“The Last Debate” is more like a “last discussion,” a “last planning meeting,” or perhaps a “last Gandalf monologue with which everyone is quickly on board.” This isn’t a criticism. A debate at this point would feel out of place. Our heroes have just been granted a miracle, an impossible reprieve. But what can you do next? What to do when you’ve been given a miracle, you’ve survived, but you simply immediately require a bigger one?

The whole chapter is tinged with a sense of giddiness, fear, hope, and confusion. People like Legolas look to a future beyond the war, but one that is different, uncertain, even frightening. Cut off from what had come before. Éomer’s eucatastrophe is built on the back of Gimli’s week of horror, a time he came barely bring himself to recall. And when the captains gather together to plan a course for what’s to come, they quickly agree that the most hopeful path is virtually indistinguishable from self-annihilation.

The Last Debate

“Hardly has our strength sufficed to beat off the first great assault,” Gandalf begins at the meeting of the captains. “The next will be greater.” It might come across as a narratively jarring moment for those uninitiated to Tolkien’s pacing. We’ve shifted quickly from a moment of narrative and emotional climax to one where… our heroes aren’t even entirely the protagonists anymore. Of course, they still are in a certain sense. But it’s still an interesting and rather bold move on Tolkien’s part to follow up such a vibrant, effective set piece as Pelennor Fields with its stars scrambling to fill a supporting role to quieter characters who have been off screen for so long.

From a thematic point of view, of course, this is essential. Tolkien’s physical battles, as important as they may be, are always secondary, always a corollary to something more key. We saw this last chapter when Aragorn gained renown in Minas Tirith for his healing powers rather than his ghost brigade, which he didn’t even both to bring. It would make little sense to have this strand of narrative culminate in a big battle before shifting over to Frodo and Sam, implying an equivalence in their missions despite the fact that they are playing dramatically different roles.

It’s also thematically on point in its skewering of Sauron’s lack of imagination. Sauron has always struck me as the sort to be quite proud of himself for being able to see the weaknesses in others. He probably thinks he’s a goddamn scholar of the human (elven/dwarven/you get it) condition because of his ability to see how others could fail. How intelligent! How edgy. Of course, Sauron’s certainty in himself is his own undoing (Aragorn’s certainty, hard-earned and open-minded, sounds nicely as its counterpoint). Non-Saurons are simply Lesser-Saurons: they would hide without the Ring or fight rashly with It. Playing into this isn’t quite prudence, as Gandalf notes. But it’s a solid play predicated on Sauron’s weakness and their own tentative, tottering strength.

Seen and Unseen

Now that we’ve gotten our spaghetti plate of plot threads all (relatively) back together, I’d be curious to see what everyone thinks about Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli’s adventure happening almost entirely off screen. Much like the Ents’ assault on Isengard, I do think that it loses a bit from being told in retrospect.

We hear Legolas and Gimli describe the moments they saw Aragorn really come into his own as an open leader of large numbers of people (and ghosts) rather than see it happen ourselves. We don’t see Legolas and Gimli for a very long time! And, from what snippets Tolkien does give us, we missed some very cool and atmospheric ghostiness. I was especially a fan of Gimli, ever the wordsmith, describing the army right before Aragorn released them. “The Shadow Host withdrew to the shore. There they stood silent, hardly to be seen, save for a red gleam in their eyes that caught the glare of the ships that were burning.”

But in the end I think it was a good choice to keep the focus away from Aragorn, and instead give us Eomer’s moment on the Pelennor. It’s a more thematically important moment than the taking of the fleet at Pelagir, despite the cool, ghostly atmosphere of the latter. I do sometimes wonder, though, at what story would have emerged had the choice been reversed.

Legolas, Gimli, and Future Might-Have-Beens

While there’s good stuff all over, I do have to say that my favorite part of the chapter, by a long shot, is simply Merry, Pippin, Legolas, and Gimli hanging out by the Houses of Healing. They’re among the funniest characters in The Lord of the Rings and they are very well-paired here. Merry and Pippin so often bring out the best and most honest in others, and the tension between Legolas’s and Gimli’s wildly disparate approaches to the world creates a nice sense of dynamism and tension. Tolkien delightfully plays it up almost to the point of parody as they enter Minas Tirith: “Legolas was fair of face beyond the measure of Men, and he sang an elven-song in a clear voice as he walked in the morning; but Gimli stalked beside him, stroking his beard and staring about him.”

