Part of the GRRM Reading Project.

Decades before becoming the world-famous writer we all love but hate to wait for, George R. R. Martin (GRRM) was making a name for himself writing science fiction. And Seven Times Never Kill Man marks another step in this path, expanding Martin’s sci-fi universe known as “Thousand Worlds.”

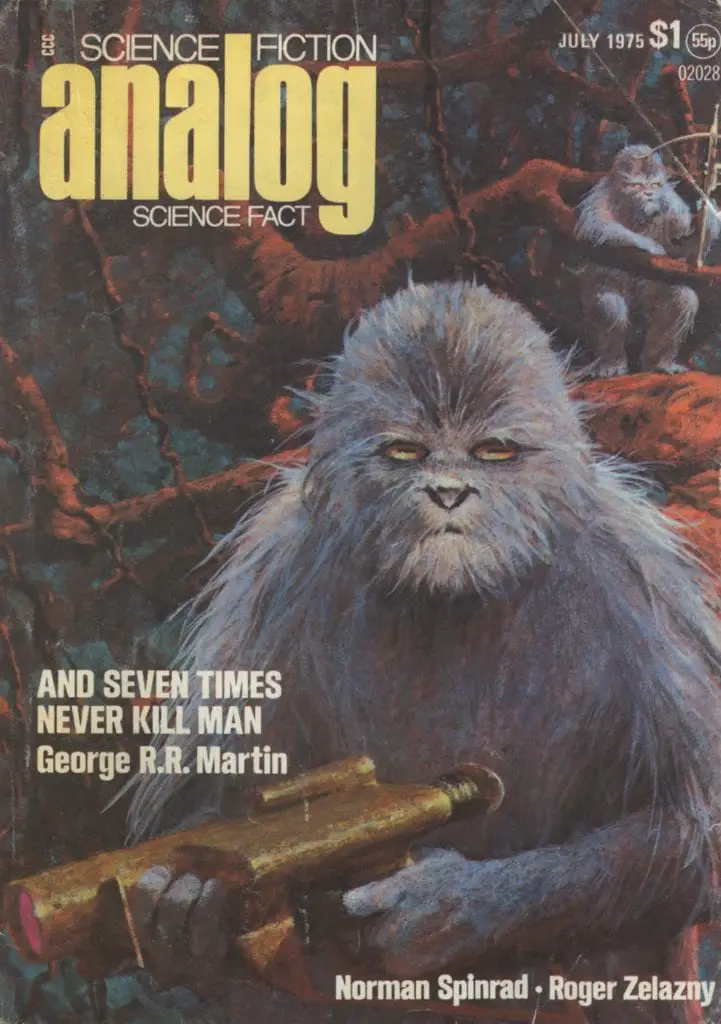

Written in 1974 and published on Analog in the following year, the story was nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Novelette. It became one of Martin’s many Hugo losers, but just the amount of nominations he got is already impressive.

And Seven Times Never Kill Man also generated this iconic Analog cover by John Schoenherr:

So let’s have a look at another corner of Martin’s “future history” universe.

In a thousand thousand woods and a single city

And Seven Times Never Kill Man takes us to the world of Corlos (no, not the same one), home of the Jaenshi. A sentient humanoid species, the Jaenshi structure their society around their religious beliefs, with each of their small clans worshiping a different pyramid as if it contained their gods.

This society is slowly being annihilated by the Steel Angels, a belligerent human cult devoted to the pale child Bakkalon. The self-titled children of Bakkalon believe it’s their duty to expand and conquer, and Corlos is next on their plans. As the story starts, the pacifist and wild Jaenshi are paying a heavy price for having killed one of the Steel Angels, and now their children hang on the walls of the Angel city.

The cruelty of the Angels enrages Arik neKrol, a human trader who loves Jaenshi art. NeKrol convinces his fellow trader Jannis Ryther that they need to help the Jaenshi, and Jannis leaves the planet promising to return in one year with weapons. Now it’s up to neKrol to teach the Jaenshi how to use them.

Turns out most Jaenshi are uninterested in neKrol’s weapons, confident that their gods will protect them. The exception is a small group of exiles—Jaenshi whose pyramids and clans were destroyed, but they couldn’t find home among others. Led by a Jaenshi known as the bitter speaker, the exiles are determined to fight the Angels and protect the surviving clans.

When the children of Bakkalon advance against a huge Jaenshi clan, neKrol and his ragtag bunch of exiles move to protect them. Strange events take place when the Angels try to destroy this clan’s pyramid:

“NeKrol stood paralyzed. The pyramid on the rock was no longer a reddish slab. Now it sparkled in the sunlight, a canopy of transparent crystal. And below that canopy, perfect in every detail, the pale child Bakkalon stood smiling, with his Demon-Reaver in his hand.”

Most Steel Angels believe it to be a miracle, except for weaponsmaster C’ara DaHan. Before he can order the destruction of the pyramid, he’s killed by one of the exiles. This prompts an armed conflict between Jaenshi and children of Bakkalon, with several deaths on both sides, including neKrol.

Little is known of the Jaenshi after this conflict, but the bitter speaker and two other exiles meet Jannis and prepare to leave with her. The Steel Angels still live in their city, but they become obsessed with their new found god/pyramid. They burn their winter provisions and kill their own children, who now hang on the walls of the Angel city.

