Part of the GRRM Reading Project.

In the summer of 1971, George R. R. Martin (GRRM) wrote a story every two weeks, on the average. Despite going through a difficult time of his life, he created seven stories in total. All of them would sell at some point or another, though some would take “four or five years and a score of rejections.” Two of those stories became important milestones for him: The Second Kind of Loneliness and With Morning Comes Mistfall. Martin believed those two would make or break his career as a writer, since:

“These were strong stories, I was convinced, the best work that I was capable of. If the editors did not want them, maybe I did not understand what makes a good story after all . . . or maybe my best work was just not good enough.” (George R. R. Martin – Dreamsongs vol. I)

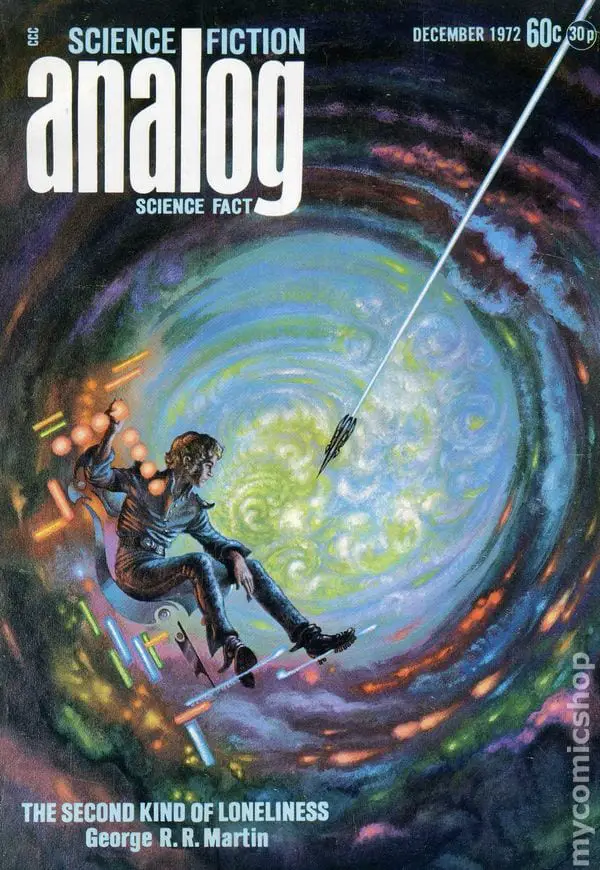

The Second Kind of Loneliness was written last, but published first. It was the cover story of the December, 1972 issue of Analog, with a beautiful cover by Frank Kelly Freas that GRRM deeply regrets not buying when he had the chance.

According to its author, The Second Kind of Loneliness was,

“an open wound of a story, painful to write, painful to read. It represented a real breakthrough for my writing. My earlier stories had come wholly from the head, but this one came from the heart and the balls as well. It was the first story I ever wrote that truly left me feeling vulnerable, the first story that ever made me ask myself, ‘Do I really want to let people read this?’” (George R. R. Martin – Dreamsongs vol. I)

We’re lucky he did, so let’s have a look at it.

Two Kinds of Loneliness

Spoilers for “The Second Kind of Loneliness” ahead

Six million miles beyond Pluto lies a tiny hole in space. It can be enlarged and ripped open with insane amounts of energy, becoming a structure akin to a wormhole: the nullspace vortex. Around it was built the Cerberus Star Ring, a silver ring with over a hundred miles of diameter that provides the necessary energy to wake this vortex. Traversing the nullspace, ringships can reach distant planets and Earth colonies.

The Second Kind of Loneliness is written as the journal of a nameless narrator, the sole man to crew the Cerberus Star Ring. His job is to “guard a hole in space” and control the opening of the nullspace vortex for ringships. We follow his records from the moment he learns his replacement is on the way. After four years of star ring, the narrator only has three months left before the Charon arrives to take him back home. His narration explores his feelings during those final months and the reasons that brought him to space.

