“The Great River” is the first chapter in Book II of The Fellowship of the Ring that feels a bit redundant. In terms of emotion, we’re in the same spot as “Farewell to Lórien.” Despite definite forward progress down the river, all of our characters are still trapped in indecision, unsure whether to head east or west.

In terms of setting, the chapter feels like a callback to “The Ring Goes South.” There are a lot of dreary barren landscapes, ominous circling birds, and hints of paranoia (and both after a nice reprieve at an Elven stronghold). It’s a treading water chapter, despite the fact that it is very literally the opposite of that (sorry). But even though the narrative stagnates, there are plenty of nice little details in “The Great River,” and it provides a perfect opportunity to talk a bit about Tolkien’s use of language and landscape.

Landscape and Prose

Tolkien’s prose has gotten a lot of side-eyes over the years, from parties no less illustrious than the Nobel committee. This is somewhat baffling to me: I’ve always viewed it as one of Tolkien’s greatest strengths. It’s weird prose, absolutely. You can call it archaic and out-of-fashion. And a quick Google search tells me that’s how most of the discussions break down—one person claims Tolkien has bad prose, another counters that he just has old prose. I’d argue that he doesn’t really have either.

Now, of course Tolkien has old-fashioned prose. He was a medievalist who worked for the Oxford English Dictionary. He cribbed from medieval romances, he stole etymologies from a whole host of languages. Dude was a NERD. In that light it’s easy to see his work as medievalist fan fiction or a linguist getting a little overly involved with his work.

That is true, but seeing Tolkien only in that light does him a disservice. Tolkien borrowed from medieval language and literary forms, but he transformed it into something else: that’s what literary innovation is. When anyone reads medieval Germanic poetry they’ll see the inspiration, but no one is going to think they’re reading Tolkien.

There are similarities, of course. Take a look at “The Seafarer,” an early medieval Anglo-Saxon poem.

The days are dwindling now

of the kingdoms of this earth;

there are no kings or Caesars

as before, and no gold-givers

as once, when men of valor

performed great deeds and lived

majestically among

themselves in high renown.

Their delights too are dead.

The weakest hold the world in their hands

And wear it out.

This is super Tolkien-y, in both prose and theme. There’s the sense of lost grandeur, of kingdoms and times irrevocably gone, to the detriment of the present. There’s the almost compulsive need to stuff as much alliteration in as possible. With only the slightest emendation, this could stand in for Theoden’s speech in “The King of the Golden Hall” in The Two Towers.

Where now is the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing?

Where is the helm and hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?

Where is the hand on the harpstring, and the red fire glowing?

Where is the spring and the harvest and the tall corn growing? ‘

They have passed like rain on the mountain, like a wind in the meadow;

The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow.

It’s also very reminiscent of Tolkien’s prose when the Company coming upon old ruins in “Fog on the Barrow Downs” or “Flight to the Ford.”

But Tolkien also makes this sort of literature his own, and turns it into something new. He does this linguistically as well, to fascinating effect—please go read this wonderful article if you have any interest in linguistics. But let’s take a look at how Tolkien does it with landscape (something he writes about A LOT). And let’s compare it to Beowulf, everyone’s favorite Tolkien reference point.

A few miles from here

a frost-stiffened wood waits and keeps watch

above a mere; the overhanging bank

is a maze of tree-roots mirrored in its surface.

At night there, something uncanny happens:

the water burns. And the mere bottom

has never been sounded by the sons of men.

On its bank the heather-stepper halts:

the hart in flight from pursuing hounds

will turn and face them with firm-set horns

and die in the wood rather than dive

beneath its surface. That is no good place.

When wind blows up and stormy weather

makes clouds scud and the skies weep,

out of its depths a dirty surge

is pitched towards the heavens.

Yikes! This is a description of the bog where Grendel’s mother spends her days. It’s certainly reminiscent of Tolkien. The alliteration is there and phrases like “a maze of tree-roots mirrored in its surface” or “when the wind blows up the stormy weather / makes clouds scud and the skies weep” sound like could be plucked verbatim from a page in The Fellowship of the Ring. But let’s take a step back and look at the purpose of this passage. This is the description given to Beowulf before he heads off to battle. It sets the tone for the scene, an ominous, fearful bog that’s light years away from the cozy Heorot Hall (you know, pre-monster attack). Landscape here manifests an external challenge. The landscape is scary because Beowulf needs something to fight, and the stakes have to be high enough for it to matter.

