Here at the Fandomentals, we believe in the power of stories. Stories can be amazing tools to explore difficult topics like trauma, since they allow us both a careful look at the issue and to keep our distance from something that may otherwise hit too close to home. A story that handles the subject skillfully can broaden our understanding of it, debunk harmful myths, and empower people struggling with their own traumatic experiences.

Unfortunately, not all stories do that. Storytellers love shocking events or emotionally stressful situations, but they’re not always interested in exploring the aftermath. Of course, there’s no monolithic response to trauma and each recovery process is unique, but there is always some response. Stories that fail to show any reaction to traumatic experiences or only address it when convenient for the plot not only break our suspension of disbelief but also perpetuate false notions on trauma, PTSD, and the people suffering from it.

How can stories address trauma more thoughtfully and respectfully? There’s no single answer for this, but I’d argue we can learn a lot from stories that are doing it right. The current run of Hulk (2016), written by Mariko Tamaki, is one such story.

What Hulk did right

Starting December, 2016 and currently on its 11th issue, Hulk (2016) deals with the aftermath of the second superhero Civil War for Jennifer Walters, better known as the She-Hulk.

During Civil War II, the She-Hulk was mortally wounded in a fight against Thanos, falling into a coma. Upon waking up, she discovered that her cousin Bruce Banner, the Hulk, was killed by fellow superhero Hawkeye. So, Hulk (2016) picks up shortly after that, when Jennifer resumes her work as a lawyer.

The story had two major arcs so far, exploring Jennifer’s PTSD and recovery along with the usual superhero threats. Her antagonists in both arcs were people handling traumatic experiences of their own, though in levels that required superheroic intervention.

There are several merits in how Hulk (2016) approaches the themes of trauma, PTSD, and coping with loss—there are also flaws, but overall their record is solid. This analysis is by no means extensive, and I recommend you to check the comic for yourself in case you haven’t already.

So let’s have a closer look at what it got right and why.

Symptoms and Depictions

The comic book presents an honest depiction of trauma and PTSD. Through the entire first arc, we see Jennifer struggling with anxiety, triggers, flashbacks…the whole package. Those arise from different situations and in varying intensities. Sometimes the usual coping strategies don’t work. Sometimes a good day can quickly turn into a bad one.

“Like I’m walking away. Like this is anything I can run from. It’s there, it’s here, it’s always here. I’m holding it together with both hands but it’s too much.” (Jennifer Walters in Hulk 2016 #1)

There’s a strong anxiety in getting back to work, with her inner monologue constantly reassuring her that “it’s gonna be fine,” her heart pounding, and Jen feeling like throwing up. Even the briefest mentions of the superhero Civil War or what happened to Bruce impact her, in some cases causing her to feel angry, anxious, or sobbing on the floor unable to do anything. She can’t stop thinking about what happened and, paradoxically, she avoids delving into her own feelings on the matter. All the time we get this sense that she’s no longer who she used to be and that her trauma has negatively impacted how she sees the world around her.

Even as she starts to recover and those symptoms decrease in frequency and intensity, we still see her struggling with them.

“Rage and suffering. In the heart of the monster, one feeds the other. In my monster heart, sometimes…it’s all I can hear” (Jennifer Walters in Hulk 2016 #10)

