I don’t know about you, dear reader, but I like the nineties. It’s not merely the wanking weeping thought of being younger. The nineties, in my eyes, were splattered with colour, dynamism and a sense of utter novelty.

Everywhere I walked, my kiddie-pace was anointed with 2Pac, Ace of Base and Dr. Alban. Blasting on my shiny Walkman cassette player; still to this day, on an MP3 player also called Walkman. You could call me a thrall to nostalgia, but I suppose we all have our moments. Likewise, we all got to grow and see this landscape changing before our eyes.

Hindsight made this transformation into an embarrassing experience. Even if endearing in varying grades on the irony scale, it was much the same as adolescence. It was mortifying, clumsy and filled to the gills with ironically-remembered extreme edginess. It was an active renegade-like movement towards the alternative. This was for true for music, and equally so for the comic industry. Today, we’ll look at that company that began as a wrathful shriek against its elders. Much like us, it underwent its own transformation to finally achieve its very own Image.

The Schism

I’m pretty big on Modernism. Yeats, Eliot, Auden—that’s my shit. These poets had to wrestle their own discourse from past conventions in literature. New metric forms, deconstructive motifs and imagery, and a political dimension to a bleak world outlook; these were their means to walk away from Petrarch, Wordsworth, and the like. This is a dynamic reprised time and time again throughout art forms. The comic book equivalent was an exodus of artists trying to escape the shadow of Marvel. But there is more to it than that.

Let’s start basic. In an artistic medium, every artist should be able to claim ownership to their individual work. Fundamentally this is pretty much a given. However, as per the inevitably corporate viewpoint from a company such as Marvel, the collective interest ends up trumping the individual in favour of maintaining stability. This is understood since we’re talking about tradition and cultural foundations. Alas, the work and interests of the individual can be hindered or recompensed below their worth. Such was the case for a group of artists working for Marvel in the early nineties.

After their demands were not met by the company, the bunch left Marvel. However, they didn’t leave for greener pastures, but for a patch of land of their own. This is popularly known as the “X-odus”, given these artists’ involvement with the X-Men comic series. I’m sure one can also attribute a dose of nineties’ extreme-edginess aesthetics.

Pictured above are the leaders of this departure from Marvel. They weren’t merely journeymen or mercenaries, but the ones responsible for revitalizing icons of the comic book industry. Todd McFarlane, Whilce Portacio, Erik Larsen, Jim Lee, Marc Silvestri, Jim Valentino, Chris Claremont, and the infamous Rob Liefeld were virtually celebrities, and their farewell to Marvel caused a reaction in the industry. Together they founded Image Comics, a company centered around one simple notion: the creators own their work. Without the slightest bit of irony, I can say this already sounds swell.

This policy allowed a greater liberty to push the envelope in the accustomed comic book tropes. Subjects unheard of until then could now be explored, at the creator’s desire. The subversive touch to comics during the late forties was revitalized with a vengeance. As a foil to Marvel and DC’s heroes, we got Spawn, Youngblood, The Savage Dragon, etc. These titles were at first published by Malibu Comics while Image was still taking baby steps. Upon becoming a self-sufficient entity, Image left Malibu and took off. Economical stability and the ethos of the publisher allowed for other independent creators to publish through Image while retaining ownership.

Eventually, they became the third largest publisher in the US. The enterprise had become an empire, and the mavericks became filthy-rich stars. Cue the cash register sound effect, for there were toys galore. Cue the rain falling, for the gates to lavishness were now wide open. Now, I don’t know if these fellows did indulge, but it amuses me to think so. Anyway, the notions of independence, diversification and subversion championed this departure to success. Nonetheless, the twilight looms at the end of each day. It was no different for Image. They too suffered a brief schism of their own. I’ll blame Liefeld for it.

I don’t actually bear the fellow any animosity. I’ve no reason to… look at this… (UPDATE: I do hate him now).

An Aesthetic after a Perennial Adolescence

As mentioned above, Image Comics was afforded new liberty in terms of tropes and style. Without the loom of Marvel, possibilities were endless. Nonetheless, much like kids take after their parents, this publisher took after its predecessor. After the splintering off Marvel, Image landed itself on a comfort zone of sorts: the superhero genre. It was still the hegemony of grandiose characters on an action-packed enterprise to defeat evil. However, these new characters appeared to champion a very different direction than the mainstream heroes.

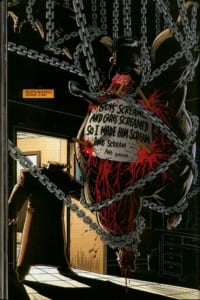

For an impervious Superman, we got a hellishly empowered Spawn. For the mighty Avengers (or Teen Titans), we got Youngblood. A slight resemblance between both paradigms is inevitable, as are the stark differences. Judging by Image’s selection of titles during the early nineties, we can see a dominating aesthetic preference: edgy and bloody. We can’t overlook how art forms are prone to imitate and brandish the tropes of its era. Westerns and Christopher Reeves’ Superman were long gone. In their stead, the blockbuster heroes dominated this decade, guns blazing and catchphrases uttering. It was a paradigm of a more permanent brand of justice.

Likewise, one could argue that the violent approach was a jab at the mainstream’s icons. We can consider the comeuppance delivered unto the villain in Spawn #5 as a beginning to the ultimate departure. Gone was the “indecisiveness” of past heroes. Gone also would be the cult to the ideal in favour of execution and delivery. As this choice progressed into the years, this ‘ethos’ evolved. It became emblazoned with darkness, product of the late nineties’ aesthetics. This is something the young fella of the time could feel identified with, presumably. Bloody, dark, cool… and to be frank, pretty dorky. Looking back, they feel like too forced an attempt to appear more mature than Marvel or DC.

