Spoiler warning for The Hunger Games trilogy and its movie adaptations.

This is a difficult piece for me to write. Not because it is a struggle to articulate my viewpoint or find evidence to back it up, but because The Hunger Games trilogy (THG) is my favorite media franchise ever. Katniss Everdeen is arguably my favorite fictional character, even though she drives me nuts at times. While there are many things to love about the series, especially in terms of its exploration of gender roles, Katniss is what makes the story stand out.

Truly, series author Suzanne Collins wrote one of the most interesting young female protagonists of our time. Katniss is engaging and inspiring for young women, all while occupying quite the intersectional identity. She was born into poverty, is functionally biracial, and is arguably implied to be somewhere on the asexual, aromantic, and autism spectrums. The depth and development in Katniss’s character is extremely impressive, and I am very thankful to Collins for that. But as the title suggests, I do have a few critiques of the series as written.

Before diving into this analysis, it must be acknowledged that THG was not necessarily meant to be a feminist piece of literature. While Collins did some novel things with gender representation in the books, they are not about that. At its core, THG is a story about war and its effects on young people. It has as much commentary on mental health as it does on gender politics. So this perhaps feels a little like splitting hairs, focusing on the wrong things. I’m going to do it anyway, because this is a conversation I have seen happening online for years, and I think it’s missing some key points.

There is good reason why people consider THG to be a feminist piece of media. In many ways, it is. In terms of more obvious issues regarding female representation and the unfair expectations of us, it delivered. Unfortunately, some more insidious problems with our society’s gender narrative were ignored or even played into. The series made some great strides in the right direction but was tripped up by subtle gender issues we are only starting to parse out now. It must be acknowledged that the books were published from 2008-2010, and we can’t expect authors to predict the discourse happening five, ten years down the road.

Because they are the core of the story and contain the most detail, this analysis will mainly focus on the books. However, there will be references to how THG was adapted to the screen and what it says about the story. And while I do have critiques to add to this conversation regarding the feminist content of THG, there is much to praise as well. Let’s start with that.

What THG did right

I don’t have room to discuss all the good things Suzanne Collins did with THG, or at least tried to do. As mentioned, Katniss is an intersectional character in many ways, and at least some of those intersections are explored. This was before intersectionality was a household term, making it even more impressive in my humble opinion.

Even the intersections that aren’t explored raise questions to ponder. For example, if the Seam people are considered to be their own race then Katniss’s sister Prim is a white-passing biracial girl who was raised in poverty surrounded mostly by people of color. I would have been very interested to learn more about her experiences. How she identifies, how she is treated by her neighbors and by the slightly less poor “blonde and pale” merchant class she resembles. Their differing appearances seem to cause no friction between Prim and her sister who is more obviously a PoC, but they are family after all.

THG tackles a number of moral issues as well, as war stories tend to. I appreciated the moral arguments and the acknowledgement that things are more complicated than they seem. How relative is morality, and how relative is privilege? THG’s explorations of privilege and the perception of privilege were nuanced and valuable to our cultural discourse, and it’s a shame they have been largely overlooked. And unfortunately, Gale Hawthorne’s righteous anger at his own oppression devolving into moral relativity over taking innocent lives has not been taken as the warning it was no doubt intended to be.

Gale’s arc echoes the indiscriminate quest for justice/vengeance that drove the humanitarian disasters of the French Revolution and Rwandan genocide. I never much liked him, and this is part of why. While Katniss is surprisingly good at critiquing her own perceptions of others, Gale refuses to do so. Ultimately, it costs him his humanity. He is a cautionary tale to angry young people if ever there was one. And in this day and age, we could use that.

So, yes, there is much to gush about regarding THG. To keep this piece on topic and a manageable length, however, from now on I will stick largely to issues of sex/gender. Here are some things in particular that stood out to me in the series.

