As we’ve made our way further through The Lord of the Rings, I’ve become fond (too fond?) of talking about pivot points: places where the narratives shifts and reorients itself. I’m going to risk talking about it one more time, at the risk of getting repetitive. And that’s simply because “The Taming of Sméagol” does it in such an interesting, masterful way.

Tolkien was faced with a difficult task here. He was required to zoom back in time to characters that hadn’t appeared for – in my edition – 243 pages. He was required to shift a narrative from a collection of uber-competent travelers (including a lost king, a demigod wizard, and a near-immortal tree shepherd) to two hobbits wandering around in the hills, and Gollum, who in lesser hands could have turned into a traumatized, shrieking frog. And he was required to shift from a narrative that recently featured night battles, tree attacks, wizard showdowns, and a vocal cameo by Sauron himself, to one that features… lots of walking.

In short, it’s something that could very easily have gone very wrong. But “The Taming of Sméagol” is a well-crafted reorientation, one that manages to tie the narrative back to Book III, but also to establish it on firm footing, heading towards something new.

Reaching Forward, Reaching Back

From the start, “The Taming of Sméagol” both looks back towards the past and ahead towards the future.

It starts right at the beginning. We drop immediately into dialogue, with Sam Gamgee saying “Well, master, we’re in a fix and no mistake.” It’s jolting at first: Sam’s one of the only lower-class characters in the book, and his dialect simply sounds different than the tones we’ve heard in the pages before. It sounds earthy, local, specific. We’ve been dealing with things on the scale of the whole of Middle-earth, with wizard and kings (and lorldly hobbits). But at the same time, there’s a nice thread of thematic continuity as well. “The Palantír” ended on a note of barely-managed chaos, characters fleeing off into uncertainty in the middle of the night. While Sam’s opening line sounds different, it’s also stating a fact that carries over nicely from Book III.

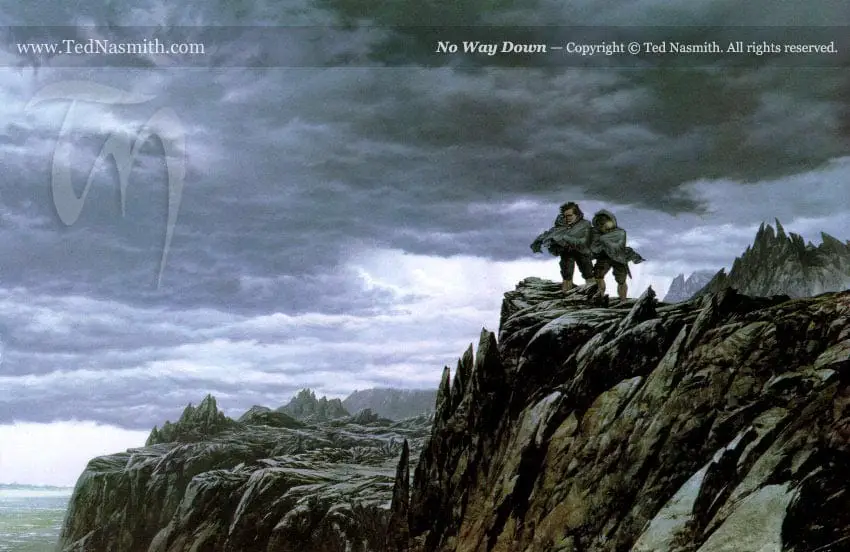

The same could be said for Frodo and Sam meandering through Emyn Muil, struggling to find a way down. This, simply put, would never have happened in Book III. Legolas would have leaped down gracefully with his eyes closed, laughing at the other two all the way. Aragorn would have mapped out a clear, feasible route down. Gimli would have grumbled; he also would have been fine. Those three essentially sprinted for an entire chapter, covering obscene amounts of land. Frodo and Sam wander around, never getting far from where they started. But at the same time, once again, there’s some continuity. It can be see in Frodo’s rather-morose speech about heading towards Mordor:

“It’s my doom, I think, to go to that Shadow yonder, so that a way will be found. But will good or evil show it to me? What hope we had was in speed. Delay plays into the Enemy’s hands – and here I am: delayed. Is it the will of the Dark Tower that steers us? All my choices have proved ill. I should have left the Company long before, and come down from the North, east of the River and of the Emyn Muil, and so over the hard of Battle Plain to the passes of Mordor. But now it isn’t possible for you and me to find a way back, and the Orcs are prowling on the east bank. Every day that passes is a precious day lost. I am tired, Sam. I don’t know what is to be done.”