Turns out our narrator was very lonely on Earth, and with a loneliness deeper than being the sole crewman of a distant star ring. He wanted to be loved, to feel needed, so he projected those feelings on a woman named Karen. Karen just wanted to be friends, though, and the narrator couldn’t deal with that rejection. So, as one does, he isolated himself in space.

As days go by, the narrator becomes increasingly conflicted on whether he feels ready to go back to Earth or not. He starts having nightmares about Karen and other moments of isolation and vulnerability, and those dreams only fade when he gazes the stars and the nullspace vortex through hologram projections. As ringships are irregular, each time that he admires the vortex can be the last.

The day when the Charon was supposed to arrive comes and goes, with the ship being late for unknown reasons. The narrator spends more and more time out in the open. He even wakes the vortex without any ringships nearby, something he knows to be forbidden. This prompts him to put the ring in proper shape for his relief, and that’s when he learns the terrible truth.

The Charon wasn’t late, it arrived months ago. Overcome by mixed feelings and not knowing what his replacement would think of him, the narrator decided to wake the nullspace vortex just as the Charon moved to dock. The ship didn’t survive the impact, but there was no debris, which made everything easy to forget. The narrator has been living in the wrong time for months.

On the last entry of the journal, the date goes back a couple of months. The narrator finds his calendar broken for some reason, but at least he has just learned his replacement is on the way.

The Many Layers of GRRM

I reread this story a few times and I’m still not sure what to make of it. Sometimes its flaws bother me, sometimes they don’t. There are times I find the main character relatable, others I find him pitiable, others despicable, and then all three together. I come up with a new interpretation every time I read it and different readers may have a distinct take still.

That’s good, I believe. The Second Kind of Loneliness has a lot we can sink our teeth into, with more layers and more depth than any of Martin’s previous writing. I can understand why he felt vulnerable creating it: it’s a very intimate story. The journal format reinforces this impression, but the extensive examination of the narrator’s feelings and fears goes much further than any of the stories he has written before it. It’s a character-driven narrative, something Martin would come to excel at.

The story also has themes and tropes that will come back in GRRM’s subsequent works, something I’m particularly interested in.

Unreliable narrators

Fans of A Song of Ice and Fire (ASOIAF) will be familiar with Martin’s fondness for unreliable narrators. All point-of-view characters in that series are assumed to be biased or unable to remember all facts correctly, which is fitting when you follow somebody’s perspective closely. We’re not objective in our perception of people or events, so it makes sense that the characters we read won’t be either.

I like how Martin deals with the unreliable narrator in The Second Kind of Loneliness. We start doubting this character very soon, both in his affirmations that he’s over Karen and not afraid of life on Earth. Even before he confirms that this isn’t the case, we have the impression he’s not being entirely honest with himself.

From one journal entry to the next, the narrator’s feelings change. Not in a way that feels incongruous, but in a way that makes us question him as a source of information. The final twist, of course, consolidates the character as an unreliable narrator.

I personally found this twist poorly seeded, at least compared to Martin’s skills with foreshadowing major events in ASOIAF. It’s also not clear how the narrator found out the truth, so the whole execution of this plot twist was a bit clumsy to me. One thing I do like, though, is that we are left wondering how long this has been going on. Was it the first time he set the calendar back and forgot everything? Or maybe not? The last possibility is terrifying.

This is where unreliable narrators work best for me. They remind us that we’re reading a person’s account and those are never objective or impartial. Why do we tend to believe everything our narrators say, anyway? And how many stories can be truly objective?

Depictions vs. Endorsements

Here at The Fandomentals, we talk a lot about how much depiction doesn’t necessarily mean endorsement. Authors that deal with delicate topics or problematic characters have a lot of work ahead of them to make sure this is the case.

The Second Kind of Loneliness was quite a challenge in that regard: how do you avoid endorsing a character’s problematic behavior and beliefs when this character is your only source of information? It takes a lot of skill for that, but Martin has it.

