Here at The Fandomentals, we spend a lot of time thinking about adaptations, from the elements that aid in their successes, to the execution that makes them…something else entirely.

I smugly thought that I had it all figured out, thanks to our slightly overzealous analyses of Game of Thrones: it’s all about themes and characterizations. But which is the master and which the apprentice? To that, I had also concluded (with great certainty) that if you have the themes, the characters follow; after all, if the underlying messages or points of a narrative are adapted, how could they exist without the personalities that bring them about in-tact?

Arya in Game of Thrones would seem to be a counter-point. After all, her Season 5 plotline was rather obviously centered around the theme of REVENGE. Readers of A Song of Ice and Fire will agree that this features in her book plotline as well. However, this is where we get into the messiness of parsing out the “central theme.” I would argue, and have, that Arya’s arc in the books is much more focused on identity, with revenge being a component of this; however, in the show, revenge was the end, with no consideration to the means or meaning of why that mattered to her—a difference that Julia and I spend over 7000 words explaining.

Trying to shift the focus from the central theme to a supporting one? That changes the story profoundly, especially since themes are, you know, the reason a story exists. This is why we very much advise against a drinking game every time the word “theme” appears in one of our articles.

So there I was, building an altar to worship that lens of literary analysis, when I remembered one of my least favorite adaptations in existence: Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd from 2007, an attempt to bring Stephen Sondheim’s 1979 musical to screen.

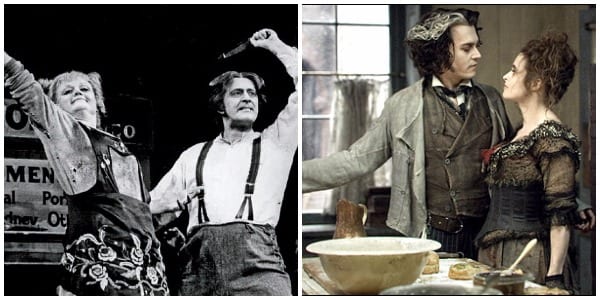

It’s low-hanging fruit to criticize as an adaptation. It’s Tim Burton, the guy who shoehorned Christopher Lee the dentist-dad of Willy Wonka into Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and it stars Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter (because of course it does), both of whom have no business singing a broadway score. Sweeney Todd isn’t exactly Bye Bye Birdie, a musical with a lot of talking where the charisma of an actor can cover this up (though I’ll defend Jason Alexander as Albert); it’s considered an operetta because of its lack of dialogue.

But the thing is…its themes were more or less adapted perfectly. As I said before, it’s not exactly that deep. Sweeney Todd is the tale about the futility of revenge, how an obsession with it leads to self-defeat, and how those caught in the plan suffer. It may or may not also be an allegory for capitalism, but the story of the ‘demon barber of Fleet Street’ himself is quite clear. And of course it was adapted, because that’s also the entire plot, and what every song is centered around. It’s a bit hard to perform “Epiphany” with any other central message.

“And I will get him back even as he gloats, in the meantime, I’ll practice on less honorable throats.”

Yet even ignoring the sophomoric singing and the Burton-stylized blood, this was far from a successful adaptation. And that’s for one reason only: the characters.

I could easily complain about the decision to age Toby down (though thematically it somewhat strengthens the horror aspect of it all), or how Antony and Joanna were barely in the thing (and not at all memorable). But frankly, there’s only two characters that need close attention: Sweeney Todd and Mrs. Lovett. Angela Lansbury is a nearly impossible act to follow for anyone, but what sells her character, and what other actors generally mimic, is her chipper demeanor and vivaciousness. This is especially due to the fact that the role serves as a counterweight to Todd’s quiet and intensifying anger (or in George Hearn’s case, obvious and severe anger from the start). Yet with Depp and Carter, this duo seemed more sedated than anything else. I truly thought they might pass out in the middle of “A Little Priest” from their apparent boredom.

What this did was essentially kill the tone of the play. Despite being a horror-musical, Sweeney Todd also functions as a dark comedy, and it’s really the genre blend that makes the entire show. So when you have two completely blah characters trying to make clever puns about pies, it just becomes more confusing than anything else.

