Is it cheating to bring a character back from the dead?

I don’t remember reading “The White Rider” for the first time. I’m not sure there was ever a time when I was working under the assumption that Gandalf was fully, irrevocably gone. And at this point it’s hard to even imagine a story in which he doesn’t come back, in which the fellowship struggles forward as they were, imperfect and alone.

And it doesn’t feel like cheating to me: not for any plot or mythos specific reason, but simply because it’s good for the story. Gandalf is a wonderful, vibrant character from his first appearance. He’s funny, charming, wise, and sometimes hasty. He’s fallible and intensely aware of it. He always feels like such a human character, and it’s easy to get lulled into a false sense of security that he’s just a wise, talented old man in a pointy hat. But he’s not. Gandalf is old—nearly incomprehensibly old by human standards. He lived with the Valar, he walked Middle-earth for ages. There are depths to Gandalf—it’s no wonder he and Treebeard got on so splendidly. And one of the great treats of “The White Rider” is catching of glimpse of these depths, as buried facets of Gandalf simmer to the surface.

The White Rider

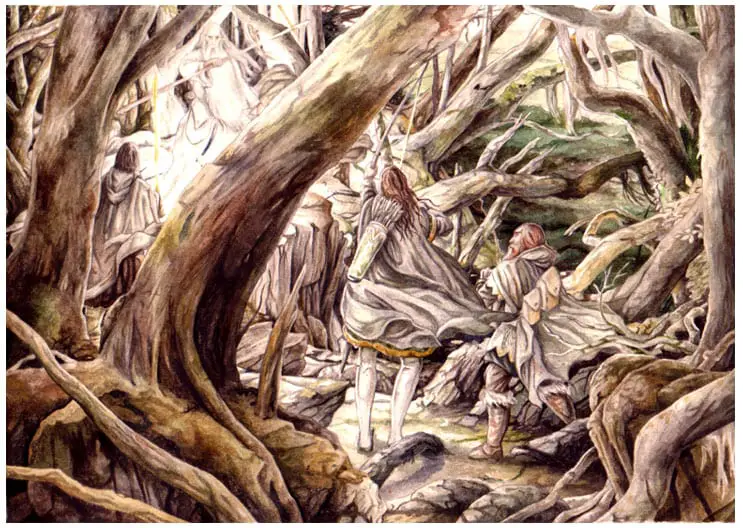

Gandalf the White makes his first appearance as a threat. Legolas spies him skulking through the woods, a hooded figure in white. He’s meant to be ominous:

At that moment the old man quickened his pace and came with surprising speed to the foot of the rock-wall. Then suddenly he looked up, while they stood motionless looking down. There was no sound.

It’s a creepy scene. The figure’s speed changes jarringly, the silence draws out the tension. When our trio react with fear, they are stricken by an inability to move or speak. The man will not identify himself, and insists the others talk about themselves. At one point he laughs “long and softly” which is a horrifying way to describe a laugh? And even after everyone recognizes this figure, he only remembers his name when Aragorn speaks it to him.

A lot of this is designed to ratchet up tension for first time readers. Most of the trio – especially Gimli – is convinced that this is an impending Saruman attack, so the ominous underlay makes perfect sense. But it also has the interesting side effect of forefronting danger as a key aspect of who Gandalf is. Gandalf himself makes this explicit later:

“I thought Fangorn was dangerous.”

“Dangerous!” cried Gandalf. “And so am I, very dangerous, more dangerous than anything you will ever meet, unless you are brought alive before the seat of the Dark Lord. And Aragorn is dangerous, and Legolas is dangerous. You are beset with dangers, Gimli, son of Glóin; for you are dangerous yourself, in your own fashion.”

Gandalf has always been dangerous. But underlining his return with a sense of danger and strangeness makes the reader immediately aware that something has changed. Gandalf has returned, but he’s not quite who he had been.

The Wizard and the Balrog

And, to be fair, who would expect him to be? Gandalf has had a *rough* couple of weeks. After taking a tandem dive off Khazad-dûm with a fire demon, he plunged into an icy pool and then had a forty-eight-hour battle royale on a frozen mountaintop. When he cast the balrog down, he broke the mountain. This is a nice taste of Gandalf’s recent experiences:

“Far below the deepest delvings of the dwarves, the world is gnawed by nameless things. Even Sauron knows them not. They are older than he. Now I have walked there, but I will bring no report to darken the light of day. In that despair my enemy was my only hope.”

Yikes, Gandalf! That’s rough, buddy! The degree to which this was a traumatizing experience can be seen in his description of the battle, as he slips in an out of first person:

“But what would they say in song? Those that looked up from afar thought that the mountain was crowned with storm. Thunder they heard, and lightning, they said, smote upon Celebdil, and leaped back broken into tongues of fire. Is not that enough? A great smoke rose about us, vapor and steam. Ice fell like rain. I threw down my enemy, and he fell from the high place and broke the mountainside where he smote it in his ruin.”