Not only does this speech set the emotional tone for the chapter, and engage the reader’s in Frodo’s already-tired mental state, but it also cleverly ties together Frodo and Aragorn. In the first chapter of Book III, Aragorn frets that “all I have done day has gone amiss,” a nice precursors for Frodo’s concern here that all of his choices have proven ill. It’s a nice mirroring effect, to have the two protagonists of these books fret about the same things in parallel, unsure of what to do when facing a critical choice without sufficient information.

Questions of Danger, Questions of Scope

Tolkien pulls the same trick in his treatment of danger. The start of the chapter, as the hobbits are trying to get down from the hills, suggests that the dangers they face will be consistent with those of Book III. Just as “The Palantír” ended with the fly-over of a Black Rider, the first major threat of “The Taming of Sméagol” arises when a Black Rider flies by Frodo. It’s a nice little tying-together of the two books with a common threat.

But after that, things begin to shift. At first, this happens in a very literal way: the danger simply moves away from Frodo and Sam.

“The skirts of the storm were lifting, ragged and wet, and the main battle had passed to spread its great wings over the Emyn Muil, upon which the dark thought of Sauron brooded for a while. Thence it turned, smiting the vale of Anduin with hail and lightning, and casting its shadow upon Minas Tirith with threat of war. Then, lowering in the mountains, and gathering its great spires, it rolled on slowly over Gondor and the skirts of Rohan, until far away the Riders on the plain saw its black towers moving behind the sun, as they rose into the West. But here, over the desert and reeking marshes the deep blue sky of evening opened once more, and a few pallid stars appeared, like small white holes in the canopy above the crescent moon.”

Sending the storm from Emyn Muil to Rohan gives a nice physical link between the two stories, and then allows Book IV to move on. Because nearly as soon as the storm passes overhead, Frodo and Sam make it down the cliff and face a threat more immediate and personal than a Black Rider or Mordor. Gollum is such a tremendous narrative force in The Lord of the Rings, and his arrival – after literal books’ worth of lurking – fundamentally changes the story. We’ve talked here before about how much of the danger in The Fellowship of the Ring was internal: Sauron was distant, abstract; the Ring and temptation surrounding it was omnipresent. That had shifted somewhat in the first half of The Two Towers. While moral uprightness and personal decision-making remains paramount (Théoden is a good example), the obvious, external threats were much more real and present.

As we settle into Book IV, the pendulum is going to swing the other way. While there are certainly going to be a slew of external problems, the core of this book is internal and inter-personal. And that brings us to Gollum (and Sméagol).

Gollum

Just as the rest of this chapter works by looking both forward and back, the arrival of Gollum does the same thing. He’s been in the narrative for ages, either skulking behind the Fellowship, or appearing in the stories they tell in Hobbiton or Rivendell. And as soon as he appears, to Frodo – who’s already filled with anxiety – he’s the potential shape of things to come. It’s apparent on several occasions, but most clearly when Sméagol, desperate to free himself from the Elven rope that’s hurting him, swears to “serve the master of the Precious.” (Frodo, we see here, has never been to law school).

Frodo drew himself up, and again Sam was startled by his words and his stern voice. “On the Precious? How dare you. Think! One Ring to rule them all and in the Darkness bind them.”

“Would you commit your promise to that, Sméagol? It will hold you. But it is more treacherous than you are. It may twist your words.”

“… Sméagol will swear never, never, to let Him have it. Never! Sméagol will save it. But he must swear on the Precious.”

“No! Not on it,” said Frodo, looking down at him with stern pity. “All you wish is to see it and touch it, if you can, though you know it would drive you mad. Not on it. Swear by it, if you will. For you know where it is. Yes, you know, Sméagol. It is before you.”

For a moment it appeared to Sam that is master had grown and Gollum had shrunk: a tall, stern shadow, a mighty lord who hid his brightness in a grey cloud, and at his feet a little whining dog. Yet the two were in some way akin and not alien: they could reach one another’s minds.”