It also made Toby’s affection for Mrs. Lovett infinitely confusing, since she barely gave the poor kid anything back. All we were left with, as the audience, were the very bright-red blood splatters and the memory of a surprisingly solid Pirelli performance by Sacha Baron Cohen. Probably because he was allowed to be funny. But one side-character does not a good adaptation make (see: Viserys Targaryen).

Because of this film, when the 2014 Into the Woods movie was announced, I was instantly apprehensive. I take poor Sondheim adaptations…rather personally.

Yet I left that theater grinning ear to ear, because it was a film that *got* it. And that was due to the characters.

Sure, Meryl Streep provided a wildly different type of witch to Bernadette Peters, but yet her hypocrisy, her black-and-white thinking, her terror of losing her daughter juxtaposed to her indifference over the personal plights of others…it was all there. Then Cinderella was still that indecisive bird-whisperer who grew into a position of responsibility, The Baker’s Wife was that moral[ly ambiguous] heartbeat (I was sure “Moments in the Woods” was going to be on Disney’s chopping block), and the dashing princes were, well…

Heck, even Depp’s role was passable in this one.

At the same time, I’d argue that a lot of the themes present in the stage version were, if not neutered completely, severely toned down.

The perversion of wish fulfillment and collective responsibility are the two main takeaways of this musical. The latter is present, mostly thanks to the songs “Your Fault” and “No One is Alone” being adapted in full. Again, the lyrics do the job for them:

“People make mistakes. Fathers, mothers, people make mistakes. Holding to their own, thinking they’re alone.”

As Sondheim explains:

“I have read criticisms and heard criticisms of the idea of this song by people who say ‘it’s nonsense, we’re all alone.’ There’s a famous line…I think it was Thomas Wolfe… ‘We are all strangers and alone’ [sic]. But the point is, that’s not the kind of ‘alone’ that this song is about. It means that we all need and depend on each other. And of course we are all, in a sense, profoundly alone, but not when we are connected with each other.” —Stephen Sondheim, “MTI Conversation Piece with Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine”

The “kind of alone” he’s talking about was made obvious when they all have to take down the giant simply because it’s the right thing to do, and how they all, by necessity, must have a hand in doing it.

However, the perversion of wish fulfillment is at the least equally important, and brought into sharp focus within the same song that demolishes the idea of blame for a situation (“Last Midnight”). In other words, the thing that was keeping them from fulfilling that community-focused theme until the very end.

“Had to get your prince, had to get your cow. Had to get your wish, doesn’t matter how. Anyway, it doesn’t matter now”

You can’t separate one theme from the other, and the former is so hammered on that the first act closes to “Ever After,” where the entire cast sings about the joys of their dreams coming true, only for the rug to be yanked out from under them during the remainder. On film, this song was scrapped.

The movie kept in the witch losing Rapunzel in her life, yet in the stage production, Rapunzel dies, amplifying this point and allowing for the witch’s decent to make a lot more sense. There’s supposed to be a reprise of “Agony” where the self-involved princes sing with the same passion about two completely different princesses, which didn’t make it to the screen. For a story that was supposed to flip “anything your heart desires will come to you” on its head, we got an adaptation that didn’t even seem to realize that was a subversion that was supposed to happen.

Even the secondary theme of “everything is bad because of parents” was toned-down, especially given how decreased the role of Jack’s dad was.

Yet it felt right, and it felt right because of character interplay. As a result, the tone was captured perfectly. I wasn’t leaving the theater thinking about how the absence of “Maybe They’re Magic” hampered the darker turn of the second act…I was thinking about Anna Kendrick’s face she made at the Baker’s Wife when she was told that the woman needed her shoes to have a baby.

This is not to say themes are unimportant: the best adaptations certainly focus on the central ones from the original source. But the best stories are those that are character-driven. For that reason, an adaptation can present the intended message of the author perfectly, yet if its characters don’t feel right, that message will be undercut.