It’s interesting how Gandalf tells his story, and how he abstracts himself until the moment of victory. Before that, everything is told from the perspective of a hypothetical third party or in the passive tense. It creates the sense that Gandalf only partially relates to that Gandalf on the mountaintop, and creates a distance between past and present identity. And that raises an important question: who is Gandalf the White?

Gandalf the White

“Then darkness came to me and I strayed out of thought and time, and I wandered far on roads that I will not tell.”

We get two different glimpses of Gandalf in the course of “The White Rider.” The first comes from Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli. When Aragorn first hears the hooded figure laugh—before he knows his identity—he describes the sound as giving him a “strange, cold thrill” comparable to “the sudden bite of keen air, or the slap of a cold rain that wakes an uneasy sleeper.” After that, nearly every description of Gandalf features sunlight.

The first description given to him after being revealed states that his hair “was white as snow in the sunshine, gleaming white was his robe, his eyes under deep brows were bright, like rays of the sun; power was in his hand.” His laugh, no longer long and soft, is “kindly as a gleam of sunshine.” The Trio looks over to see another gleam of sun, this time filtering through the clouds and filling Gandalf’s hands with light “as a cup is with water.” At one point he looks straight into the sun; at another he recalls Gwaihir’s shock that Gandalf’s body was so light that “the Sun shines through you.”

In this line of thinking we get the easiest interpretation of Gandalf’s ordeals: it was a process of purification. Gandalf as always been associated with fire. He bears Narya, the ring of fire. Tolkien described him as inherently opposing “the fire that devours and wastes with the fire that kindles… his joy, and his swift wrath, were veiled in garments grey as ash, so that only those that knew him well glimpsed the flame that was within.”

But instead of a buried, turbulent flame, Gandalf’s ordeals have distilled him into purer sunlight, clearer and more assured. All of this also takes on more poignant tone, as Gandalf—when first sent as an emissary to Middle-earth by Manwë—attempted to decline, saying he was too fearful to go. It happens nearly entirely off-page, but it’s a lovely character arc. His battle with the balrog has concentrated him, illuminating the aspects that always lay underneath.

The Turn of the Tide

That’s not the whole story, though. Gandalf is more powerful than he was, and more self-assured. But there is a sense that he still feels somewhat powerless:

There I lay staring upward, while the stars wheeled over, and each day was as long as a life-age of the earth. Faint to my ears came the gathered rumor of all the lands: the springing and the dying, the song and the weeping, and the slow everlasting groan of overburdened stone.

And later:

I have forgotten much that I thought I knew, and learned again much that I had forgotten. I can see many things far off, but many things that are close at hand I cannot see.

Gandalf’s knowledge feels greater than it ever was; he can sense Saruman’s thoughts and sense Sauron’s purpose. He can hear the “rumor of the lands” and glimpse far-off things. But knowledge never brings him a sense of omnipotence or control. The “rumor” he hears is chaotic and contradictory, filled with slow, large-scale trends but lacking focus. His knowledge reaches to the “far-off” but not the close up. There is a permeating sense that Gandalf knows so much, but not enough.

It’s a double thematic bonus for Tolkien. It gives Gandalf limitations, so his assertion that “much will be destroyed and all may be lost” and that “I am Gandalf, Gandalf the White, but Black is mightier still” does ring true. And more importantly, it implicitly highlights the importance of free will and individual action in the narrative. Gandalf can know so much, but still not that Sam would accompany Frodo, that Merry and Pippin would be cast into Treebeard’s path, or any of the other “small stones that start an avalanche in the mountains.” All power in Tolkien’s universe must be limited. There are too many factors at play.

[Side note: This also places a nice capstone on Aragorn’s arc. On several occasions he has wished for more information in order to make a decision; it’s suggested here that knowledge does not necessarily come accompanied by the comfort of certitude]

Empathy and the Enemy

Despite all of these character beats from Gandalf, I can imagine complaints from those, ermm, less sympathetic to Tolkien’s style. Gandalf’s massive Balrog battle happens off-page, and is quickly summarized in about two paragraphs. And before we even get to it, we get pages of speechifying. It’s understandable that some people may grumble about trading a mountain battle for a mountain of exposition.

I think it’s good exposition though, and rather needed. Sauron and Saruman have been such distant, obscure threats for most of the story. And that’s been fine: so much of the drama of The Fellowship of the Ring was predicated on that distance and obscurity, and the real conflict happened largely within our characters. But at the same time, it’s nice to get some insight from the newly-insightful Gandalf.