An analogy would be Batman vs. Superman in relation to the Marvel movies. The brooding Superman, the expendable Jimmy Olsen and the pervading blue tint are a clear statement. This superhero movie is not like family-friendly Marvel. We’re not afraid to kill off a beloved character (though we kinda are). Reception about BvS varies, but the intent and delivery of the film seem more of a misguided attempt to appear more serious than Disney-produced Marvel. Likewise, the rad, gritty style of mid-nineties’ Image seems like a hollow threat to its parents. With the power of hindsight, we see these stories brim with adolescence. Gratuitous violence, sex and pouches do not necessarily constitute maturity. However, they might be a stepping stone to it.

Despite this dorky age, Image didn’t entirely lack maturity or inventiveness. The cooperation with other independent artists gave us jewels like The Maxx and Astro City, concepts that subvert themselves while toying with style. At this point, I do believe we can consider these publications as a lovely foreshadowing. The first steps out of the shroud and into a more ambitious kind of subversion. This would be emancipation no different than the young adult moving out of their parents’. Starting 2009, Image began representing true independence and met acclaim for it.

Coming Out the Other Side

Given the circumstances mentioned above, you could say Image fell into a comfort zone of sorts. Eventually, the leading character of Spawn became a god-like entity in-universe. He bested his foes and unmade the universe, and then remade it. And at the end, he passed the torch to another to take on the dark mantle. One could say the aesthetics of edgy, bloody darkness were doomed to repeat themselves over. The palette that saw Image breaking out of the box seemed to grow stagnant. However, the core politics of this publisher would be its saving grace.

Diversification saw the credibility of Image soaring high beyond the tumultuous 2000’s. Some original titles such as Spawn and Savage Dragon are still being published. However, more alternative series have taken the spotlight. However, what indeed do I mean by ‘alternative’? Is it the generic brand used to classify all that doesn’t fit the mainstream back in the nineties? Well, yeah—but not in the same way it was used back then. These alternative genre comics do indeed stand out by foregoing the mainstream superhero narrative. Yet, the palette of colours, themes, motifs and narrative modes is more diverse now.

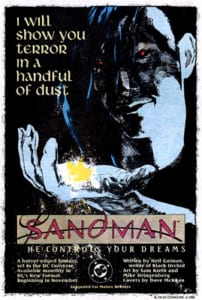

As a personal hypothesis, I’ll attribute this to Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman. Despite DC’s reputation as one of these mainstream elders, this comic book broke the mold way before Image Comics’ birth. Gaiman’s revival of the character created by Jack Kirby and Joe Simon deviated from the conventional superhero narrative. Instead it generated an epic narrative out of storytelling itself, which is one of Gaiman’s signature motifs.

First published in 1989, with a run lasting up to 1996, The Sandman paved a way to endless narrative possibilities. Collaborations with the likes of Sam Kieth and Alan Moore also shaped a most peculiar aesthetic. Darkness without a necessity to establish itself as so; organic, natural, and I dare say, inevitable. You bet your beautiful asses we’ll talk about The Sandman in here eventually.

Nonetheless, this beauty may have influenced a generation through its style and diversity. While Image howled its bloody primal scream, these sowed ideas germinated in enamored brains. I’d wager that then-future creators became inspired by such an ambitious work. The Sandman was demonstrated that virtually anything could become a story, it eventually happened, as new creators became affiliated with Image. So, this generation who likely read The Sandman reveled in the liberty to make comics about anything and everything.

Furthermore, the leap from the nineties to the new millennium in terms of ideas is also a factor. It’s not merely that dark and edgy anti-hero stories saw their twilight. It’s also the fact that the entire world had changed. New worldviews became relevant, and ideological barriers came down. Social conscience and messages found their way back into the narrative art. This genesis of independent creators echoed with a sense of urgency, delicious yet serious. In my humble opinion, timing was everything.

An Image of Our Own

Sometimes they outrageously defy our expectations. Sometimes they migrate the battlefield into uncanny unlikely places. Sometimes they retell a classic under new rules. Sometimes it’s just pure mindless colourful fun. This endless amount of narrative possibilities has changed the focus for Image Comics. And the ultimate confirmation of this is the shift in competition. There’s no longer a need to stick it to the elders; to DC and Marvel. The founders made their point long ago: creators get to own their own work. Matter solved, the publisher gets to truly be its own thing: an enterprise for the independent. Nowadays, its’ competition is Dark Horse Comics, and even perhaps DC’s Vertigo.

When Leo won his Oscar, I blasted Fatboy Slim’s “Praise You” all week. It really was a long way he came to his triumphal moment. One could say the same for Image and its readership. “We’ve come a long, long way together, through the hard times and the good. I have to celebrate you, Image. I have to praise you like I should.” And indeed, let’s praise Image for successfully wading through these growing pains.

Even now, we can fondly look at these edgy dorky issues past with some manner of endearment. Whether by appreciating them in a postmodern sense, or as what they are: idiosyncrasies from a younger, more volatile age. And above all, let’s celebrate what we’ve got now, thanks to this crux of circumstances. In a world stranger than fiction, diversity is key for survival. For each image of reality, there may well be a story.

Now, lovely reader, allow me to finish by turning this into a glorified prelude. Soon, we will be reviewing two of the most acclaimed Image series of the past decade. Double-Feature Fridays: Saga (Vaughan & Staples) and The Wicked + The Divine (Gillen & McKelvie). One is an epic-space opera involving star-crossed lovers and lots of fucking. The other is an uber-English narrative of Gods and Humans I could write a dissertation on; presumably a lot of fucking too. It’s going to be genre-transgressive, engaging, colourful and sexy as fuck. Thank you for reading, and I love you.