The danger and tragedy of the book comes to the forefront immediately: Gollum is the biggest, most imminent threat to their safety. It’s hard to argue with that. But he’s also a tragedy, and a tragedy that’s clearly, bluntly linked to Frodo’s eventual path and fate. It’s a tricky line that Tolkien walks, and I think he nearly always manages to walk it well. Gollum is a sign, a symbol, but he’s also always real: dangerous, pathetic, fraught.

Sméagol

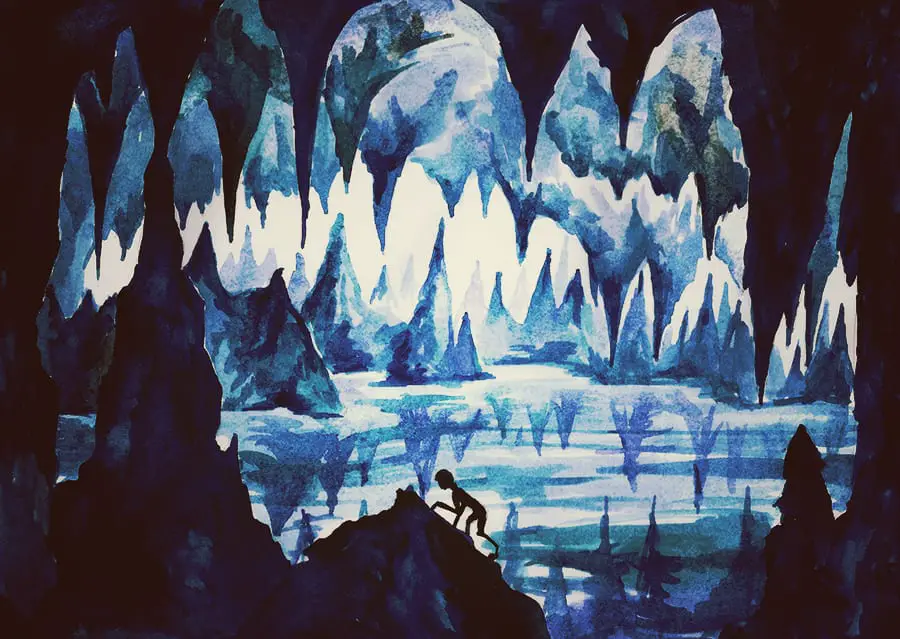

It’s interesting how Tolkien describes Gollum and Sméagol: in his first appearance he feels very foreign and unknowable, crawling face-first down a stone wall. He’s likened to an insect and then a spider, his speech patterns are filled with gulps, hisses, and sibilants. He’s strange, distant, threatening and unknowable. But as the chapter progresses, Sméagol is reeled in closer, and his depth and complexity is revealed through language. Here’s his first line of dialogue:

“Ach, sss! Cautious, my precious! More haste less speed. We musstn’t rissk our neck, musst we, precious? No, precious – gollum.” He lifted his head again and blinked at the moon. “We hate it,” he hissed. “Nassty, nassty, shivery light it is – sss – it spies on us precious – it hurts our eyes.”

It’s all hisses and k’s and t’s. And it’s interesting…the first time that Mordor is brought up in conversation, Gollum slips right into the same speech pattern, including the starting “ach, sss!” His description of his time there (“ashes, ashes, and dust, and thirst there is: and pits, pits, pits and Orcs”) is filled with the same sounds.

When Sméagol starts to emerge though, at least a version of Sméagol, all of that begins to change.

“Yess. Yess. No!” shrieked Gollum. “Once, by accident it was, wasn’t it, precious? Yes, by accident. But we won’t go back, no, no!” Then suddenly his voice and language changed, and he sobbed in his throat, and spoke but not to them. “Leave me alone, gollum. You hurt me. O my poor hands, gollum. I, we, I don’t want to come back. I can’t find it. I am tired. I, we can’t find it, gollum, gollum, no, nowhere. They’re always awake. Dwarves, Men, and Elves, terrible Elves with bright eyes. I can’t find it.”

