It’s a fairly common trope in fantasy and science fiction to wrap a message about systematic oppression in magic and superpowers to create an oppression allegory. The why is obvious: it’s fun to talk about magical people being mistreated by non-magical people. Rather, it’s more fun than talking about literally any existing system of oppression. Besides, this trope automatically gives real-life outcasts role models who are cool as heck. They’re especially cooler than the “normies” who resemble the real-life societal bullies. And I won’t deny that these allegories can be useful, particularly with young audiences. The horror inflicted on people designated “other” is much easier to swallow when it’s a few steps away from reality.

But I’ve always felt there were two fatal in oppression allegories wherein the magical or superpowered people are the ones oppressed: they make no sense and they don’t have the teeth they could have.

What do I mean by this?

Look at BBC’s Merlin, a re-imagining of the Arthurian Legend. In the first episode Merlin moves to Camelot because he’s a born “sorcerer” and his mother Hunith is not. Camelot’s court physician, Gaius, is an old friend of Hunith’s and a bit of a sorcerer himself. Hunith and Merlin are hoping Gaius take Merlin under his wing. The problem? Magic is illegal in Camelot. In fact, King Uther (Arthur’s father) has carried out a genocide against sorcerers. Oppression allegory set.

And Merlin is far from alone. The X-Men franchise, Leigh Bardugo’s Grishaverse novels, and Ransom Riggs’ Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children can all be read as oppression allegories. The protagonist of Miss Peregrine’s, Jake, is the grandson of a Holocaust survivor. Jake meets the title Peculiars while visiting the town his grandfather fled to after the Nazis invaded Poland. Magneto, a major villain/antihero of the X-Men franchise, is a Holocaust survivor who wasn’t able to flee. The Grisha of Leigh Bardugo’s novels are enslaved, tortured, or killed everywhere except Ravka. In Ravka they’re impressed into the army instead.

What I want to know, though, is how guys with swords and chain mail beat guys who can set things on fire with their minds. Why the Peculiars have to hide. Why can’t they just go “Hey, some of us can bend time, back off.” And so on.

“Yeah, but you see…”

All of the stories I mentioned, and most oppression allegories in general, at least try to explain themselves. The Peculiars of Miss Peregrine’s are mostly children. They’re also woefully outnumbered and some of their enemies are their fellow Peculiars. The X-Men are also mostly children (for the first few movies anyway) and also outnumbered. And in Days of Future Past they have to face Sentinels, robots that can adapt to any and all of their powers. In Leigh Bardugo’s Grishaverse, each grisha order has a specific weakness. Heartrenders can’t hurt you if they can’t see you, for example. Plus, the grisha live in a world where guns are the hot new thing.

The Alternative Oppression Allegory

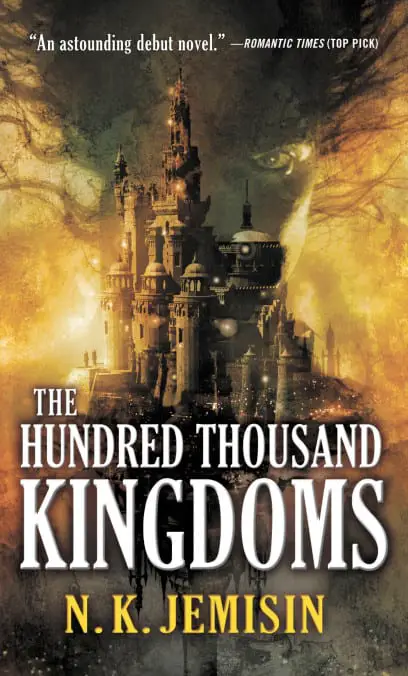

I’ve always thought, why not flip it around? Why not have our hero be a normie? Someone without cool abilities surrounded by people who do have them? Someone who would be an underdog even in the real world? One such story is The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms by N.K. Jemisin.

In The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms we meet Yeine Darr, the product of a scandalous marriage between a member of the imperial dynasty and a minor ruler. In the beginning of the book, Yeine is unexpectedly summoned to her grandfather’s court to be made one of three heirs to the throne. Why three heirs? Because grandpa wants to have tryouts.

From then on, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms develops into a highly effective allegory of imperialism. Part of the reason it’s so effective is because it’s barely a metaphor at all. The ruling dynasty, the Arameri, are almost entirely pale, blond, and blue-eyed. The people they rule over are none of these things. Practicing any religion other than the one the Arameri prefer is illegal. There are “darkling races.” Ringing any bells?

I don’t want to spoil too much of The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms for you, but suffice to say that the Arameri gained the power they did by having better magic than everyone else. That’s it. Magic is all but outlawed unless it’s under their control somehow, and as a result, they can bend the entire world to their will. So, our hero, Yeine, is up against impossible odds that are actually impossible. She isn’t Merlin, or a grisha heartrender, or a mutant, or a peculiar. She’s just Yeine.

And yeah, it’s a fantasy novel so Yeine’s not quite what she seems. Still, she doesn’t spend her days setting things on fire with her mind while wondering how she could ever possibly overthrow the evil government. In fact, it’s made pretty clear to us from the jump that Yeine is doomed.

To me, that’s something. In subverting the common trope, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms actually manages to tell the story of an underdog who triumphs against impossible odds. Telling outcasts that they’re as cool as the girl whose looks can actually kill is nice. But it’s also nice to tell the real-life underdogs that they don’t need superpowers to be special. That they can “win” against something or someone far more powerful than them.