Introduction:

Minimalist writing must be precise and to the point, the writer zeroed in like a microscope and incisive as a scalpel. Details that elevate make-believe to believable. For this week’s Short Fiction review, I will be reviewing two stories that, in their own ways, explore cultural assimilation versus liberation from dominant social forces and do so through rich specificity. With lightheartedness, Stella Wynne Herron’s 1906 short story ‘The Still of Ballywan’ addresses English-occupied Ireland and excises; Robert Olen Butler’s 1991 ‘Snow’ is a pensive Christmastime romance between two immigrants. Though originating in political queer discourse and activism in regards to a heterosexist society, the concept of “assimilation versus liberation” can be applied to discussions on colonialism, cultural immersion and capitulation, and immigration. Herron’s characters face the consequence of breaking colonial law while Butler’s characters struggle with their identities and the expectations around them in another country. (There will be spoilers for both stories.)

The Still of Ballywan:

Born to Irish immigrants, Stella Wynne Herron spent most of her life advocating for the disadvantaged. Herron is best known because of pioneering director Lois Weber’s 1916 film Shoes, which was based off Herron’s story of the same name. In recent years, scholars have unearthed Weber’s role in early film history, while ignoring Herron altogether. No scholarship exists on Herron’s work, period, which is why I’ll probably have to write her annotated biography one day.

She campaigned as a suffragette during the 1910s, and her advocation for civil rights so infused her work that her obituary, back in 1966, noted that, “[she] used her poetry to combat racial prejudices and hostilities.” Unsurprisingly, political commentary ran through her fiction as well.

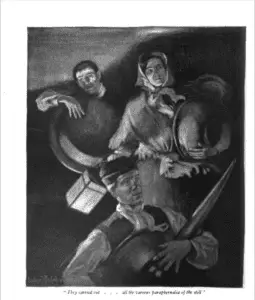

Herron wrote ‘The Still of Ballywan’, her first piece of published fiction, while still a sophomore at Stanford. McClure’s Magazine then picked it up for publication (p. 266). ‘The Still of Ballywan’ follows a group of nineteenth-century Irish peasants as they try to hide their priest’s illicit whiskey still. With ruthless English revenue officers on their way, the characters race against the clock and against potential execution. The central characters are Father O’Tool and Eileen Burke, the said priest and the “colleen” who keeps her head. Their actions propel the story forward: the priest lures the officers to the Bog of Ballywan while Eileen leads her two fellow countrymen, Rory and Tirence, in hiding the still. When the officers finally arrive, they arrive right after Shane O’More, the neighbor who had reported O’Tool. Eileen and Rory make quip remarks to throw off the English and the Orangeman. She also subtly manipulates them, discrediting Shane to prevent any more investigations. The story thus ends positively, though it also ends with a brief meditation on loyalty, unjust laws, and allyship.

With all of that in mind, Herron’s characters read more as impressions or archetypes than fully-realized people due to the story’s brevity and focus on action over psychology. (The story also came out when modernism was still in development, before the shift from an omnipresent narrator to more interior-based narrators and protagonists fully took hold.) She works this shallowness to her favor though. The numerous cultural allusions speak to a world much more complex than what her American audience knows. The shallowness is also reminiscent of the character depth seen in folk tales and the homeland stories that her parents presumably told her.

At its core, ‘The Still of Ballywan’ is the story of a community’s resistance, not that of any particular character’s.

Living in a two-room house, Father O’Tool is a poor priest with a poor parish, whose members have just avoided another potato-based famine. The still is for the community: it produces fiery Irish whiskey, symbolic life force for the people as it reminds them of their heritage separate from English rule. “Usquebaugh”, the Irish term for whiskey, even comes from Gaelic as ‘water of life.’ Herron cements this connection at the beginning of the story when Eileen rouses the men into action: “‘Tisn’t enough that they take your country an’ your governmint [sic] an’ your lands — but they have taken th’ spirit out o’ your bodies,” (p. 267). “Spirit” is clever wordplay on the cultural and psychological significance of the still’s product. Of all the things she listed, the whiskey is consumable, and thus the most connected to the body. By having to purchase English-stamped and approved Irish whiskey, the characters face distilling themselves through the law and the eyes of those who colonized them. Assimilation comes with temporary safety and security, but it does not protect the marginalized nor empower them to be themselves.