A fleshed out and relatable female protagonist

In a sea of paper-thin stock love interests and Strong Female Characters™, Katniss Everdeen is a refreshing dose of reality. She is a character you can analyze to death because there is so much there to dig into. And yet, while she is characterized very specifically and is far from being an everywoman, women and girls the world over relate to her. This probably speaks to the lack of relatable female characters let alone female role models in our media. While she’s far from a role model in some respects (which is good), Katniss has agency of thought if not action and has a story that does not revolve around a love interest. Yes, there is the love triangle she has to deal with, but it’s not that important to her. How novel that is is depressing.

As an aside, let me clarify that remark about agency of thought versus action. One complaint I sometimes see is that Katniss lacks agency in the sense that she is constantly being manipulated and lots of her choices don’t end up mattering. It’s a fair point, but I think that ties in better with the themes of the devastation and politics of war. To me, that has nothing to do with her gender and everything to do with the larger themes and messages of the series. And even when her choices don’t matter, she makes them. She is determined to choose her own path, and to me that looks a lot like agency.

Circling back now, my reasoning for being happy that Katniss is not perfect is that, frankly, we have enough perfect women in media. Maybe it’s meant to be a compliment, but it perpetuates unhealthy gender stereotypes. There is a severe dearth of female antiheroes out there, but Collins wrote a great one. Katniss cares deeply about some people but can be incredibly self-absorbed, recognizing the needs of no one but her small inner circle. She notices problems in the world but is a reluctant hero, not wanting to risk rocking the boat and making things worse or putting her loved ones in danger. Her problems may exist on a grander scale, but her moral dilemmas are relatable.

More personally, Katniss is a snarky, cynical little a-hole and I love her for it. Her narrative voice is incredibly relatable to me, another taciturn female full of silent sarcastic barbs. Behold two of my favorite narrative quotes:

If I feel ragged, my prep team seems in worse condition, knocking back coffee and sharing brightly colored little pills. As far as I can tell, they never get up before noon unless there’s some sort of national emergency, like my leg hair.

–Catching Fire

—

At some point, the train stops. Our server reports it will not just be for a fuel stop — some part has malfunctioned and must be replaced. It will require at least an hour. This sends Effie into a state. She pulls out her schedule and begins to work out how the delay will impact every event for the rest of our lives.

–Catching Fire

My ultimate point here is that representation matters. When so many female characters feel the same in terms of personality and goals as well as identity, it can be hard to connect with any one in particular. These days we are definitely seeing more diverse female representation in the media, and maybe Katniss was part of what sparked that. She caught the attention of women, and maybe that caught the attention of content creators and was part of the impetus to diversify female representation. I like to think so, anyway.

Critiques of the modern conception of femininity

THG scored some serious feminist brownie points by addressing the double standards women have to deal with in terms of presentation and the way we can be squeezed into boxes that don’t fit. Katniss is clearly uncomfortable with having to play the giggly girl in love. Even before that, her interview prep session with Effie is disastrous because she struggles with how to present as feminine, especially in the fancy way that will be required in that situation.

I’ve never worn high heels and can’t get used to essentially wobbling around on the balls of my feet. But Effie runs around in them full-time, and I’m determined that if she can do it, so can I. The dress poses another problem. It keeps tangling around my shoes so, of course, I hitch it up, and then Effie swoops down on me like a hawk, smacking my hands and yelling, “Not above the ankle!” When I finally conquer walking, there’s still sitting, posture — apparently I have a tendency to duck my head — eye contact, hand gestures, and smiling. Smiling is mostly about smiling more. Effie makes me say a hundred banal phrases starting with a smile, while smiling, or ending with a smile. By lunch, the muscles in my cheeks are twitching from overuse.

–The Hunger Games

The Capitol of Panem is meant to echo our North American society (or at least the upper echelons of it), therefore everything is about appearances. Many of the Capitol citizens are in debt because of this. Further, they are pretty blatantly sexist in the same ways we are. This shows up in how they sympathize with Peeta the lovelorn boy and the pressure Katniss feels to reciprocate, as well as their expectations for how men and women will dress and behave. It’s all about presentation.

