In October of 2014, Gillian Flynn fired back regarding criticisms about Amy Dunne’s likability in Gone Girl by saying, “If a male author writes a nasty male character he’s an anti-hero, but if a woman does it it’s anti-feminist.”

Women have always been pigeonholed in film as either one thing or the other. They are never allowed to explore the grey space between the black and white. They’re denied the right to be the complex, messy, and diverse group of people that they are. They always have to be pretty or likable. The concept of an ‘anti-hero’ is foreign to leading female characters. Yet, it is the type of character and journey that exists for and applauded of the most popular male characters in film.

Yet, David Fincher’s Gone Girl, an adaptation of the Gillian Flynn novel of the same name, masterfully uses and exploits the archetypes women have been sectioned into. In doing so, the film articulately critiques these misogynistic molds by breaking down all barriers and presenting the sociopathic Amy Dunne as she is. She’s multidimensional, complex, harsh, riveting, haunting, and frankly, unlikable. Fincher and Flynn give Amy the anti-hero arc and character study monopolized by men in film. Never shying away from who she is while still painting her as a three dimensional human being that we can empathize with and to do so while being herself.

Amy’s allowed to be wholly female, a product of her gender and her society. She is a response to the female experience and the terrifying and captivating monster audiences can be both drawn to and fearful of. Gone Girlbreaks the mold of female characters in film being nothing more than stereotypes meant to encapsulate the female experience as a whole. It gives Amy the space to exist as men have on screen for all of film history, as a fully formed, individual character, a human being. (However fucked up of a human being that is).

The genius and attraction of a character like Amy Dunne is that the audience goes on the journey with her. They understand how she got to the place we find her in in the film, and at the end of it all are frightened by the empathy that has arisen within us. And it is definitely no mistake or accident that she is a woman. She’s shaped by the female experience as is the audience’s interpretation of her.

While most people leaving the theater wouldn’t deny Amy has some form of psychosis, there’s still a gender divide while watching the film that exists out of experience. Women might not identify with Amy’s violence but they identify with her emotions and her experience in the world. They have felt it too; her anger, frustration, and sadness that the man she married is not willing to be the person he promised her he would be. The betrayal. The frustration that despite his unwillingness to keep up his side of the charade, he was under the impression that she should.

This misogynistic man, his position as writer for a ‘man’s magazine’ (Amy asks if the title deems him “an expert on being man”) is the “Good Guy” character trope to a tee. Or so he thinks. Women hate him for it and the film condemns him for it. He’s the type of man who is “nice” and thus expects something in return. The man who feels entitled to rewards for good behavior. Neither Amy or Nick are good people, “that’s marriage” after all. But Amy’s anti-hero arc in the story comes from female experience and is product of her environment in the visceral way that only true antiheroes arcs are.

What Makes an Anti-Hero

While Gone Girl is primarily an exploration of marriage and partnerships and what lies underneath all that, the underbelly is what makes Amy the perfect anti-hero. Within that framing comes exploration of gendered structures and expectations, thwarting preconceived ideas and stereotypes. Amy is never reduced to one thing; she’s juxtaposed with a myriad of the other women who dominate Nick’s life. Women who he refuses to listen to but who work to highlight who he truly is, just as he helps highlight who Amy is. Amy isn’t a pure evil MRA fantasy as many would cite, but is a product of her childhood and her gendered life experience.

The Sympathetic Backstory

From the subtlety and calcuolatory aspect of her nature as an “only child,” Amy felt the need to constantly perform and meet standards. She’s the peg that her parents hung all their hopes and dreams upon.