(It’s even a little meta, because Herron, who fought for women’s voting rights so they could be more equal to men, was still marginalized. She was forgotten by history, even though she received numerous acclaim throughout her life. Assimilation will carry a person forward, but it can also render them invisible within the system.)

Herron incorporates specific dialect and (mis)spelling cues to color her characters’ speech and to distinguish them from the English. She grounds them in a rural, working-class style that does take a little focus to decipher. It then flows easily enough. The effect calls to mind Zora Neale Hurston’s dialect for her characters in Their Eyes Were Watching God. Terms like “usquebaugh” (p. 266) and “alembic” (p. 269), as well as several references to real places in northeastern Ireland, are sprinkled throughout the text. She also mentions banshees and leprechauns, reinforcing the mythological, Gaelic-based spirituality that formed Irish heritage.

Overall, Herron produced a witty story with sociopolitical tension simmering just below the surface. Eileen Burke also stands out as a proto-feminist character whose cleverness, patriotism, and will drive most of the tricks pulled to protect the still and her people. (Though her speaking for Tirence, a stutterer, has potentially thorny implications that are for a different discussion.) She’s a great example that in the history of storytelling, there have always been proactive women — often created by women writers.

Snow:

I first read ‘Snow’ as a senior in high school. It was my second year taking an AP English course, so I had grown accustomed to dramatic literary fiction and depressing endings. ‘Snow’ was, in her own words, a gift from my teacher. Though I will not go into its exact ending, I will say that it is warm-hearted and fitting for its seasonal setting.

‘Snow’ debuted in the 1991 Fall issue of New Orleans Review (p. 28). Then Butler, a Vietnam veteran and Putlizer-prize winner, republished the story as part of his collection, A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain, in 1992. Butler is American, but he traces most of his influences personally and creatively to Vietnam and the period he was stationed there. He’s even fluent in the language. From what I’ve read of him and from reading ‘Snow’, he does not speak for Vietnamese people but rather sympathizes with their struggles. He aims to show the country’s inherent beauty to his Western audience.

The story reflects its postmodernity due to its interiority. Narrated by Miss Giau, a Vietnamese immigrant living in Louisiana, the story takes place at a Chinese restaurant refashioned from a former plantation home. ‘Snow’ focuses on the two nights that she handles Mr. Cohen’s order. The four-page story is retrospective and wistful, with one of its first lines being, “Did he watch my eyes move as I dreamed?” (p. 28). They meet on Christmas Eve after Miss Giau wakes up from a nap, and the situation has great psychological resonance for her. She had just woken up from sleep, while on a quiet shift at a different Chinese restaurant and on another Christmas Eve, to the first snow she had ever seen. She was terrified by the white mass as it smothered the world around her. It is this dislike of snow that first allows her and Mr. Cohen to bond.

The fact that I remembered this story so fondly years later speaks to its heart and to Butler’s skills. He infuses sensory detail into the text and brings to life for readers the muggy, stifling setting. My whole class even sighed from shipper-y feels thanks to the characters’ banter that sparked in the story’s second half. If I had to describe the story, it would be as a wintery waltz.

Because of her inner thoughts, Miss Giau introduces herself as a complex character, whose contradictions reflect her cultural heritage and diaspora. She ruminates on the disconnect between fellow Asian immigrants and her own disconnect with fellow Vietnamese people in her community and her failing to assimilate. She wonders about the Chinese restaurant-owners as, “They go off to themselves and they don’t seem to even notice where they are,” (p. 28). She sees herself as an outsider because, “Maybe the others are real Americans already,” (p. 28). Her relationship with Mr. Cohen helps her reconcile this diaspora with the expectation to Americanize; he has no judgements of how she should live as an immigrant, of how she should participate in the dominant culture.