Beyond that, though, their conversation also strikes a tenor that new in this section of The Lord of the Rings. Legolas and Gimli immediately begin discussing how, after the war, they could call on some good dwarven stonewrights to fix up shoddy Minas Tirith masonry and some trusty elves to plant some flowers and make the place less drab and lifeless. There’s a sense of hope, of the future, of time expanding outward and the world improving from what it currently is. But there’s also the sense of that hope being suddenly and somewhat truncated.

“It is ever so with the things that Men begin: there is a frost in the Spring, or a blight in Summer, and they fail of their promise.”

“Yet seldom do they fail of their seed,” said Legolas. “And that will lie in the dust and rot to spring up again in times and places unlooked-for. The deeds of Men will outlast us, Gimli.”

“And yet come to naught in the end but might-have-beens, I guess,” said the Dwarf.

“To that the Elves know not the answer,” said Legolas.

It’s clever that the first look at the future, of a post-Sauron world, comes from an elf, a dwarf, and two hobbits sitting around the citadel of Men that is likely to be the focal point of the future. It’s such an ambiguous future: obviously better than the immediate present, but still heavy with the sense of loss. The world will be Different. That’s very sad in a lot of ways, and a lot of people over the rest of the story are gonna be sad about it. But it’s not—or not necessarily—bad. This becomes even clearer when Legolas sees some seagulls, the Middle-earth brand of wildlife doomed to launch mid-life-crises for elves whose lives have no mid.

“Look!” he cried. “Gulls! They are flying far inland. A wonder they are to me and a trouble in my heart. Never in all my life had I met them, until we came to Pelagir, and there I heard them crying in the air as we rode to the battle of the ships. Then I stood still, forgetting war in Middle-earth; for their wailing voices spoke to me of the Sea. The Sea! Alas! I have not yet beheld it. But deep in the hearts of all my kindred lies the sea-longing, which it is perilous to stir. Alas! for the gulls. No peace shall I have again under beech or under elm.”

I’ve always liked that Tolkien’s “dying world” (hmm) atmosphere is predicated not on death but on movement. The elves aren’t… disappearing, or dying, or Losing Their Magic. They are simply going somewhere else, to a new place. That is super sad in a lot of ways! I am a historian and I cry into my tea every morning that I can’t chill with medieval scholars in Timbuktu or scratch crass graffiti into Pompeiian walls with Roman bros or learn to paint pretty landscapes in Song China. Gimli gets it.

“Say not so!” said Gimli. “There are countless things still to see in Middle-earth, and great works to do. But if all the fair folk take to the Havens, it would be a duller world for those who are doomed to stay.”

But it’s not necessarily a bad thing. Tolkien’s world is not a world of consistent linear decline. Things don’t start beautiful and get bad. I mean—they get bad a lot if you read The Silmarillion, but it is very hard to be kind in a world with so much beautiful jewelry up for grabs. But in the large scheme of things, for Tolkien, change is sad but fundamentally neutral: as in all things, it depends on the choices that you make. There’s ample space made for sadness and loss, but at its core I think it’s a rather optimistic way to view the world.

In any case, more on this later. I am very interested in Tolkien’s sense of nostalgia. But I think I’m going to save any more thoughts for a later chapter (or just a later essay in general). It’s more complicated and optimistic than it’s often painted to be, at any rate.

Final Comments

- “Other evils there are that may come; for Sauron is himself but a servant or emissary. Yet it is not our part to master all the tides of the world, but to do what is in us for the succor of those years wherein we are set, uprooting the evil in the fields that we know, so that those who live after may have clean earth to till. What weather they shall have is not ours to rule.” I didn’t quite fit this in anywhere above, but it’s a nice quote, kind and comforting. Except when you think of it for too long and realize that we’ve messed things up enough now that the weather, uh, is kind of ours to rule now only in the sense that we’ve made it so bad and its just always a hundred degrees now and oh my god WHAT HAVE WE—

- It was interesting to me that Denethor appeared so frequently in Gandalf’s sales pitch at the meeting of the captains. This works to re-emphasize the works thematic beats. But I also do wonder if it’s meant to indicate that Denethor is, simply put, still very much on Gandalf’s mind. Gandalf is very good at talking people away from despair, presenting them the choice and allowing them to make the hopeful one. Denethor not only rejected Gandalf’s philosophy, he did so bluntly and brutally. We never delve all that far into the deeper folds of Gandalf’s psyche, but I do wonder if it did a bit of a number on him.

- Speaking of Denethor—it continues to be a fun thought experiment to imagine how much more difficult the dude would have made everything for the last two chapters. You want a last debate? Denethor would have given you a last debate.