Identity

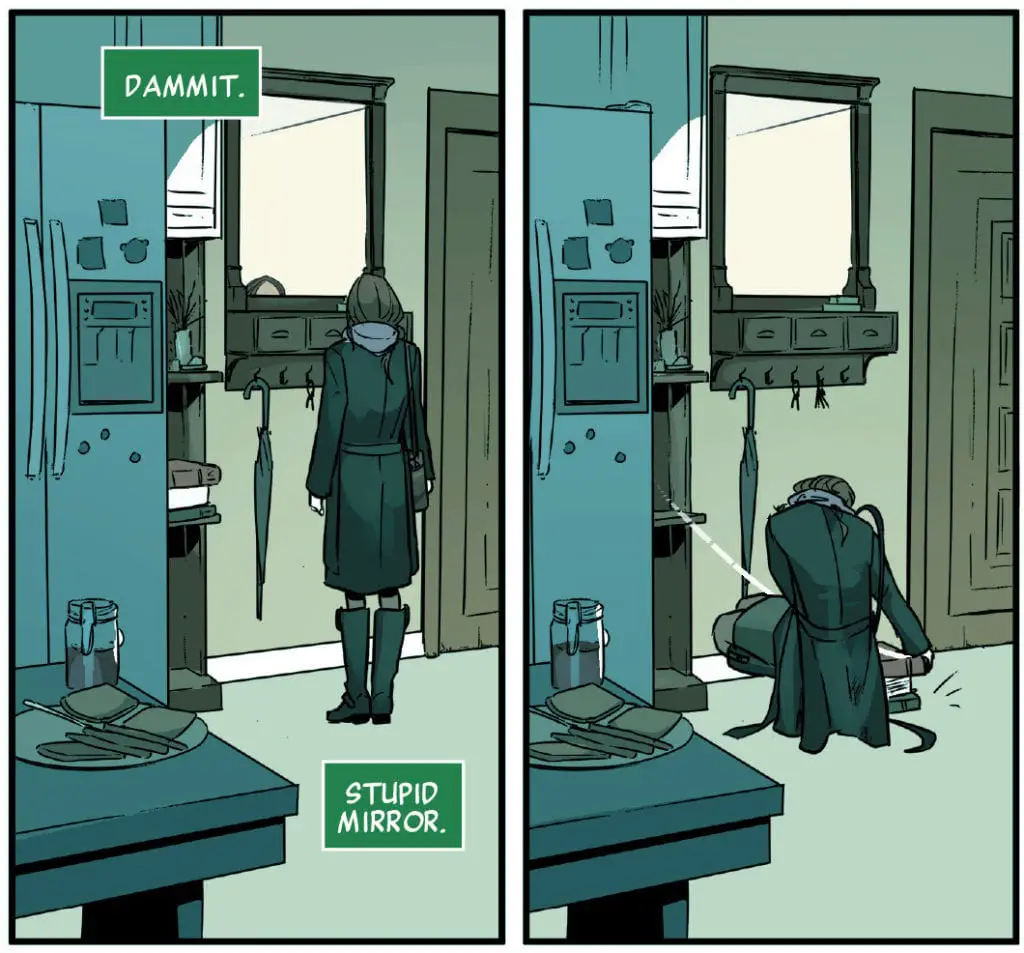

Before Civil War II, Jen was known for feeling comfortable with her Hulk persona. Unlike her cousin Bruce, she could control the monster within and derive emotional strength from it. Her life was tailored to be lived in Hulk form and we can see that even in small details, like how her entire apartment is built to fit a Hulk-sized person and not a regular woman:

Yet for nearly the entire first arc, Jen was unable to become the Hulk again. Being a Hulk was empowering for her before, yet now:

Her struggles to reconnect with her Hulk persona work as a metaphor for how much we change after traumatic experiences. We’re different than before and we feel like we lost something of ourselves in the process. Because here’s the thing about trauma: there’s no going back. We can cope, we can recover, we can have amazing and fulfilling lives even after horrific experiences. But we can never go back to how things were before.