Because of her inner thoughts, Miss Giau introduces herself as a complex character, whose contradictions reflect her cultural heritage and diaspora. She ruminates on the disconnect between fellow Asian immigrants and her own disconnect with fellow Vietnamese people in her community and her failing to assimilate. She wonders about the Chinese restaurant-owners as, “They go off to themselves and they don’t seem to even notice where they are,” (p. 28). She sees herself as an outsider because, “Maybe the others are real Americans already,” (p. 28). Her relationship with Mr. Cohen helps her reconcile this diaspora with the expectation to Americanize; he has no judgements of how she should live as an immigrant, of how she should participate in the dominant culture.

As evident by his name, Mr. Cohen is Jewish, specifically a Polish survivor from World War 2. (Miss Giau never notices an accent, indicating his decades-long immersion, as she does not take him for an immigrant.) He surprises her when he mentions his Jewishness and not celebrating Christmas. In Vietnam, everyone celebrates the big holidays regardless of religion, similar to American society and the all-encompassing white, Christian influences. His rejection of the dominant culture makes it easier for them to form a relationship because they can fully bond as immigrants without the pressure of being an “American.” Mr. Cohen is an American, but that identity interacts with his identities of being Polish and being Jewish, the latter having a history and culture of migration already.

In the introduction for Christmas Stories from Louisiana, editor Dorothy Dodge Robbins summarized the characters’ connection as, “exhang[ing] conversations in lieu of presents on Christmas Eve,” (p. X). That insight goes straight to the heart of intimacy that can be forged through honest self-expression and freedom from expectations. No one needs to be liberated from presents, but that is because we choose the wrappings ourselves and the wrappings are permitted to come off. Liberation encourages the safety and security of assimilation while disavowing and destroying the violent structures that required assimilation in the first place.

Overall, ‘Snow’ left me with a deep craving for Chinese food, a snowy Christmas Eve, and someone with whom I can waltz.

Conclusion:

‘The Still of Ballywan’ resonates for its humor and its political subtext; ‘Snow’ endures because of its wonderful character connections and resolutions of comfort. I am not the only one to think so, due to the stories’ republication in different collected volumes. As time marches forward and change moves along in a cycle of progression and regression, the subjects of subjugation change too. A century ago, for example, Irish-American citizens still remembered the nineteenth-century scars from the Great Hunger, British rule, and the prejudice that their parents and grandparents faced when they immigrated to the United States. They were part of the ‘Other.’ Now Irish-Americans have fully moved into the concept of ‘whiteness.’

Looking at history, one can see how ‘whiteness’ never truly included all people of European descent. This social construction transmutes in order to accommodate certain groups with power and privilege, centering a normal against the ‘Other.’ Such a cultural tension exists for Jewish-Americans of European descent, and due to the rise of fascism and anti-Semitism in the past few years, that tension has become even more dangerous.

I was originally inspired to write this review because of the ending line in ‘The Still of Ballywan’, which I must spoil because of its brilliance and relevance to today’s sociopolitical crises: “A lie, Tirence, told to a revenue officer,” said Father O’Tool wearily, “is music in th’ ears of God,” (p. 274). Over the past three years, particularly the latter half of this summer, my news feeds have been filled with headlines about white supremacist violence, ICE raids, and concentration camps. US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) perpetrate human rights violations. Not only have thousands of migrant children been separated from their parents, several children have died due to medical issues caused by custodial conditions. Border patrol agents even imprisoned young American citizens, both of whom had documentation, revealing the racism inherent to this zero tolerance policy. Yes, these migrant people have sometimes entered the country illegally, but helping refugees who seek asylum is our country’s legal duty per the Geneva Convention. Sometimes morality supersedes illegality. In Herron’s story, her characters broke the law as a way to subvert colonial restriction of their culture. In the real world, indigenous people flee their homelands, which Europeans colonized and which our country helped to destabilize over the past hundred years, just so they and their families can survive. Notably, thousands of Jewish-American activists have also protested ICE and connected organizations this summer. One of the leading groups is Never Again Action, whose name refers to the anti-Semitism of the 30s and 40s. They are drawing direct parallels to the anti-immigration and racist sentiments flourishing today.

“A lie told to a revenue officer is music in the ears of God.”

Take “revenue officer” and replace it with “ICE agent” and we have a rallying cry for activists everywhere. And like any good piece of short fiction, a political statement should be minimalist and to the point.