Tolkien does this as well.

“The Brown Lands rose into bleak wolds, over which flowed a chill air from the East. On the other side the meads had become rolling downs of withered grass amidst a land of fen and tussock. Frodo shivered, thinking of the lawns and fountains, the clear sun and gentle rains of Lothlórien. There was little speech and no laughter in any of the boats.

“There were many birds about the cliffs and the rock-chimneys, and all day high in the air flocks of birds had been circling, black against the pale sky.”

This is just landscape as an external threat and it’s a very common trope in pre-modern literature. But Tolkien’s use of landscape also does something different. Here’s another depiction of the Company’s trip down the Anduin:

“On this side of the River they passed forests of great reeds, so tall that they shut out all view to the west, as the little boats went rustling by along their fluttering borders. Their dark withered plumes bent and tossed in the light cold airs, hissing softly and sadly. Here and there through openings Frodo could catch sudden glimpses of rolling meads and far beyond them hills in the sunset, and away on the edge of sight a dark line, where marched the southernmost ranks of the Misty Mountains.”

The key difference here is that this is not simply a description of a landscape. It’s a description of Frodo observing a landscape. It’s a key difference, and one that reorients the entire purpose of a description of landscape in a piece of literature. Landscape in Tolkien rarely exists simply as a challenge or an obstacle to overcome (though it obviously can be that). Instead, it functions as a mirror for the interior lives of characters.

Frodo and Landscape

I counted three time that Frodo explicitly observes the world around him in “The Great River.” Each time he observes the landscape (rather than the landscape simply being described), it happens in a very particular fashion. The first was above, when he observes the forests of reeds, “hissing softly and sadly” that suddenly open up to reveal “rolling meads, and far beyond them hills in the sunset.”

The other occurs when Frodo looks up as Legolas as he bends his bow to shoot at the orcs across the river:

“Frodo looked up at the Elf standing tall above him, as he gazed into the night, seeking a mark to shoot at. His head was dark, crowned with sharp white stars that glittered in the black pools of the sky behind. But now rising and sailing up from the South the great clouds advanced, sending out dark outriders into the starry fields. A sudden dread fell on the Company.”

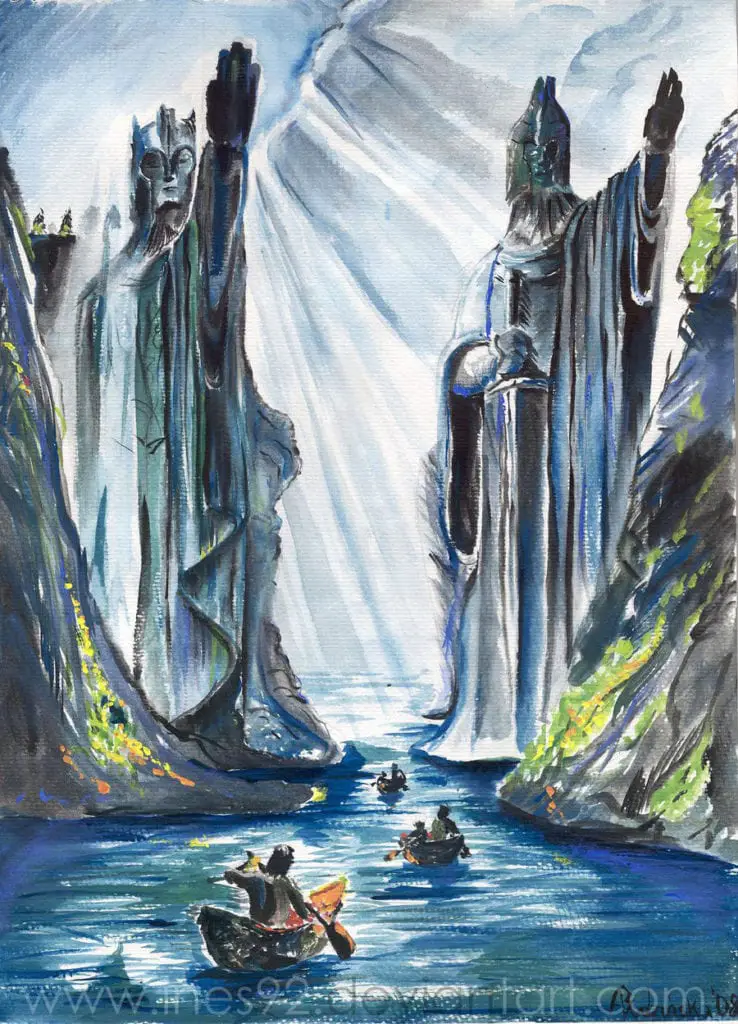

And the last is when the Company passes through the channel between the Argonath:

“As Frodo was borne towards them the great pillars rose like towers to meet him. Giants they seemed to him, vast grey figures silent but threatening. Then he saw that they were indeed shaped and fashioned: the craft and power of old had wrought upon them, and still they preserved through suns and rains of forgotten years the mighty likenesses in which they had been hewn. Upon great pedestals founded in the deep waters stood two great kings of stone: still with blurred eyes and crannied brows they frowned upon the North… the boats whirled by, frail and fleeting as little leaves.”

On all three occasions, Frodo (1) sees one thing that then transforms into something else and (2) envisions himself as small in passive in the face of the massive forces that surround him. This is underlined, of course, by the fact that Frodo spends the majority of the chapter sitting passively in a boat and floating south through no effort of his own. He first views the battle with the orcs as a battle between the stars surrounding Legolas’s head and the shadow that threatens to eclipse them. He views the Argonath as immortal and immoveable sentinels, as their boat flit by beneath, “frail and fleeting as little leaves.”

Frodo is a reticent protagonist. He doesn’t often spill out his feelings onto the page. But his feelings can be grasped by watching how he reads the landscape around him. He feels powerless in this chapter, and his readings of the landscape are Tolkien’s way of articulating that. As far as I know that is substantially different from the medieval romances and Anglo-Saxon poetry from which Tolkien obtained his inspiration and allots more psychological depth to Tolkien’s characters. Landscapes have a multitude of meanings in Tolkien’s prose and they serve to illuminate how he borrowed from premodern literature but also turned it into his own.

Final Comments

- All of this is true of Aragorn as well, of course. But his is more explicit. The river is both a reprieve from his decision and the power bringing that decision increasingly closer. It’s one of the starker scenic departures in Peter Jackson’s movie. There, the trip down the Anduin is fraught and fast, as the Fellowship’s paddling is intercut with shots of incoming Uruk-Hai. Much of the trip occurs between two cliff faces, giving the sense that the Fellowship knowns exactly where it’s going and is aiming to get there as quickly as possible. That’s in stark contrast to the book, where the trip is characterized by open space (all the better to echo the Company’s indecision).

- I like how the Argonath inject some life into the otherwise wishy-washing Aragorn. But in the end it’s probably just making his decision harder. He obviously wants to go to Minas Tirith, and feels that to be his destiny. But the idea of just ditching Frodo at this point seems really awful.

- Poor Boromir is having a hard time this chapter. While Frodo doesn’t where his heart on his sleeve, Boromir wears it on both sleeves and occasionally shoves it in people’s faces. His temptation by the Ring makes him repeatedly grab a paddle and frantically row up close to Aragorn’s boat (which is sad, but also a little funny?) And he also provides us with this true work of passive-aggressive art. “It is not the way of the Men of Minas Tirith to desert their friends at need,” he said, “and you will need my strength, if you ever reach the Tindrock. To the Tall Isle I will go, but no further. There I shall turn to my home, alone if my help has not earned the reward of any companionship.” CHILL, BOROMIR.

- Gollum has been following the Company for a while now, and at least Sam, Frodo, and Aragorn have noticed. They win the award for most observant boat. I’m a little surprised a Ranger of Aragorn’s ability hasn’t been able to catch him.

- I’m going to start using “That is no good place” from Beowulf in my daily life. It’s such a great understatement. The water bursts into flames and rabbits commit suicide rather than jump in. No good place, buddy!

- On a side note: it’s hard to argue over whether prose is “good” or “bad.” I mean, if you hate semicolons, passive voice, and long sentences, Tolkien is going to be a rough read for you. A lot of people think Hemingway’s prose is genius, but blech. I’m not sure I’d argue that it’s entirely subjective, but I also don’t know what the objection criteria for judging it would be.

- Prose Prize: “The air grew warm and very still under the great moist clouds that had floated up from the South and the distant seas. The rushing of the River over the rocks of the rapids seemed to grow louder and closer. The twigs of the trees above them began to drip. When the day came the mood of the world about them had become soft and sad. Slowly the dawn grew to a pale light, diffused and shadowless.”

- Happy Thanksgiving! We’ll finish up The Fellowship of the Ring in the beginning of December.