“Doesn’t [Peeta] need prepping?” I ask.

“Not the way you do,” Effie replies.

What does this mean? It means I get to spend the morning having the hair ripped off my body while Peeta sleeps in. I hadn’t thought about it much, but in the arena at least some of the boys got to keep their body hair whereas none of the girls did.

–Catching Fire

Katniss is a perpetual fish out of water for most of THG, someone who doesn’t fit into society the way she is supposed to. It can be argued that there is commentary in the story on compulsory heterosexuality and the struggles to present as a neurotypical, depending on how you interpret Katniss’s sexual and romantic orientations and whether you buy into the theory that she is on the autism spectrum. (I am partial to this theory, but I am admittedly biased.) Either way, there is absolutely commentary on the pressure to conform to gender roles, and it’s one of many things I love about the series. That and how not fitting into those roles is not presented as bad or weird, which deserves a mention all its own…

Gender role switcheroos

Katniss Everdeen defies traditional gender roles, and the fact that she does so without really trying makes it even better. As mentioned in the last section, Panem is not exactly an egalitarian society in terms of gender. However, this seems to be less pronounced in the districts, where the struggle to survive takes precedence over anything else. Katniss being a hunter and provider are far from her only stereotypically masculine traits, however. She is a poor conversationalist and generally asocial, has no interest in boys until she is thrust into her unfortunate love triangle, and says she looks nothing like herself when she has to get dressed up for the Reaping.

Perhaps the best way to describe her variance from typical gender roles is to evaluate her in terms of instrumental vs. expressive personality traits. Our society tends to socialize women to display expressive traits such as sensitivity and cooperation. Meanwhile, men are pressured to behave in instrumental ways, which essentially boils down to getting things done and not worrying about anyone’s feelings because they are irrelevant to the task at hand. Katniss either missed or ignored this socialization process and is instrumental to a T. One can be a mix of instrumental and expressive, but she is not. She’s downright terrible at understanding let alone expressing her own feelings, much less sensing and showing concern for others’. Unfortunately, she is still saddled with the emotional labor of making boys feel better and this is never critiqued, a point I will get to below.

Peeta, meanwhile, is more expressive in both personality and role and is a rare example of a male suffering empath. This is what makes his relationship with Katniss so unique. As this classic article posits, Peeta fills a traditionally more feminine role in relation to the hero. He is moral support and physically capable of fighting, but ultimately the one who always needs to be rescued. And it doesn’t feel like a contrived and heavy-handed reversal either, because Collins didn’t have to emasculate him to pull this off. Peeta’s physical strength is one of his greatest attributes. His weakness in battle comes from a lack of situational awareness and actual combat skills, both of which Katniss has in spades.

This is not to say that gender roles are swapped across the board in THG, and it would be weird if they were. Gale is definitely more traditionally masculine than Peeta in terms of occupation and personality. Cato’s hypermasculinity is arguably his greatest weakness. On the other hand, Alma Coin is calculating and ambitious, and under his careless and cocky facade Finnick Odair turns out to be sensitive and empathetic. He also uses his sex appeal to his advantage (though Johanna did the same thing) and is a male rape victim.

Male rape victims can make really good stories if done well, and I would argue Finnick’s was. Katniss’s initial judgements about him turn out to be false when she realizes he was forced into his array of sexual relationships with the Capitol elite. While silently judging him for sleeping around she also assumed he wanted to, which is interesting commentary on our society’s perception of gender and sexuality. If there was a female in a similar position who Katniss was close to, we could have really delved into this double standard and how it affects both sexes negatively, but unfortunately there was not. In fact, that’s one of the main issues I had with the series. On that note…

My Fave is Problematic

It’s a sausage fest

Elizabeth Banks had a good point when she joked about how being a female action hero Jennifer Lawrence needed not one but two male co-stars. Lawrence’s remarks in the Catching Fire special features about finally having a girl (Jena Malone, who plays Johanna) around showed a similar frustration/amusement with how male-dominated the series is despite having a female protagonist. Sometimes it feels like this story doesn’t even pass the Bechdel Test, to be perfectly honest. It’s not technically true, but the series is seriously lacking in terms of a female supporting cast.