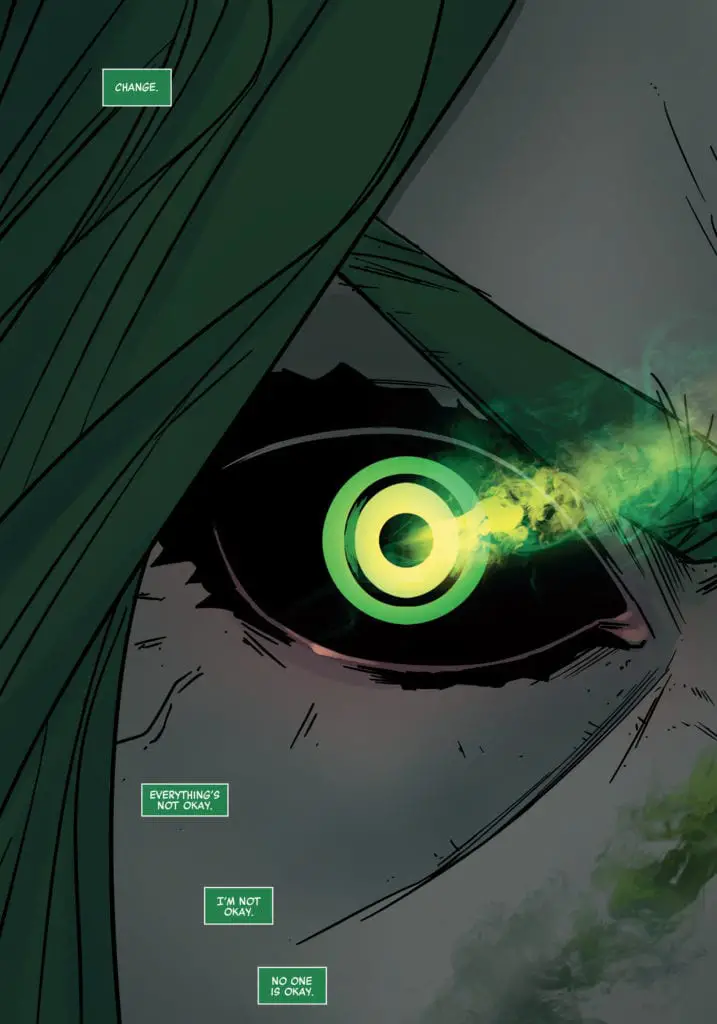

So it’s an interesting choice that even after Jen is able to become the Hulk again, she becomes a different Hulk. A Hulk she doesn’t completely control or understands. A literally scarred Hulk.

It’s very fitting that she then assumes the title of Hulk, not She-Hulk. The old Hulk is dead, the Hulk that was so close to her and so meaningful to the origin of her powers. The old She-Hulk is dead too, in a way. This is a new monster, and one that in many ways resembles Bruce’s savage Hulk more than who Jennifer used to be.

“Are you doing this for Bruce? Maybe I am. Maybe everything will be for Bruce now. You have a problem with that? Obviously I don’t Jen, since I’m you. I mean, not everything is for Bruce. Just these things. These things that make me mad” (Jennifer Walters in Hulk 2016 #8)

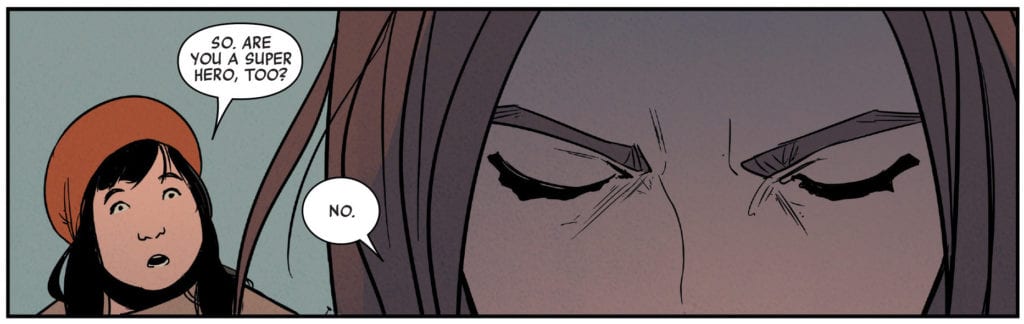

Struggling with her Hulk form also means struggling with being a superhero, since both identities are so closely associated. There’s a certain guilt in not being out there doing something “at least a little bit super.” Amidst so many losses, Jen also loses core elements of her identity and sense of self.

Isolation and Support

Through Jen’s journey, we see the sense of isolation that trauma and PTSD can cause.

