Last Sunday’s episode of Game of Thrones put a final nail in the coffin of the Dornish subplot; an aspect of the show that even its most earnest defenders agree was a failure. Now that it’s over (I think, I was wrong once before.) it’s a good time to get into the weeds of why it was so unsuccessful. There are all the obvious issues with the plot itself, the dialogue, the casting, the direction, the costumes… but the ultimate root source of all of these is a failure of adaptation. More specifically, it’s a failure of the writers of GoT, David Benioff and Dan Weiss, to understand a fundamental feature of the source material: point of view.

The A Song of Ice and Fire (aSoIaF) series, on which GoT still claims to be based in its opening credits, is famous for George R.R. Martin’s use of what is called a “close third-person pov” structure. The story follows many principal characters. Each chapter alternates between them and is told, not only through their eyes, but also through their minds. The character’s voice are unique, and influenced by their own experiences, knowledge, and biases.

So, Sansa Stark begins the series seeing things as one would expect an eleven-year-old girl who’s been sheltered and taught idealized notions of how people in power behave would see things. As she gains experience, her commentary of the goings on in King’s Landing and the Vale become more and more insightful, and a good deal less idealized. When she becomes more wary and suspicious, people start behaving more suspiciously. Tyrion Lannister brings his vast knowledge, especially of history, to the table as he navigates through war, politics, and exile, but he also brings his misogyny, internalized ableism, and Lannister pride.

Tyrion’s biases are especially relevant here because it’s through his point of view that we first see the people who have always existed on the edge of Westeros, part of the system, and yet outside it. In many important ways, the Dornish were as much the “great other” as the Wildlings in the North, or the Free Cities across the Narrow Sea.

All Dornishmen are Snakes

I’m sorry to have to bring in the dreaded book knowledge, but it’s important that I explain what George R.R. Martin accomplished with the Dornish in the source material before I can discuss why the show failed to make the same point. Indeed, their own narrative undercuts everything that show plotline was about.

In Westerosi culture, Dorne’s separate history, cultural distinctiveness, strong sense of unity, and their determination to be politically autonomous leads them to be othered in the eyes of Westerosi. They see Dorne as an exotic place, full of violent and sexy people who look and act oddly. Put another way, they are the targets of prejudice, and what we would reasonably call “racism”. They’re certainly the subjects of a good amount of off-hand racist comments and jokes.

“Leo’s eyes were hazel, bright with wine and malice. “Your mother was a monkey from the Summer Isles. The Dornish will f-ck anything with a hole between its legs. Meaning no offense.”” -A Feast for Crows (aFfC)

“Tyrion had sent her little girl to Dorne, and Cersei had dispatched Ser Balon Swann to bring her home. All Dornishmen were snakes, and the Martells were the worst of them.” -aFfC

“Poison was for cravens, women, and Dornishmen.” -A Dance with Dragons (aDwD)a

(I should note, to avoid confusion, I’m going to refer to people who are from Westeros, but not Dornish, as “Westerosi.” This term will not include the Dornish, unless otherwise stated, even though technically, the Dornish are Westerosi.)

It’s useful when thinking about the Westerosi view of the Dornish to compare it to “orientalist” ideas in Western European thought.

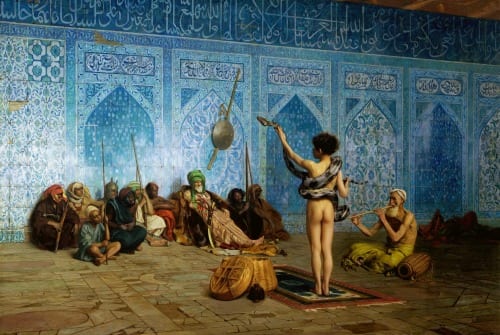

Orientalism is, strictly speaking, a nineteenth century artistic movement in Western Europe that depicted “the middle east” and points further. It’s most famous for painting of women in harem and eastern market places. These days, though, the term in most likely to be associated with the work of Edward Sa`id and his most famous book, Orientalism.

This book is a foundational text of postcolonial thought, and rather notoriously dense and difficult to get through for students in ‘Introduction to Middle Eastern Studies’ classes. What I offer is a very simplified summary of Sa`id’s ideas.

He argued that western depictions of “the orient” are, in general, inaccurate, servile, and patronizing. Even the very concept of the orient itself is inaccurate, servile, and patronizing. It conflates many complex times, places, and peoples and turns them into a “narrative of incident,” a convenient background where white people can have adventures.

This is self-serving on the part of western culture because these narrative aren’t interested in actually exploring or understanding these places. It exists to create contrast between east and west, where “the east” is irrational, weak, childlike, and feminine, and “the west” is rational, strong, developed, and masculine. It justifies western domination by implying that the western understanding of the orient is more valid than the understanding of the actual “orientals” who live there.

This plays into the Westerosi understanding of the Dornish in many ways, though one of the most obvious is the contrast between Dornish and Westerosi conceptions of Dornish “ethnic identity”. (A totally anachronistic term I only use for lack of a better one.)