Beyond numbers, my issue with the female supporting cast is that many of them are static and/or stock characters. I will delve deeper into this in the subsection on influential characters, but suffice it to say that even though Katniss talks to other named females about things other than men, the conversations aren’t as crucial to the story or her development. Women aren’t part of her support system. Plus, many of the supporting female characters lack arcs of their own. (Prim is the notable exception here, though Katniss fails to notice her development at first because she is the ‘younger sibling whom must be protected at all costs’ trope, among others.) Numbers do play a role, though, so let’s start with that.

Who is most present?

To determine just how bad this problem is, I did an analysis of name mentions in each of the three books and in the series overall. This serves as a good litmus test of who is not only present in the scenes, but present in Katniss’s head. For instance, Gale has very little “screentime” in The Hunger Games but is still mentioned over 100 times. Katniss’s guilt over her fake romance hurting his feelings keeps him in the narrative throughout the book. Similarly, Rue dies in the first book but her death haunts Katniss and she is mentioned enough posthumously to still make the top ten overall.

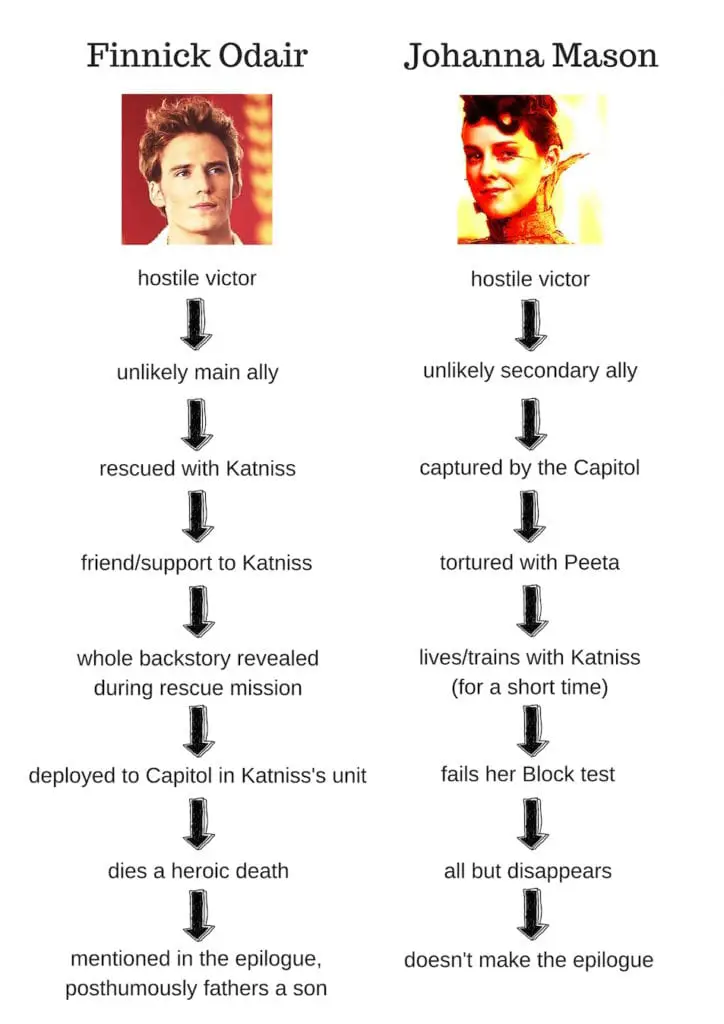

The results are honestly worse than I expected. Mockingjay is particularly depressing, with the seven most-referenced characters being male. Catching Fire features the rise of Finnick Odair, who literally comes out of nowhere to become a major character. He and Johanna Mason start in similar roles, yet he is mentioned at almost 3x the rate of Johanna (more on this comparison below). Even Boggs comes out of nowhere to become influential in Mockingjay, becoming somewhat of a father figure to Katniss and garnering significantly more mentions than any member of her actual family.

