Let me begin from afar. These days overt Orientalism has become uncivilized. People now mostly understand the added weight of racism and colonialism it bears. (Or at least they pretend to understand.) But Western culture still needs the Other to imagine itself in comparison to. So they take a vague Eastern Europe, populate it with by in name Slavic monsters and play Orientalism to their content.

Nobody, they think, is offended. Eastern Europe is, for better or worse, majority white land. It was not colonized, either (well, it mostly was, just not by Western Europe). The idea that distorting cultures of several independent nations into one blurred and distinctly supremacist trope is bad with or without added burdens doesn’t (it seems) cross their minds. For example, that’s why in a quite good series of books the Ottomans are presented in a balanced light while the commonplace Orientalist narrative is instead shifted to (presumably white) Orthodox Romanians.

I do not presume that balanced approach to foreign cultures is somehow bad, mind you. On the contrary, I insist that there should be no supremacy narrative, no cultural appropriation, no Orientalist fantasies at all. Because each and every of them has this toxic touch of Ubermenschen observing exotic yet not fully human barbarians.

Then and Now

Of course, it didn’t start yesterday. Shakespeare created his seaside Bohemia in XVI century, after all.

Blurring the line between the human West and inhuman East in depicting Eastern Europe was commonplace. The difference in religion made the gap even more pronounced. Germans chided the Czechs for being natural barbarians; English travelers mused that Muscovites were naturally dark-skinned but apparently bleached by cold. Before the great colonization Eastern Europe had provided those in need with an Other.

With time it evolved into two distinct imaginary places: a Ruritania, more down to earth and realistic, and its dark and full of terrors twin, the Uberwald. For some reason, they have two perfect twins in the Orientalist narratives, first focusing on simplified/imaginary daily life of an “exotic” country, while second ensnaring with imaginary terrors of foreign land.

Today the constant conflicts in South-Eastern Europe (Balcans, Moldova, etc) and frequent incursions of UN and NATO corps there give the missing colonialist/conquerer vibe to the narrative. Like in classic Orientalism, the hero comes with a sword to encounter the cunning, honor-less yet in the end power-less adversary (as seen in MCU).

But this was a broad picture. Let me get to the monstrous specifics.

Horrible Horrors

Horror genre has always been…let’s say not too progressive. It thrived on the fear of the Other, on exploiting gender violence and femicide, racial violence and racial myths. No surprise, horror authors couldn’t help themselves from allure of Eastern European exoticism.

But if the XIX century used compartamentalised Austro-Hungarian something under the guise of Romanian, now the trendy moniker is “Slavic”. Almost anything from this corner of Earth is “Slavic”, be it Romanian, Hungarian or Estonian (neither of those has anything to do with Slavs).

Romanian traditional embroidery is “Slavic”, vampires are “Slavic” (they are vaguely akin to Romanian folk monsters, but mostly are Western European fantasy), Maksimoffs’ Roma mother is “Slavic”, everything is “Slavic”.

They have a cadre of common “Slavic” monsters: Baba-Yaga, Vampire, Rasputin. To compensate for lack of knowledge they even invent their own monsters, with vaguely “Slavic” names. Mummy cartoon gave us “gogol” (which is either a duck or a Russo-Ukrainian author), while J.K. Rowling invented “a pogrebin”.

All this constitutes something known as “cranberry storytelling” in Russia–name apparently hailing from some French adventurer of old, describing his encounter with peasants sitting under a giant tree-like cranberry and waiting for the berries to fall because they are too lazy to climb and gather them. (Cranberry being a really big thing in Russian traditional cuisine.) Cranberry storytelling means you take something from a culture, engorge it, decorate it with as many tropes as you can, remake it according to your cultural stereotypes and sell as ethnographic truth.

Combating the Cranberry

So, what’s wrong with the traditional cadre?

Well, nobody out here sees Rasputin as anything but a historic figure (well, apart from small group of those who see him as a religious figure and even a saint). Baba-Yaga is hardly something “Slavic” either: she is of Iranian origin and more importantly is hardly present in most of the Slavic cultures. Both are Russian specialties, that’s true; but “Slavic” has to be something more.