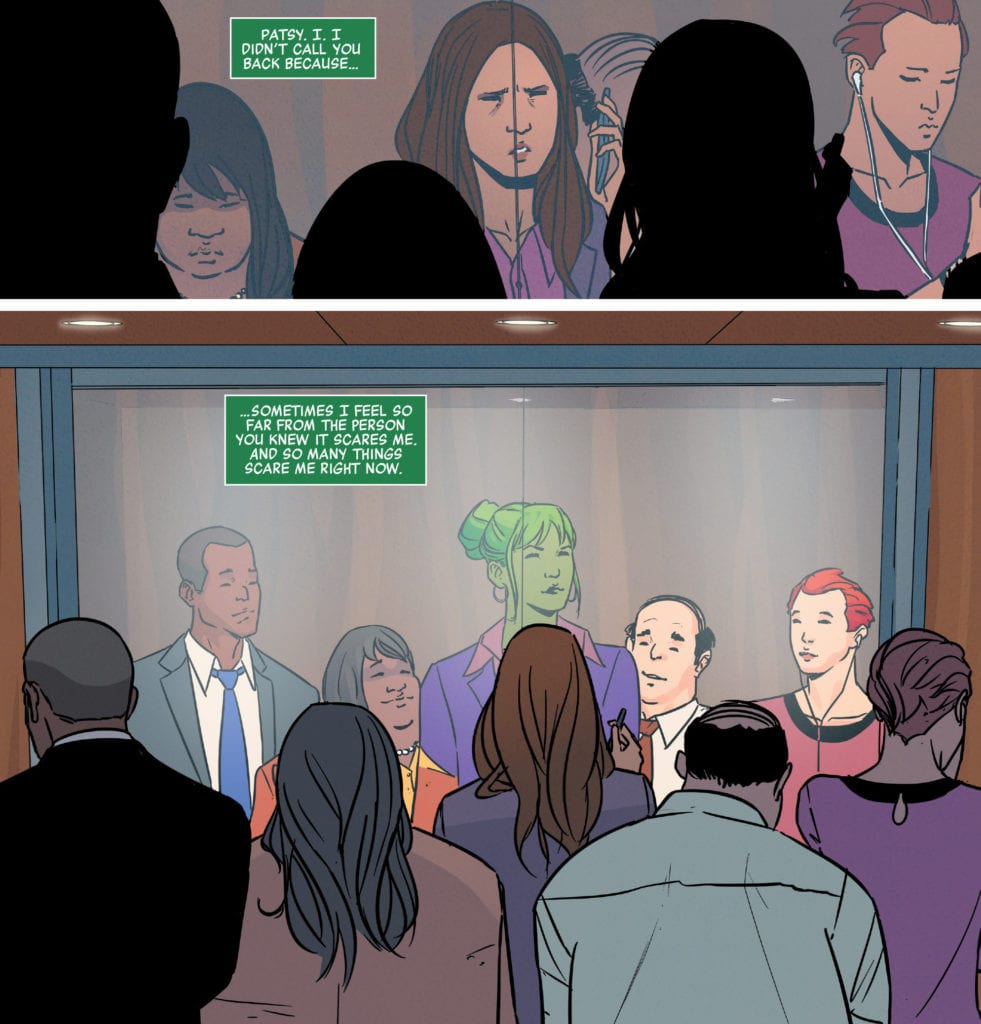

“A really awkward conversation with a friend is a good indication that the universe is not what it was. At least for you.” (Jennifer Walters in Hulk 2016 #5)

There’s the constant feeling that people around Jennifer don’t know how to reach her or how to behave towards her. They don’t know how to approach what happened and Jen is not exactly receptive, creating a gap between her and others. Jen explains her own position well:

But of course it’s more complicated than this, and we see it when Patsy decides it’s best to give Jen more personal space. She adds that she’s not disappearing, and Jen replies that she’s counting on that. There’s a desire to avoid others, but at the same time there’s a desire for more proximity, too.

Missing Bruce is key here. Now that being the Hulk poses a challenge, Jen believes that Bruce could understand the feeling better than anyone else. Again, something previously so empowering as being the Hulk enhances the feeling of loneliness.

Not for nothing that we see the sidekicks growing in presence and importance as Jen slowly recovers and begins to reconnect with other people.