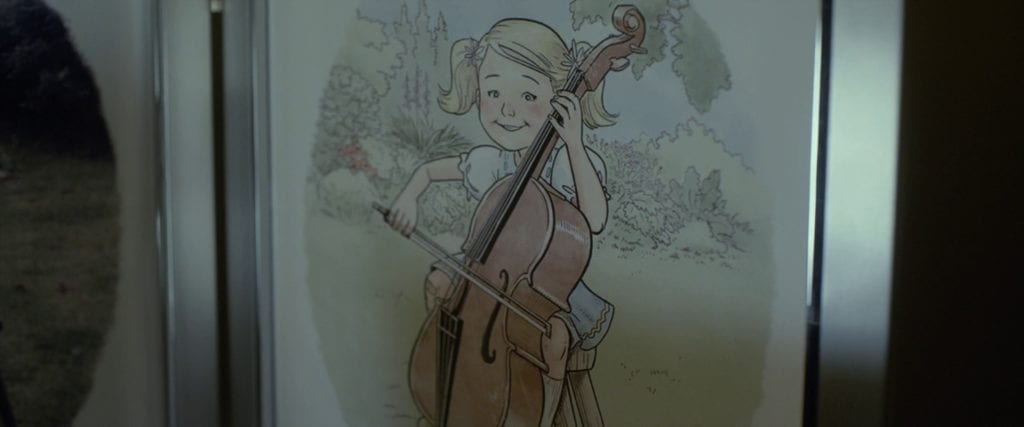

Her parents amplified that to the maximum by creating the ideal version of herself in book form (“Amazing Amy”). Thus ensuring that she would never be able to live up to the achievements of her fictional counterpart. Amy mentions it in the novel of the same name, saying,

“I’ve never been more to them than a symbol anyway, the walking ideal. Amazing Amy in the flesh. Don’t screw up, you are Amazing Amy. Our only one. There is an unfair responsibility that comes with being an only child – you grow up knowing you aren’t allowed to disappoint, you aren’t even allowed to die. There isn’t a replacement toddling around; you’re it. It makes you desperate to be flawless, and it makes you drunk with the power. In such ways are despots made.” Gone Girl, Gillian Flynn

From that relationship with her parents and “Amazing Amy” alone comes her manic need to achieve perfection. It’s an obsessiveness, a need to assert the control she was never allowed. It led her to feel the need to concoct her own story that would finally allow her to achieve everything and more than “Amazing Amy” did. She wove a greater and grander tale than the professional writers that tried to dictate her life and Nick ever could. All of that mixed with the explosive cocktail of a clear neurosis and the distance and acclimatization to socializing with adults from a very young age as is the experience of an only child, especially one in the spotlight. Throw in a cheating husband who reeks of underlying misogyny and detachment and an upheaval of her life without her permission and you get a ticking time bomb about to be set off.

The Explanatory Soliloquy

Amy’s “cool girl” speech that takes place in the film at about the halfway mark—during the twist revelation—is a quote you’ll find many women nodding along with. It’s also the part of the film that many who have claimed it is sexist or misogynistic cite. Talk about splintered perspectives. Yet, in its entirety, it exemplifies how grey Amy is and how she manages the feat of being both a misandrist and also exhibiting internalized misogyny

“Nick loved a girl I was pretending to be. “Cool girl”. Men always use that, don’t they? As their defining compliment: “She’s a cool girl”. Cool girl is hot. Cool girl is game. Cool girl is fun. Cool girl never gets angry at her man. She only smiles in a chagrined, loving manner. And then presents her mouth for fucking.” Gone Girl (2014)

Amy soliloquizes while driving down the highway, staring at other ‘cool girls’ in the cars driving passed her with disdain. David Haglund took issue with this moment, as did many others. It was Haglund’s point of contention with calling this film ‘feminist’, claiming “When Amy recites this speech, she’s driving in a car, gazing at myriad women passing by…Director David Fincher chose the images, not of men but of women, to coincide with Amy’s words. So while the words condemn men, the corresponding images implicate women, making everyone culpable. It becomes a condemnation of women themselves, that they shouldn’t fall into the trap of pantomiming this performance.”