The narrative avoids endorsing the main character’s actions because it shows that his mindset is ultimately damaging for himself and those around him. Martin walks a fine line here, because he also avoids demonizing this character. The same happens with Karen, who could have easily been portrayed negatively for friendzoning the narrator. On the contrary, we’re shown the narrator was wrong for projecting his fantasies onto her.

While she’s far from a fully-fleshed character, we get the impression Karen is her own person beyond the narrator’s memories and fantasies. It’s quite telling that she has a name when the narrator himself remains nameless, almost as if she has a personhood that the narrator lacks. As we learn from Martin’s later work, names are important.

Illusion & Choice

“It’s all done with holographs, of course. I know that. But that doesn’t make a bit of difference when I’m sitting in that chair.”

Beyond its use of unreliable narrator, The Second Kind of Loneliness constantly presents a conflict between illusion and reality. The narrator repeatedly chooses the former, and that’s a central component of his doom.

The narrator can’t deal with the real Karen not matching his expectations. While he acknowledges said expectations, he also wants to find “another Karen.” But that’s not the point! The point isn’t to find someone that finally matches your fantasies, but to question those same fantasies. The point is to have expectations that real people can meet and to be capable of accepting those people for what they are.

The narrator chooses to contemplate the stars and the nullspace vortex, even knowing that what he sees are just holograms. He chooses to brood in space over facing real life on Earth or any of the colonies. He forgets his actions instead of facing the reality of what he did.

“Too busy star watching at the time to do what I should have been doing.”

One of my favorite aspects of the story is how much the narrator has agency and his tragic fate is a result of his own choices. That’s another recurring element in Martin’s stories: what happens to his characters is connected to their own actions or lack thereof. Doing the right thing isn’t easy and won’t always reward you, but you have a choice.

I understand that the narrator of The Second Kind of Loneliness is in a fragile position. Four years alone in space won’t do your mental health any favors, especially when it’s implied his communication with other humans is very limited. Still, that doesn’t excuse his actions and choices, particularly regarding the fate of the Charon.

Aside from constantly choosing illusion over reality, the narrator chooses his fear of life. Both Earth and the colonies are full of possibilities to explore, but he has to choose them, and in doing so accept the risks they bring. In the end, his fear is so great he goes to great lengths to avoid facing life. But not acting is also a choice.

“Older memories too. Infinitely less meaningful, but still painful. All the stupid things I’ve said, all the girls I never met, all the things I never did.”

Aside from the rejection by Karen, the narrator’s painful thoughts seem to be connected to things he didn’t do more than those he did. Abstaining from life is also one of the biggest sources of his loneliness, especially the second kind.

There’s an interesting (if a little too on the nose) symbolism with the names Martin borrows from Greek mythology. Charon is the ferryman that carries the souls of the newly deceased to the underworld, guarded by Cerberus. In The Second Kind of Loneliness, the narrator seizes the Cerberus Star Ring for himself, destroying the Charon to prevent the living from entering and the dead from leaving. He excludes himself from the possibilities of life, be it Earth or its colonies.

And why? Well, because the world of the living includes rejection, vulnerability, disappointment, failure… and loneliness. Of the two kinds.

On The Second Kind of Loneliness

“I know about loneliness. It’s been the theme of my life. I’ve been alone for as long as I can remember. But there are two kinds of loneliness.”

The main theme of this story is, of course, loneliness. Early on the narrator presents us the idea that there are two kinds of loneliness. The first is what common sense tells us, the physical isolation from other people. It’s the isolation of a lighthouse or the man among the stars. It can be maddening, but also pleasant, beautiful, solemn:

“It’s beautiful out here. Lonely, yes. But such a loneliness! You’re alone with the universe, the stars spread out at your feet and scattered around your head.”

But that’s not all:

“And then there is the second kind of loneliness. You don’t need the Cerberus Star Ring for that kind. You can find it anywhere on Earth. I know. I did. I found it everywhere I went, in everything I did. It’s the loneliness of people trapped within themselves. The loneliness of people who have said the wrong thing so often that they don’t have the courage to say anything anymore. The loneliness, not of distance, but of fear. The loneliness of people who sit alone in furnished rooms in crowded cities, because they’ve got nowhere to go and no one to talk to. The loneliness of guys who go to bars to meet someone, only to discover they don’t know how to strike up a conversation, and wouldn’t have the courage to do so if they did. There’s no grandeur to that kind of loneliness. No purpose and no poetry. It’s loneliness without meaning.”