Who is influential?

To see just how much men dominate this story, all you have to do is look at the characters who have the most influence on Katniss. Love interest? Male. Best friend? Male. Mentor? Male. Closest confidante in the Capitol? Male. Closest confidante in District 13? Male. Father figure in District 13? You get the picture. While there are females in Katniss’s life who are important to her, they are either children or women whom she doesn’t respect. Katniss doesn’t turn to her sister for any kind of support until Mockingjay and only accepts her mother’s help grudgingly. Rue is mostly fodder for Katniss’s messiah complex, and Katniss doesn’t take Effie seriously. There are no women who truly take Katniss under their wings and help her thrive.

Johanna Mason and Alma Coin are influential female characters, but not in Katniss’s life. She distrusts them both and they dislike her. So much for women supporting women. We get about one chapter of Johanna being important as a friend/ally to Katniss before she is effectively removed from the story. Cressida is the closest thing Katniss has to a female friend or equal during the invasion of the Capitol, and they aren’t even that close. It seems Annie is somewhat of a friend to Katniss post-war but they may just be glorified pen pals. We never have any indication prior to that that they are close at all. Ultimately, Katniss stays insulated in District 12 with Peeta and Haymitch as her company because her mother declines to return after Prim’s death. Her only remaining family at that point is Buttercup, Prim’s tomcat. Yes, even the cat is a dude.

Who is disposable?

The most prominent disposable character in the series is without a doubt Effie Trinket. She mostly exists to annoy Katniss and provide comic relief, and is of so little use outside of keeping people on schedule and spinning PR for the Capitol that she is no longer needed in Mockingjay. Further, her disappearance from the story is hardly mentioned. Katniss mourns Rue’s and Prim’s deaths intensely. Finnick’s death does little but add to the “horrors of war” narrative, but at least he gets a little send off in Katniss’s head. Even Cato’s death is emotional for Katniss, and he was her primary antagonist. Meanwhile, Effie’s possible fate barely crosses Katniss’s mind during their separation. That has a lot to do with how obsessed Katniss is with how she failed Peeta and what might be happening to him, but even after she has Peeta in hand she doesn’t consider Effie’s circumstances.

The films made a good choice in bringing Effie to District 13, allowing her to be more involved in the plot of Mockingjay. Kudos to Elizabeth Banks for bringing that character to life and turning her into a fan favorite. She made Effie less disposable by virtue of the way she played her.

The wasted female character I am most salty about is easily Johanna Mason. She is not necessarily disposable by nature, but she was disposed of. While she could have been used like Finnick Odair and turned from a reluctant ally into a close friend, she wasn’t on screen/paper enough for her and Katniss to develop such a relationship. Also related to Finnick, why was Johanna’s story about losing everyone she loved never explored? It is implied they are dead because she refused to be a prostitute for the Capitol like Finnick, but that’s all it is. Implications. Johanna has clearly been traumatized long before her torture following the Quarter Quell, but that trauma is only hinted at. It takes Katniss ages to realize that Johanna is hurting just like she is and to treat her accordingly.

That being said, Johanna and Katniss do form a bond of sorts. They live and train together in the military for a few weeks between Finnick’s wedding and the failed test that sends Johanna back to the hospital and essentially ends her story arc. Of course, these weeks are largely skimmed over in the text because apparently this relationship is not important. The pair does share a very sweet moment when Katniss makes a sentimental gift for Johanna to remind her of home, but it’s pretty short. However, it definitely is indicative of character development for Katniss that she would do something like that for somebody other than Prim. The same goes for how she volunteers to room with Johanna to help her out.

Another thing I like about this time period is that Katniss gets a rude awakening about her behavior and changes it. She goes from an undisciplined rebellious teenager to a committed soldier once she realizes that that is how she is being perceived and it’s why she is not being taken seriously. Her going through that with Johanna by her side and finally getting that female bonding only makes it sweeter.