And that’s kind of the point. Women identify with the speech; they too have fallen victim to men’s expectation of female performance in a relationship. But such identification on behalf of female viewers doesn’t mean that Amy’s point of contention is solely coming from her hatred of men. She also hates the women themselves, and herself, for ever complying because it will never be enough. Amy chastises, “But Nick got lazy. He became someone I did not agree to marry. He actually expected me to love him unconditionally. Then he dragged me, penniless, to the navel of this great country and found himself a newer, younger, bouncier cool girl,” Gone Girl (2014).

And that’s kind of the point. Women identify with the speech; they too have fallen victim to men’s expectation of female performance in a relationship. But such identification on behalf of female viewers doesn’t mean that Amy’s point of contention is solely coming from her hatred of men. She also hates the women themselves, and herself, for ever complying because it will never be enough. Amy chastises, “But Nick got lazy. He became someone I did not agree to marry. He actually expected me to love him unconditionally. Then he dragged me, penniless, to the navel of this great country and found himself a newer, younger, bouncier cool girl,” Gone Girl (2014).

Focusing on Amy’s self hatred and internalized anger derives from the adaptational baggage of zeroing in on Amy’s headspace in a visual medium. While reading, the audience can picture the men in their lives they have met who have had those expectations and failed them just as miserably as Nick did. But in film, one must use the power of the visual medium to clarify and interpret expressly and sufficiently.

Amy’s “cool girl” speech in the film and the visual elements that come along with it do highlight Amy’s headspace and hit home the notion that of all these women are just more Amys (or at least the most sympathetic part of her) to a certain extent. It opens up the universal notion that women are told to be something they are not from a very early age and continue that way for much if not most of their lives. As Amy drives passed them, she believes she has achieved the greater knowledge; the outside perspective.

But that does not erase that at some level, this is internalized misogyny as well. And that cannot be forgotten when we discuss the implications of her perspective on relationships and men in particular. After all, even feminists can internalize the misogyny so prevalent in our culture, and feminist narratives can point this out and still be feminist.

The Subversion of Expectations

Gone Girl, structurally and tonally, is split into three different films of three different genres. Within that comes the different interpretations of Amy. The second we know she’s alive, see who she truly is, and find out she is not completely victimized, people begin to hate her. From that comes the fear that she’s ‘unlikable’. Her “cool girl” speech is the bridge that marks the shift from ‘victimized battered wife that went missing Amy’ of the first act to her refusal to be the “cool girl” anymore. To maintain a high level of commitment and effort in the relationship when her partner refuses. From that point on, her psyche begins to unravel, and it’s where a great many of the critics began to squirm. People don’t want to see roles and archetypes broken if they are the ones being favored by those already in place.

Gone Girl, structurally and tonally, is split into three different films of three different genres. Within that comes the different interpretations of Amy. The second we know she’s alive, see who she truly is, and find out she is not completely victimized, people begin to hate her. From that comes the fear that she’s ‘unlikable’. Her “cool girl” speech is the bridge that marks the shift from ‘victimized battered wife that went missing Amy’ of the first act to her refusal to be the “cool girl” anymore. To maintain a high level of commitment and effort in the relationship when her partner refuses. From that point on, her psyche begins to unravel, and it’s where a great many of the critics began to squirm. People don’t want to see roles and archetypes broken if they are the ones being favored by those already in place.

Combating the claims that the film itself and she as the screenwriter are steeped in misogyny, Gillian Flynn told The Telegraph “I can’t believe it’s 2014 and we’re still discussing this. That somehow you dislike women if you are writing about really bad women. It’s denying an entire range of human capacity. Even good characters have their dark sides and I think it is important that women aren’t seen as innately good.”

So yes, Amy does terrible things. But the complexity and development that exists within the writing of her character allows us to empathize with her while also giving us permission to refuse to sympathize. While she might internalize some level of misogyny, calling her character a sexist portrayal falls into that same trap. It refuses to allow women to exist in certain roles in a story that doesn’t normally make space for them. Gone Girl recognizes that women, just as men, exist in every point across the spectrum of morality.