They will never kill a man again

As Martin develops his writing and evolves his style, his stories become longer and more complex. And Seven Times Never Kill Man has a wide range of elements worth analyzing, and a few that specifically stood out to me.

Those that know Martin from A Song of Ice and Fire (ASOIAF) are aware of how much he likes to play with the expectations of his readers. Yet his plot twists are born organically from the narrative, seeded and foreshadowed long before they happen. They still surprise you, but at the same time make you wonder how you didn’t see them coming.

This reading project shows that Martin has been playing with reader expectations since the ’70s, with variable degrees of success. Stories like The Second Kind of Loneliness or This Tower of Ashes have important plot twists that change our perception of the story. At the same time, they’re also quite abrupt, and I can’t imagine that many readers guessed those twists beforehand.

And Seven Times Never Kill Man feels closer to ASOIAF, in which the surprise comes from our own narrative expectations. Storytelling conventions tell us that the novelette won’t end simply with the Angels annihilating the Jaenshi and calling it a day. We expect the Jaenshi to fight back, and the narrative toys with this possibility. Then the conflict goes a different route, but one that completely makes sense with everything we’ve been told about the Jaenshi and the Angels. The Jaenshi do defeat the Angels, after all. Just not the way we would have expected them to.

To be honest, I don’t quite like unexplained supernatural elements being so crucial in the end, even knowing that this is Martin’s favorite approach to magic. But the surprise ending is rooted in what we know about that world and those cultures. It’s not a twist because it came out of the left field, it’s a twist because we were expecting a promise that the story never made.

The old gods and the new

Martin goes deeper in the worldbuilding for And Seven Times Never Kill Man than for his previous works. The novelette is clearly part of a larger universe, with several references to other Thousand Worlds planets and cultures.

Truth be told, some of those references feel expository or like clumsy name-dropping that adds very little to the story. But the meat of the narrative, the Jaenshi and Steel Angel cultures, is still remarkably well-developed. We get a good sense of who they are, what they believe in, or how their society operates. Without this foundation, the ending simply wouldn’t work.

The two cultures are clearly distinct and operate according to very different values, but at the same they share important similarities. Jaenshi and Angels have their faith as the center of social organization, with those beliefs also determining who’s excluded or included in that society. There’s a strong focus on collectivity before individuality, with an emphasis on hierarchy and the role of the religious leaders. Both leaders seem confident in their beliefs despite contrary evidence. The Jaenshi and the children of Bakkalon parallel each other along the narrative, so the transformation of the children of Bakkalon into a perverted version of the Jaenshi clans fits them well.

It’s no small feat to create and present two cultures so similar and yet so obviously distinct. Perhaps for this reason, both Jaenshi and Steel Angels are still largely treated as cultural blocks. It’s a struggle Martin will continue to have until his ASOIAF days, as seen in Dothraki and other Essosi cultures. We don’t get a sense of the internal diversity of these cultures because we don’t see the individuals that are part of them. The ones we do get to know, like the bitter speaker or C’ara DaHan, are treated as exceptions.

The text of And Seven Times Never Kill Man feels almost anti-religious sometimes, though I don’t believe this was Martin’s goal. It’s just that his gods are so alien to us. Their true nature is unknown, their intentions a mystery. We see this with the gods of ASOIAF as well: from R’hllor to the Drowned God, Martin’s pantheon is terrifying. No wonder in both stories we only have the words of the prophets, who are often wrong or missing important pieces, but never the gods themselves. We cannot reach Martin’s gods. But which gods can we reach, after all?

The Heart of Bakkalon was sunk forever

Unlike Martin’s usual close point-of-view structure, And Seven Times Never Kill Man presents us with several points-of-view. We follow Arik neKrol more often, but also Jannis Ryther or Wyatt and his Steel Angels. Out of all the main players in the story, we only miss a Jaenshi perspective.

Having the point-of-view of the Steel Angels gives us a better insight in their society and their motivations, as well as the blind spots that will ultimately cause their downfall. The absence of a Jaenshi point-of-view, in turn, makes their culture more mysterious to us. The only Jaenshi that we get to know better, the bitter speaker, is clearly no longer operating by the same rules. This makes the Jaenshi culture truly alien to the reader, allowing multiple interpretations of the final conflict between them and the Angels.

What truly happened with the pyramid of the waterfall clan? Actually, what are the mysterious pyramids the Jaenshi worship? Who built them? How and why did the Jaenshi create sculptures of alien gods? Why did they create the statues of Bakkalon? Did the talkers know what was going to happen? What’s the meaning of the golden glow in Jaenshi’s eyes, absent in the bitter speaker but present in the Steel Angels by the end? Does the Angels killing their own children have some connection with the population control of the Jaenshi? What’s the nature of the Jaenshi gods? Why do the bitter speaker and the other exiles change so much as they distance themselves from these gods? I could go on forever; this story opens more questions than a season of Lost.

I haven’t found any satisfactory answer for those questions, be it by myself or among fan circles. However, I don’t think Martin would have introduced the idea of the “vampires of the mind” or “soul-sucks” for no reason. Being this sloppy with loose ends doesn’t suit Martin’s style, even in his early days. Could this be the key to explain the fate of the Angels? Or is this reference too small and not followed through enough to earn such importance in the narrative? I go back and forth with this idea.

What about you? What’s your interpretation for the ending? What aspects of the story stood out for you? Let me know in the comments!

Next time: Martin goes horror in “Meathouse Man”!