As soon as his voice changes, as Tolkien himself writes, so does the language: even beyond the slide into first-person, it feels fuller, more diverse. The only s-sounds that arise refer to his tortured hands, and the dwarves and elves who have terrified him in the past. The rest is a filled with longer vowel sounds, and a mix of l’s, r’s, and m’s. Gollum’s speech patterns, from the start, are tied to Mordor and to torture, as if they’ve been piled on top of him so heavily that the edifice of Sméagol that had lain beneath simply collapsed. He still exists somewhat, and Frodo tries to drag it out by repeatedly using his name. And that brings us to the saddest line in a chapter full of sad lines:

“Don’t ask Sméagol. Poor, poor, Sméagol, he went away long ago. They took his Precious, and he’s lost.”

Sméagol is right and he’s wrong. There does seem to be a part of him that remains, and much of Book IV is going to be exploring that, seeing if he can be cultivated and drawn out. I think throughout, there’s a hope of that. But there’s an element of doubt in that, right from the start. Even at his most “well-behaved,” there’s something still missing from Sméagol. He’s described as a “little whining dog” rather than a person. He’s constantly on edge, twitching or jumping away from unexpected actions and sounds. He’s overly-eager, laughing hysterically and jokes and falling down into a whimpering depression at the slightest suggestion of displeasure from Frodo.

Even at his “best,” Sméagol is clearly and deeply traumatized, sensitive, scared, and overly-performative as an attempt to cover it up. It’s tragic in its own right, and can be hard to read. But it takes on a double layer of tragedy, because it sets up Frodo’s future into two unpleasant paths. He can follow Gollum, and fall into the power of the Ring. But even if he follows Sméagol, and manages to hold onto himself, there’s the lingering implication that there’s a part of him that will be gone.

Final Points

- In a neat little point that I never noticed before, Gollum’s arrival also foreshadows Shelob, as he’s likened to a spider and his grip on Sam’s neck is described as a “tightening cord.”

- I can’t reiterate enough how important I think Gollum / Sméagol is to The Lord of the Rings. With a few possible exceptions that I’d *maybe* consider, I’d argue that he’s the most important character in terms of shaping the story into what it is, and what makes it unique.

- This poor essay was getting long enough already, so I didn’t mention it in depth. But I’m really interested to look at the dynamic between Sam and Gollum going forward. Sam is such a sweetheart overall, and I love him dearly, but he’s often rather mean to Gollum. But it’s fitting for his character. And from what I remember, it creates a really interesting relationship going forward.

- Also, one of my favorite throw-away moments in the series is when Sam is reluctant to climb down the cliff-face. He moans about it for a while then just resignedly sits down, swings over the edge, and tries to climb down blindly without a rope. OH, SAM.

- Frodo’s little speech near the beginning is intriguing not only for its parallel to Aragorn, but also because it highlights how emotionally exhausted Frodo already is, and how important the question of free will and choice will be to this narrative.

- Looking back on my first paragraph – I guess Gollum does kinda come across as traumatized, shrieking frog? But, like, in a thoughtful way.

- I am not a linguist in any form, shape, or fashion. Most of what I wrote here was just my own observations. If I am glaringly wrong about it, and you’d like to school me in linguistics, please do go for it.

- Prose Prize: I am a big fan of the description of that storm. ““The skirts of the storm were lifting, ragged and wet, and the main battle had passed to spread its great wings over the Emyn Muil, upon which the dark thought of Sauron brooded for a while. Thence it turned, smiting the vale of Anduin with hail and lightning, and casting its shadow upon Minas Tirith with threat of war. Then, lowering in the mountains, and gathering its great spires, it rolled on slowly over Gondor and the skirts of Rohan, until far away the Riders on the plain saw its black towers moving behind the sun, as they rose into the West. But here, over the desert and reeking marshes the deep blue sky of evening opened once more, and a few pallid stars appeared, like small white holes in the canopy above the crescent moon.” If Tolkien ever mentions mountains and stars in the same passage, I probably gasped a little when reading it, thinking how pretty it was.

- Contemporary to this chapter: The first three and a half chapters (!!) of Book III are covered in the first paragraph of Book IV, as Frodo and Sam wander around and try to find their way out of Emyn Muil. It does make sense, given that Book IV stretches much further into the narrative than Book III. But it still makes me laugh.