Dorne has a complex history. It’s defining moment as a unified political entity was the marriage of Mors and Nymeria and the coming of the Rhoynar from Essos, but there’s a good deal more to it than that. The idea of a separate “Dornish” identity seems to have existed before then, when Dorne was inhabited by petty kingdoms of Andals and First Men. The people living in the red mountains and the deserts and river valleys beyond were certainly referred to as such when they were raiding the Reach in ancient times, and one of the titles of the Yronwood kings in the Boneway was “King of the Dornish”.

The coming of the Rhoynar had a profound cultural, legal, and political impact on Dorne. Most notably, they adopted a distinctly Rhoynar legal tradition. Still, it’s completely inaccurate to say that the Dornish are simply Rhoynar transplanted to the desert who totally overwhelmed and subjugated the indigenous Andals and First Men. That would be as inaccurate as implying that the current English identity or cultural and political system are purely the result of the Franco-Norman invasion, ignoring the Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic elements that are just as, if not more, central.

The Westerosi have made much of the “ethnic” divisions in Dorne, most famously in the Targaryen king Daeron I’s history of his conquest.

“There were three sorts of Dornishmen, the first King Daeron had observed. There were the salty Dornishmen who lived along the coasts, the sandy Dornishmen of the deserts and long river valleys, and the stony Dornishmen who made their fastnesses in the passes and heights the the Red Mountains. The salty Dornishmen had the most Rhoynar blood, the stony Dornishmen the least.

All three sorts seemed well represented in Doran’s retinue. The salty Dornshmen were lithe and dark, with smooth olive skin and long black hair streaming in the wind. The sandy Dornishmen were even darker, their faces burnt brown by the Dornish sun. They wound long bright scarfs around their helms to ward off sunstroke. The stony Dornishmen were biggest and fairest, sons of the Andals and First Men, brown-haired or blond, with faces that freckled or burned in the sun instead of browning.”

Most readers with a passing interest in the history of the Social Sciences are no doubt strongly reminded of Victorian Era pseudo-Anthropology and its preoccupation with categorizing everyone in the world into the four “races,” Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Negroid, and Amerindian.

This type of thing didn’t disappear from school textbook until well into the 20th century, but is generally considered these days to be little less than bunk. And it was an idea that interacted quite heavily with orientalism. It’s a perfect example of Western Europeans thinking they have a better understanding of “others” than the people themselves do.

It’s worth noting, of course, that the Dornish in A Song of Ice and Fire never refer to themselves using Daeron’s three categories. In fact, it’s often characters who would clearly fit into the “stony” category that are the most assertive about a “Dornish” identity.

Contrary to how the Dornish think of themselves, the Westerosi emphasize the Rhoynar aspects of Dornish culture to play up the idea that it is exotic and somehow “foreign,” rather than something that developed in Dorne with Rhoynishness as one piece of a greater cultural-political puzzle that is more than the sum of its parts.

The Dornish are Crazy

So what does this all mean for Game of Thrones, particularly as an adaptation?

This issue is that aSoIaF goes out of its way to challenge the Westerosi image of them, especially through the point of view of Dornish characters. Contrarily, the Dornish of the show simply are the orientalist stereotypes that the Westerosi believe them to be.

“The Dornish are crazy,” Bronn said in season 5. “All they want to do is fight and fuck.”

This is a rather good characterization of the stereotype in both text. Indeed in the third volume, A Storm of Swords, we first see Dornish characters (namely Prince Oberyn and Ellaria Sand,) and we do so only from the point of view of Westerosi characters. Their characterization as overly sexual and unpredictably violent is well in place. Oberyn’s mysterious darkness and reputation for poisoning and duels is his prime characterization, and Ellaria probably worships a Lyseni love goddess, at least according to the gossip that reaches Sansa.

However, by the time we meet Arianne Martell, a point of view character in A Feast for Crows, we gain an entirely different perspective on both these characters and maybe even begin to suspect that Oberyn spent the previous book playing into stereotypes deliberately in order to gain a specific political advantage and make his hosts in King’s Landing uncomfortable. Arianne’s view of her uncle doesn’t erase or deny his violent past or promiscuity, but it emphasises his devotion to his family and children, and his role as a beloved popular political figure.

The difference in Ellaria as soon as she crosses the mountains is even more striking. The woman who was framed as the classic dark, seductive foreign woman who uses her sexuality in a magical way, probably to control men for her own purposes, is revealed to be rather conventionally feminine and focused primarily on her role as a mother. Rather than trying to manipulate people, her main wish is to break the cycle of violence in order to keep her children safe.

Contrast this to the way the Dornish are played throughout their run on Game of Thrones. These stereotypical aspects were not only played straight and presented without challenge, but also dialed up to eleven.

The first Dornish we meet are a monolith of dark, broody men who are identically dressed. The sole speaker in the group introduces us to the cartoon accent that will be used for all Dornish characters for the next four years.

This scene is short and relatively unimportant, but it’s very telling as to how simplified and exoticised Dornishness will be, even compared to the Daeron I’s racist ethnography. For one thing, they’re all men, eliminating the important role that women have in politics in Dorne, another thing that Westerosi think is very unusual, and probably dangerous. And for another thing, there is none of that diversity of appearance that allowed Daeron’s ethnography to begin with. Here, every Dornishman is the same, and he has the same opinion about everything.