- I thought that Legolas’s comment about Tolkien at Pelagir to be intriguing: “In that hour I looked on Aragorn and thought how great and terrible a Lord he might have become in the strength of his will, had he taken the Ring to himself. Not for naught does Mordor fear him. But nobler is his spirit than the understanding of Sauron; for is he not of the children of Lúthien?” It’s another nice parallel / contrast between Aragorn and Sauron.

- Imrahil has always felt like an odd character to me. He feels very… illustrious, like a high medieval courtly knight in a story where those are in short supply. So when he calls Aragorn his liege lord and says that “his wish is to me a command” like some kind of Disney Prince, I was a half-way through a powerful, extended eye roll. But then my boy Imrahil steps in to be the voice of reason and reminds everyone that some heed should be given to prudence that that it’d be a shame to survive their maniac run at the Black Gate only to turn around and find the whole country burned and ravaged. Sorry, Imrahil, you’re good. Do your thing.

- I’m not sure it’s intentional or meaningful, but I was struck by the fact that when Gimli and Legolas are discussing how they can spiff up Minas Tirith, Gimli phrases it as “when” Aragorn comes into his own. Legolas phrases it as “if.”

- Prose Prize: For a while they walked and talked, rejoicing for a brief space in the peace and rest under the morning high up in the windy circles of the City. Then when Merry became weary, they wen and sat upon the wall with the greensward of the Houses of Healing behind them; and away southward before them was the Anduin glittering in the sun, as it flowed away, out of the sight of even Legolas. In the context of this chapter’s hope and uncertainty this has that that sense of a kind of lovely moment frozen in time before everything changes. You know the sort—if this made it into the film version it would have been shot during the golden hour.

- Contemporary to this Chapter: Frodo and Sam walk, and keep walking. My poor little dudes.

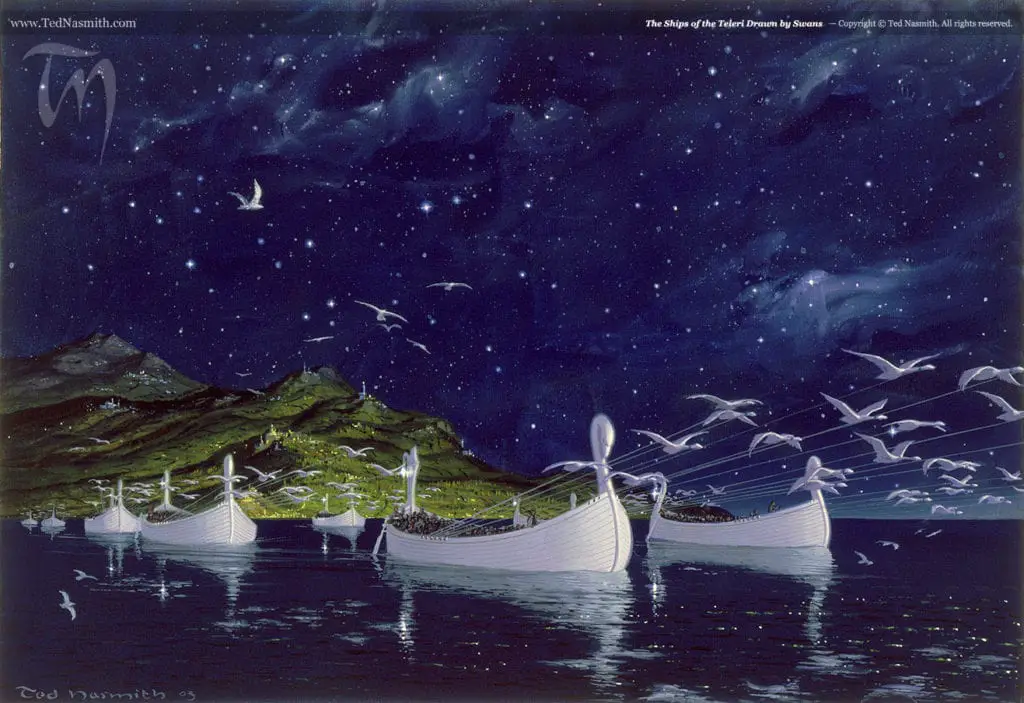

Art Credits: The film still is from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), courtesy of New Line Cinema. All other images, in order of appearance, are courtesy of Lorenzo Daniele, Ted Nasmith, aegeri, and, introducing, the “Beleriand” article on The One Wiki to Rule them All.