough to keep ourselves from thinking.

Even worse, we are conditioned by our society to believe that violence and tragedy are an inevitable and unchangeable part of the human experience.

“We come to assume that these conditions—injustice, poverty, perpetual conflict—are inevitable, the only possible reality, and lose our ability to imagine that there are other ways of being, other courses of action.”—Kathleen Norris, Acedia & Me

If this is just “how the world works” according to D&D and the Westeros they’ve shown us. How are we suppose to care enough to want or even believe that it can be different? D&D give us a nihilism so acute that we literally cannot care, because there’s no reason to care. Violence is inevitable. Rape, poverty, war, injustice, suffering. It’s just “how things are” in Westeros and if you start to care about someone? Guess what, they’re dead. Fooled you.

Small wonder, then, that not even the trailer for S6 can rouse much more than a yawn from certain segments of the fandom. They’ve seen it before and they don’t care. After 5 seasons, each one progressively more Shocking,™ the audience is inured to D&D’s tactics. Weisseroff is a dark, violent place where hope, human decency, and emotional attachment are actively punished by the narrative choices of the writers and producers. The narrative focuses exclusively on “people who matter”, discouraging viewers from caring about tertiary characters or the wider effects of war on the smallfolk.

Wittingly or not, D&D have created a story that reflects the society around us, one that cares little for societal ills that do not immediately impinge upon our comfort. That seeks to lull us into a false sense of emotion via investment in what is new and exciting (e.g., narrative twists), and that actively punishes us for any real emotional attachment we have by destroying what is good and beautiful in the name of “Realism.” The only ones left after all of this will be the ones who had no emotional investment to begin with: the dudebros who are in it for “tits and dragons.”