Whether you see Pinocchio on the big screen or on your laptop doesn’t matter. It only matters that you see it because you must. If for no other reason than it’s one of the year’s best films.

Guillermo Del Toro and Mark Gustafason’s Pinocchio wrestles with many weighty themes but never truncates or becomes too treacly. Instead, the script, co-written by del Toro and Patrick McHale, reframes the Pinocchio story. In their hands, it becomes a tale of loss, nostalgia, and how the two can sometimes combine to aid conformity rather than comfort.

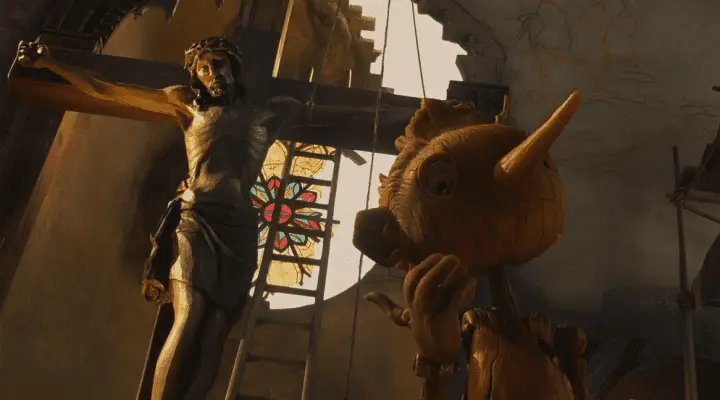

One of the changes comes from how Pinocchio (Gregory Mann) is granted life. Unlike the story we know, it is not a wish made by Gepetto (David Bradley). Instead, it is an action taken by a wood sprite (Cate Blanchett) upon witnessing the grief Gepetto expressed over his dead son Carlo, also voiced by Mann. Carlo was killed in a church during World War I while helping Gepetto work on a wooden sculpture of a crucifix.

Years later, Gepetto, in a fit of drunken grief, cuts down a tree Carlo planted and proceeds to carve a puppet boy, Pinocchio. The wood sprite, which looks more like something from the Old Testament than a fantasy creature, gives the puppet life. Though Sebastian J. Cricket (Ewan McGregor) is a little put off by all this, his home was the tree Gepetto cut down.

Gepetto awakes and is rightly horrified by the singing, dancing, and obnoxiously cheerful little boy. The last bit is one of a thousand things I admire about Pinocchio. Gustafson and del Toro don’t sandpaper the edges of Pinocchio, allowing him to be annoying and bratty. Instead, it lends authenticity to the fairy tale.

The stop-motion animation allows Gustafson and del Toro to bring a tactile delight to Pinocchio. Gepetto’s creation of Pinocchio resembles the mad doctor Frankenstein’s late-night activities. He is a wooden boy crudely carved from the husk of a tree, with his head with gnarled branches for hair and gangly limbs.

The artwork and craftsmanship are a kind of grotesque beauty. You can see wrinkles on Gepetto’s knuckles and the sallow skin of the monkey Spazzatura (Cate Blanchett). Del Toro has always been a director who understands dark beauty and how to find beauty in what others would find grotesque.

His kinship with the outsider, unloved and monstrous, makes Pinocchio a perfect fit. Together with Gustafson and McHale, they craft a moving tale of fathers and sons and how a desire for things to return as they were can lead to the decay of the present. Del Toro and Gustafson express this in Gepetto’s annoyance at Pinocchio not being Carlo or how the Podesta (Ron Pearlman) can not see that his love for his country’s past has warped the love and the future for his son Candlewick (Finn Wolfhard).

Gone is the moralizing of past Pinocchios. The filmmakers have brushed aside easy platitudes and replaced them with exquisite creations and lovingly crafted art designs in service of laying the artist’s soul bare onscreen. Pinocchio is fueled by imagination and heart; every frame is filled with textured rendering of creativity and the effort of craftsmanship.

McHale and del Toro pluck at so many ideas and play with so many themes that Pinocchio often feels overwhelmed. I was fascinated by the duality of how the film played with the deeply held Catholic beliefs and how Gustafson and del Toro gleefully reveal a world of magic that is both separate but visually profoundly inspired. For example, Pinocchio discovers that he cannot die. He is warned by Death (Tilda Swinton), a sphinx who lives in a chamber of hourglasses, that he will never learn of the sweet gift and curse of mortality. With so many films afraid to even broach death, there is a certain spiritual freedom that del Toro and his co-conspirators bring to Pinocchio by embracing its inevitability.

If all that wasn’t enough, there is Pinocchio’s ill-advised partnership with the wicked Count Volpe (Christoph Waltz). Volpe is an ex-aristocrat, a Mussolini (Tom Kenney) fan, and sees a chance to return to his days of being among the rich and powerful in Pinocchio. As a result, Volpe represents capitalism, fascism, and the simple human frailty of greed and fear.

I have only just now realized I’ve left out one of the more magical and melancholic soulful aspects of Pinocchio. It is a musical. Alexander Desplat composed the songs and the rest of the film’s spritely haunting score, with the lyrics penned by Roeban Katz and del Toro himself. The songs, as they do in all great musicals, erupt from the deep wells of emotions of the characters.

“Ciao Poppa” comes off at first blush as simple, but it resonates in my memories, pulsating with emotional complexity. Likewise, Pinocchio’s “Everything is New to Me” stands out as it feels like something from Sondheim or Bacharach. Joyous and breathless, there is an underpinning of horror and confusion. It is both hilarious and unnerving.

But that’s Pinocchio in a nutshell. Whatever one may think of Pinocchio, it is impossible to leave the film not in awe of the craft, whimsy, and heart on display.

Few films this year make me want to wrap my arms around them, like Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio. A stunningly and lovingly hand-crafted love letter to an art form and to existence itself. Oh, and the film is also an indictment of fascism, so it has that going for it too.

Images courtesy of Netflix

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!