[Sauron] assumes that we were all going to Minas Tirith; for that is what he would himself have done in our place… Indeed, he is in great fear, not knowing what mighty one may suddenly appear, wielding the Ring, and assailing him with war, seeking to cast him down and take his place. That we should wish to cast him down and have no one in his place is not a thought that occurs to his mind. That we should try to destroy the Ring itself has not yet entered his darkest dream.

It is so satisfying to me that Sauron’s—and Saruman’s—downfall boil down to a lack of empathy. The only reason that anything in Lord of the Rings works is because the bad guys simply lack the imagination to consider that the world is different from what they imagined it to be. Sauron’s world is one of conflict, strife, power. That’s understandable, given his history. It’s also, in part, incorrect. Saruman is in the same position:

There is much that he does not know…. His thought is ever on the Ring. Was it present in the battle? Was it found? What if Théoden, Lord of the Mark, should come by it and learn of its power? That is the danger that he sees, and he has fled back to Isengard to double and treble the assault upon Rohan. And all that time there is another danger, close at hand, which he does not see, busy with his fiery thoughts. He has forgotten Treebeard.

It’s a lovely little twist: Gandalf and Aragorn stress throughout the first half of The Two Towers concerning the things that they could not possibly know. They are acutely aware of them. Sauron and Saruman fear what they don’t know as well, but they also assume that they know what to fear. Evil fails in Middle-earth due to a failure of imagination and a lack of empathy. This revelation pairs so well with the newly-minted Gandalf the White’s thoughts and troubles (and Aragorn’s up to this point) that this chapter provides a good argument that Tolkien had a very strong sense of thematic cohesion in his work, and that these themes work on a multitude of levels.

Final Comments

- FIRST THINGS FIRST: I honestly can’t believe Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas, aren’t freaking out over losing Éomer’s horses. It’s been a couple of hours and he basically said that his life relied on them returning them safely. They are so wrapped up in their new mystery-solving club that they don’t even pay poor Éomer a second thought.

- Gandalf describes Treebeard as “the oldest living thing that still walks beneath the Sun upon this Middle-earth.” A million continuity purists and Tom Bombadil fans cry out in anguish.

- As a kid, it bothered me a bit when Aslan rose from the dead in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. I’m sympathetic to people being bothered in a similar capacity by Gandalf’s return. But at the same time, it feels very different to me. Aslan’s resurrection is unavoidably allegorical; Gandalf’s is not. Tolkien’s worldbuilding is wonky and multifaceted enough that very few things —even those that are obviously influenced by Christianity—feel rigidly Christian.

- This is a good chapter for Gimli, who continues to be a great character. He’s moody and emotional but always endearing. I very much enjoyed his unbridled faith in Aragorn’s investigative abilities, his shame over failing to recognize Gandalf (and trying to hit in the head with an axe) and his teasing of Legolas. My favorite, though, has to be his dramatic overreaction to thinking Galadriel failed to send him a message. Legolas point out that the messages were… ominous. “Would you have her speak openly to you of your death?” he asks. “Yes,” says Gimli, “if she had nought else to say.” I believe this is what kids these days call being EXTRA.

- Legolas does well for himself too: he calls Aragorn and Gimli “children” and teases Merry and Pippin for celebrating their escape by immediately sitting down for a snack.

- “What? In riddles?” said Gandalf. “No. For I was talking aloud to myself. A habit of the old: they choose the wisest person present to speak to; the long explanations needed by the young are wearying.”

“I am no longer young even in the reckoning of men of the Ancient Houses,” said Aragorn.

I enjoy how petulant Aragorn sounds here. He sounds like a teenager insisting he’s an adult. - Prose Prize: “The grey figure of the Man, Aragorn son of Arathorn, was tall, and stern as stone, his hand upon the hilt of his sword; he looked as if some kind out of the mists of the sea had stepped upon the shores of lesser men. Before him stooped the old figure, white, shining now as if with some light kindled within, bent, laden with years, but holding a power beyond the strength of kings.”

- Contemporary to this chapter: It is also March in Middle-earth. Gandalf makes his reappearance on March 1st, the second day of the Entmoot. Meanwhile, over the east, Frodo and Sam are entering the Dead Marshes.

- It’s been about six weeks since Gandalf’s disappearance – he fell at the Bridge of Khazad-dûm on January 15th. His battle with the Balrog on Zirak-Zigil was on January 23-25, which means poor Gandalf spent a solid week in the pits of the earth. After the Balrog’s death he lied on the mountaintop for about three weeks, awakening in mid-February while Frodo was looking into the Mirror of Galadriel. He only missed the Company in Lórien by a day.

- Éowyn countdown: NEXT CHAPTER. Mark your calendars Tolkienites, our favorite shield maiden makes her debut on March 29th.

Art Credits: In order of appearance, images are courtesy of rysowAnia, Laura Tolton, kinko white, Peter Xavier Price, and Ted Nasmith.