However, the fact that the filmmakers could cut that entire subplot without sacrificing the overall arc of the story (only Katniss’s character development, which they didn’t seem to care much about anyway) goes to show that Johanna isn’t crucial to the plot after Catching Fire. She isn’t even in the epilogue, which gives you a pretty good idea how much effort was put into properly closing her arc.

Refer to this infographic below for a comparison between the trajectories of Finnick and Johanna. As illustrated, they start in similar positions but are given very different arcs.

A less prominent but still very obvious example of a disposable female character is Madge Undersee. She only exists to move the plot forward, to the extent that I have alternately dubbed her Convenient Madge™ and Deus Ex Madgina™. She conveniently gives Katniss her Mockingjay pin, conveniently arrives with medicine for Gale, and conveniently disappears when we could have had a chance to get to know her better. Early in Mockingjay, Peeta is inaccessible and Katniss and Haymitch are estranged. God forbid we develop an existing relationship with another woman to fill the void rather than give Katniss a new support network of men in Boggs and Finnick.

Upon Peeta’s rescue, Madge should have been the non-threatening liaison character that helped him reconnect to his old memories. She would have been perfect, being an already established Townie character his age. Instead, Delly Cartwright filled that role. It really makes no sense whatsoever. I can only assume Madge was written out of the story because Collins either a) wanted to add to Katniss’s death/grief toll or b) didn’t want to have to flesh out Madge’s character or her relationship with Katniss. Delly could be kept on the sidelines easier because she and Katniss were not friends prior to Mockingjay. That’s not to say Madge was ever important in the first place. She mattered so little to the story, in fact, that the filmmakers decided to cut her character entirely from the film universe and literally only had to change where the pin and morphling came from.

Katniss is made to feel like she owes the boys who want her

This is honestly the thing about THG that irks me the most. Peeta’s and Gale’s actions (and sometimes their words) suggest that Katniss not being into them is her problem, not theirs. Something that she is doing wrong. Which isn’t really uncommon for teenage boys (or grown men, for that matter). Unfortunately, Collins had a chance to challenge this viewpoint with THG, and instead the storyline reinforces it.

It’s an understatement to say male entitlement is a problem in our society, and it’s on full display in THG. Though they express it in different ways, Gale and Peeta are both passive-aggressive, whiny friendzoned boys. We’ve all known our share. It doesn’t mean they don’t have redeeming qualities, of course. I don’t see Peeta as some kind of saint, unlike much of the fandom, but he is an interesting character and he at least tries to be a good person. But when it comes to Katniss, he can be kind of a dick.

“She’s just worried about her boyfriend,” says Peeta gruffly, tossing away a bloody piece of the urn.

My cheeks burn again at the thought of Gale. “I don’t have a boyfriend.”

“Whatever,” says Peeta.

–The Hunger Games

—

[Gale] pulls away first and gives me a wry smile. “I knew you’d kiss me.”

“How?” I say. Because I didn’t know myself.

“Because I’m in pain,” he says. “That’s the only way I get your attention.” He picks up the box. “Don’t worry, Katniss. It’ll pass.” He leaves before I can answer.

–Mockingjay

Look, we can all relate to the narrative of longing from afar. It’s why everyone and their dog ships Everlark. Even I did, on first read. But there are certain gendered nuances that go along with this dynamic. Girls get mocked for pining over unrequited crushes for too long, then get told they should appreciate a boy’s attention even if it’s unwanted. Boys are encouraged to freely pick the girl they want, then get sympathy if they are friendzoned. And then grown men stalk and kill women who don’t want them. Gale and Peeta acting this way is merely annoying, but it’s indicative of a larger problem. Their behavior is normal, so including it in the story wasn’t a bad thing. Not addressing it was the mistake.

