Greetings, readers of the Fandomentals. In this iteration of my video game ramblings, I’d like to talk about something rather specific. There are games that are deliberately designed as “old school”, and “spiritual successors” of old games. Pillars of Eternity is one example, calling back to the old Infinity Engine titles. Shadowrun Returns is another. And yet, I think those two games have one huge advantage over the older titles – they don’t try to imitate tabletop rules. Instead, they focus on the experience.

The most notable examples of tabletop rules on a computer screen are Baldur’s Gate, Icewind Dale, and Planescape: Torment. They use the second edition Advanced Dungeons and Dragons rules, with some tweaks here and there.

I have a special place in my heart for those games – or, rather, Baldur’s Gate and Planescape: Torment. I’ve tried to get into Icewind Dale several times, but it was futile. It’s little more than a series of difficult combat encounters in an unenjoyable system. Which plays into what I’m talking about below.

I have a special place in my heart for those games – or, rather, Baldur’s Gate and Planescape: Torment. I’ve tried to get into Icewind Dale several times, but it was futile. It’s little more than a series of difficult combat encounters in an unenjoyable system. Which plays into what I’m talking about below.

I’ve already written about why Planescape: Torment’s story is very poorly served by its rules. Baldur’s Gate, on the other hand, is very much the kind of story that AD&D portrays. A band of heroes (or roaming murders and robbers, if you’re evil) fighting monsters and villains, delving into dangerous places, recovering copious amounts of loot… it’s all there.

And yet, I’ve come to the conclusion that the rules the game uses don’t really contribute to that. They don’t get in the way to such a degree that you can’t enjoy the game – that is, I enjoyed it. Many others didn’t, and it’s a matter of taste. Regardless, I think the game’s popularity is despite the ruleset, not because of it. Being clear, my opinion about the AD&D 2e rules is very, very low. I’ll do my best to keep my bias out of this article, however.

The root cause of why tabletop rules don’t translate well to a computer game is the social aspect. A tabletop game, regardless of its genre, style and rules density, is a social activity. In most cases, there’s one person running it (the Game Master, Dungeon Master, Storyteller or even Seneschal, if you’re Riddle of Steel and thus pretentious). The GM is there to serve as an interface with the rules and the players. Even in very detailed and dense rules, it’s acknowledged that they can’t account for everything.

Not so much in a computer game, where everything that happens has to be programmed and scripted. So there’s very little leeway in how the game applies its rules. So when you apply a tabletop ruleset to it, a lot of its elements will simply disappear. Particularly so in a system like AD&D, where a lot of things operate on a basis of winging it as necessary.

The part of the game that suffers the most for it is the non-combat rules. Computer-based RPGs tend to focus on fighting much more than tabletop ones do (even D&D, where combat is a major focus). The reason is that social or mental challenges require a different approach, and much more on-the-spot adjudication by the GM. The good ones, that is – I’m not talking about locks or traps that you just need a high enough number to get past.

Thus, such challenges become a measure of having a particular skill, attribute or something like that. Either you have it, and pass, or you don’t. They’re thus much easier to „solve” than combat – even if a player avoids spoilers and walkthroughs, they will only be difficult once.

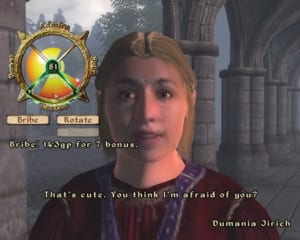

That’s the major breaking point here – combat in video RPGs is a delicate balance of character building an on-the-spot tactical decisions. Non-combat challenges tend to boil down to the former. There have been some attempts to introduce the other layer to them, but without much success, in my experience. The Elder Scrolls 4: Oblivion has a persuasion minigame that tends to result in lowering your disposition with a given NPC. There’s also the lock-picking minigame, that has the problem of making the actual skill matter too little. The Fallout games from Fallout 3 onwards try to solve this problem by requiring a minigame to pick locks, hack computers, et cetera, with the numerical skill determining whether you can even attempt. It doesn’t work half bad.

Of course, the Fallout games, whether in their old incarnations or the first-person ones, have their own rules. Which brings me right back to the central theme of this article.

Baldur’s Gate 2 wasn’t the last computer RPG to use the Dungeons & Dragons ruleset. The Neverwinter Nights series utilizes the 3e ruleset. Temple of Elemental Evil is most famous as a very faithful adaptation of the system, complete with turn-based combat. And a whole bunch of tiny little details that don’t quite work.

The Neverwinter Nights games show clear signs of strain when it comes to adapting the D&D rules, as well. Their combat is real-time, which plays very poorly with D&D’s turn order. D&D is full of abilities you declare before you take an action. Real-time combat makes them difficult.