In the audio commentary track of the film, Fincher discusses the three different aspects of the film: murder mystery, thriller, and satire. It is within all of these genres together, and the expectations and formulas for said genres, that Fincher and Flynn allow Amy’s spiral into madness to come from a deconstructive place of reclamation. Framing Amy in all of that subverts the tropes and archetypes of the genres she exists in. It’s a constructed retrospective on narrative storytelling and media. From that comes meta critique about the film’s own genre as well as the current state of the entertainment we rapidly consume.

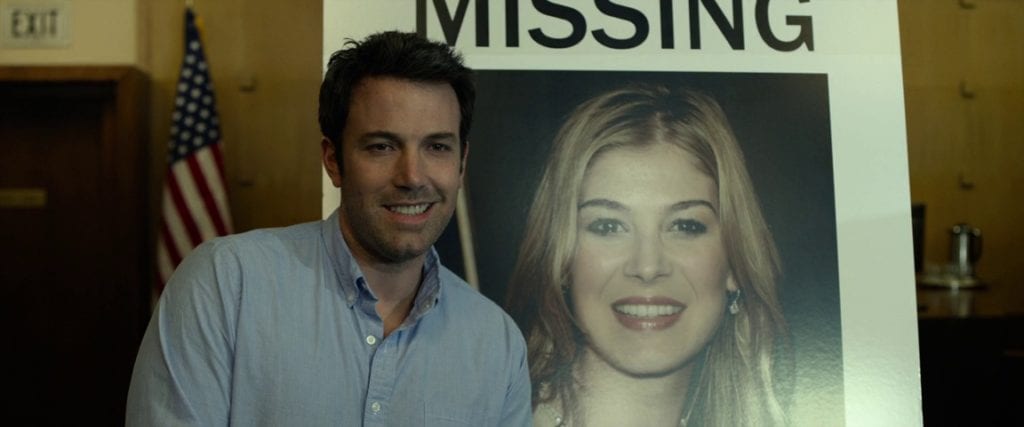

The first thread of the film, the murder mystery procedural, paints Amy as a figure we know both in our storytelling and in our media. She embodies the archetypal female of the genre: the victim and martyr both that society wants women to be and that our media frequently paints them to be. The media in the story makes Amy out to be an absolute angel. She’s once again “Amazing Amy,” never allowed to be anything more or less. It refuses to recognize her grey-ness because that would make her more complex than they want her to be.

The female victim in the genre, the (frequently dead) wife or young woman that we fall in love with through other’s memories of her, is never allowed to tell her own story. People eulogize the person everyone thought or said she was, rather than her reality. Amy represents the perfect notion of that, the blonde ivy league graduate, and the media continues this narrative by making her the “Amazing Amy” she has lived in the shadow of her entire life.

This subversion continues as we move into the thriller part of the film, a genre so often riddled with the femme fatale that Amy refuses to be. When we move into this part of the film, Amy is saying goodbye to the “Cool Girl” she pretended to be and is turning herself into what one would imagine the opposite of a femme fatale is. She is working to ensure Nick’s ruin, but is no longer relying on the seductive means of tackling that. With mousy brown hair, a few extra pounds, glasses, and clothes that look like they are from Walmart, Amy is revealed to us, in the thriller, in her femme fatale role looking like anything but a femme fatale. It is a brilliant metaphor for how women see liberation  versus how men do.

versus how men do.

Men, who often are the writers of the noir genre, have usually give femme fatales an unrealistic beauty standard they must comply with to even remotely allow them to become the powerful and merciless creatures they are. Women aren’t allowed to be horrific if they aren’t also beautiful. The genre would expect Amy to continue being the “Cool Girl” if she is to be a fatale bringing men to their heels. But she does it with pride while munching on a KitKat and with splotchy cheeks. She looks unrecognizable and astoundingly so; finally free to express with liberty everything that she has been holding back or lying about before.