By not addressing it, I mean that Katniss feels guilt for hurting these boys’ feelings even when she has been doing her best to keep both of them alive and happy (they’re the ungrateful ones, not her) and no one counteracts it. There’s no moderating influence telling Katniss this isn’t her problem. I get not wanting to sound preachy or heavy-handed, but I can’t even believe that Collins wanted us to critique this ourselves given that Katniss ends up with Peeta in the end. Also, the closest thing Katniss has to such a moderating influence only makes the problem worse.

Haymitch Abernathy, the ‘grouchy but loveable’ mentor of the story, is a drunken middle-aged lout who loves to tell Katniss how much she doesn’t deserve Peeta. He makes Peeta out to be this paragon of virtue and Katniss as a terrible person who is too stupid and ungrateful to appreciate his affection. What is perhaps most bothersome about it is that Haymitch has very little regard for Katniss’s agency.

This is a theme across the books, but it shows up a lot in regards to Peeta. More than just about anything, Katniss can’t stand being stripped of her power to choose. So much so that she decides she would rather die than marry Peeta if she is forced into it. But rather than commiserating about how Katniss’s life is no longer her own, Haymitch tells her she could do a lot worse. It suits his personality, but I can’t help believing he’d have more sympathy for a boy in the same situation. Women should be grateful just to have a good man in their lives, right? A boy’s future being taken away, meanwhile, is tragic (see: just about any white male campus rapist).

It’s debatable how justified Haymitch is in hiding plans from Katniss, both regarding the escape to District 13 and Peeta’s public confession of love prior to their first Games. Both times she is understandably angry with him, and both times he suggests she doesn’t know what’s good for her and it was better for her to know nothing. However true it may or may not be, the way Haymitch talks to Katniss is infantilizing and rightfully makes her more angry. To be fair, Haymitch also hides things from Peeta at times. But when Peeta lashes out over it in Catching Fire, Haymitch tries to placate him by complimenting him and promising he will now be in the loop. He validates Peeta’s anger instead of mocking him for it. What a concept.

Haymitch claiming Katniss doesn’t know what’s best for herself is an issue, especially when paired with his exaltation of Peeta and disparagement of Katniss and her wishes. Unfortunately, in the books Haymitch is mostly portrayed as being right. His is meant to be the voice of realism and reason underneath a facade of cynicism and apathy. This is what I mean when I say THG (inadvertently, I’m sure) reinforced male entitlement in our society. There are many, many Haymitchs out there. Middle-aged mansplainers who know what young women should want and be grateful for, especially when it comes to love. Having a character like this is not a problem in itself—in fact, it’s an opportunity to critique this attitude. The problem is that it never really is critiqued. In fact, once Katniss’s initial anger passes she starts feeling bad for questioning Haymitch’s wisdom and leaves it at that. Yikes.

This comes back to the influential supporting cast being male. Why couldn’t the mentor have been a woman who tells Katniss she doesn’t owe these boys anything? Or tells Peeta to get over himself and accept that Katniss saved his life and, if anything, he owes her? (The situation is complicated by Peeta having arguably saved Katniss’s life when they were kids, but Haymitch doesn’t know that, at least not early on.)

Honestly, I probably would have liked a female Haymitch a lot more. It would have subverted the grouchy mentor trope a bit, of course, as they are typically men. But also, while Katniss and Haymitch already have much in common, a female Haymitch would have understood Katniss a bit better by understanding the way women are socialized and how it affects our behavior. Johanna is sort of like a female Haymitch and I love her, so there you go. At least she belittles Katniss and Peeta equally.

The Verdict

I’m not saying these books are bad. They are very, very good. But they have their shortcomings, and ignoring those while praising them for being ‘so feminist’ in their outlook is counterproductive. As Elizabeth said in our recent podcast, “We’re capable of critiquing things we like.” In fact, being able to do so is important. Taking extreme stances on pieces of media blinds us to not only their shortcomings but their redeeming qualities.

Shortcomings aside, THG is an important story, a story of war and loss and mental illness. And despite all I’ve said, it is still a series with some great feminist qualities and messages. But we should always be looking to improve. We should aspire to do even better, and the way we discuss this series should reflect that.