There are many Slavic nations and there is little in common between them. Their cultures sundered too long ago and went through too different processes to be close. Yet there is a small amount of folk monsters that are truly and distinctly Slavic.

Here they are, for your use or for your interest.

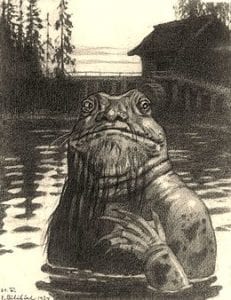

The Master of Waters

Fish-like or frog-like Master of Waters is a common figure throughout Slavic folk lore. He has no distinct origin story; mostly he just is, and from a scholar’s perspective what he is, is ancient god. And his godlike qualities linger the longers of all Slavic “Masters”.

He has a sacred mount: Master of Waters is usually imagined riding a giant catfish. In some regions there was even a taboo on fishing “devil’s mount”. He has a long and sad tradition of human sacrifice. Even in XX century there were places where people hesitated to save a person from drowning, considering this a will of Master of Waters.

Less terrible sacrifice was commonplace. Especially those owning a water mill would throw some amount of money to the pool—it was thought Master of Waters loved those pools and had his council with millers.

Among his peers he is the most powerful, the most respected and the most godlike one.

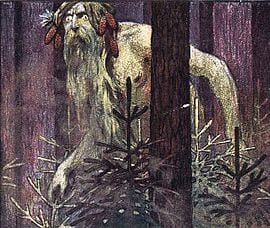

Master of Woods

This one is less pronounced in some cultures, as lush forests are less common thing among Slavic nations. Yet the spirit of trees is there. He has less gravitas than his water friend, though.

Mostly this one is a trickster, a changeling playing his pranks on the unknowing people who wandered in his realm. If you lose your way in the forest, it’s his job. He can also turn everything you hunted or gathered in the forest into pine cones or filth, make you tire too quickly or feel sudden panic. Sometimes he turns into a bear or a boar to hunt those behaving badly, or to woo a beautiful maiden.

If you are a good person, respect him and never take all berries or mushrooms, or kill a doe or a suckling, the Master of Woods can reward you greatly. But if you try to fool him, you reward will turn into pine cones.

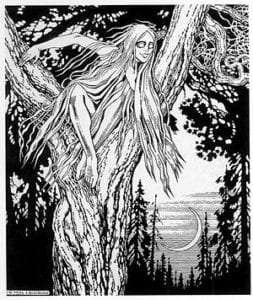

Dead Maidens

Those have many names. Like, “every nation has one or two of their own” many names. Among them is “veela” (or “vila”, or “wiła”) of Harry Potter fame, “samovila”, “samodiva”, “rusalka”, “mavka”, “kikimora”. Still it is the same creature: an unmarried woman who either died unchristened or committed suicide, transformed into a beautiful, dangerous and sometimes benevolent fairy.

Those fairies like to be in the air. They sit in the branches of the trees, or fly, or both. They are also linked to water–traditional gendered method of suicide being self-drowning. They are immensely beautiful yet have something inhuman in them. Some drip water, some have green skin, or horns, or hoofs, or wings, or lack their back.

Northern variant is relative to Scandinavian huldras; Southern took much from Islamic peris, and Central borrowed from Western fairies, yet they still share their common distinctive roots. They don’t like men much, even though they can be made into wives. They have mighty charms and pity maidens and small children. They can punish women for bad weaving or laziness, though. But usually they punish lustful men.

Chort

Chort means “Devil”, but nothing is further from that frightening religious figure than chort. Devil is powerful; Chort is almost powerless and even a self-told witch can make away with him. Devil is vicious; Chort is a mere conman, always conned by his potential victims.

Devil is something to fear; Chort is something to make fun of.

His closest Western relative is “Imp”, but Chort tries to be more respectful figure than that. He fails. He always fails, really. Of course, he has his small victories over bad people (like over Metternich on the picture above) but any decent Christian has no problem outwitting poor bad guy.

To think of it, Chort is a stormtrooper of Slavic folk lore.

And… That’s About It!

We really don’t have much in common. Actually, each Slavic nation has more common folk lore with neighboring non-Slavic nation than with some distant Slavic cousin. We are all really different. And that is great, because diversity is what makes the world so interesting, isn’t it?