Then, when society wants her to be that again, insists she be the “Cool Girl” she has thrown away through the voice of Desi Collings, Fincher begins to bring us into satire territory. Amy embraces her “Cool Girl” nature once again, but this time uses it to her advantage, drawing him in to bring him down. She reclaims the notion of “Cool Girl,” to both get out of the situation with Desi by literally slitting his throat mid copulation and to draw in Nick. She says has never been more alive than when they were playing the game of dancing around each other and testing one another, only now she lacks the facade it came with before.

One Woman to Represent Them All!

The reason why there has been so much mixed critical reception regarding this film, to my mind, is because of the widespread unconscious belief that women in film are meant to represent their entire gender. It’s not an unfounded notion. We’re so used to seeing a single female character, often thrown in as a love interest or side piece; when that happens, it does unfortunately fall on this lone ranger to ‘represent’ all women. However in Gone Girl, Flynn’s pen framing of the narrative purposely works against that conception. The claims that it is a misogynistic narrative actually play right into the sexist way we’ve been conditioned to view female characters in media.

The main criticism laid down is that Amy is a bad representation of women on screen, that she plays into the paranoia men feel about the female gender because of her false rape accusations and her ruthless violence. And yet we have characters like Norman Bates or Patrick Bateman that are labeled interesting character studies. They are formed from the male experience, but the audience recognizes that they do not represent the gender as a whole. So why do we force every female character on screen to be the embodiment of all women?

The lack of multiple and diverse roles for women reinforces this “one woman represents all” concept. We bring that bias with us even when a film is doing what we’ve been asking film to do for decades—treat women as people, the good, the bad and the ugly—without shying away from it. We’ve not really had a female character like Amy, who is allowed to be female and be scarily so. No one asks any more of Bates or Bateman than what is expected out of a ‘regular character’.

Not to mention, the accusation against Amy stems from the notion that she is the only prominent female in the film. That is simply not the case. Nick is constantly surrounded by women; they are our moral compass in all of this madness. From his vivacious and honest sister Go, to the smart and tough detective Boney, to Amy’s mom and the two television personalities, we are shown a wide field of women who are all incredibly different from one another and from Amy.

Thus, there is no need to pigeonholed her and thereby stunt her character and arc. Norman Bates wasn’t a commentary on the relationship all men have with their mothers or the pure violence against women that men have within them. Neither was Patrick Bateman. Therefore, Amy doesn’t represent her entire gender, but rather represents a vertical slice of what the outcome of the experiences of that gender in this world could look like.

Fincher and Flynn work together to ensure that Amy is both written and framed visually in the narrative as who she is. She’s a complex and incredibly complicated individual but at the same time one that is absolutely psychopathic. They give her room to be built up into the martyred victim we have seen time and time gain only to break that down. The film allows Amy to revel in her intelligence as she plots the grand scene of framing her husband for her own death and gives way for her to be so much more than the archetypes women fall prey to in the various genres.

She is every archetype and none. She is self-aware in that sense. Having had the experience of being a woman in this society, she uses said knowledge and awareness to work and play each of these constricting archetypes to her advantage, turning them and their boundaries on their head.

Amy is the ‘virgin’ goddess to the public, the evil ‘whore’ to Nick, and the ‘femme fatale’ for herself. She painted her own story, tweaking public perception to subvert expectation or play into it, no longer letting her husband or her parents dictate her story. This is hers and hers alone as she dreams for the public to worship her, Nick to respect her, and work out just who she is and what she needs for herself.

Despite the fact that many have criticized the film, calling it ‘misogynistic’ because Amy encapsulates a caricature of what men most fear, she does so because she knows the implications of doing so. Amy didn’t create the implications, the implications created her. She is a product of what society has told women they can or cannot be and has flipped all of that on its head. However questionable those decisions are, they’re hers. And she subverts all of the tropes and archetypes the media (and audience) expect her to fulfill, finally writing her own story rather than living out someone else’s.