And, again, there’s the issue of a sharply limited environment. This is particularly applicable to magic – D&D being very reluctant to let non-magical characters do anything remotely interesting.

I talk about D&D games here, because those are the only ones I’m familiar with that directly transplant tabletop rules into a video game. If there are others, I don’t know of them. Vampire: the Masquerade – Bloodlines is a fairly faithful adaptation of the Vampire: the Masquerade rules, but it still makes a lot of allowances. Which is for the best, seeing as those rules make AD&D look good in comparison. If there are others, I’m not familiar with them.

I talk about D&D games here, because those are the only ones I’m familiar with that directly transplant tabletop rules into a video game. If there are others, I don’t know of them. Vampire: the Masquerade – Bloodlines is a fairly faithful adaptation of the Vampire: the Masquerade rules, but it still makes a lot of allowances. Which is for the best, seeing as those rules make AD&D look good in comparison. If there are others, I’m not familiar with them.

Regardless, all of those games have a clear goal – to appeal to the people who already like Dungeons & Dragons. But I think they make the mistake of imitating the form, rather than the experience of playing the game. Which is where Pillars of Eternity and Shadowrun Returns come in.

Pillars of Eternity was billed as a spiritual successor of Baldur’s Gate. Which made it appeal to those who hate everything about the RPG genre afterwards. My sarcasm aside, the callbacks are very obvious, and do tug at a nostalgic player’s heart-strings. But there’s much more to it. After I’ve played it in its entirely twice, and bitten into it, I realized what it is, exactly.

I won’t say that the game doesn’t have its own problems. Many of them stem from adherence to D&D trappings. But it has a far greater clarity of purpose, and tailors its mechanics to being a computer RPG. In doing so, it creates the experience of playing D&D – having a party, having classes that represent particular archetypes, and so on. But it also realizes that you don’t need the exact rules to produce such an experience.

I’ve already talked about things inherent to tabletop games that don’t really work in a computer game. Pillars takes advantage of the opposite – elements that work in a computer game, but not a tabletop one. Take damage reduction, for one. There’s a number of types of damage, and every character or creature will have different defences against them, based on their equipment and traits. This creates a lot of interplay and tactical consideration… but it’d turn a GM’s hair grey if they had to keep track of it all. A computer will make all those calculations in the blink of an eye.

Another thing Pillars does is realize that the impact of your party in conversations is going to be limited, making a charisma attribute or diplomacy skill an illusion of choice. So it makes all attributes and a variety of other factors matter in them. It doesn’t entirely succeed – some are much more useful than others when talking. But the attempt is there.

Now, computer RPGs that don’t use tabletop rules at all aren’t exactly rare. But in this specific case, we have a computer RPG that is very deliberately evoking a certain tabletop game, without using its rules. Thus setting up the contrast between imitation and experience.

My other example is Shadowrun Returns. The game has humble origins, but it improves massively with its two later campaigns, Dragonfall and Hong Kong. The games take place in the universe of Shadowrun, which is a near-future setting after magic returned to our world.

of Shadowrun, which is a near-future setting after magic returned to our world.

The Shadowrun rules that I’ve seen, in their fourth and fifth editions, are a beast of a thing. Dense, detailed and full of moving parts. I can make no statements on how they actually run, since I’ve only read them. Nonetheless, whether or not dense rules are your thing, transposing them into a computer game would be a fool’s errand.

And so the Shadowrun Returns games don’t really try. Instead, it creates an enjoable tactical turn-based game, with relatively simple character creation that enables all the different character archetypes present in Shadowrun.

The important thing that Shadowrun Returns accomplishes is, once again, the exprerience of playing the system. A lot of it has nothing to do with rules, of course – the oppressive and dreary atmosphere of a world choked by corporate greed and pervading selfishness. That’s all about the writing and plotting.

Still, the mechanics are also a layer of immersion into the setting. And I belive Shadowrun Returns succeeds here as well. The mix of technology, magic and brute force is there. So is the need for a diverse group to handle different challenges. It’s also simply tactically engaging and fun.

Both Pillars of Eternity and Shadowrun Returns are deliberate callbacks to an older era of gaming. Some even call them part of an „isometric revival”. I’ve struggled to reconcile my sympathy for them with my distaste for this reactionary sentiment. And I think that the difference between imitating the form, and reliving the experience, is the key here. Games such as Pillars of Eternity and Shadowrun Returns bring us a familiar atmosphere, and remind us of old, beloved games. But they do so with a focus on function over form.