Then we meet Oberyn and Ellaria and…. they’re in a brothel. As far as anyone can tell, this is where they’ll live for the duration of their stay.

Now, the Oberyn of the books series is canonically bisexual and his relationship with Ellaria is implied to not be entirely monogamous. While it’s true that the Dorne of the books is notable for its permissive attitude to sex in general and homosexuality in particular, I don’t think it’s uncontroversial to say that the emphasis GoT placed on these elements goes beyond what the source material indicated.

There’s no clearer indication of this than that first scene, where the pair were apparently so overcome with the need for sex that they ditched the king and headed straight for the brothel for group sex. And this emphasis on the salaciousness of their sex life does not stop for the entirety of the season. For Ellaria especially, there seems to be nothing in life but having sex, and there’s little indication that she and Oberyn have anything in common other than the fact that they enjoy having sex in the same room.

An obsession with sex is a common orientalist trope. Concubinage and the harem especially terrified and fascinated puritanical western minds, though their views of both of those things bore little resemblance to reality.

In these conceptions of oriental sex, female homosexuality is omnipresent, if always implied, and it’s used as a way to characterize orientals as barely in control of their own sexual impulses. So while there’s little implied about Oberyn and Ellaria in season 4, their frequent scenes, with the set decorated with the bodies of sex workers of both genders, serve the very same function. And they contrast very tellingly with, for example, Cersei and Jaime’s need to keep their relationship secret, or Tyrion’s chaste marriage to Sansa.

The other half of the Dornish coin in the opening scene with Oberyn and Ellaria comes later on, when they overhear a man in the other room singing a pro-Lannister song. In retaliation, Oberyn stabs the man through the wrist, while his lover watches, clearly aroused.

This violence isn’t the controlled, calculated violence that is wielded for political or military ends by other characters within the show; it’s impulsive and irrational. Oberyn can’t help himself, it seems.

The prince, however, did receive a few humanizing and complicating moments in the episodes before his death. These were the moments that made him a successful character. But Oberyn’s success was perhaps the downfall of the show’s presentation of Dorne, because the following season doubled down on the uncontrolled sex and violence, but was unable to recreate the charisma that made it bearable.

Weak Men Will Never Rule Dorne

In the fifth season, the emphasis in Dorne shifted to the bereaved Ellaria Sand and Oberyn’s adult daughters. And their need for revenge.

This need put the women in conflict with Oberyn’s brother Doran. The narrative attempted to frame this as somehow a victory for women over restrictive patriarchal control, but in the end, it was all a rather textbook example of Sa`id’s Narrative of Incident. The truly important conflict of the storyline was not the one within the Dornish royal family, it was the peril that Jaime Lannister, and his daughter Myrcella, were placed in in this strange and mysterious land.

Indeed, any even cursory consideration of the motivations and actions of the Dornish characters reveals how little sense they make. Myrcella as a target for Ellaria and the Sand Snakes revenge makes no sense. Her misplaced anger towards Prince Doran for not sharing her impulse makes even less, but that hardly matters because Ellaria is not a rational actor, because the orient is a place that doesn’t allow for rational action.

In contrast to the directness of western political violence, where knights face each other in duels governed by well understood and rigidly adhered to rules, oriental political violence is always hidden. It’s characterized by poison and brothers stabbing each other in the back. There are endless betrayals and lies. No one can be trusted, and no one ever tells the whole truth. And in the end, no one survives. The very impossibility of navigating such despotic harem politics is the point. It is meant to be impossible to survive or to change. Neither Doran nor Jaime’s good intentions could survive Ellaria’s need for revenge. Indeed, not even Ellaria could survive Ellaria’s need for revenge, because there was no reason to it. She was no more in control of her impulse toward violence in seasons 5, 6, and 7 than she was in control of her need for sex in season 4.

Again, the book series presents us with a Dornish court with a reputation for poison and intrigue, and then challenges this image through its Dornish point of view characters. The intrigue and conspiracy may still be there, but it’s contextualized entirely by Arianne and Quentyn’s love of family and need to do their duty. Importantly, it’s a context that has everything to do with them and with Dorne, and with these two characters as political agents.

There was the barest hint of this kind of agency in season 4, when Oberyn’s revenge was framed as a response to familial love for his sister and the injustice of her death. But as soon as the scaffold of directly adapting material from A Song of Ice and Fire was removed in season 5, all this context that would have made the actions of Dornish characters comprehensible or relatable disappeared. Their actions became things that happened to other, more favored characters.

The Dornish were not truly characters on Game of Thrones; they have been much more like forces of nature. Beyond reason and understanding.

Dorne itself, as a place, was poorly defined. It seemed entirely uninhabited except for a few guards who may as well be mannequins, and consisted of nothing but a little patch of desert. It didn’t have a history of its own, or any people to have opinions about the violent overthrow of their monarch. Such considerations were never deemed to be important. As in 19th century Western Europe, the only importance that the orient (Dorne) can have is in what it teaches those who observe it.