Recovery

Recovery from trauma can be slow and painful. Stories tend to rush this part; suddenly a traumatic experience no longer impacts the character, as if it never happened at all. Hulk (2016) doesn’t do that, showing sensibility in how to write the recovery process too.

Perhaps my favorite aspect is how the story shows that a recovery process is not always linear. You have good days and bad days, and sometimes it seems like you’re doing great until you’re not. Every small progress should be celebrated, but it doesn’t mean the battle is over. As Jen puts it,

“You can feel like you’re falling apart one minute and then feel like eating pizza.” (Jennifer Walters in Hulk 2016 #2)

As the story goes on, we can see Jennifer slowly change. She’s able to transform into the Hulk again. She allows other people to get closer. Her mindset becomes somewhat less pessimistic and gloomy than before. Perhaps her biggest step is to admit that she needs recovery in first place. She starts the story by saying that it’s “other people” who sit in their houses “wallowing” and “recovering,” not her. So it’s quite meaningful that her first post-trauma Hulk transformation happens when she admits that she’s not fine:

After that, we see small but important steps in looking for help, such as trying a trauma support group. Yet her biggest coping strategy is to become the Hulk and tear down an abandoned construction site, which is quite a raw, primitive way to get in touch with your feelings. It’s also a telling choice: once again being the Hulk is a vital part of Jennifer’s empowerment.

Even as Jen gets better, the story never gives you the feeling that her recovery process is over. It doesn’t drop the importance of her trauma after the first arc, and it doesn’t return to the old state of things, even though it’s heading to a new state of things. There’s this sense that part of her trauma will always be with her, she’s just learning how to handle it better.

How Hulk did it right

I pointed to elements in Hulk (2016) that I think do justice to a topic as complex as trauma. But why is this story getting those elements right when so many other stories don’t?

Finding the right writer seems a vital step to me. Mariko Tamaki, the writer behind Hulk (2016), has a long history with stories that focus on character’s inner lives, including difficult topics like depression and grief. I haven’t checked her previous work yet, but the choice makes sense. If you want to approach delicate issues with the attention they deserve, you’ll want a writer that isn’t afraid to explore them but does so with skill and sensitivity. You can tell there’s a lot of effort in creating a thoughtful depiction.

The story is allowed to breathe and develop, much like its protagonist. Hulk (2016) isn’t afraid of slowing the pace if that means properly exploring Jen’s experiences and recovery. This results in a slower and more introspective story, which may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but feels very adequate to the themes involved.

The comic book format proves to be an excellent one to explore the subject of trauma. The art illustrates much of what’s going on with Jennifer without the need to say it outright, with choices as simple as color palettes helping set the mood of the story. Jennifer’s inner monologue, a style of narration so common in comic books, is vital to show the reader how she’s processing everything without the need to disrupt the main action.

Above all, it’s an entertaining story. At the end of the day, that’s still what we’re looking for: well-written and interesting stories, that work on a narrative level. Hulk (2016) never loses what makes comic books appealing, while also providing a solid examination on a topic so often mishandled in fiction.

Overall thoughts

Just in case you’re wondering, I love how this comic approaches trauma. It’s refreshing to see this much skill and effort, and I expect it to continue to adress Jennifer’s recovery in a realistic way (or as realistic as grey monsters allow).

I do worry about the future, though. There was a great emphasis on how much trauma changed Jen, so it would feel cheap to dismiss it, even after a period of time. We can still have a lot of what we love in classic Jennifer Walters and her Hulk self while not ignoring what should be a major event in her life.

Sadly, comic books are infamous for their impermanence, especially if the people behind them change. What will Marvel Legacy mean for Jennifer? Legacy is a return to the old: the original series numbering. And, more importantly, the old title of She-Hulk. There was a narrative point in her being called just Hulk, so hopefully those will be just details and not a sign that the story is shifting too dramatically. As Tamaki so aptly showed us, from certain things there’s no going back, only forward. I’m glad we still have her behind this story.

Whatever happens, we still got an entertaining story that addresses trauma thoughtfully and respectfully. That’s no small feat.