The way I see it, the second kind of loneliness is isolation on an emotional level. It’s being surrounded by people and still feeling alone. It’s feeling nobody understands you, or hears you, or sees you, at least not the real you. Our narrator knows very well which kind of loneliness he dreads the most:

“Oh yes, it hurts at times to be alone among the stars. But it hurts a lot more to be alone at a party. A lot more.”

I’d argue that both kinds of loneliness took a toll on the narrator, but it was the second kind that drove most of his decisions. In the Cerberus Star Ring, he dealt with the first loneliness constantly, but on Earth or its colonies, the second kind would be evident. His feelings of inadequacy, of vulnerability, his fear of being alone, his inability to reach people and to be reached… all that would be exposed.

That’s where I find the narrator most relatable. After all, how do we deal with this? We can easily solve physical isolation, but how do fix the second kind of loneliness?

Loneliness is a recurring theme in George R. R. Martin’s works. Even A Song of Ice and Fire has it constantly, with its POV characters scattered, ladies locked in towers, kings and queens with no friends, lone wolves searching for their pack, houses and kingdoms isolated despite the need to unite.

However, it’s A Song for Lya that I remembered the most with this story. A Song for Lya, written a couple of years after The Second Kind of Loneliness, also examines loneliness extensively. Take Robb’s dream in the end of the novella, for example:

“I was alone, forever alone, and I knew it. That was the nature of things. I was the only reality in the universe, and I was cold and hungry and frightened, and the shapes were moving toward me, inhuman and inexorable. And there was no one to call to, no one to turn to, no one to hear my cries. There never had been anyone. There never would be anyone.”

In both stories, loneliness has some sort of external embodiment. For The Second Kind of Loneliness, it’s the Cerberus Star Ring with its nullspace vortex. For A Song for Lya, it’s “the infinite darkling plain with its starless sky and black shapes in the distance”.

The loneliness that we see in A Song for Lya is also the second kind. That’s the loneliness that all people experience, even those capable of being as together as two humans can. That’s the loneliness they can finally put an end to, and be “forever and forever, and belonging and sharing and being together.”

The two stories complement each other. Where The Second Kind of Loneliness presents us a problem and asks us a question, A Song for Lya offers us a solution—at great personal cost—and the closest thing to an answer that we’ll get:

“Maybe I still hope, for something still greater and more loving than the Union, for the God they told me of so long ago. Maybe I’m taking a risk, because part of me still believes. But if I’m wrong . . . then the darkness, and the plain . . . But maybe it’s something else […] Perhaps there is a human answer, to reach and join and not be alone, and yet to still be men.”

It’s a non-answer, it’s a renewal of the quest. Both stories seem to say that you can’t really end the second kind of loneliness, not forever. At some point there will be disappointment, rejection, loss, grief, pain. It’s part of human experience and nobody can feel that for you. Nobody can know everything about you or do exactly what you expect or complete you. There will always be some kind of gap between you and others. Life on Earth can be scary and dull and ugly at times. There’s no cheating that.

Yet both stories also say that we must attempt to find each other. We must make an effort to connect with those distant stars. Whatever connections we manage will be even more precious because we know the effort behind them and how much they can mean. We must attempt to face life in all its tragedy and its glory. Nothing good comes if we don’t.

Closing thoughts

Despite its flaws, The Second Kind of Loneliness is an intimate and disturbing story that gives its readers a lot to think about. It’s a good read in isolation, but it works even better when you consider the body of GRRM’s work and his subsequent explorations of its themes. No pun intended, I guess?

Next time: we’ll read the other child of the summer of 1971, the beautiful and evocative “With Morning Comes Mistfall”.